ANTA, Peru — As antigovernment protests spread across the Peruvian highlands last month, Remo Candia Guevara, a 42-year-old community leader in this rural farming town, grew increasingly anguished.

National police had repeatedly shot into crowds of unarmed protesters, killing dozens. Candia blamed President Dina Boluarte.

“She’s an assassin,” Candia said in a video interview with a local journalist on Jan. 10. “Many young people have died, cut down by her bullets.”

The next day, Candia and thousands of others marched through the streets of Cusco, a nearby city known for its Inca ruins and narrow, colonial-era streets. As they clashed with police, gunfire erupted and Candia fell to the ground, bleeding from his stomach. He died at a hospital that night.

His death and others have further fueled the protests, which in recent days have spilled from the impoverished, largely Indigenous Andes to the cosmopolitan, coastal capital, Lima. With South America’s fifth-largest economy paralyzed by highway roadblocks, the country finds itself at an agonizing political impasse.

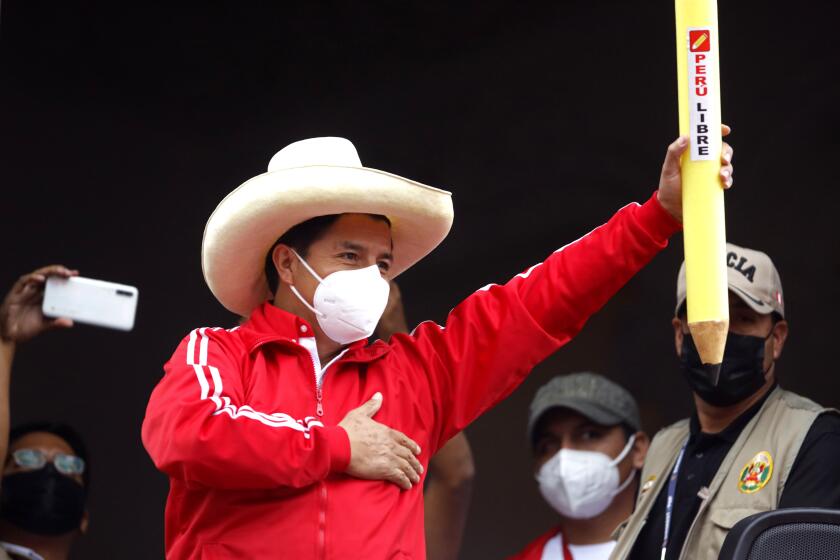

The demonstrations began in December after the arrest of then-President Pedro Castillo, whose campesino roots had inspired many poor Peruvians. Facing allegations of graft and fighting for his political survival, he had managed to fend off two impeachment attempts by right-wing lawmakers. But when he announced plans to dissolve Congress and install an emergency government, a move widely condemned as an attempted coup, even many allies turned against him. He was taken into custody and removed from office.

A former schoolteacher who champions the poor, Peru’s new president takes office amid deep divisions

He has never held elective office and was little known until a few months ago. Now Pedro Castillo must govern a divided nation.

Protesters demand that Boluarte, who was Castillo’s vice president, resign and that Congress schedule new elections this year.

She says she won’t step down — and has compared the protesters to terrorists. Congress has repeatedly refused her proposal to hold elections in October, voting against that idea again on Wednesday.

But as the body count rises, with 58 dead and more than 1,000 injured, the movement has morphed into a mass rebellion clamoring not just for a new government but broader political, economic and social change.

While democratic elections are held regularly in Peru, critics say that the results often have more to do with settling scores and politicians getting rich than installing effective governments.

“This is the product of years and years of accumulated indignation,” said Raúl Pacheco, an anthropologist at the National University of St. Anthony the Abbot in Cusco. “It’s about much more than an election.”

The roots of the widespread discontent are self-evident: Gaping inequality, entrenched corruption and a tumultuous political system that has seen three Congresses and six presidents rotate through power over the last five years.

Polls show Peruvians have the lowest level of satisfaction with democracy in Latin America. Former President Alberto Fujimori, the strongman who ruled in the 1990s, is in prison for graft and human rights violations. Five more former leaders, including Castillo, are being investigated on suspicion of corruption.

