PORT GIBSON, Miss. — The bugs aren’t nearly as bad as you’d think. There are sweat flies, which are like little half-bees, half-mosquitoes without the sting or bite.

Woolly spiders drop down from the trees onto your neck and into your kayak when your head brushes against the leaves, so you quickly learn to avoid low-hanging branches. But when you’re moving at a clip in the open channel of the Mississippi River, they’re nowhere to be found.

A water moccasin may glide silently past, and a few times we’ve seen iridescent alligator eyes peering out at us before they sank back down into the depths. During dry spells, thousands of tiny frogs rush over the undulating caked-mud ripples that stretch across where the water has receded, and weird worms and winged roaches find the wetter highlands when the river’s swollen.

Once, we saw wandering trails of what we’re pretty sure were bobcat tracks between our tents when we woke up late and hungover, the mist already rising warm off the river’s shimmering surface.

But it’s never as scary as it sounds once you’re out there on the water, even one Friday night when four of us dropped two kayaks and a canoe into the blue, almost phosphorescent mini-waves after 10 p.m. and set up camp by moonlight five miles down.

Over four humid summers, these Mississippi jaunts became an annual ritual for our crew of longtime, 30-something friends. Life, jobs and circumstance had scattered us, but we all saved a week of vacation to reunite for what we came to simply call the river trip.

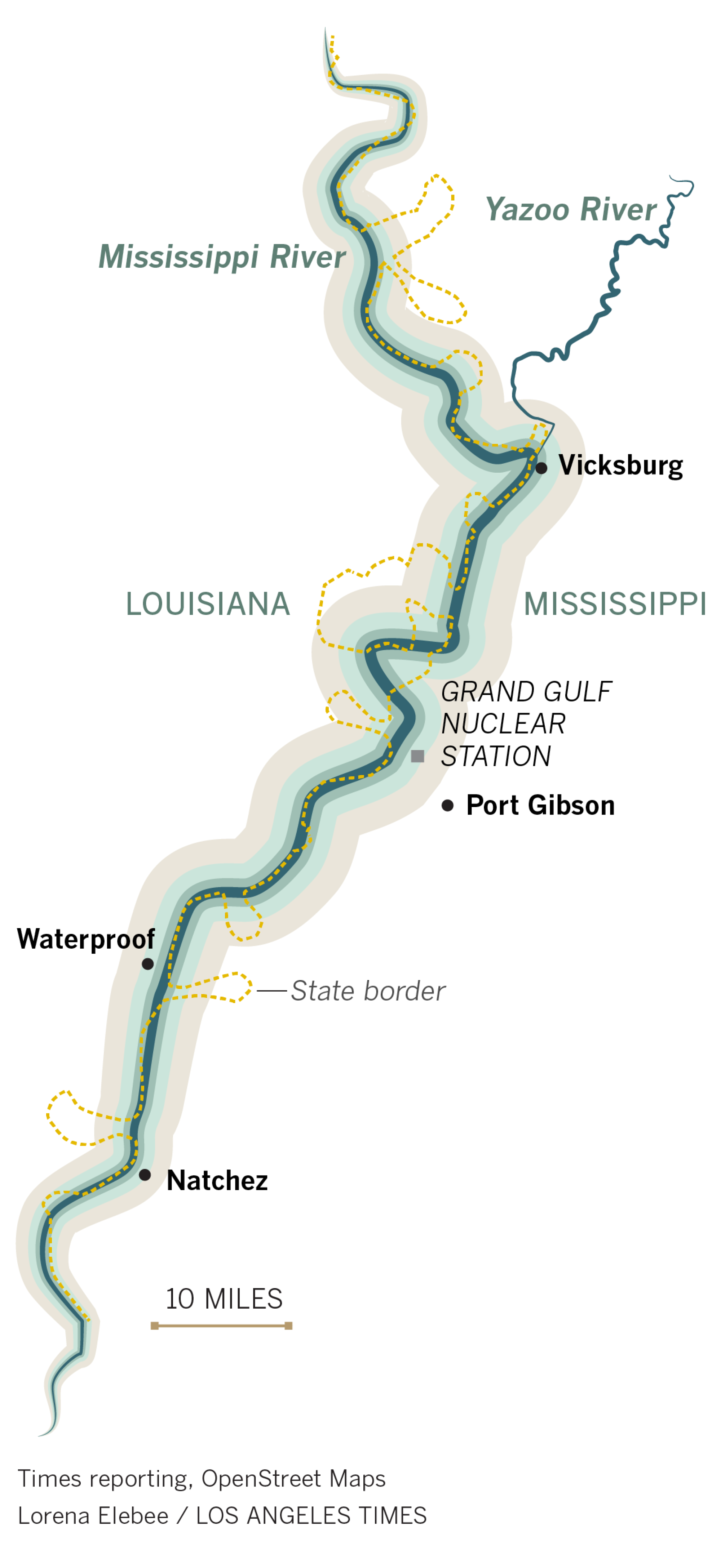

Each summer we floated a different segment of the river. In 2020, we made the 40-mile push from Port Gibson — a Mississippi hamlet Union military leaders deemed “too beautiful to burn,” according to an old wooden sign on the edge of town — to Natchez.

