A former schoolteacher who champions the poor, Peru’s new president takes office amid deep divisions

LIMA — It was one of the most improbable electoral victories in recent Latin American political history.

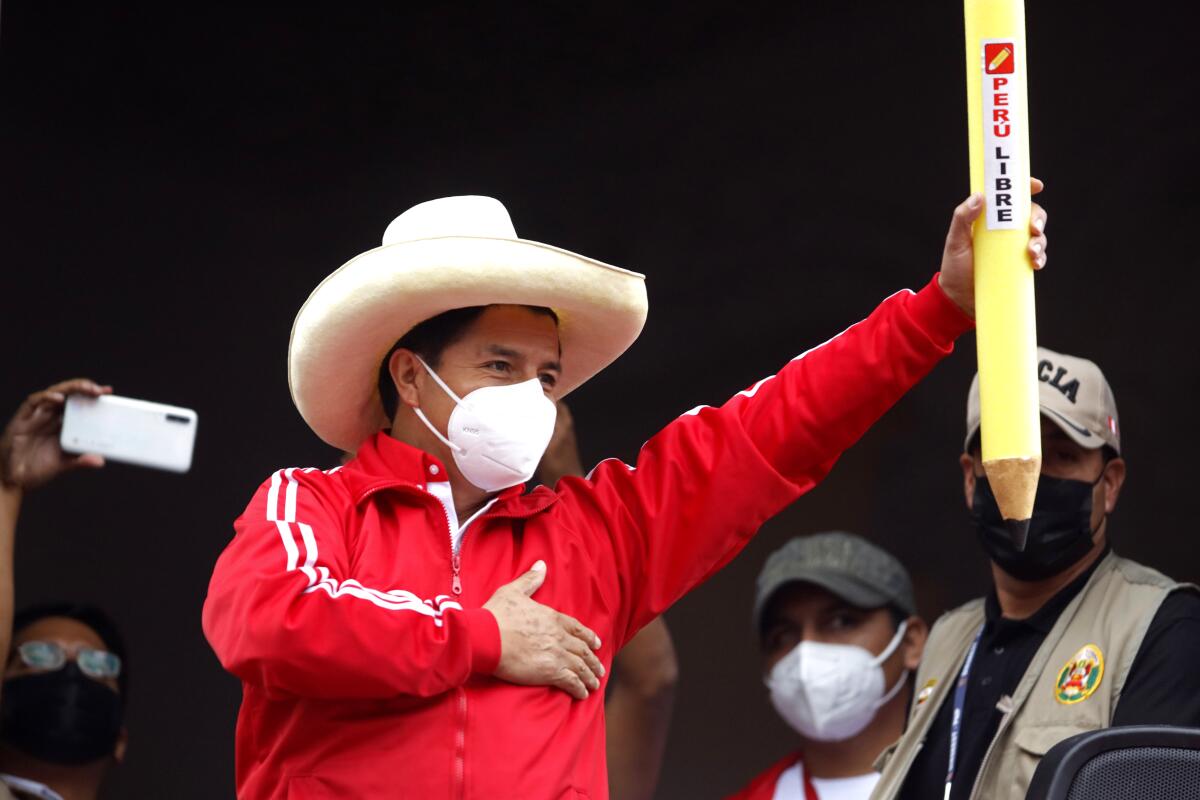

Pedro Castillo, a 51-year-old former rural elementary school teacher who has never held office, won the presidency of Peru in a race so close and so disputed that it took election authorities six weeks to confirm the results.

Now the left-wing populist who ran on the slogan, “No more poor in a rich country,” faces a daunting task: Uniting a deeply polarized nation of 32 million that has been ravaged by COVID-19. Castillo is set to be sworn in as president on Wednesday, the 200th anniversary of the country’s independence.

His grandiose promises of achieving social equality have brought hope to the dispossessed but unnerved the business community, foreign investors and Peru’s powerful military.

“The fact remains that the establishment is very anti-Castillo,” said Jo-Marie Burt, a professor of political science and Latin American studies at George Mason University in Virginia. “He’s come to power promising very big things — to create a more just and more inclusive society.”

His vanquished opponent, Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of disgraced former President Alberto Fujimori, has already made clear that she intends to undermine Castillo’s authority.

After weeks of alleging without evidence that she was a victim of widespread voter fraud, she begrudgingly conceded defeat last week. But she also labeled the official vote tallies “illegitimate” and promised protests “in defense of democracy,” stoking doubt about Castillo’s ability to govern or even complete his five-year term.

Her highly disciplined Popular Force party in Congress has already been instrumental in the ouster of two Peruvian presidents.

