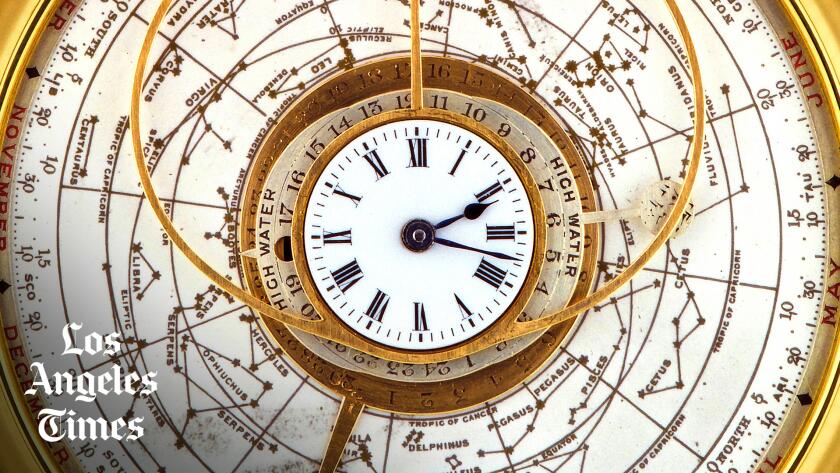

The double-sided pocket watch had a map of the heavens on one of its two dials, an intricate display whose complexity nodded to the mechanical masterpiece ticking within the solid-gold case.

It told time, of course, but it could also chart the sunrise and sunset, the phases of the moon, the path of constellations, the signs of the Zodiac, and track equinoxes, solstices and the declination of the sun.

The watch’s creation 112 years ago must have seemed like a bit of alchemy — and operating it a brush with magic.