Under a threatening sky, we had set out in a canoe and kayak down this largely overlooked stretch the evening of July 6, 2020. The launching point was a cracked-cement boat ramp next to the Grand Gulf Nuclear Station, a towering power plant commissioned in July 1985, two months before I was born.

We were setting off yet again into wilderness and interstate shipping lanes on the smallest of craft. What we didn’t realize was that it would be the last consecutive annual trek we’d make.

These past two years grew too complicated to pull another trip together; we’ve moved across the country, had kids, spent hundreds of hours on Zoom. The COVID-19 pandemic dragged on.

We’ve had time to consider all that the trip had come to represent for us, a reminder of the simple power of friendship. What was once a lark had become a cherished rite, and in text messages and sporadic late-night calls, we’re dreaming of staging Act 5 this summer.

The river will be there, flowing ever southward.

::

After 30 minutes of paddling, your arms are burning, and you wonder how you got roped into this madness again. You’re way too out of shape to be out here, you tell yourself. What happens if at some point you simply can’t continue?

But after an hour or two the ache starts to subside, and then you’re cruising crisply through the air, which always feels magnitudes cooler when you’re paddling confidently through the calm, football fields away from land.

Sometimes, it’s necessary to cross the river, which at swell points can be a treacherous journey of more than a mile across whirlpools, eddies and rushing currents. But mostly the slipstream and your paddle carry you on.

One of the other guys always describes the stopping point as being a bend or two away, but five miles can look like a few hundred yards when you’re out on a straightaway and there’s nothing but rows of trees and beige-sand beaches for landmarks.

There are no pleasure boats on our stretches of the Mississippi — no party pontoons or families pulling wakeboarders behind rented powerboats. This is true social-distancing, along the ever-flowing jugular of American history, commerce and lore.

One time we helped dislodge a middle-aged couple after they crashed their little skiff into a line of rocks near our sandbar campsite. But aside from that ill-fated bateau and the occasional river patrol raft or fishing boat, the only vessels we’ve seen on these quiet, unappreciated miles from Vicksburg down past the tiny, ironically named town of Waterproof, La., and continuing south to Natchez, were tugboat-powered barges — one every hour or two, all day and night.

We continue riding for as long as we like, or the weather allows. In these near-tropic environs, the sky can darken or turn green and twist itself in an instant, then open up and dump cold rain down in ceaseless deluges. Sometimes storms seem to linger directly overhead, impervious to the wind’s whims, exploding every few seconds in thunderclaps and piercing, neon bolts.

Other times, like when Charlie — my friend from middle school who served three tours in Afghanistan and Iraq before moving to Texas to repair and ride motorcycles — kept needlessly pulling off to shore on the 2020 trek, the storms appeared to be headed straight for us, then whipped quickly by, leaving us dry in our hastily donned ponchos.

If a storm comes when we’re out on the water, we beach as quickly as we can and shelter under the dense leaf cover, which slows the rain at first, but eventually relents and lets it pour through. When we’ve already got camp set up, we huddle in our tents hoping we don’t get hit by lightning, and bask in the chilled air these tempests leave behind through dusk and into the night, a welcome reprieve from the punishing heat.

::

Before my now-wife and I moved from our tiny apartment in lower Manhattan to a two-bedroom Craftsman house in Birmingham in January 2015, I had never been to Alabama or Mississippi or any part of Louisiana north of Lake Pontchartrain.

I imagined needing a pickup to handle dirt roads and haul lumber, getting a big hound dog and taking up fly-fishing. Instead, I found a largely familiar modern existence, not so different in its daily rhythms from the one I had growing up in an old Maryland town.

Yet of course it was different in so many ways. And a couple of years later, I found in the remotest, deepest South a quintessentially American experience that changed all of our lives, but has in some respects changed very little since hand-carved wooden canoes and lashed-log rafts were among the most common vessels on the Mississippi.

On the river, the quiet can be deafening, and we can’t hear one another for hours at a time, as even a couple of hundred yards of distance on the river can stifle our loudest shouts. That visceral sense of departure, not just from the shore but from the daily toil, is what draws us back year after year.

