Charges, communism, COVID-19 and a controversial name in Peruvian politics define an election

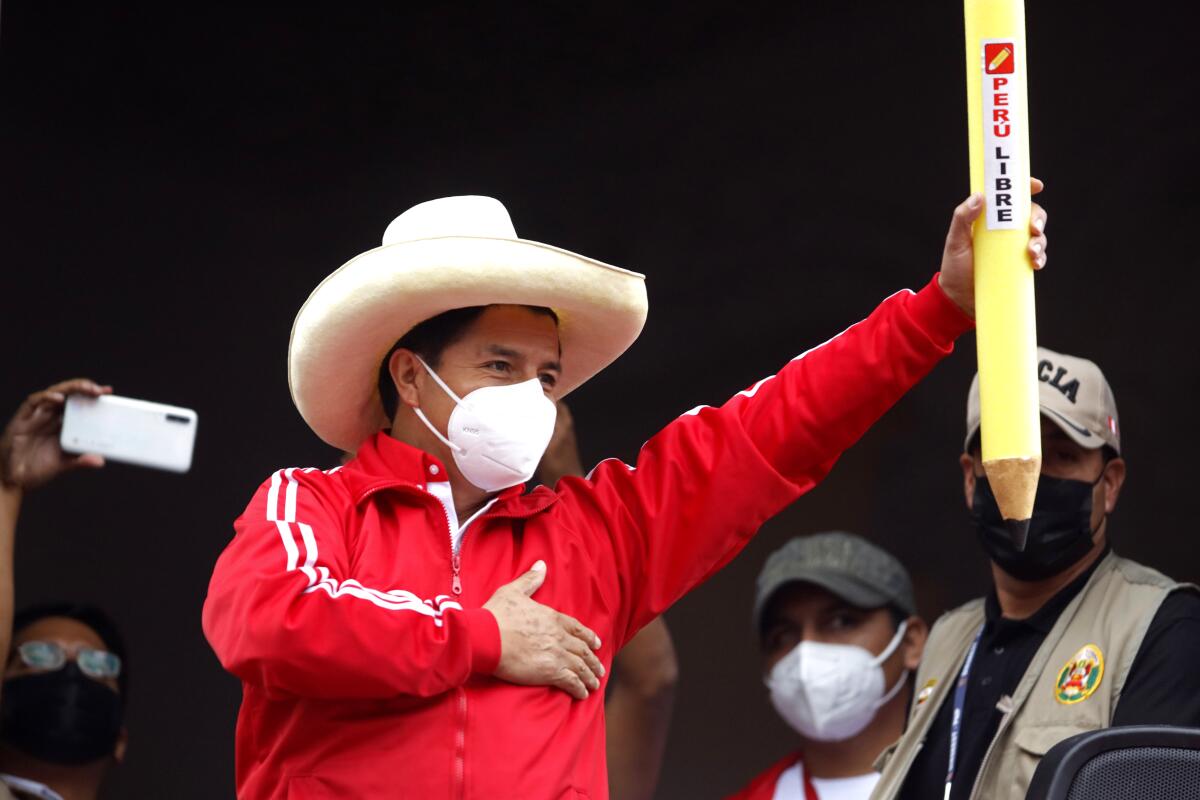

CUZCO, Peru — The country folk came to cheer their presidential candidate — Pedro Castillo, a teacher-turned-left-wing-populist lauded by supporters as a savior in hard times.

“We want a man of the people, a campesino, a president for us all,” said Maria Pinto, 45, a homemaker at a raucous pro-Castillo rally in this historic mountain town. “Pedro will return the country’s wealth to the people.”

His opponent fails to generate similar excitement. Keiko Fujimori, a two-time loser in presidential races and the daughter of Alberto Fujimori, the former president serving a 25-year prison sentence for crimes against humanity, stands accused of taking bribes and laundering money.

But supporters, especially in the business class, battered during the pandemic, view her as a safer choice.

“With COVID-19, tourism died, we were all thrown out of work, and we now need stability to come back,” said Victor Hugo Quispe, who runs a tour company here and plans to cast his vote for Fujimori. “This is not a time for more uncertainty.”

The election Sunday featuring a pair of candidates from opposite ends of the ideological spectrum comes as many Peruvians are losing hope for their economy and their democracy.

Six of the last seven presidents have either been forced from office amid allegations of wrongdoing or have faced charges upon completing their terms. The country had three different presidents in a week last November amid fierce street demonstrations against the dysfunctional political class.

COVID-19 brought a different kind of misery, hobbling the healthcare system, killing at least 184,000 of Peru’s 32 million people — the highest death rate in the world — and shrinking the once-robust economy by 11.1 % last year. The World Bank estimates that 2 million people were driven into poverty.

“So much of what we are seeing in this election comes down to the devastation of COVID-19,” said Gustavo Gorriti, a well-known Peruvian journalist. “There was so much loss, so much suffering, both on a personal level and to the economy.”

Polls show a near draw as Fujimori cuts into the lead that Castillo held following his first-place finish in an initial round of balloting in April. She finished second. Each garnered fewer than 20% of the votes in a fragmented field of 18 candidates.

The contest has bared some of the geographic, socioeconomic and ethnic factors that divide the country.

