TAIPEI, Taiwan — On Tuesday nights, BX2AN sits near the Xindian River, motionless but for his thumb and middle finger, rhythmically tapping against two small metal paddles. They emit a sound each time his hand makes contact — from the right, a dit, or dot; from the left, a dah, or dash, the building blocks of the Morse code alphabet.

For the record:

11:58 a.m. Oct. 28, 2022A prior version of this story stated incorrectly that “the higher the frequency, the shorter the wavelength, and the farther signals can travel.” It has been corrected as follows: “Such shortwave radio signals are able to traverse great distances by bouncing off particles in the Earth’s atmosphere.”

“Is anyone there?” he taps.

The replies come back in fits and starts: from Japan, then Greece, then Bulgaria. Each time, BX2AN, as he is known on the radio waves, jots down a series of numbers and letters: call signs, names, dates, locations. Then he adjusts a black round knob on his transceiver box, its screens glowing yellow in the dark.

There can be no doubt that this is his setup. That unique call sign is stamped across the front of his black radio set, scrawled in faded Sharpie on his travel mug and engraved in a plaque on his car dashboard. On the edge of his notepad, he’s absent-mindedly doodled it again, BX2AN.

In the corporeal world he is Lee Jiann-shing, a 71-year-old retired bakery owner, husband, father of five, grandfather of eight and a ham radio enthusiast for 30 years. Every week, he is the first to arrive at this regular meeting for Taipei’s amateur radio hobbyists.

They gather on a small, grassy campground on the city’s southern border, where Lee hunches over his radio from the back of his van, listening to the airwaves as the sun goes down. He doesn’t talk much; he prefers the dits and dahs to communicate. By 8:30 p.m. he has corresponded with six other operators in various countries.

U-R-N-A-M-E, Lee asks a contact in Bulgaria. G-E-K, the operator replies, adding a location, S-O-F-I-A. Lee taps out L-E-E, and his city in response.

As more members of the Chinese Taipei Amateur Radio League, or CTARL, trickle in, two other operators are setting up stations several yards away. One of them, like Lee, starts tapping. The other prefers a handheld voice transmitter, tuning into some indistinct chatter across the Taiwan Strait.

In the age of smartphones and DMs, amateur radio has become a niche hobby in Taiwan. Participants like Lee, many of whom are older than 50, tinker with electronics, exchange postcards with new contacts and compete to see who connects with the most far-flung places.

But ham radio might turn out to be more than just a pleasant pastime.

The self-governing island, about 100 miles east of China, is weighing wartime scenarios in the face of growing military aggression from its vastly more powerful neighbor. If cell towers are down and internet cables have been cut, the ability of shortwave radio frequencies to transmit long-distance messages could become crucial for civilians and officials alike.

The recreational use of wireless radios, which transmit and receive messages via electromagnetic signals, became popular in the early 20th century, starting in the U.S. Since the federal government began issuing licenses in 1912, the number of noncommercial radio operators in the country has surpassed 846,000, according to the Federal Communications Commission.

Amateur radio operators (also known as “hams”) tend to use the high radio frequencies, a measure of the oscillation rate of electromagnetic waves. Such shortwave radio signals are able to traverse great distances by bouncing off particles in the Earth’s atmosphere. (Never heard of it? Ham radio still occasionally pops up in movies and TV — “A Quiet Place,” “The Walking Dead” — as a communication channel of last resort.)

The technology proved useful during World Wars I and II, when countries such as the U.S. and Britain limited civilian airwave activity but enlisted skilled hobbyists to help send and intercept covert messages. More recently, during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the BBC used shortwave radio to broadcast its news service after communication towers were attacked. Ham radio operators were also able to listen in and interrupt communications among Russian soldiers.

Taiwan was not an early adopter. Under the Kuomintang, or Nationalist Party — whose leaders fled to the island in 1949 after losing to Mao Zedong’s Communist Party in China’s civil war — civilian use of amateur radio was all but banned by a government that remained wary of mainland spies. The first licensing exams weren’t offered until 1984. But today, with the threat of cross-strait conflict making headlines, Taiwan has about 25,000 licensed amateur radio operators, according to the National Communications Commission.

For years, China has asserted that Taiwan is part of its territory, a position the U.S. has acknowledged but stopped short of endorsing. As Chinese President Xi Jinping has pushed his vision for unification — if not peacefully, then by force — President Biden has hardened his rhetoric on defending the island’s democracy, raising fears of an inevitable clash.

After U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited here in early August, the People’s Liberation Army in China launched missiles, planes and warships around Taiwan for several days. The growing military pressure has also highlighted the vulnerability of the island’s internet, which is heavily reliant on several major undersea data cables.

