Column: For a man long afflicted with an illness made riskier by COVID-19, hope for the holidays

Evie Junior has been living with the pain and limitations of sickle cell disease for almost all of his 27 years.

He’s been hospitalized too many times to count with infections, exhaustion and excruciating pain, spawned by the incurable illness embedded in his genes.

“You try and adjust to the demands of the disease, but it’s never clear when the attacks are going to occur,” Junior explained. “You start to make progress on something, then you get sick and it takes you out, and you have to start over at square one.

“It’s one step forward and three steps back all the time.”

But the Anaheim man has good reason to feel thankful this holiday season: An experimental gene therapy being tested on him shows promise in disarming the debilitating disease.

Junior’s doctors at the UCLA Broad Stem Cell Research Center say the genetically modified stem cell infusion that he received last summer seems on track to correct the genetic error responsible for his sickle cell disorder.

“If we can get enough of the stem cells to pick up our [new] gene … the idea is he won’t have sickle cell anymore,” explained Dr. Donald Kohn, a UCLA professor and physician who has been studying gene therapy for 35 years and leads the medical trial, along with Dr. Gary Schiller.

So far Junior’s body has responded well enough that doctors are “pretty confident” the trial will help alleviate his suffering — and may light the way for new treatments of other incurable diseases, Kohn said.

For the doctors, that’s an “earthshaking” medical prospect. For Junior, it’s a sign that a life of promise — perpetually stalled by illness — may finally shift into high gear.

“I feel like something big is coming out of this,” Junior told me last week, as he prepared for a holiday celebration with his girlfriend.

“I want to be cured of this disease,” he said. “And I wish the world was more understanding about the people who are struggling with it.”

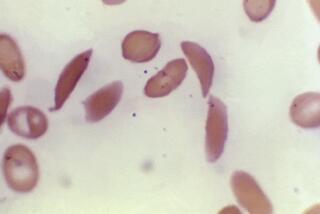

Sickle cell disease is the most common inherited blood disorder in the United States. It results from a mutation on a single hemoglobin gene, which causes red blood cells to take on a rigid sickle shape that clogs blood vessels and starves bones, brains and other organs of the blood they need.

Its trademark symptom is prolonged episodes of pain so severe “that on a scale of 1 to 10, it’s off the charts,” Kohn said.

Patients are also prone to premature strokes, heart disease, kidney failure and cognitive decline. The median lifespan for Californians with the disease is only 36 years.

And while the vast majority of those with the disease are Black Americans, 5% of the people suffering from sickle cell in California are Latino.

Research into the disease has ramped up in recent years, and new medications to help manage symptoms are available.

But the only way to disable the disorder is a bone marrow transplant, and that comes with considerable risks and complications. And fewer than 1 in 10 sickle cell patients end up finding a suitable donor.

That’s what makes this new route to a cure so exciting — and the process so calculatedly slow.

“These trials going on now are under very tight supervision and scrutiny,” said Schiller, co-leader of the UCLA trial, which began in 2015.

“Because we are introducing a new gene into the patient’s own cells, they are unlikely to be rejected and [will] stay for the life of the patient. So we have to make sure we are not creating some kind of genetic monster,” Schiller added.

The trial is funded by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the stem cell agency created by voters in 2004 and infused with $5.5 billion in new research money by voters who narrowly approved Proposition 14 this fall.

The initial trial attempt failed because the corrective gene didn’t make its way into enough of the patient’s stem cells. Still, it had value, Kohn said. “We learned where we were on the map. We were in the middle of the ocean. Now we’re on dry land.”

They hope to add a new patient to the trial every three months, Schiller said. Unlike other blood-related illnesses, “this is a disease we understood very well, but we could not fix it.”

Prospective trial subjects face long odds of being selected. “We have to choose people who have had a lot of symptoms, but their organs are not so damaged” they’re beyond recovery, Schiller explained. That’s not easy with a disease as destructive as sickle cell.

“We’re inundated with requests from people who will do anything to get past the disease,” said Schiller.

Junior was one of those people, desperate for a way to live a productive life.

As a child, he grew accustomed to frequent hospital stays. But the disease got progressively worse as he moved through his teens; the bone pain was so disabling, he often had to be sedated with heavy-duty opioids.

Still, he tried not to let the illness rule his life. “I always found ways to stay active,” he recalled. But the capricious nature of the disease made that hard.

He played high school football growing up in New York City, even when workouts left him struggling to breathe. But a long stint in the hospital the summer before his senior year spurred the coach to drop him from the team. He still feels bitter about that.

A few years later, he moved to Portland, Ore., and enrolled in college. He was working and attending classes when his illness flared up and he had to drop out. “I couldn’t keep up the pace,” he said.

And when COVID-19 worsened in the spring, Junior had to leave a job he loved — he was an emergency medical technician — because his compromised immune system made the risk of getting sick too high.

“It was rough for me, realizing that I have to adjust my future to what the disease requires,” Junior said.

At one point, the bones in both his legs were so damaged by the disease, doctors thought he might not ever walk normally again. Junior battled back.

But when his doctors in Portland told him there was nothing more they could do, Junior began researching alternative treatments and clinical trials.

“There was one study in Boston and another in Los Angeles,” he said. “Los Angeles was closer,” so he and his girlfriend packed up and left for Southern California.

Before long, Junior was back in the hospital again, as a subject in the UCLA trial.

But this time, his treatment — a weeklong chemotherapy regimen that wiped out damaged cells and primed his bone marrow to accept genetically altered replacements — was a signal of progress, not a setback.

“So yeah, it was bad, but not as bad as the pain of sickle cell,” Junior told me.

In the four months since then, he’s had fewer painful episodes and his modified stem cells seem to be producing healthy red blood cells, a sign that the treatment is working.

As the study goes on, he will be tested monthly for years and monitored as long as he’s alive. But Junior is not waiting for the “all-clear” to reimagine his life.

“My goal is to be a firefighter, if my cardiovascular system is strong and I can still push myself,” he said.

“The doctors hope some of my organs go back to the way they used to be. That some of the damage that’s been done will be healed.”

Junior admits he’s not quite clear on the medical aspects of all the procedures the doctors have put him through. But he’s grateful for the hope their research is delivering to people with sickle cell disease.

“From my understanding, the sickle cell gene is still there,” he said. “They didn’t correct it; it’s like there’s a crack and they put tape over it … so my cells are less sticky and will be able to function more effectively.”

And that, for now, is good enough for him.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.