BELFAST, Northern Ireland — By now, these walls were meant to have fallen.

Just as they did at the height of the Troubles — three blood-soaked decades of sectarian and political violence that shook Northern Ireland and transfixed a watching world — separation barriers still snake their way between neighborhoods of low-slung red-brick row houses, keeping mainly Roman Catholic Irish nationalists and Protestants loyal to the British crown physically separated from one another.

Nearly 50 feet tall in some spots, daubed with slogans and topped by metal spikes, the dividing lines are known, with scarcely a trace of irony, as “peace walls.” In the quarter-century since the Good Friday agreement, the landmark deal that largely ended the conflict, successive target dates for dismantling the barriers have slipped past, one after another.

“Ah no, love — they won’t come down in my lifetime, I don’t think,” said Kathleen Smyth, 63, walking with her daughter and granddaughter on Falls Road, the main thoroughfare in west Belfast, where the tricolor of the neighboring Irish Republic flutters from flagpoles.

Across the divide on Shankill Road, where many tattered storefronts display the Union Jack, 35-year-old maintenance worker William Harveson angled his chin in the direction of a sturdy gate that would seal off foot and car traffic through the barrier in a few hours, at sunset.

“It’s still needed,” he said. “Just in case.”

Cautionary notes like these have been a recurring theme amid commemorations of the anniversary of the agreement, signed on April 10, Good Friday, of 1998.

With some 3,600 people killed and many more maimed in the 30 years leading up to the accord, it is hailed as a vital lifesaving intervention. The pact, meant to keep balance between unionists who want to stay in the United Kingdom and nationalists who want to be part of the Republic, is also seen as a singular success story in U.S.-brokered conflict resolution.

Northern Ireland is a small place — fewer than 2 million people — but over the course of the Troubles, the sheer numbers of deaths and disappearances, imprisonment and injuries, left few families across the six counties untouched.

“Scaled up, it’s like your Civil War,” said Peter McLoughlin, a politics lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast.

In a major development that could signal an end to one of the world’s oldest conflicts, the Irish Republican Army announced Wednesday a “complete cessation” of violence in its struggle to end British control over Northern Ireland.

The milestone anniversary, though, has called attention to ongoing rancor that caused the power-sharing government — the deal’s centerpiece — to founder more than a year ago.

Commemoration organizers had hoped a political rapprochement would have happened by now, rather than casting a pall over ongoing anniversary events. This week, many of the agreement’s architects, former President Clinton among them, are gathering in Belfast, along with leaders and dignitaries including Britain’s King Charles III.

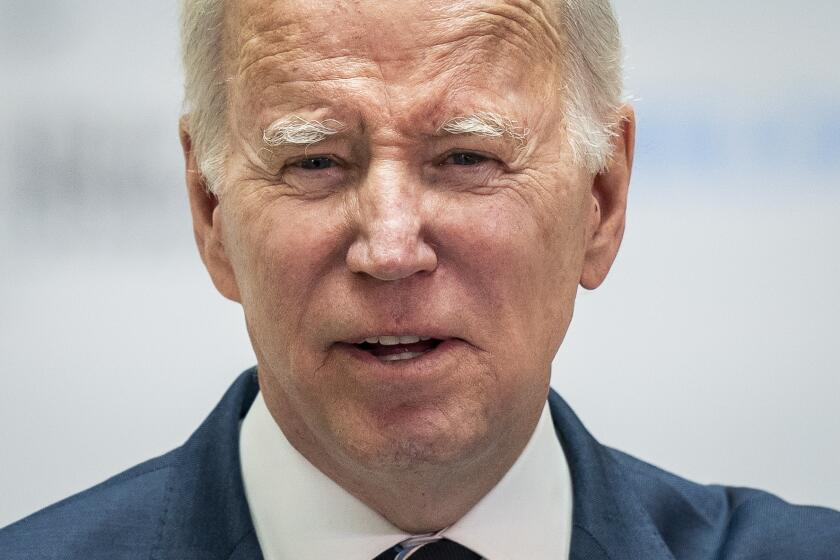

President Biden, in a speech in Belfast last week, hailed the accord’s achievements, but warned that hard work lay ahead to prevent a relapse into violence.

On a visit to Belfast, President Biden urged Northern Ireland to seize the economic opportunities of peace, saying the progress is ‘just beginning.’

“Northern Ireland will not go back,” he declared, dangling the prospect of greater economic incentives if rival politicians can once again join together in a functioning government.

With the Troubles on the cusp of living memory and beginning a passage into history, some observers point to a fundamental disconnect: the starkly different stories that people tell themselves and each other about the years of violence.