Just how Castillo plans to transform society remains unclear. He has been short on details, and the Free Peru party — which sponsored his candidacy even though he is not a member — holds just 37 of the 130 seats in a divided Congress. Fujimori’s right-wing bloc has 24 seats.

During the campaign, Castillo accused multinationals of “plundering” the wealth of the world’s second-largest copper producer and vowed to raise taxes and royalties on Peru’s crucial mining sector and rewrite the constitution to give more economic leverage to the government.

But in recent months Castillo has toned down his populist rhetoric, seeking to cast himself as a moderate pragmatist welcoming to business. He vowed to protect private property and individual savings.

“He’s a guy who did not at all expect to be president, so the level of improvisation is really high,” Burt said. “He’s trying to navigate a lot of turbulent waters.”

Some of that turbulence is already emanating from within the fractious Peruvian left.

“More than with the opposition, the first big problem that Castillo has is with his own internal front, with these forces and pressures from inside the party,” José Carlos Requena, a political analyst, told Peru’s RPP Noticias, the country’s major radio outlet.

An especially polarizing figure is Vladimir Cerrón, an avowed Marxist and former governor of Junín province who founded and heads the Free Peru party — and who invited Castillo to assume the candidacy of his party.

In public comments, Cerrón has insisted that Castillo must toe the party line on contentious issues like reforming the constitution. On Monday evening, Free Peru faithful were dispatched to the president-elect’s home in Lima and chanted, “If Castillo makes a mistake, the party will straighten him out!”

Castillo has rejected suggestions that he will be a puppet for Cerrón, who is serving a suspended four-year sentence for misappropriation of public funds.

But Cerrón has been throwing his weight around. It was Cerrón this week who hosted ex-Bolivian President Evo Morales — an icon of the Latin American left in town for Castillo’s inauguration — at a trendy restaurant in Lima’s upscale coastal Miraflores district.

Castillo will also probably face pressure from the United States to back Washington’s efforts to oust leftist governments in Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

On Monday, U.S. Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken spoke with Castillo and expressed hope that Peru would play a “constructive role in addressing the deteriorating situations in Cuba and Nicaragua,” according to the State Department.

It’s not clear that Peru’s new leader will go along. Following this month’s protests in Cuba, Castillo used Twitter to denounce the decades-long U.S. embargo on the island as “anti-human and immoral.”

At the same time, Castillo has denied allegations from Fujimori and her allies that he would take Peru down the path of communism.

“We reject anything that goes against democracy and we reject any idea of copying another country’s model,” he told ecstatic supporters last week from a balcony of his Free Peru party headquarters in Lima. “We will create true economic development, guaranteeing legal and economic stability.”

Until a few months ago, Castillo was little known outside of his home zone of Cajamarca, in Peru’s northern Andes, one of its poorest regions, despite a wealth of mineral riches.

But in April elections, he and Fujimori emerged from a fragmented field of 18 candidates as the two finalists. That led to a June 6 runoff.

It pitted the ex-teacher with his signature straw peasant’s hat against one of Peru’s most polarizing figures. Fujimori, a former congresswoman who had already lost two races for the presidency, is facing trial on charges of corruption involving millions of dollars in allegedly illegal contributions to previous campaigns. Prosecutors have recommended a 30-year prison sentence and labeled her party a “criminal organization.” Her father is serving a 25-year prison term for human rights violations and other crimes.

Her insistence that she had been cheated out of the election drew comparisons to former President Trump’s unsubstantiated charges of electoral fraud in last year’s U.S. election.

After six weeks of tense uncertainty, featuring almost daily street protests, Peru’s electoral board last week declared Castillo the winner. He won 50.12% of the ballots cast compared with 49.88% for Fujimori — a difference of just 44,000 votes.

His electoral strength was in the rural highlands, with a large Indigenous and peasant presence, where in some cases he captured as much as 80% or more of the vote. Fujimori won in the capital and other coastal areas that have benefited from the export-oriented, free-market policies that she has championed.

A decade ago, Peru was among the fastest-growing economies in Latin America, as poverty rates declined and the middle class expanded amid a boom in metals and other commodities.

The economy was already slowing down when the pandemic hit. Peru has the world’s highest per capita COVID-19 death rate. Its economy contracted 11.1% last year, according to the World Bank, throwing some 2 million people into poverty and setting the stage for this year’s electoral upheaval.

Times staff writer McDonnell reported from Lima and Mexico City and special correspondent León from Lima. Special correspondents Cecilia Sánchez in Mexico City and Andrés D’Alessandro in Buenos Aires contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.