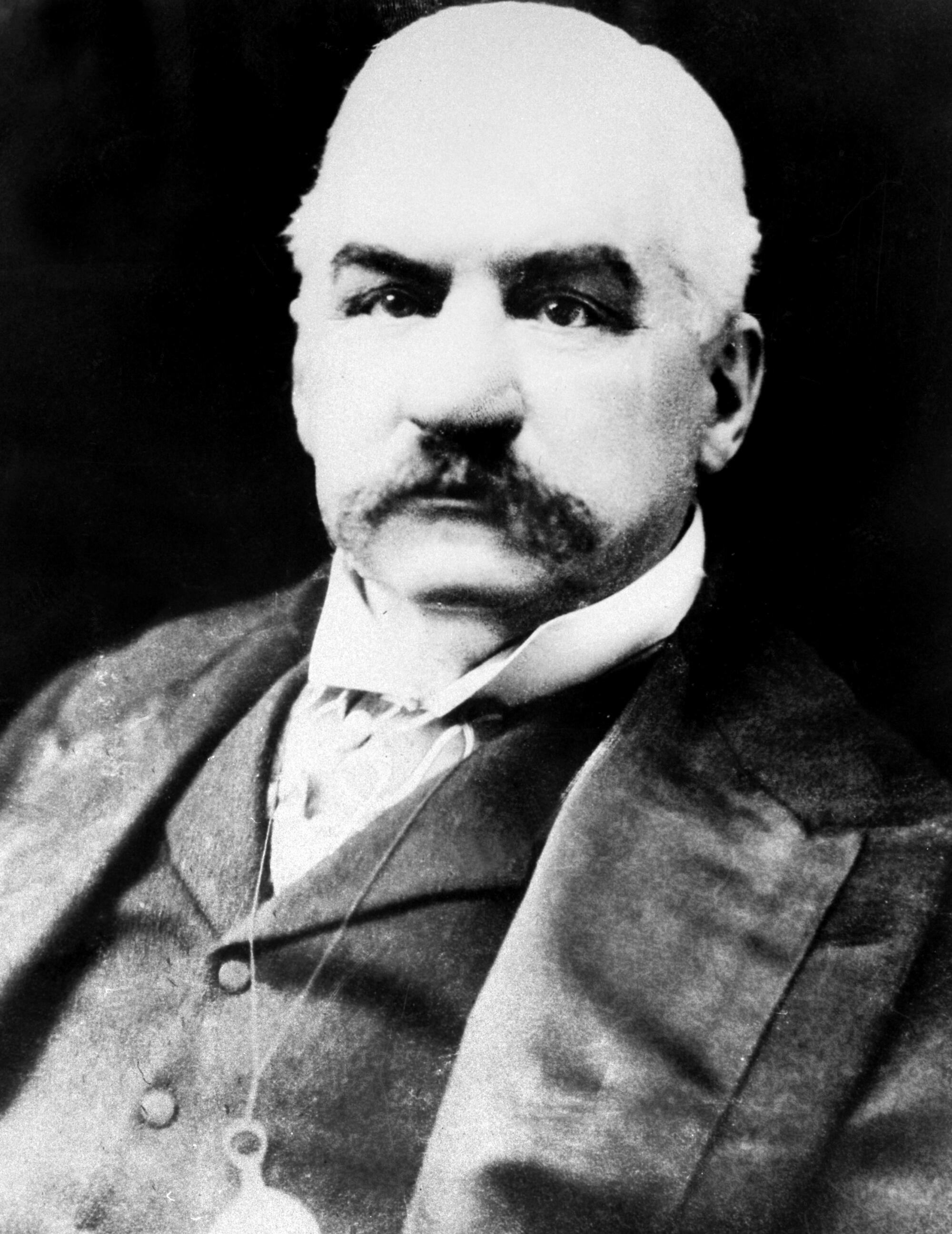

Impressive as its features were, the 1.75-pound watch may be just as notable for whom it was believed to be made: John Pierpont Morgan.

Around 1905, the Gilded Age tycoon commissioned the English firm J. Player & Son to create the timepiece, people familiar with the watch have asserted over the decades. It cost 1,000 pounds — or about $5,000 at the time — and took four years to make.

Just a few years after the watch’s completion, Morgan died in 1913 at the age of 75. The banking magnate’s death is said to have touched off a long, peripatetic journey for the timepiece, which eventually found its way into the hands of an enigmatic antiquities dealer in New York.

Then, in the mid-1970s, the pocket watch disappeared, spawning an enduring mystery. I set out to solve it in spring 2020.

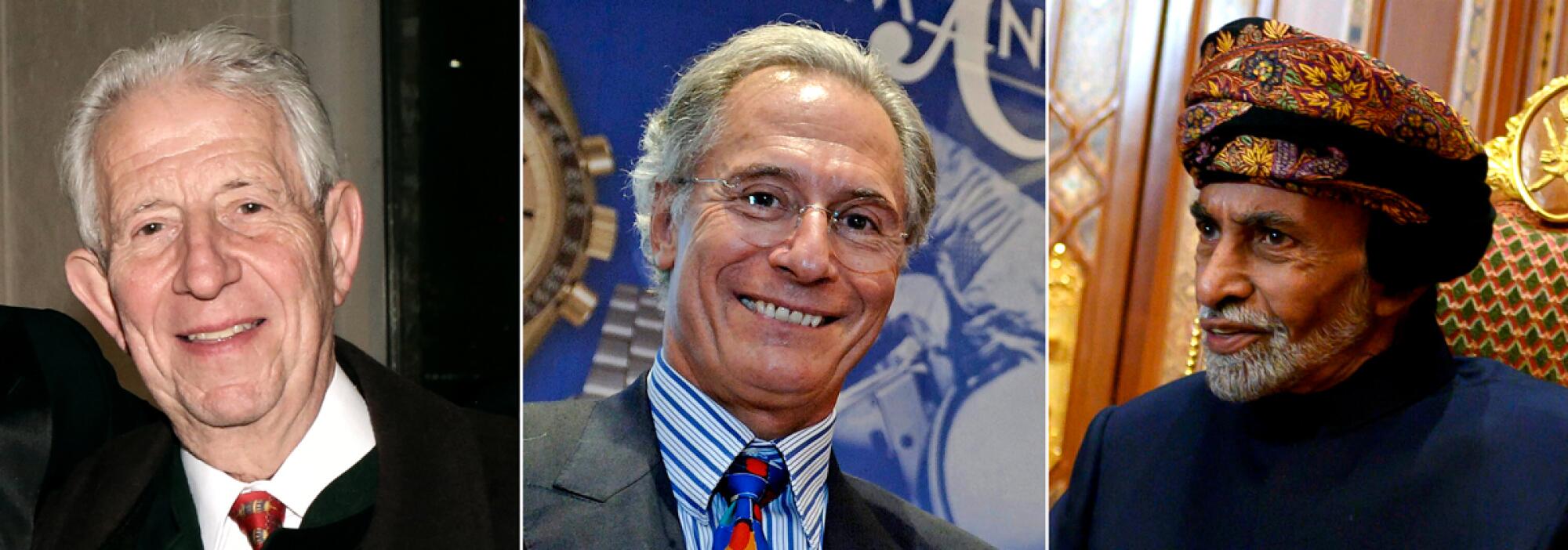

The effort plunged me into the baroque world of high-end antiquities, where a strange globe-spanning story entangled the estate of a La Jolla aviation mogul, an accountant from England, an Italian auctioneer, a watch-collecting Middle Eastern sultan and the archduke of Austria.

