Honduras at crossroads in election to end corrupt rule of Juan Orlando Hernandez

SAN PEDRO SULA, Honduras — Three years before he was elected Honduras’ president in 2013, Juan Orlando Hernandez impressed U.S. State Department insiders as a charming, relatively young, law-and-order candidate capable of stabilizing one of the world’s most violent countries.

But Hernandez has left the nation in ruins as tens of thousands of Hondurans flee for better lives in the U.S. and elsewhere. The president’s years in power have been marked by human rights violations, extrajudicial killings, stolen public money, poverty and complicity in drug trafficking at the highest levels of government. Sunday’s elections are arguably the most consequential in decades to restoring order in this troubled Central American country.

“Juan Orlando is leaving us with a broken country,” said Lenín Laínez, a congressman for the opposition Libre party. “A country in debt, with serious narco-corruption, with high levels of criminality and one of the most unequal populations in Latin America.”

The ruling National Party’s dependence on drug money and elite military units has led Hondurans to call their land a “narco-dictatorship.” This atmosphere is part of a wider trend of backsliding in democracy across the region, from Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua to Nayib Bukele in El Salvador and Alejandro Giammattei in Guatemala. It has spurred mass emigration in recent years.

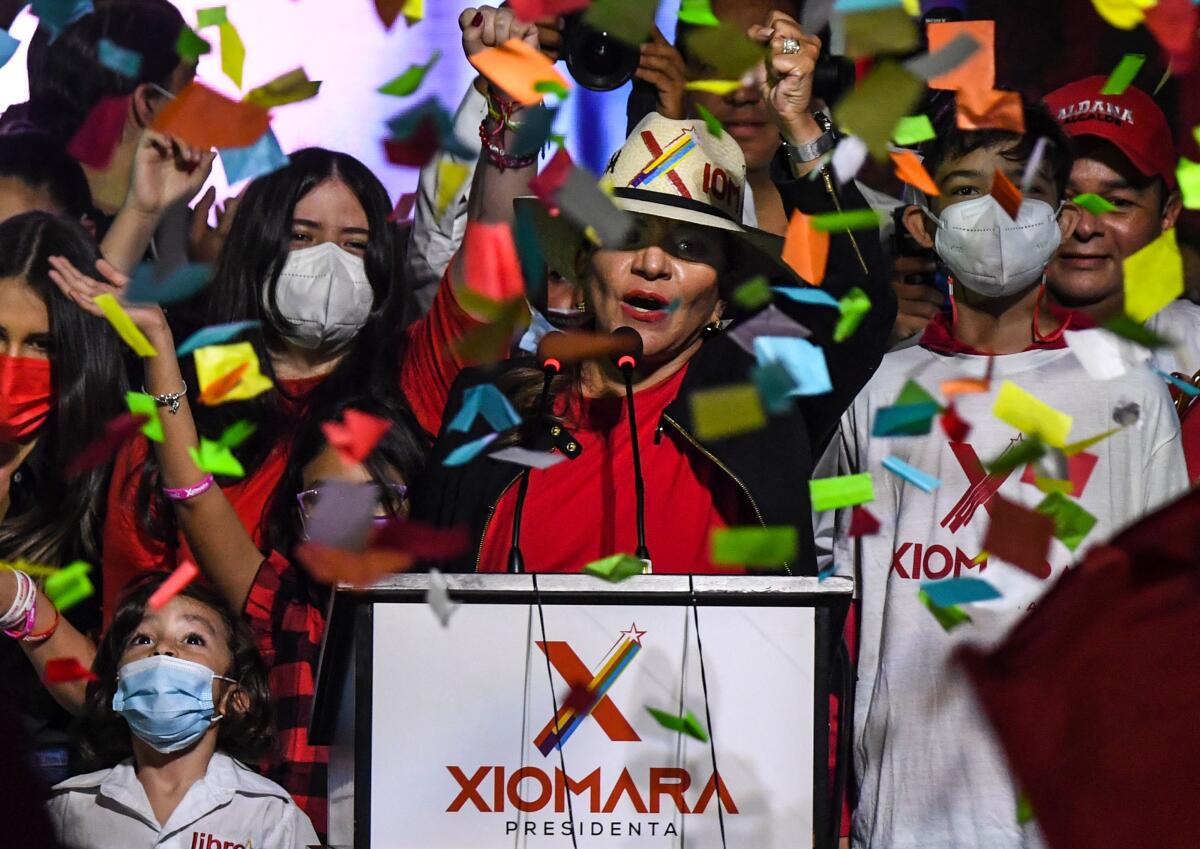

Honduras has been in crisis since a 2009 military coup that Washington did not move to stop. That led to the eventual rise of Hernandez, whom U.S. prosecutors accuse of consolidating his power with cartel money. The two leading presidential candidates on the ballot embody the contradictions of the violent post-coup era: Nasry Asfura, the ruling right-wing National Party candidate, is backed by Hernandez. Xiomara Castro, the wife of Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, who was ousted in the coup, is a popular progressive candidate.

