Can Biden find the right balance on immigration?

WASHINGTON — Democrats wielded demands to fix the nation’s broken immigration system as a cudgel against Republicans in the 2020 campaign. Elect us, went the argument, and we’ll stop the cruel treatment of migrants at the border and put in place lasting and humane policies that work.

A year into the Biden presidency, though, action on the issue has been hard to find and there is growing consternation privately among some in the party that the Biden administration can’t find the right balance on immigration.

Publicly, it’s another story. Most Washington lawmakers are largely holding their tongues, unwilling to criticize their leader on a polarizing topic that has created divisions within the party — especially as concerns mount over whether Democrats can hold on to power come next year.

It’s a hard balancing act to pull off, said Douglas Rivlin, spokesman for America’s Voice, an immigration reform group. And, especially when Republicans are unrelenting in their negativity toward the president, even a little friendly fire can be a challenge.

“It’s hard, but they’ve got to do it,” he said. “They’re going to face voters next year, all the people on [Capitol] Hill. Biden isn’t, they are. And they have to be clear they’re pushing Biden to be the Democratic president we elected, rather than being scared of the issues because the politics are difficult.”

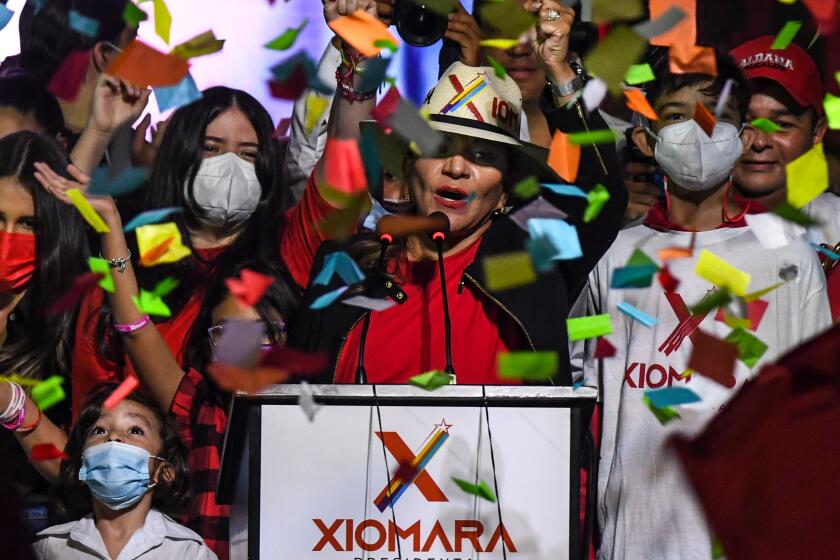

Hondurans will vote Sunday to replace corrupt President Juan Orlando Hernandez in what is arguably the country’s most important election in decades.

Democrats have pointed to the recent House approval of a huge spending bill backed by the White House that would allow for expanded work permits and some other, less ambitious immigration provisions. When Biden took office, he promised a pathway to U.S. citizenship for millions of people in the country illegally. Democrats say the measures in the spending bill are enough to show the party won’t shy away from the immigration issue during next year’s midterms.

“I don’t see it as as the fault of the president per se or ... these challenges that we’re facing today, solely falling on the shoulders of the president,” said Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), whose El Paso district lies across the border from Juarez, Mexico. “It is a collective obligation that we have and and I think Democrats have solutions and we need to lean in on them.”

Her fellow Texas Democrat, Rep. Joaquin Castro of San Antonio, ducked when asked if House members in swing districts will be forced to run away from Biden in 2022, saying “I’m going to wait on political discussions.”

But Castro added that the party had done as much as it could on immigration this session, given Senate rules that have prevented more consequential legislation on the issue from advancing with the required minimum of 60 votes in that chamber.