The J. Player watch is not the only important timepiece to vanish. The Omega Speedmaster that Buzz Aldrin wore on the moon is lost. So is a 19th century Breguet created for a Neapolitan queen that is thought to be the first wristwatch ever made. But the J. Player pocket watch, called a supercomplication because of its many features, stands out for its audacious intricacy.

Complex watchmaking — once the province of kings and queens — captivated early 20th century American industrialists, who were then emerging as the country’s version of royalty. They commissioned increasingly elaborate examples, and it became a competition of sorts. There was widely considered to be a winner: the Graves supercomplication. Made by Patek Philippe for banker Henry Graves Jr. in 1933, the pocket watch included 24 complications — industry jargon for functions — and was for decades touted as the most complex timepiece ever made. It sold at auction for $24 million in 2014, then a record.

The J. Player pocket watch can claim a record too: It is the most complicated timepiece ever made by a British watchmaker, experts said. And while it’s a safe bet that it would be worth millions, its value as a symbol of Great Britain’s watchmaking tradition transcends dollars and cents.

“The watch was, and remains, a hugely important part of our cultural heritage,” said watchmaker Robert Loomes, technical director of Loomes & Co. of Stamford, England.

I’ve been intrigued by horology — the study of the measurement of time — ever since I was a little kid with a replica Dick Tracy wristwatch (no, the two-way radio didn’t work). Back then it was a simple pleasure, but as I got older, my interest deepened. I became fascinated by the idea that something powered by gears, wheels, levers and springs could bring order to the ephemeral passage of time. And when I first strapped on my late grandfather’s gold watch, I felt the thrill of an heirloom that could bind generations.

So the mystery of the J. Player supercomplication resonated deeply, and finding it teetered toward an obsession.

But my search for the pocket watch didn’t pick up until I got a pivotal clue. It came from a descendant of Marie Antoinette’s mother.

My copy of Antiquarian Horology, purchased on EBay for $9, wore its five decades well. The September 1974 journal, dog-eared and smelling of pipe smoke and mothballs, included the first published reference to Morgan commissioning the timepiece. It also marked the last time its whereabouts were disclosed.

In a letter to the editor, New York antiquarian Jan Skala announced his ownership of the watch. Describing it, he invoked the mustachioed robber baron: “It was made in the first decade of this century for J.P. Morgan.”

Skala didn’t say how he acquired the watch, explaining only that it had “come into [his] possession.” He may have bought it from the late Benjamin Mellenhoff, a former head watchmaker at Tiffany & Co. who as of 1947 owned the timepiece, according to a contemporaneous magazine article.

Skala’s letter quoted extensively from a 1909 edition of the Horological Journal, which provided the first account of the watch in an essay by J. Player & Son. “It has been made expressly to the order of an American gentleman, who is an enthusiast in complicated horological productions, and what is perhaps rarer, has also the taste and appreciation for fine workmanship,” the Coventry, England-based company wrote, making no mention of Morgan.

Still, that description fits the financier. A major collector, Morgan hoarded art, coins, furniture and watches, amassing thousands of objects. His trove of timepieces numbered in the hundreds, with some dating as far back as the 16th century. They were listed in a 1912 volume that does not reference any J. Player timepiece, according to Sophie Harding of the Morgan Library & Museum in New York. But, she said, the catalog does not include watches from the 20th century. And Morgan had plenty.

The banker’s contemporary timepieces were fabricated in England “by the finest names of the day,” according to a 2019 article published by horology website SJX Watches that had sparked my interest in the J. Player watch. The story was unequivocal: The timepiece was commissioned by Morgan and had “arguably the greatest provenance of all super-pocket watches.”

But Skala was the only person with direct ties to the watch who claimed it had been made for Morgan — and he was a salesman by trade. There was, however, someone else who could vouch for the watch’s origins: a descendant of its maker.

Carl Player is the great-great grandson of J.W. Player, the son of the founder of J. Player & Son and the watchmaker who created the timepiece.

An accountant who lives in his family’s native Coventry, Carl Player, 27, said his grandfather John Player told him about the timepiece and its connection to Morgan several years before he died in 2019.