“There’s no consensus, really, on what took place and what it all meant,” said Sandra Peake, who heads Northern Ireland’s largest support network for Troubles victims and survivors. “So it can be hard to see a common way forward.”

::

‘Paying the price for everyone’s peace’

More than anything, Fiona Kelly fears coming face to face with her father’s convicted killer, who lives in her same small town. Under a prisoner release mandated by the Good Friday accord, he was freed after two years.

It’s been 30 years since Gerry Dalrymple was gunned down, but Kelly, 50, said she thinks every day of “Daddy,” a carpenter with a quiet sense of humor and a wide circle of friends among Protestants and fellow Catholics. He had no affiliation with any armed group.

Johnnie Proctor also lives in the same community as a man imprisoned for killing his father, a reservist in what was then the overwhelmingly Protestant police force, in 1981. He was 1 day old when his 25-year-old father, also named John, was shot dead as he left the hospital after visiting his wife and newborn son.

The assailant, eventually sentenced to a life term, served less than three years.

“I’ve probably seen him and spoken to him without even knowing,” said Proctor, now 41, who sells and services farm machinery. “But I put it aside — I don’t want to be thinking of who looks like him, who could be him.”

Besides the loss of their fathers, Kelly and Proctor share another bond: Both sat for large-scale portraits by the internationally acclaimed painter Colin Davidson of people who suffered grievous loss — bereavement, injury, disappearance of a loved one — in the Troubles.

The 18 works, collectively titled “Silent Testimony,” are on display this month at Stormont, the seat of the now-suspended Northern Ireland Assembly. Monumental yet intimate, each portrait measures about 4 feet by 4 feet, and is tightly focused on the subject’s face. Viewers tend to linger long before them.

Davidson, whose subjects have included musicians, actors and the late Queen Elizabeth II, and who once gave painting lessons to Brad Pitt, said the Good Friday agreement left him with the piercing sense that those who had suffered the most had somehow been left behind.

Brexit-related border worries grow as Northern Ireland, part of Britain, marks centennial of its creation

“I realized that this massive section of the community was paying the price of everyone else’s peace,” said the 54-year-old artist, who lives outside Belfast.

Davidson’s subjects sat for their portraits nearly a decade ago and met one another when the exhibition, which has toured extensively, originally opened in Belfast.

Four of the sitters have since died, but the survivors are friendly with one another; some have become extremely close. They reunited this month for the opening at Stormont.

Throughout the conflict, acts of violence were committed by all sides — nationalists, loyalists and state forces. But Davidson made the deliberate decision not to refer to the religion or political affiliation of anyone involved, whether victim or perpetrator, in short texts accompanying the portraits.

Instead, seeking to impart a common humanity, he recounted the circumstances of loss in the simplest terms: names, places, dates, a detail or two. He insists the paintings always be displayed together.

Davidson found his subjects by working with a trauma center called WAVE, which has provided material and mental-health support to thousands of people coping with the Troubles’ aftermath. He and its specialists found subjects of different faiths and from different walks of life, from inside and outside Northern Ireland.

Each portrait is emotionally wrenching, each in its own way. Paul Reilly, whose 20-year-old daughter Joanne was killed in a 1989 bombing, asked to sit for Davidson’s sketch in her bedroom, which he had preserved exactly as it was when she died, with a clock whose hands he set to the moment of her death.

If war is hell, there’s a credible case Bakhmut is its ninth circle, as Russia besieges the Ukrainian city that has symbolic, if not strategic, value for both sides.

Margaret Yeaman, whose facial injuries from a 1982 bombing left her blind, always wore dark glasses, but removed them for her sitting so Davidson could depict her eyes, which critics consider one of the most striking aspects of his portraiture. She, of course, was never able to see the haunting likeness that resulted.

Kelly said thinking of her children’s future helped her arrive at the conviction that the Good Friday agreement, for all its sorrowful legacy, is for the good of the country. She doesn’t flinch from painful memories of her father’s killing, though, because “forgetting would be a kind of death.”

Proctor said he carries the enduring lesson that religion and political backgrounds shrink into insignificance in the face of grief.

“One side or the other, none of that matters,” he said. “We all understand each other.”

::

‘It all seemed normal. But of course it wasn’t’

Martin Mulholland well remembers the surreal sight: He was looking, impossibly, from his hotel concierge desk straight onto the main stage of Belfast’s Opera House.

It was May 1993, and a thunderous blast set off by the Provisional Irish Republican Army had knocked a gaping hole in the masonry dividing the opulent music venue from the hotel where he’s worked for four decades. A Belfast landmark, the Europa Hotel claims the dubious distinction of being hit 33 times by bombs — including one that struck even before its doors opened in 1971.

