U.S. publishes list of Central American officials suspected of corruption

GUATEMALA CITY — The U.S. State Department has named more than 50 current and former officials, including former presidents and active lawmakers, suspected of being corrupt or undermining democracy in three Central American countries.

Many of the cases were known in Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, but the inclusion of names on the U.S. list buoyed the hopes of anti-corruption crusaders. The list was provided to the U.S. Congress in compliance with the “U.S.-Northern Triangle Enhanced Engagement Act.”

Its release comes at a time when the Biden administration has given new attention to corruption in the region as one of the factors driving Central Americans to migrate to the United States.

Congress’ call for the report reflects growing concern “about the level of systemic corruption in the countries of the Northern Triangle, the significant backsliding that we’ve seen across the region in the last several years,” and the need to “ensure that our assistance is not ending up in the pockets of corrupt officials or their allies,” said Adriana Beltran, director of citizen security at the Washington Office on Latin America, a nongovernmental organization focused on human rights issues. The report is known as “the Engel list,” after then-Rep. Eliot L. Engel (D-N.Y.), who pushed for it last year.

Among the most prominent figures on the list are former Honduran President Porfirio Lobo and former First Lady Rosa Elena Bonilla de Lobo. The State Department report says Lobo took bribes from a drug cartel and his wife was involved in fraud and misappropriation of funds. Both deny the allegations. Bonilla’s conviction on related charges was invalidated by the Supreme Court last year and she is awaiting a new trial.

Perhaps as significant as Lobo’s inclusion or that of more than a dozen current lawmakers, was the omission of current Honduras President Juan Orlando Hernández. U.S. prosecutors in New York have signaled suspicion that Hernández funded his political ascent with bribes from drug traffickers, but he has not been formally charged.

He has denied any wrongdoing. His brother, former federal lawmaker Juan Antonio “Tony” Hernández, was sentenced in New York in March to life in prison.

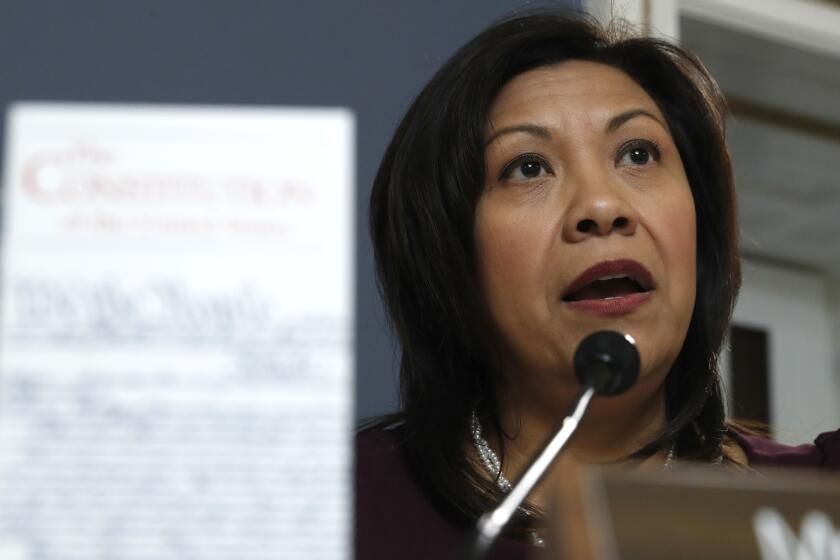

California’s Norma Torres fled Guatemala at 5. Now the only Congress member from Central America says the immigration debate is ‘very, very personal.’

Honduran analyst and former lawmaker Raúl Pineda Alvarado said that there had been high expectations for the list, but that it did not include the top perpetrators, leaving him underwhelmed: “If this is the way the United States Congress wants to battle corruption in Honduras, it’s like wanting to cure cancer with aspirin.”

Instead of naming those who call the shots and control resources, most of the names were “secondary perpetrators,” he said.

“This Engel list, in a way, was very inspiring; you thought it would be a devastating blow to the real corruption heavyweights,” Pineda said. “But unfortunately those hopes have been frustrated.”

Former Cabinet officials in El Salvador, along with a judge and the Cabinet chief for President Nayib Bukele, were placed on the list. Chief of Staff Carolina Recinos has kept a low profile since her name appeared on a shorter State Department list in May, but administration officials say she has maintained her presence in the presidential offices.

With his carefully crafted social media presence and populist politics, Nayib Bukele has become one of the most popular politicians on Earth. Now just one question remains: What does he want?

Thursday’s list said she “engaged in significant corruption by misusing public funds for personal benefit” and participated in a money laundering scheme.

The list also included two former presidents of the Legislative Assembly, including Walter Araujo, who left the conservative Arena party to become a high-profile leader of Bukele’s New Ideas party.

The list said Araujo was included for “calling for insurrection against the Legislative Assembly and repeatedly threatening political candidates.” Araujo reacted on Twitter, saying that “gringos” and unscrupulous journalists wouldn’t silence him.

“If for defending my nation and my people they put me on the Engel list ... they can put me there 100 times more,” he wrote.

Jean Manes, a former U.S. ambassador to El Salvador, who recently returned temporarily as the charges d’ affaires, said in a video statement that U.S. strategy in the region centers on battling corruption because it is the greatest impediment to development.

The Biden administration aims to reduce immigration from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, the so-called Northern Triangle. Why target those nations?

She noted that people included on the list “immediately lose their visa to enter the United States.”

Eduardo Escobar, head of the public accountability organization Citizen Action in El Salvador, said he had met Wednesday with Victoria Nuland, the U.S. undersecretary of State for political affairs, on her visit to the country.

Escobar said that in some cases, the list lent credence to allegations that members of Bukele’s government were involved in corruption, as well as members of other political parties. He said now they would have to see if the Salvadoran Attorney General’s Office takes any action to pursue people on the list.

Bukele’s administration did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

In Guatemala, former President Alvaro Colom was accused of involvement in fraud and embezzlement in the case of a new bus system in Guatemala City. Current Supreme Court Justice Manuel Duarte Barrera allegedly “abused his authority to inappropriately influence and manipulate the appointment of judges to high court positions.” Another high court justice, Nester Vásquez, also meddled in the selection of judges, the report alleged.

Guatemala’s chief anti-impunity prosecutor, Juan Francisco Sandoval, indicated Guatemala’s corruption extended far beyond those named on the list.

“I think they are missing a number who have been charged with corruption,” Sandoval said. “In the prosecutor’s office, we investigate hundreds of people and hundreds more have been convicted. I think they need to touch the high positions in the corrupt structures, especially those who finance it.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.