That aligns with the recollections of Loomes, chairman of the British Horological Institute. He said that John Player mentioned Morgan while visiting Loomes & Co.’s office nearly a decade ago, explaining with pride that “one of the most famous people in the world” had commissioned the watch. And that wasn’t the first Loomes had heard of it: BHI’s librarian told him about the banker’s ownership of the timepiece about 25 years ago, he said.

Although the pocket watch’s exact specifications are hard to discern, it included 18 complications by one expert’s count. “No other watch has combined such a variety of different mechanisms,” the company boasted in 1909, the year it was completed.

There was little time for J. Player & Son to revel in the triumph. The firm shuttered in 1910. It had been battered by competition from upstarts that were harnessing new technology to turn out less expensive watches, according to an obituary for J.W. Player published by the Horological Journal in 1956.

But family lore suggests that something closer to home played a darkly poetic role in the company’s downfall. Carl Player said that the business was devastated by “the amount of resources they spent” to create the special watch.

J. Player & Son was undone by its masterpiece.

I connected with Carl Player in April 2020, after coming across his posts on internet message boards devoted to horology. He’d been looking for the J. Player supercomplication for several years.

“I just think it’s a massive achievement for my family and England,” he said.

Player had traced the watch’s ownership history to Skala, but no further.

So I dug in. I thought that learning about Skala — and anyone else who possessed the watch — could help me track it down.

Skala cut a distinctive figure in a trade known for its share of eccentric personalities. A 1967 story in the New York Daily News said the Prague native trafficked in “gold timepieces shaped like orchestra instruments.” He was described as a “white-haired pixie” in a 1978 New York Woman article.

The antiques dealer operated a shop on 47th Street in Manhattan that offered collectibles including pocket watches, Faberge eggs and ornate cigarette cases. He was also known to acquire rarities on behalf of discerning clients. A 1978 New York Times story said that he won 17 lots — all gold and enameled boxes — at an auction of items from the estate of Henry Ford II. Skala, who used code names while bidding, said three were bought on behalf of European museums. Total price tag: $314,100.

Skala clearly ran in circles where the J. Player supercomplication would be of interest.

After hand-finishing the stainless-steel case of one of his timepieces in a whirring industrial polisher, watchmaker Cameron Weiss carefully submerged it in an ultrasonic cleaning tank.

Player wondered if Skala, who died in 1996, had bequeathed the watch to a relative, but no living kin could be located. Player also thought it could have been stolen from Skala, explaining that he’d read accounts of the antiquarian “being conned out of items.” Indeed, jewelry dealer Louis Heimann was convicted of fraud for orchestrating a scheme that involved swindling Skala and another merchant out of precious objects worth millions of dollars.

None of the digital records related to the case mentioned the specific items that Heimann took from Skala — but one filing offered a possible path forward. It noted that Géza von Habsburg was chairman of Christie’s in Switzerland when the company auctioned collectibles consigned by Heimann that came from Skala’s shop.

Von Habsburg, 81, is the archduke of Austria — he’s a descendant of Marie Antoinette’s mother — and an authority on Faberge eggs. When I reached out to him, Von Habsburg wrote that he recalled Skala as a buyer at auctions, but knew little else.

Von Habsburg said that he’d messaged a friend, Antiquorum auction house founder Osvaldo Patrizzi, about the timepiece. He explained that Patrizzi remembered Skala owning the watch — and that Skala had parted with it.

“He sold it to a collector in San Diego,” wrote Von Habsburg. “I can say no more.”

Before long, I was corresponding with Patrizzi. Eventually, he shared the name of the buyer: Sam Bloomfield.

Sam Bloomfield was a La Jolla-based millionaire who had made his fortune in aviation.

As president and chief engineer of Wichita, Kan.-based Swallow Airplane Co., Bloomfield co-designed the Swallow Model C in 1936, and accumulated 23 U.S. patents, according to his biography on the website of Wichita State University, where he and his wife, Rie, were benefactors.

In 1956, Swallow shut down and the Bloomfields left for California, settling in La Jolla.

Bloomfield’s appetite for collecting went into overdrive. He acquired Ferraris, Stradivarius and Guadagnini violins, and, of course, pocket watches. He had a taste for English timepieces, amassing several rare examples. To Bloomfield, the J. Player watch must have been something of a Holy Grail.

It’s a tale of dedication, perseverance and obsession: one man’s effort to write the definitive history of the Illinois Watch Co.