As Taiwan confronts the possibility of war, many civilians are making preparations of their own.

Shoichi Chou, 45, remembers using a wireless radio as a teenager to date and talk with his friends. But two years ago, watching Xi call more forcefully for unification, he decided to reacquaint himself with the technology in case war broke out and communication lines went down. Now a licensed operator, Chou, who lives in the city of Taoyuan, keeps a radio in his emergency bag, along with spare batteries, water and a hard hat.

“I feel like it’s incredibly important,” said Chou, the owner of a laptop customization studio. “If just a few bases don’t have electricity, you won’t have any way to use your phone.”

Kenny Huang, chief executive officer of the Taiwan Network Information Center, a nonprofit that serves local internet users, said several government ministries have begun working on contingency plans for any conflict-induced outages. “This year,” he said, “the government realized because the tension between Taiwan and China is getting worse, they have to prepare for the worst-case scenario.”

The use of ham radio is not yet officially part of that equation. But for T.H. Schee, a Taiwanese tech entrepreneur who hosts lectures on civil defense, the devices seem like a natural solution to his topmost concern: securing communication capabilities in the face of an attack.

“Ham radio has been proven to be [a] reliable communication channel in several world wars, and the Ukraine-Russia conflict as well,” Schee said. In Taiwan, amateur operators have helped train military personnel and assisted in emergency communications for events including deadly natural disasters and the annual New Year’s Eve festivities in downtown Taipei.

“Some people will think that with today’s technological advancements, this thing is being phased out,” said David Kao, secretary general of CTARL. “But ... new things are not always reliable.”

