Marcos, sworn in as Philippine president, stays silent on his father’s abuses

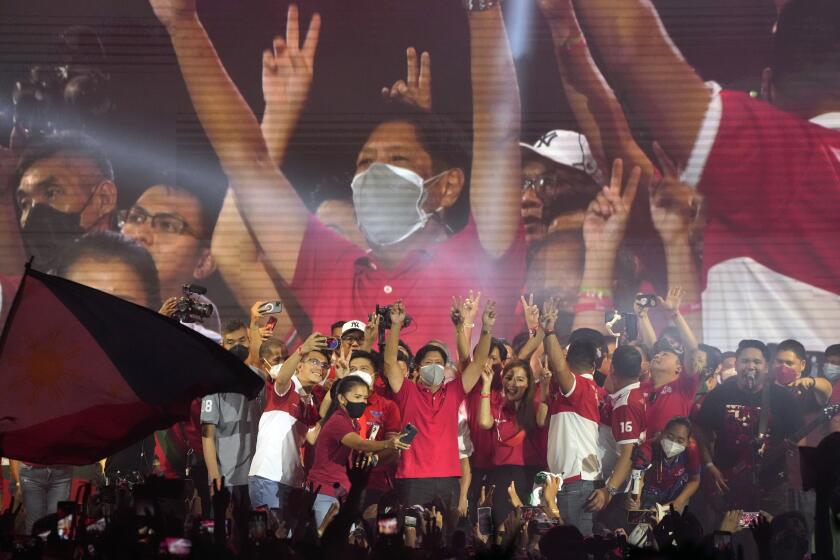

MANILA — Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the namesake son of the ousted dictator, praised his father’s legacy and glossed over its violent past as he was sworn in as Philippine president Thursday after a stunning election victory that opponents say was pulled off by whitewashing his family’s image.

His rise to power, 36 years after an army-backed “People Power” revolt booted his father from office and into global infamy, upends politics in the Asian democracy, where a public holiday, monuments and the Philippine Constitution stand as reminders of the end of Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s tyrannical rule.

But in his inaugural speech, Marcos Jr. defended the legacy of his late father, who he said accomplished many things that had not been done since the country’s independence.

“He got it done, sometimes with the needed support, sometimes without. So will it be with his son,” he said to applause from his supporters in the crowd. “You will get no excuses from me.”

“My father built more and better roads, produced more rice than all administrations before his,” Marcos said. He praised the infrastructure projects by his predecessor, Rodrigo Duterte, who ended his six-year term also with a legacy of violence, strongman rule and contempt for those who stood in his path.

The new president called for unity, saying that “we will go farther together than against each other.” He did not touch on the human rights atrocities and plunder that his father was accused of, saying he would not talk about the past but the future.

Ferdinand Marcos ruled the Philippines with an iron fist. Now a TikTok disinformation campaign is propelling his son toward the presidency.

Activists and survivors of the martial law era under his father protested Marcos’ inauguration, which took place at a noontime ceremony at the steps of the National Museum in Manila. Thousands of police officers, including anti-riot contingents, SWAT commandos and snipers, were deployed in the bayside tourist district for security.

Chinese Vice President Wang Qishan and U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris’ husband, Doug Emhoff, were among foreign dignitaries who attended the event, which featured a 21-gun salute, a military parade and air force jet fly-bys.

“Wow, is this really happening?” said Bonifacio Ilagan, a 70-year-old activist who was detained and severely tortured by counterinsurgency forces during the elder Marcos’ rule. “For victims of martial law like me, this is a nightmare.”

Marching in the streets, the protesters displayed placards that read, ”Never again to martial law” and “Reject Marcos-Duterte.”

The Philippines introduces an all-female coast guard radio unit as it challenges Chinese aggression in the South China Sea after years of inaction.

Such historical baggage and antagonism stand to hound Marcos during his six-year presidential term, which begins at a time of intense crises.

The Philippines has been among the countries worst-hit in Asia by the COVID-19 pandemic, after more than 60,000 deaths and extended lockdowns sent the economy into its worst recession since World War II and worsened poverty, unemployment and hunger. As the pandemic was easing early this year, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent global inflation soaring and sparked fears of food shortages.

Last week, Marcos announced that he would serve as secretary of agriculture temporarily after he takes office to prepare for possible food-supply emergencies.

He also inherits decades-old Muslim and communist insurgencies, crime, gaping inequality and political divisions inflamed by his election.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The Philippine Congress last month proclaimed his landslide victory, as well as that of his running mate, Sara Duterte, the daughter of the outgoing president, as vice president.

“I ask you all pray for me, wish me well. I want to do well because when the president does well, the country does well,” he said after his congressional proclamation.

Marcos received more than 31 million votes and Duterte more than 32 million of the more than 55 million votes cast in the May 9 election — massive victories that will provide them robust political capital as they face tremendous challenges as well as doubts arising from their fathers’ reputations. It was the first majority presidential victory in the Philippines in decades.

Outgoing President Duterte presided over a brutal anti-drugs campaign that left thousands of mostly poor suspects dead in an unprecedented scale of killings being investigated by the International Criminal Court as a possible crime against humanity. The probe was suspended in November, but the ICC chief prosecutor has asked that it be resumed immediately.

The Philippine government is hoping to boost its crucial tourism industry by lifting its pandemic-induced ban on foreign travelers.

Marcos and Sara Duterte have faced calls to help prosecute her father and cooperate with the international court.

Marcos, a former governor, congressman and senator, has refused to acknowledge the massive human rights abuses and corruption that marked his father’s reputation.

During the campaign, he and Duterte avoided controversial issues and focused on a vague call for national unity.

His father was toppled by a largely peaceful pro-democracy uprising in 1986, and died in 1989 while in exile in Hawaii without admitting any wrongdoing, including accusations that he, his family and cronies amassed an estimated $5 billion to $10 billion while in office.

Hard-won access to family planning has diminished during the pandemic, with a resulting surge in births expected to strain healthcare resources.

A Hawaii court later found him liable for human rights violations and awarded $2 billion to more than 9,000 Filipinos who filed a lawsuit against him for torture, incarceration, extrajudicial killings and disappearances.

Imelda Marcos, his widow, and her children were allowed to return to the Philippines in 1991 to engineer a stunning reversal of their political fortunes, helped by a well-funded social media campaign to rehabilitate the family name. Imelda, the 92-year-old family matriarch, sat in at the inauguration in a traditional light-blue Filipiniana dress, kissed her son and posed for pictures on the stage.

Marcos’ alliance with Duterte — whose father remains popular despite his human rights record — and his famous name helped him capture the presidency. Many Filipinos remain poor and grew disenchanted with post-Marcos Sr. administrations, Manila-based analyst Richard Heydarian said.

“These allowed the Marcoses to present themselves as the alternative,” Heydarian said. “An unregulated social media landscape allowed their disinformation network to rebrand the dark days of martial law as supposedly the golden age of the Philippines.”

Along metropolitan Manila’s main avenue, democracy shrines and monuments erected after Marcos Sr.’s 1986 downfall stand prominently. The anniversary of his ouster is celebrated each year as a special national holiday, and a presidential commission that has worked for decades to recover the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth still exists.

Marcos Jr. has not explained how he will deal with such stark reminders of the past.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.