“Twelve years of illegal government hasn’t done anything for Hondurans,” Castro said in a Nov. 20 speech. “They’ve only dedicated themselves to their own businesses and swindling off state money ... while the people live as victims of misery and insecurity.”

The National Party “has left us with a Honduras where it’s impossible to access quality, free healthcare or education,” said Anabel Melgar, a member of the National Front for Youth in Resistance. “They embezzled the health fund, and thousands of people have died because, with the money from the fund stolen, they handed out [poor-quality] pills.”

One of the trademarks of Hernandez’s time in office — aside from doling out benefits and keeping the allegiance of government workers — has been the expansion of the army into the public space and creation of paramilitary and elite units implicated in human rights violations.

Land rights activist Yoni Rivas comes from the Aguán Valley, where hundreds have been killed in battles between peasants and palm oil corporations, and where paramilitary groups connected to the Honduran army are driving migration out of the country. If Asfura wins, Rivas said, it will be “more corruption, more criminality, more persecution and more of the same.”

On the country’s north coast, the Afro-Indigenous Garifuna population has been engaged in years-long battles with tourism and palm oil companies — long favored by the National Party over Indigenous citizens — which have sought to take over their coveted beachfront land.

Darwin Centeno, a Garifuna fisherman from Triunfo de la Cruz whose cousin Sneider Centeno was a prominent Garifuna activist abducted by a police-linked death squad in July 2020, said the National Party’s legacy is one of “committing damage against our community, disrespecting our ethnic rights.”

But the National Party is skilled at mobilizing voters, which could stop the progressive Castro from becoming the country’s first woman president with her promises to wipe away the old ways of power. Her husband had been accused of taking bribes while he was president — a charge he denied.

Castro proposes loosening Honduras’ notoriously strict abortion laws and has suggested convening a National Assembly to rewrite the constitution to be more inclusive. She is frequently portrayed in commercials — as well as on ominous red billboards throughout the country — as a Trojan horse for communism, much like her husband was depicted by opponents in the late 2000s.

Despite the campaign against her, Castro, a candidate for the center-left Libre party, holds a narrow lead over Asfura in opinion polls.

The closeness of the race has heightened fears of postelection violence. It wouldn’t be the first time. In 2017, the popular opposition candidate Salvador Nasralla appeared on track to victory, but irregularities in the voting system indicated potential fraud, sparking months of protest and deadly state repression. Hernandez was eventually declared the winner.

“There’s an enormous possibility of fraud,” said Jessenia Molina, a journalist and human rights defender from the town of Tocoa. “I don’t doubt it one bit.”

“You have to be ready for that possibility,” said Tania Iden, a Garifuna woman.

Asfura, known to supporters as Papi a la orden (Daddy at your service), has focused on job creation and continuing Hernandez’s security policies. But Asfura is tainted by his years in the National Party: He faced an investigation over the embezzlement of $1 million of public funds. Critics fear, however, that the National Party’s suspect campaign tactics may tip the election in an impoverished nation battered by natural disasters.

Many have accused the National Party of attempting to buy preelection loyalty: “They’ve turned schools into delivery centers for gifts [stoves, beds, bikes, fridges, money] through National Party activists called Guias de Familia,” said Melgar of her home department, Intibucá. “They tell those people to vote for the National Party in exchange for those gifts.”

A central question hanging over the elections is whether Hernandez, who will leave office in January, will join the list of Honduran politicians extradited to the U.S. on drug trafficking charges. During the trial of his brother, Tony Hernandez, who was sentenced to life in prison this year on weapons and drug trafficking charges, U.S. prosecutors alleged the president offered to dispatch troops to defend a trafficker’s cocaine lab. The president, witnesses alleged, said he would “shove coke up the noses of the gringos.”

A White House aide recently told the New Yorker that, upon being briefed on President Hernandez’s record, Vice President Kamala Harris sought to “go get him now,” but was cautioned by advisors about targeting a head of state. It’s unclear if that hesitancy will change after the election, though some efforts have been made by the Biden administration to expose corruption: This summer, the U.S. released a list that named 55 alleged corrupt officials throughout the region, including former President Porfirio Lobo and his wife. Many Hondurans noted that Hernandez was not on the list.

Honduras has been a close U.S. ally for decades. But over the last year, as rumors of potential extradition by the Drug Enforcement Administration have grown, Hernandez sought to cultivate alternative alliances. In April he gave a speech in which he suggested strengthening relations with China, and in late October he held an unexpected meeting with the autocrat Ortega in neighboring Nicaragua. Some Hondurans believe the president will seek refuge in an employment and economic development zone, known by the acronym ZEDE, a controversial project for autonomous corporate enclaves in Honduras where an opaque new legal system could make him immune from extradition.

Many here fear entrenched networks of corrupt actors, including those supporting Asfura, will make it almost impossible for change: “If Xiomara wins, it’s going to be extremely complicated for her. The corrupt power structures in this country won’t let her take away their benefits,” said Molina. “There’s a whole group that will wage war against her.”

Olson is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.