It’s a feat of endurance, a treacherous tour of the wild South’s many dangers and nuisances, and an exhausting, sometimes monotonous gantlet. But it’s also a spiritual triumph, a self-guided tour of an untrammeled land, and a journey back in time.

Six of us have joined the crew at least once since 2017: Andrew, an earth scientist and paleontologist with a New England brogue who missed the trip for the first time in 2020 after moving from Vicksburg to Massachusetts; Thomas, a one-time professional riverman and Delta native who sticks to the canoe; Chris, a Scottish veteran of the Royal Navy-turned-journalist whom I met in a New York newsroom and now works as a reporter in Mobile.

Then there’s my younger brother, Brian, a longtime New Yorker who braved his first Mississippi trip in 2020 and moved to L.A. a couple of months before I did in 2021; Charlie, the hardy, curly-haired Texan; and me.

The wives and kids stay home, as they have no interest in joining us. The stink of our waterlogged river clothes, tales of lurking gators, snakes and spiders, and the 2-inch gash in my palm that I brought home in 2019 further solidified their conviction that they want no part of our adventures.

We load the boats up on the roof rack and tie them down with winching straps, stopping half a mile down the road to make sure they’re holding before heading on to the drop-off point. We leave one car there, pile into the truck, and drive upriver to where we’ll be putting in.

We manage the boats down to the water’s edge, weigh them down with our gear and supplies, slather ourselves in bug spray — and a fresh coat of sunscreen if it’s still light out — tuck a couple of Budweisers or bottles of water into the wells, and push off from shore.

Like when a highway clears and you get up to speed and immediately forget what it was like to be stuck in traffic, we’re quickly out on the water, the land shrinking away and the current carrying us ever farther toward New Orleans and beyond that, the sea.

::