“Right now, Democrats have control of the White House, the Senate and the House and we have pushed as hard as we can with the number that we have in the chambers to get protections from deportation, workplace permits, driver’s licenses, travel abilities,” Castro said.

Former Democratic Rep. Beto O’Rourke, who recently announced he’d run for Texas governor, has been one of a few Democrats to put immigration front and center, heading almost immediately to the U.S.-Mexico border after he announced he was running, where he suggested the White House is doing its party no favors.

“It’s clear that Biden could be doing a better job at the border,” O’Rourke said during an interview with KTVT TV in Dallas-Fort Worth. “It is not enough of a priority.”

Like most top Democrats, O’Rourke will have to counter the narrative pushed by Republicans that an increase in the number of people crossing the border illegally this year has reached “crisis” levels. Incumbent Texas Republican Gov. Greg Abbott’s campaign accused O’Rourke of supporting Biden’s “open borders” policies and financed billboards along the border featuring O’Rourke’s face morphing into that of the president.

Nick Rathod, O’Rourke’s campaign manager, sees “neglect, I think by Democrats across the board, not just the Biden administration, in engaging in an authentic manner in those communities” along the border.

“It’s sort of created a vacuum. What we want to do is fill that space.”

But immigration is a complex issue, and no administration has been able to fix it. And Biden is trapped between the conflicting interests of showing compassion while dealing with migrants who come to the country seeking a better life, but illegally.

The administration has said it is focusing on root causes of immigration and working to broker long-term solutions that would make migrants want to stay in their homelands. They’ve pushed through regulations that aim to adjudicate asylum cases faster so migrants don’t wait in limbo, and they’ve worked to diminish the massive backlog of cases.

But mostly, Biden has spent much of the past year undoing Trump-era rules widely viewed as cruel that clamped down on asylum seekers, gutted the number of refugees allowed to the U.S. and then shuttered the border entirely in the name of COVID-19.

Despite that effort, Biden has faced a heap of criticism from progressives and immigrant advocates who say he is still making too much use of inhumane Trump-era policies.

One of the most criticized is the “Remain in Mexico” program, which requires migrants to wait for resolution of their immigration claims across the border in Mexico, often in fetid, makeshift refugee camps. It was put on hold after a judge ruled it was improper, but according to court papers, the Biden administration is waiting on final agreements with Mexico to start doing it again.

“We reject a system where people facing life-and-death consequences are forced to navigate a complex legal system — in a language they may not speak and in a culture which they may not be accustomed to — alone,” the Catholic Legal Immigration Network said in a statement.

Another is a provision, known as Title 42, that gives federal health officials powers during a pandemic to take extraordinary measures to limit transmission of an infectious disease and which has been used to keep asylum seekers out. The White House has appealed a judge’s ruling that ended the regulation.

The administration has used the provision to justify the deportation of Haitian migrants who entered Texas. After viral images surfaced of U.S. Border Patrol agents on horseback using aggressive tactics, Biden’s team took heat from even the staunchest of allies.

Republicans, meanwhile, are hammering on the issue of border security, intent on keeping it in the headlines. The issue remains a high priority to some voters. A CNN poll this month showed 14% of Americans identified immigration as the top issue facing the country, behind the economy and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The U.S. Border Patrol reported more than 1.6 million encounters with migrants along the U.S.-Mexico border from September 2020 to September 2021, more than quadruple the number in the prior fiscal year and the highest annual total on record.

The number of encounters had dropped over the previous 12 months to around 400,000 as the pandemic slowed global migration. But the rebound is now higher than the previous record set in 2000, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection data. The tally includes both expulsions when migrants are turned away immediately and apprehensions when they’re detained by U.S. authorities, at least temporarily.

Though career immigration officials warned of a coming surge, the U.S. system is still ill-equipped to manage such a crush. Border stations are temporary holding places not meant for long-term care. It’s a massive logistical challenge, especially when dealing with children who cross alone and require higher standards of care and coordination across agencies.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.