In a first for Latin America, International Criminal Court to investigate abuses in Venezuela

CARACAS, Venezuela — The International Criminal Court is opening a formal investigation into allegations of torture and extrajudicial killings committed by Venezuelan security forces under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule, the first time a country in Latin America is facing scrutiny by the court for possible crimes against humanity.

The opening of the probe was announced Wednesday by ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan at the end of a three-day trip to Caracas, the Venezuelan capital.

Standing alongside Maduro, Khan said he was aware of the political “fault lines” and “geopolitical divisions” that exist in Venezuela. But he said his job was to uphold the principles of legality and the rule of law, not settle scores.

“I ask everybody now, as we move forward to this new stage, to give my office the space to do its work,” he said. “I will take a dim view of any efforts to politicize the independent work of my office.”

While Khan didn’t outline the scope of the ICC’s investigation, it follows a lengthy preliminary probe started in February 2018 — later backed by Canada and five Latin American governments opposed to Maduro — that focused on allegations of excessive force, arbitrary detention and torture by security forces during a crackdown on anti-government protests in 2017.

Human rights groups and the U.S.-backed opposition immediately celebrated the decision. Since its creation two decades ago, the ICC has focused mostly on atrocities committed in Africa.

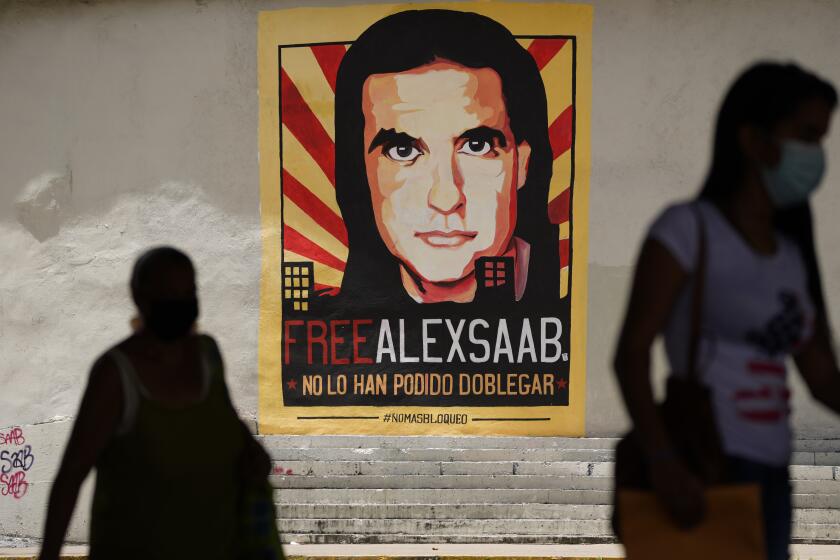

A senior U.S. official says that a top fugitive close to Venezuela’s socialist government has been put on a plane to the U.S. to face money-laundering charges

“This is a turning point,” said Jose Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director for Human Rights Watch. “Not only does it provide hope to the many victims of Maduro’s government, but it also is a reality check that Maduro himself could be held accountable for crimes committed by his security forces and others with total impunity in the name of the Bolivarian revolution” started by former President Hugo Chavez.

It could be years before any criminal charges are presented as part of the ICC’s investigation.

Maduro said he disagreed with Khan’s criteria in choosing to open the probe. But he expressed optimism over a three-page “letter of understanding” he signed with the prosecutor that would allow Venezuelan authorities to carry out their own proceedings in search of justice, something allowed under the statute that created the ICC.

“I guarantee that in this new phase we will leave the noise to the side and get down to work so that, together, the truth can be found,” said Maduro.

British judge refuses to give Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro control of gold in Bank of England vault.

Maduro’s government last year also asked the ICC to investigate the U.S. — which is not among the ICC’s 123 member states — for its policy of economic sanctions focused on removing Maduro. Venezuela considers the U.S. sanctions tantamount to “unlawful coercive measures” that have spelled poverty for millions of Venezuelans.

Khan’s predecessor, Fatou Bensouda, had indicated there was a reasonable basis to conclude that crimes against humanity had been committed in Venezuela, echoing the findings of the United Nations’ own human rights council last year. But she left the decision to open any probe to her successor, Khan, a British lawyer who took the reins of the ICC earlier this year.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.