But there is another grievance at play, one especially present in the Andes, where many feel that the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire was just the beginning of a long history of racist subjection of Indigenous people.

The deaths of Candia and other protesters from the region have only deepened that view.

“They don’t see us as humans,” said his sister, Marilia Candia Guevara, 36. “Our lives aren’t worth as much as theirs.”

“We’ve always been fighting for our rights,” she added. “Of course we’re exhausted.”

“We can’t permit these racists to continue governing.”

— Mario Turpo Orozco, a leader in the Andean town of Urcos

Long before dawn broke on a recent damp morning, villagers throughout the Cusco region began heaving boulders, branches and old car tires onto the highways that connect the towns nestled high in the Andes with the rest of Peru.

Men and women, many wearing brightly embroidered traditional hats and skirts, would stand guard at these homemade blockades all day, stopping vehicles from passing.

“There isn’t any other strategy,” said Mario Turpo Orozco, a leader in the town of Urcos, where he and others had blocked a road leading to Lima. “We can’t permit these racists to continue governing.”

The blockades, which authorities say are underway in nearly half of the country’s provinces, have snarled trade and tourism.

The ancient Inca city of Machu Picchu, usually crowded with visitors, is closed indefinitely. The country’s biggest mines warn they may have to halt operations. Officials say Peru’s economy and infrastructure have taken a $1.3-billion hit and analysts warn that the country may be heading for recession.

Protesters say the economic distress makes their point.

Peru is highly dependent on the Andes region, with its rich mineral deposits, extensive agriculture and the archaeological jewels that draw 4 million tourists to the country annually. Yet the region and its people have long been neglected.

“We’ve been abandoned by the state,” said Turpo, 60, who said there are villages near his community that lack water and electricity. Schools are scant and of poor quality, he said. A promised hospital in Urcos never arrived.

The pandemic only highlighted the failures of the government, he said. So many people died in Urcos, villagers had to build a new cemetery. Peru had one of the highest COVID death rates in the world, with vaccines, oxygen and hospital beds in short supply.

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s election in Brazil is the latest triumph for the left, which now controls six of Latin America’s seven largest countries.

In 2021, a presidential candidate burst on the scene promising to change all of that.

A former teacher and union leader from a rural mountain town, Castillo campaigned in a farmer’s hat and promised “no more poor people in a rich country.”

His victory over Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of Peru’s imprisoned former autocrat, was heralded as a resounding rejection of the political establishment.

Castillo governed chaotically, filling posts with unqualified political allies and drawing allegations that his family members were profiting off official contracts. His supporters insist that he was the target of a witch hunt, with Congress launching a series of campaigns to remove him shortly after he was sworn in.

What angered them most were the insults lobbed at Castillo by the Lima elite. Rafael López Aliaga, the conservative mayor of the capital, called him a “donkey.” On TikTok, people made fun of his country accent. Wealthy Peruvians smashed piñatas of his likeness at birthday parties and weddings.

Javier Torres Seoane, the director of Noticias Ser, a news site focused on coverage of the southern Andes, said many identified with the discrimination Castillo faced.

“Despite the fact that it was a bad government for the people, people still consider him one of theirs,” Torres said.

In Mexico, a growing movement is challenging discrimination against darker-skinned people. Lighter-skinned Mexicans still dominate film, politics and business.

Remo Candia Guevara certainly did.

Like the former president, Candia was proud of his traditions. He wore capes sewn by his mother and participated in ritual dances that merged his family’s Catholic and Quechua traditions. An accountant and leader of a campesino association by day, he spent evenings and weekends working on a hillside plot in Anta where corn, wheat and quinoa grew.

Candia and his family were not Castillo fanatics, his sister said. “But when they attacked him it felt like an attack on all of us.”

So when police responded to protesters with bullets, Candia, a father of two who dreamed of bringing a playground to his community, joined the demonstrations.