Castillo, 51, who has never held public office and was a political unknown before this year, draws much of his support from the poor, Indigenous population in the Andes. Fujimori, 46, who would become the country’s first female president, runs stronger in the capital, Lima, and other coastal areas that have benefited from the longstanding export-oriented, free-market economic policies she has championed.

A sense of uncertainty and foreboding precedes election day, as each campaign portrays the opposing candidate as an extremist — Castillo a communist and a terrorist who would scare off investors, Fujimori a thief and dictator-in-waiting.

Adding to the tension was the massacre of 16 people last month in a remote jungle region known for illicit cultivation of coca, the raw ingredient of cocaine.

The assailants left leaflets warning people not to vote June 6 and denouncing Fujimori supporters as “traitors.” Authorities attributed the strike to remnants of the Maoist Shining Path guerrilla group, which waged a bloody insurgency against the government in the 1980s.

After Alberto Fujimori became president in 1990 — a milestone for the tiny minority of Peruvians who trace their ancestry to Japanese immigrants — he made his reputation as a no-holds-barred foe of the insurgents. At one point, he dissolved Congress while alleging that legislators were blocking his efforts to fight terrorism and institute free-market economic reforms to tame hyper-inflation.

His style of rule became known as fujimorismo — assailed by critics as authoritarianism, but hailed by his daughter’s backers as robust leadership.

“Fujimori lifted Peru out of the economic crisis and at the same time defeated terrorism,” said Carmen María Carranza, 38, a marketing executive for a beauty-products firm. “Those who didn’t live through those years don’t even know. But I saw how my parents suffered. … God save us from communism.”

In 2009 — nine years after he resigned and Congress found that he was “morally unfit” to serve — Fujimori was convicted of ordering a military squad to carry out a pair of massacres that left 25 dead while he was in office.

The unabashed champion of her 82-year-old father’s checkered legacy, Keiko Fujimori has vowed to pardon him if elected.

She was just 19 when her parents separated in 1994 and her father made her first lady. After studying business administration in the United States, she was elected to the Peruvian Congress in 2006, proceeding to lose presidential runs in 2011 and 2016.

In March, after a two-year investigation, prosecutors charged her and associates with money laundering and corruption, most notably alleging that she received $1.2 million in bribes from Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht for her 2011 campaign.

Prosecutors called for the dissolution of her party, Popular Force, and recommended she be imprisoned for 30 years. A judge is reviewing the evidence.

Fujimori denies the charges and calls them a political hit job. She spent 13 months in detention on related charges in 2018 and 2019.

Being elected — with attendant presidential immunity — could keep Fujimori out of jail.

For his part, Castillo has vowed to eliminate corruption, a rallying cry for his base.

“Pedro is for the people, Keiko is a criminal!” chanted Julián Rojas, 40, a taxi driver who attended a Castillo rally recently in Lima’s central Plaza San Martín, where he helped hoist up an effigy of Keiko Fujimori in a mock jail cell and parade it around the square.

Castillo, who dons a wide-brimmed peasant hat and plays up his rural roots, has said that he would rewrite the constitution to give more economic power to the government.

That would include raising taxes and royalties on Peru’s crucial mining sector. He has accused multinationals of “plundering” the country’s wealth of copper and other minerals.

His motto — “No more poor in a rich country” — has resonated in the countryside and among the urban working class and fueled a torrent of criticism that he would turn Peru into the “next Venezuela.”

Castillo has vowed that he would protect private property and individual savings, and rejects any ideological affinity with Hugo Chavez, the late socialist leader whom critics hold responsible for economic ruin in Venezuela.

“We aren’t communists, we aren’t chavistas, we aren’t terrorists,” he told a crowd in April in the northern Peruvian city of Máncora. “We are workers, just like any of you.”

For her part, Fujimori has endeavored to soften her right-wing image, vowing to implement measures to help the poor — including raising the minimum wage, bolstering aid for students and pensioners, and providing “oxygen bonus” grants of about $2,500 to each family that lost somebody to COVID-19.

She also recently conceded that she and her party had committed “errors” and vowed to run a clean government.

Among Fujimori’s improbable supporters are Mario Vargas Llosa, the Peruvian Nobel laureate who lost the 1990 presidential election to her father and has been a scathing critic of both father and daughter. In a column for the Spanish daily El País, Vargas Llosa, a resident of Madrid, labeled Castillo a threat to democracy and called Keiko Fujimori “the lesser of two evils.”

Nonetheless, many have questioned her commitment to democracy, given her father’s history and what critics call her hostility to criticism and free speech.

“I would never vote for the return of fujimorismo,” wrote columnist Ernesto de la Jara in La República newspaper. “To vote for her would be to betray myself.”

For many, there may be no good choice at the polls. Voting is mandatory for most, but it’s unclear how much the pandemic will dampen turnout — or how many voters may file spoiled or blank ballots in rejection of both candidates.

“Both Fujimori and Castillo and their parties have a lot of support, and both have unleashed a lot of passion, but both have also been discredited and rejected for many reasons,” said Eduardo Dargent, a political scientist in Lima. “For many voters, especially in the middle classes, this election presents a difficult, even tragic moment.”

Special correspondent Adriana León in Lima contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.