When Patrizzi met Skala in 1975, the antiquarian told him about Bloomfield.

The collector had recently visited Skala’s shop without advance notice, Skala told Patrizzi. “It was by chance that the watch was in the store and not in the bank where he normally kept the most valuable items,” Patrizzi said. “When Skala showed him the watch, [Bloomfield] wanted it at all costs.”

Skala’s asking price: $250,000 (about $1.3 million today). It was, said Patrizzi, an exorbitant sum. But, according to Skala, Bloomfield bought it “without hesitation.” Skala said that he was pleased with the sale, but sad too, because he knew he’d never again possess such a complex watch, Patrizzi recalled.

But, as with J.P. Morgan, Bloomfield’s time with the watch was brief. He died in 1979.

The Bloomfields did not have children, and after Rie’s death in 1996, the couple’s foundation began disbursing its assets. It sold two timepieces over the years, but has no record of a sale of the J. Player pocket watch, according to Cheryl Moffatt, a director at financial services firm CBIZ & Mayer Hoffman McCann, who handles the foundation’s accounting. She believes “the watch was no longer in the possession of the Bloomfield Foundation or estate” by the time she and her colleagues got involved in the 1990s.

I shared this information with Patrizzi, who wondered whether the watch had been acquired by the Sultan of Oman Qaboos bin Said, a prolific collector. But the sultan died in 2020.

Improbably, though, he would bring this story to a close — and not in the way you might expect.

The late sultan and J.P. Morgan had at least one thing in common: Both were customers of luxury goods emporium Asprey of London.

The Omani ruler worked directly with John Asprey, who had led the family business. Hoping to speak with him, I reached one of Asprey’s sons, who instead suggested a conversation with Andrew Crisford, an antiquarian horologist and founder of rare timepieces dealer Bobinet.

I wrote to London-based Crisford, who replied to say that he knew of the J. Player pocket watch. Crisford said he first saw it in the mid-1970s, when he was visiting a New York watchmaker who had just overhauled the timepiece. When he inquired about buying it, the man explained that it belonged to Skala but was being sold to Bloomfield.

Crisford got to know Bloomfield in the late 1970s, visiting him in La Jolla. Despite the collector’s wealth, there was a casual warmth to the get-togethers, Crisford explained on a telephone call. “He would serve you coffee, but it was always with a cake that Mrs. Bloomfield had made,” he said.

The two horologists bonded over their shared interest in timepieces made by Breguet, of which Bloomfield owned many important examples, Crisford said, including a pocket watch that housed the world’s first tourbillon — a mechanism that improves timekeeping by suspending componentry in a rotating cage. (The J. Player supercomplication had a tourbillon, too.)

Over the course of several years — beginning before Bloomfield’s death and concluding in the years after it — Bobinet acquired his entire collection of timepieces. The J. Player watch was purchased in 1983 for an undisclosed sum and sold the same year by Bobinet to one of its clients, Crisford explained.

The pocket watch, he said, is “still with the person that we sold it to.”

My heartbeat thrummed in my ears as static danced in the background of the transatlantic call. The J. Player supercomplication wasn’t lost. But Crisford wouldn’t name the owner.

“If you ... had a collection of such watches, you really would not want your name in the Los Angeles Times,” he said.

Still, Crisford — who shared contemporary photographs of the J. Player — made it clear that the pocket watch is cherished. “The owner fully understands what it is,” he said. “And considers himself very privileged to own it.”

I explained that Carl Player worried that the watch had been lost, but Crisford had a message for the descendant of the Coventry watchmakers: “I saw it recently. It is perfectly safe.”

The J. Player & Son supercomplication made sense of the universe. It decoded the mysteries of the sun, moon and stars. It charted the advance of existence. But it did something else — a feat that its creator probably never could have imagined. The pocket watch had, over the course of more than 100 years, bound an unlikely group of people.

John Pierpont Morgan. Jan Skala. Sam Bloomfield.

And Carl Player.

There was one last thing to do — tell him what I’d discovered.

“Wow. I didn’t think we’d get that far,” Player said. “I’m just shocked, but I’m really happy it’s still around.”

Player said he could live without knowing who owns the pocket watch, secure in the knowledge that his family’s masterpiece is treasured.

That was enough.

Times staff members Scott Wilson and Nani Sahra Walker contributed research to this report.

A gold watch said to have been made for J.P. Morgan disappeared, prompting a hunt that plunged into the baroque world of high-end antiquities.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.