In the well-practiced sotto voce of a veteran concierge, Mulholland offered an addendum: Only five of the explosions that damaged the building, he said, were from incendiary devices planted inside the hotel itself.

Miraculously, none of the attacks on the hotel resulted in fatalities. It was probably such a high-profile target, Mulholland said, because it was a symbol of investment, English-owned, and was home away from home to dozens of international journalists, so any strike in the vicinity was guaranteed to garner attention.

“Somehow you got used to it — it all seemed normal,” said Mulholland, whose 58 years have been bisected by the Troubles and the post-Good Friday era. “But of course it wasn’t, not in any way.”

::

‘It’s like they’re talking about World War I’

In Belfast’s central core, the rattle of gunfire and the heavy tread of British military vehicles has long been replaced by coffeehouse chatter, art-house buzz and the din of construction.

Where customers were once searched when entering the tiniest of shops, now teens, pensioners and young parents pushing strollers freely wander the walkways of a huge semi-enclosed shopping mall. The urban perimeter of Belfast’s downtown — a forbidding network of barbed wire, concrete and 12-foot fences — has long since vanished.

The bustling exterior, however, belies a society still profoundly wounded, said Siobhan O’Neill, a professor of mental health sciences at Ulster University.

Compared with the rest of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland suffers from significantly higher rates of suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction — which O’Neill and other researchers consider a legacy of years of strife, reverberating a generation later.

“For many people the conflict is still very real, part of their everyday lives,” said O’Neill, who studies trans-generational trauma. “Those who suffered continue to do so.”

The country’s young, especially those from the most economically deprived areas, remain vulnerable to the long-term effects of the violence, at home and in the society at large, experts say. But they also have a greater tendency than their elders to look to the future rather than the past.

Lars Jackson, a 15-year-old with a shock of acid-green-dyed hair, a leopard-print jacket and multiple piercings, does not identify as either Protestant or Catholic. Most of Lars’ friends don’t either, the teen said.

“That’s not like something we even talk about,” Lars said.

The Good Friday agreement, signed a decade before Lars’ birth, seems like ancient history — and all that preceded it even more so.

“I heard family stories, yeah — my grandparents’ house was bombed,” Lars said. “But really, if people talk about the Troubles and that, to me, it’s like they’re talking about World War I.”

::

The future, and the Brexit wild card

If the past is prologue, what does the future look like?

The uneasy sense of unfinished business stemming from the Good Friday agreement extends far beyond the current parliamentary deadlock, a recent flare-up of political violence, or complications surrounding Brexit, the U.K.’s exit from the European Union.

Northern Ireland was created as a Protestant-majority enclave, but that power dynamic is undergoing a dramatic shift.

The Irish nationalist party Sinn Fein has won the largest number of seats in the Northern Ireland Assembly for the first time. With the victory comes the post of first minister.

In the latest census, Catholics for the first time outnumbered Protestants, becoming a plurality but not a majority. And in elections last year, Sinn Fein became the first nationalist party to win the most seats in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

“Demographics will certainly continue to trend in a way that the nationalist population grows more than that of the unionists,” said Robert Savage, an author and history professor at Boston College. “Unification is a subject that will come up,” he said, but most analysts do not foresee a referendum any time soon on whether the six counties stay in the U.K. or join with the Republic of Ireland.

Under the Good Friday agreement, Northern Ireland’s secretary of state would be required to call a “border poll” if it appeared likely that a majority would vote to leave the U.K.

“Not in the next five years, I think,” McLoughlin, the Queen’s University lecturer, said of referendum prospects. But tensions involving Brexit could prove a wild card, he said.

Abortion pills: European doctor vows abortion bans or court rulings won’t stop her from getting medications to U.S. states including Texas, California.

For all its import, the Good Friday agreement may prove only one plot turn in a long narrative arc. History as drama is playing out, literally, in a production this month at Belfast’s historic Lyric Theater based on the final high-wire negotiations.

The Owen McCafferty play, titled “Agreement,” has been playing to a sold-out house. In a rave review, the Irish Times lauded it as a “compelling political thriller with echoes of Greek drama.”

“It’s a pleasant surprise, really,” said the theater’s artistic director, Jimmy Fay. Works related to the Troubles, he said ruefully, “aren’t always good box-office.”

Meanwhile, Northern Ireland may at last be decoupling itself, at least in the eyes of the outside world, from its long association with seemingly ceaseless conflict.

At the tourism office across from Belfast’s ornate City Hall, a couple from Australia debated how to pass the afternoon: one of the popular Troubles-themed taxi tours of murals and peace walls? Or the “Titanic Experience,” a sprawling interactive exhibit on the doomed ocean liner that famously set sail from the Belfast shipyards?

The Titanic, they finally decided. It’s a story with an ending everyone knows.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.