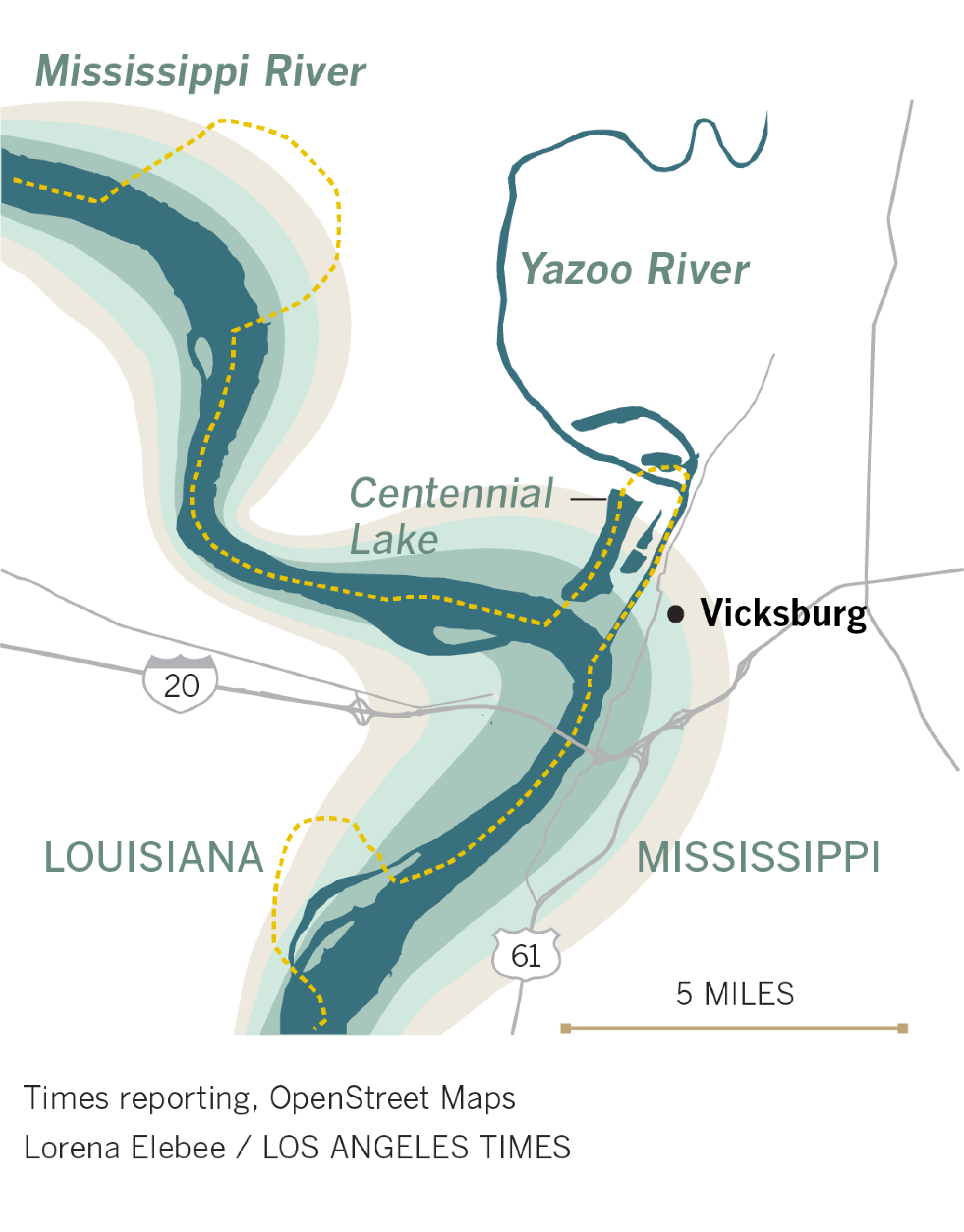

In 1876, Andrew told us at camp one night, the Mississippi jumped. Sediment had slowly filled the river’s main channel off the meander that had long flowed along Vicksburg’s downtown port, causing the water level to rise. One fateful day that late-Reconstruction spring, the differential between the main channel and the meander reached its apex, and the river suddenly shifted to its current route, leaving Vicksburg and its industry stranded next to a lake with no direct access to the vital artery.

It had been barely a dozen years since Vicksburg had come out of its months-long siege by Union troops, a period during which some of the town’s residents moved into hillside caves to avoid being shelled, and yet some still died from the concussive force of mortar explosions near their earthen tombs.

As of that fated day a century after America’s founding, Vicksburg was no longer situated along the banks of the country’s great waterway, which had for generations brought goods, people and wealth.

For 25 years after the Mississippi changed course, the Army Corps of Engineers worked to bring the Yazoo River to Vicksburg, which partially revived the town. But by that time rail was king, and the city never truly recovered.

Today, Vicksburg is a destination for faux steamboats and tour buses half-filled with aging Civil War buffs and gamblers drawn to its storied battleground and mildewed casinos.

Gunshots and sirens are commonplace as the sun goes down and well into the night on the crumbling blocks around Andrew’s old house, which served as home base for our river excursions before he moved north.

In a faded former gas station by the river, there’s a bar with brushed-metal shelves of canned goods and toilet paper, and taxidermied animal heads hanging from the walls. People still smoke in the dim light, and they serve beer by the bottle to a handful of regulars most nights. And now there’s a hip little brewery downtown that will make you short rib pozole or a plate of broccolini with cashew cream and a lemon vinaigrette.

::

You have to keep food simple on the river. Black coffee, overboiled eggs and toast charred on a wire contraption each morning; boiled potatoes and baked beans or spaghetti and Prego on the two-burner propane stove for dinner.

While one or two of us cook and finish making camp, the others gather logs and kindling and build the fire, which will sustain us deep into the night and keep animals away. Or so we hope. Thomas always has a loaded handgun in his pack — except in 2020, when Charlie took his place both in the canoe and as gunslinger.

The nights are spent drinking and fighting and laughing and devolving into previous versions of humans who spent their time in the dirt, foraging for wood, something to eat and connection. The only sounds are our own voices, the crackle of the fire, the purl of the river, the dull drone of the barges, and the constant chorus of bullfrogs, birds, bugs and coyotes.

We eventually retire to our tents, where we angle our phones above our heads, trying to get a bar of service to send a quick proof-of-life text home before we drift off.

The year of our last trip, COVID-19 dramatically reminded the world that nature has a way of imposing its will, reshaping life’s contours and forcing us to reconsider our priorities. Like the river when it changed course, we had no choice but to adapt as our lives took an unexpected turn.

It’s uncertain whether we’ll get back to the river this year, but the hope remains and our friendships endure. For now, we can reflect on those mornings on the river.

The dew is cool and damp against the skin when we wake up, and everything, even the air, is bathed periwinkle blue. We grab our soap and wade out into the river’s side channel for a wash-up and dip before breakfast, hoping a gar doesn’t rub up against our legs with its jagged teeth and prehistoric scales.

There’s always sand in the coffee and in the eggs, and there are never enough bowls or spoons or mugs. We pack everything back up in a much more haphazard way than we did at home.

Everything somehow always still fits in the boats and we push away one by one. We’re off again, the beach is the past and the river is the moment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.