Northern Ireland’s peacemakers of old urge an end to today’s political impasse

BELFAST, Northern Ireland — Former U.S. Sen. George Mitchell, an architect of Northern Ireland’s historic 1998 peace accord, urged the territory’s feuding politicians Monday to revive their mothballed power-sharing government, as a current political crisis clouded celebration of the peacemaking milestone.

Mitchell told a conference held to mark a quarter-century since the Good Friday Agreement that Northern Ireland’s leaders must “act with courage and vision as their predecessors did 25 years ago,” when bitter enemies forged an unlikely peace.

Mitchell, who chaired two arduous years of negotiations that led to the accord, joined former President Clinton and political leaders from Britain, Ireland and Northern Ireland to celebrate a moment when, Mitchell said, “history opened itself to hope” and three decades of sectarian bloodshed largely ended.

“The people of Northern Ireland continue to wrestle with their doubts, their differences, their disagreements,” said Mitchell, who is now 89 and being treated for leukemia. But he added: “The people of Northern Ireland don’t want to return to violence — not now and not ever.”

“The war is over,” agreed Gerry Adams, the former leader of Sinn Fein, the party linked during the conflict to the Irish Republican Army, which killed around 1,800 people. “The conflict’s finished.”

Northern Ireland wants to move forward. But 25 years after the Good Friday accord celebrated by Clinton and Biden, many are mired in a painful past.

The Good Friday Agreement has been held up around the world as proof that bitter enemies can make peace. It committed armed groups to stop fighting and set up a Northern Ireland legislature and government with power shared among unionist and nationalist parties.

Northern Ireland has changed dramatically since then — and some wonder whether the accord that created peace is still capable of sustaining it.

A young peacetime generation is increasingly shedding the rival identities — British unionist and Irish nationalist — that erupted into three decades of bloodshed that killed 3,600 people. But at the same time, Northern Ireland is locked in a political crisis that threatens to rattle the peace secured by the Good Friday Agreement.

“You’ve got a transformed society in which ‘unionist’ [or] ‘nationalist’ for many young people doesn’t mean anything,” said Katy Hayward, professor of political sociology at Queen’s University Belfast, the host of the three-day conference.

“But on the other hand, society is in a state of quite severe disrepair. We haven’t had a functioning Assembly for four out of the last six years, and our public services are crumbling around our ears.”

Britain and the European Union finally reach a post-Brexit agreement that will allow goods to flow freely to Northern Ireland from the rest of the U.K.

While peace has largely held, politics is deadlocked. Northern Ireland’s 1.9 million people have been without a functioning government since the main unionist party walked out more than a year ago to protest post-Brexit trade rules that, like so much in Northern Ireland, roiled notions of history and identity.

Participants at the conference — gently or pointedly — urged the Democratic Unionist Party, or DUP, to return to the power-sharing government. Its leader, Jeffrey Donaldson, was one of the few senior Northern Ireland politicians not mingling amid the university’s leafy quadrangles and red-brick buildings.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Queen’s University’s chancellor, urged people in Northern Ireland to show the same “unstoppable grit and resolve” that secured the peace deal.

“You have always found a way through, and I believe you will again,” she told delegates.

The Irish nationalist party Sinn Fein has won the largest number of seats in the Northern Ireland Assembly for the first time. With the victory comes the post of first minister.

Sinn Fein’s Adams predicted that the political impasse “will be resolved” by the DUP returning to government.

“As ministers they have a mandate to do that,” he told the Associated Press. “We can disagree on all of these other matters, but we should do it on the basis of the political and institutional office that we are entitled to on behalf of the people who elected us.”

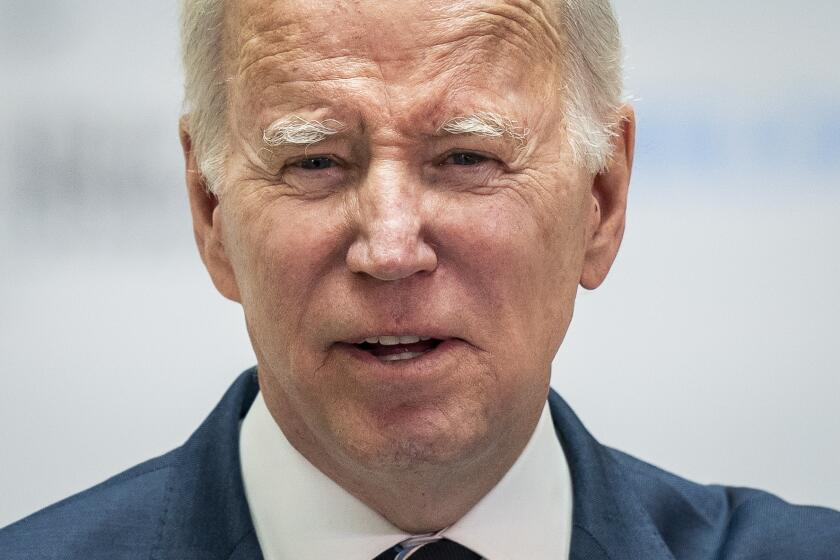

The three-day gathering caps commemorations of the April 10, 1998, peace accord that included a flying visit last week by President Biden, who was on his way to explore his Irish roots in the neighboring Republic of Ireland. During speeches in Belfast and Dublin, Biden reminded Northern Ireland’s politicians how strongly the U.S. remains invested in peace.

On a visit to Belfast, President Biden urged Northern Ireland to seize the economic opportunities of peace, saying the progress is ‘just beginning.’

“I wanted to make clear there’s a lot at stake,” Biden told reporters as he left Ireland on Friday. “And I think the combination of Ireland, the whole island, Great Britain, Northern Ireland, United States can change the way things occur.”

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who is due to host a gala commemorative dinner in Belfast on Wednesday, hailed “the courage, imagination and perseverance” of the peacemakers, including those, like former Northern Ireland Secretary Mo Mowlam, who have since died.

But critics say the British government has been, at best, careless with Northern Ireland’s peace — especially by leading Britain out of the European Union following a 2016 referendum.

Brexit shook the peace settlement by creating friction between Britain, the EU — including member state Ireland — and the U.S. It also destabilized the delicate political balance in Northern Ireland by reviving the need for a customs border between the EU and now ex-member Britain. An open border between Northern Ireland and EU member Ireland is one of the foundations of peace, so checks were imposed instead on goods moving from mainland Britain to Northern Ireland.

That unsettled unionists, who see the economic barrier as undermining Northern Ireland’s place in the United Kingdom. The Democratic Unionist Party walked out of the government in protest more than a year ago, collapsing it. The party has not returned, despite a deal reached by the U.K. and the EU in February to remove many of the border checks.

Increasing numbers of people argue that power-sharing must be tweaked to reflect the growing importance of forces such as the Alliance Party, which defines itself as neither unionist nor nationalist.

Meanwhile, violence hasn’t disappeared completely. In February, IRA dissidents opposed to the peace process shot and wounded a senior police officer.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.