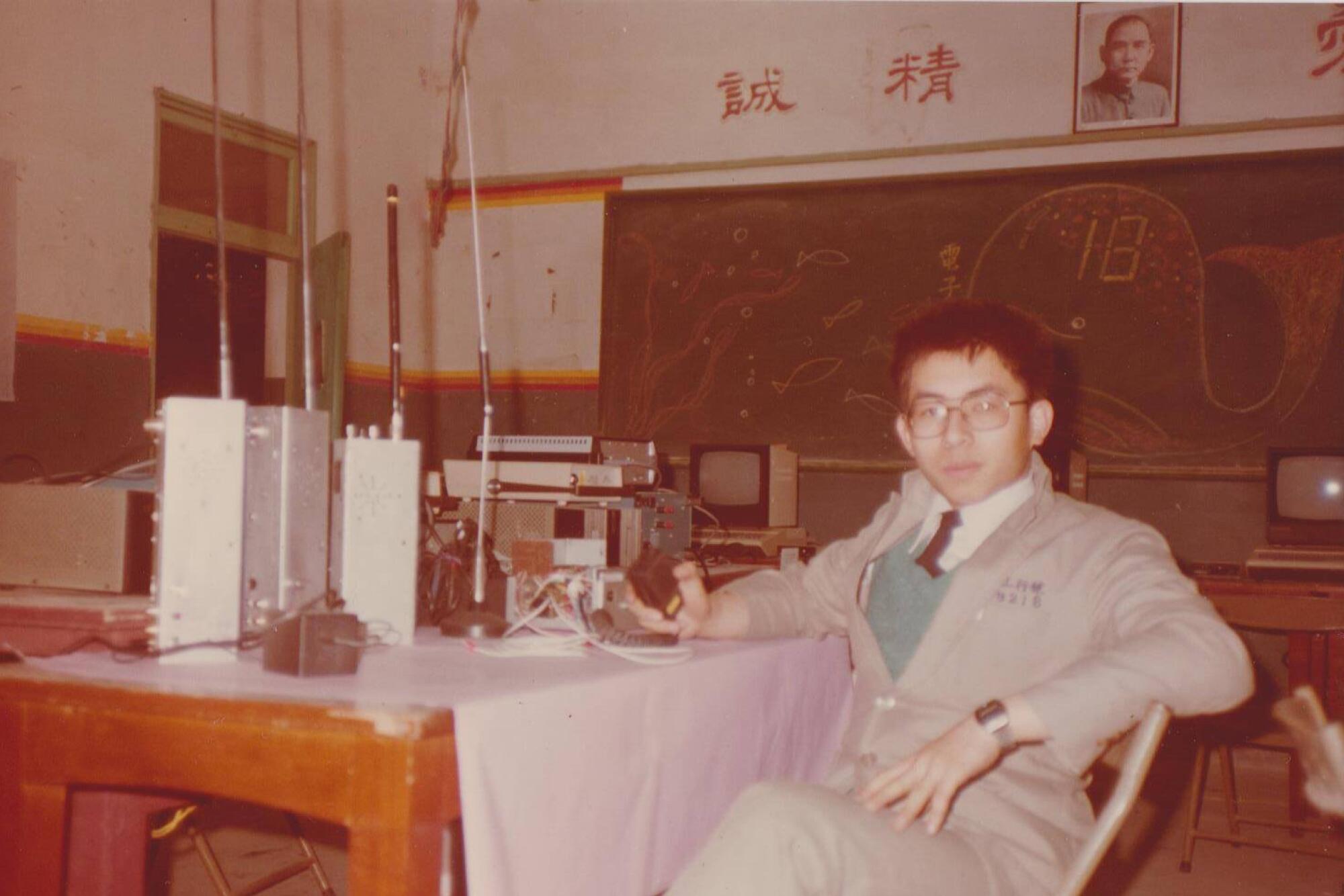

Kao was 9 when he first encountered a basic broadcast radio in 1981. Intrigued, he scoured the library for literature on the novel devices and went from stall to stall at a local market seeking more information. At that time, obtaining an amateur license was illegal under martial law imposed by the Nationalists, also known as KMT. But restrictions started easing a few years before martial law was lifted in 1987. Four years later, CTARL was founded, and Kao finally got his license.

Some hobbyists found their own ways around the rules. In 1981, when Wayne Lai was 16, he was so eager to play with radios that he built his own contraband out of electronic refuse.

His self-selected call sign back then was U0, or youling in Chinese, a homonym for the word “ghost.” His friends similarly styled themselves Apple, Snoopy, Frog, Mazda, Bandit, Chicken Leg, Spare Rib. A few years before Taiwan began to loosen restrictions, Lai and his friends were raided by the authorities. Their radios were confiscated, and they had to sign pledges to not use them again.

Today, amateur radio is very accessible, but Lai, one of the Tuesday night regulars at the campgrounds, worries that it doesn’t hold the same allure for people who grew up in the internet era.

“Look. Old guy,” Lai says, pointing at one of the operators who set up on a concrete bench. “Old guy. Old guy. Old guy. Old guy,” he continued, gesturing around a table. “There aren’t many young people coming to play anymore.”

Luo Yi-cheng is quick to challenge that pronouncement. The 27-year-old accounting specialist, who learned about ham radio from a YouTube video last year, compared it to discovering Facebook — a different way to connect with people around the world.

The hardest part, he said, was picking up the receiver and uttering his first words — it was something akin to speaking in front of the entire class in grade school. But the sense of accomplishment from a successful connection was greater than anything Luo had experienced using his smartphone. “I was completely unaware that this existed,” he said. “I think younger people aren’t simply disinterested; they probably just don’t know about this.”

For the most part, ham radio is a solitary activity. Nonetheless, there’s a festive atmosphere by the river. Lights strung up in a nearby tree illuminate screens and dials in the dark. Someone digs out a stack of ring toss hoops, while others fuss over small cups of tea.

Amid the sound of crickets and radio static, it’s common to hear hams chat about the weather, their latest devices and how to best hide their gadget addictions from their wives. Some of them band together to purchase new electronics via a group chat called “Buy, Buy, Buy.”

“With so many electronics, there’s no way you can use them all,” one member reasons.

“But when I see it, I still want to buy it,” another insists, to the commiserating laughter of the group.

Meanwhile, at the back of Lee’s van, another message arrives in halting beeps. He writes down the corresponding characters — E71A — before tapping out a response.

He waits but gets nothing.

In the radio silence, a colleague uses his phone to look up the call sign. “What is this flag?” he asks Lee, who is also at a loss. Upon closer inspection, the icon, a blue-and-yellow rectangle, is labeled “Bosnia and Herzegovina” in tiny letters.

Others gather behind them, looking over Lee’s shoulder. “Where is that?” they ask eagerly. “Did you respond?” “Did you make contact?”

“Didn’t go through,” Lee answers, his voice telegraphing dejection. “Hearing them, but not being able to reach them, is really depressing,” he said, tapping his fingers over his heart.

But all is not lost; there’s always the possibility of another exciting connection in the days ahead. Plus, it’s a peaceful night, and the threat of war — for now — seems as distant as the operators the hams are hoping to reach.

The night’s attendees pack up their equipment and return supplies to their cars. A few of them help pull the lights down from the tree, stowing them in Lee’s van for the next Tuesday gathering. And the regulars know Lee will probably be back at the river by the weekend, unable to stay away for long.

David Shen of The Times’ Taipei bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.