After his funeral, which filled Anta’s central square with hundreds of mourners, roadblocks in the area multiplied. Anger at the president spread, with the words “Dina Asesina” appearing on the side of a mountain, spelled out in white rocks.

And a group of hundreds of protesters made its way to Lima, joining a wider migration of people from across the Andes who had brought their fight to the capital in hopes of finally being heard.

“There was so much dust and bullets. It was the most tragic moment of my life.”

— Helard Sonco Villanueva, student and protester

Helard Sonco Villanueva stepped off a bus in Lima on Jan. 19, a knapsack slung across his back.

He’d come from Juliaca, a southern city on a high mountain plateau near Lake Titicaca. Sonco, a 30-year-old engineering student, had been at a protest there when thousands of demonstrators tried to take over the city’s airport. Police opened fire, killing 18.

Sonco watched two of his university classmates die, as well as Marco Antonio Samillán Sanga, a medic who was shot while aiding a protester who had inhaled tear gas.

“There was so much dust and bullets,” Sonco said. “It was the most tragic moment of my life.”

He thought to himself: “If we don’t rise up now, we never will.”

In Lima, Sonco and protesters from other parts of the country sheltered for several days at the National University of Engineering. They moved elsewhere after police used a tank to break down the gate at a nearby public university and detained hundreds of protesters.

Human rights officials have roundly condemned the government’s response to the demonstrations.

“We have never seen anything as brutal as what we’re seeing now,” said Mar Pérez, a lawyer for the National Human Rights Coordinator, a nonprofit made up of 78 Peruvian rights groups. Security forces, she said, “are using weapons of war.”

With thousands of protesters massed in Lima, a dangerous daily ritual has begun.

Every afternoon, protesters from the mountain provinces gather downtown, sharing stew cooked in giant pots and chanting antigovernment slogans.

Vendors sell flags (“I love you Peru, that’s why I defend you”) and plastic glasses to protect against the tear gas that is to come.

Then the police arrive and the clashes begin.

Gladys Lucano, a 60-year-old farmer and grandmother, has been there for the last two weeks, facing off nightly with police.

“They call us terrorists,” Lucano said, noting that the word carries heavy connotations in a country that was menaced for years by the communist Shining Path guerrillas.

“But we are just citizens,” she said. “We don’t have anything to defend ourselves with. The real terrorist is the president.”

Lucano never expected to be in the middle of the biggest protest in Peru’s recent history. But after seeing so many men that looked like her sons killed by security forces, she felt compelled to join.

“Let them kill me,” she said as she walked into a scrum of protesters facing off with police. “I’m here for my kids, for my grandchildren, for the future of Peru.”

“How many more of us are going to die? Or will they eliminate all of us?”

— Marilia Candia Guevara, whose brother was fatally shot during a protest

Some Peruvians, particularly those in the capital, share the contention of Boluarte and right-wing lawmakers that the protesters are to blame for the violence. New elections, they say, will only deepen the political chaos.

But a poll this week shows that most of the country now backs the protesters’ demands.

The Institute of Peruvian Studies survey found that 74% of the country believes Boluarte should resign, 89% disapprove of Congress and 73% want new elections this year. Significantly, support for the government has dipped even in Lima.

There is a growing sense that Boluarte, whose only government experience before becoming vice president was at a regional office of an agency that issues identity documents, is in over her head.

And although few here believe that her resignation will solve everything, many agree that it is a needed first step. “Early elections won’t end all of our problems,” said Pérez, the human rights lawyer. “But at least we could have a moment to breathe.”

Back in the town of Anta, Candia’s family has agonized over the political situation while also mourning their loss.

“How many more of us are going to die?” his sister asked. “Or will they eliminate all of us?”

She was sitting with her mother in the family’s dimly lighted adobe home.

In the corner, flowers and candles decorated an altar that they had made to Candia featuring a photo of him posing proudly in traditional dress, his red vest decorated with images of birds and flowers.

Marilia said her only wish is that her brother’s death ends up meaning something — that it is a part of a bigger story of change.

Despite everything, she said she felt something like hope.

Special correspondent Adriana León in Lima contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.