Rich countries are hoarding COVID-19 vaccines. Elsewhere, the pandemic may keep killing for years

MEXICO CITY — The race to vaccinate the world against a once-in-a-century pandemic has begun in an all-too-familiar way: Every country for itself.

Rich nations have gobbled up nearly all the global supply of the two leading COVID-19 vaccines through the end of 2021, leaving many middle-income countries to turn to unproven drugs developed by China and Russia while poorer states face long waits for their first doses.

“Richer countries will be able to vaccinate ... their whole populations before vulnerable groups in many developing countries get covered,” said Suerie Moon, co-director of the Global Health Center at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.

As a result, the pandemic may continue to kill people across much of the world for years, delay a global economic recovery and eventually resurge even in nations that manage to control it in coming months through vaccination.

Experts say the inequities are the predictable result of a global health system in which money often counts more than the public good — and where vaccines are costly commercial products developed and patented by a handful of huge drug companies.

The gap in access has sparked calls for emergency measures that would allow poorer countries to manufacture and import generic versions of COVID-19 vaccines.

In October, India and South Africa asked the World Trade Organization to waive intellectual property protections for those drugs, just as it did for some medications used to treat HIV — a move credited with saving millions of lives in Africa.

Humanitarian groups that support the plan — which they have dubbed “the people’s vaccine” — warn that without it, 9 out of 10 people in dozens of poor countries will miss out on COVID-19 vaccinations next year.

“If we do nothing it’s going to be well into late 2022 or early 2023 before even half of the low-income countries are vaccinated,” said Niko Lusiani, a senior advisor with Oxfam America, the global health charity.

The proposal is opposed by the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom — wealthy WTO members that helped finance vaccine development and argue that such innovation would be impossible without patent protection.

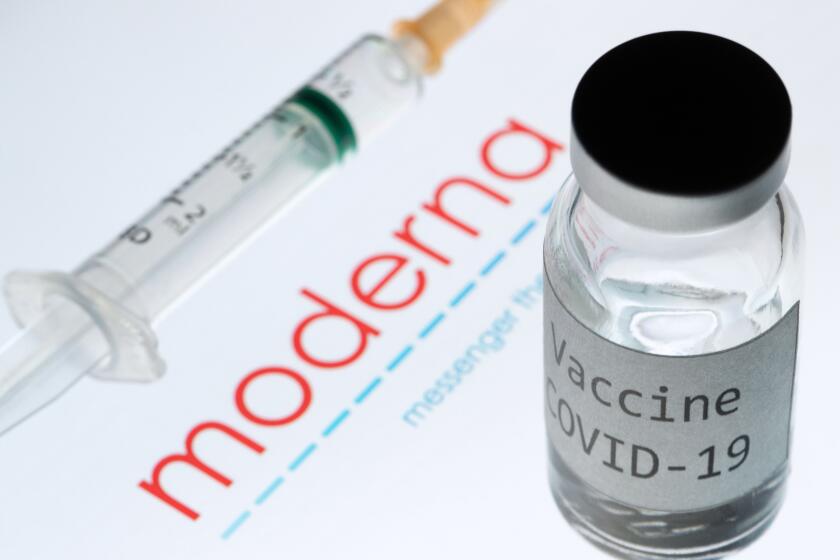

The U.S. government provided the vast majority of funding for development of the vaccine made by Moderna and the National Institutes of Health. It also struck purchase agreements — known as advance market commitments — with the drugmaker and with Pfizer and BioNTech while their vaccine was still being tested. Those deals reduced risk for the companies and allowed the U.S. to secure 300 million shots.

As the only vaccines currently authorized by the Food and Drug Administration, they are now being given to front-line health workers across the country.

The Food and Drug Administration grants emergency-use authorization to the COVID-19 vaccine from Moderna and the National Institutes of Health.

In all, the U.S. government has confirmed deals to buy 1.1 billion doses of a half-dozen vaccines in various stages of development, according to the Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University. The United States is expected to end up with far more doses than what is needed to vaccinate every American.

Other wealthy countries have bought an additional 2.9 billion doses in bilateral deals with drugmakers.

Although there has never been such global demand for the same few drugs at the same time, pandemic nationalism is an old phenomenon.

A decade ago, during the swine flu outbreak that killed more than a quarter of a million people worldwide, the United States and other wealthy countries snatched up nearly all the available vaccine. They agreed to share a limited amount with poorer countries only after ensuring they had enough to meet their own needs.

For the poorest nations, the best chance to obtain significant quantities of vaccine in 2021 rests with an initiative called Covax.

Launched by the World Health Organization and several nonprofits, it aims to promote equitable distribution of vaccines by negotiating favorable pricing with drug companies and giving all countries — rich or poor — equal access.

Nearly every country in the world — with the notable exception of the United States — signed on, in many cases simply as an insurance policy in case bilateral deals with drugmakers fall short.

The poorest nations, though, are depending on aid from wealthier members, which have so far contributed $2.4 billion to the cause. Covax officials say they need to raise an additional $4.6 billion.

“While it is great that Covax may be able to access these vaccine doses, it will depend on whether the corporations agree to the right price and donors give them enough money to pay for it,” Lusiani said.

Many countries saw the coronavirus as a ‘rich man’s disease’ imported by overseas travelers. It has since hit marginalized groups the hardest.

As of last week, according to the Duke Global Health Innovation Center, no country in sub-Saharan Africa had reached a deal to purchase vaccines on its own.

Even if it is fully funded, Covax aims to inoculate only up to 20% of people in each country by the end of 2021. In some countries with severe outbreaks, that could prove woefully inadequate.

Making matters worse, some rich participants have undermined the initiative by cutting additional side deals with drug companies, reducing the amount of vaccine available for Covax, the center found.

Last week officials from France and Canada — which has secured enough vaccine to inoculate each citizen five times — said they were developing a mechanism to allow nations to share surplus vaccine with other countries, but gave no time frame for when that could begin.

“We would absolutely be donating any excess capacity, but we will be taking it one day at a time,” said Karina Gould, Canada’s minister of international development.

Experts say that hoarding vaccines could ultimately harm rich countries.

A Rand Corp. study found that if only wealthy and vaccine-producing nations had access to the injections, the world economy would lose $292 billion in value compared with a scenario in which all countries had access.

“Even if Americans are immune to the virus, they will not be immune to economic losses of other economies being unable to get started again,” Moon said. “We’ve seen the limits to appealing to ethics and solidarity in this moment. We have to frame this not as development aid — this is an investment in getting the global economy moving again.”

There is another danger in not wiping out the virus worldwide as quickly as possible. It is unclear how long the vaccines offer protection from COVID-19, so even countries that achieve herd immunity next year — by inoculating at least 70% of their populations — eventually could be vulnerable to outbreaks again if the virus is allowed to simmer in poor countries.

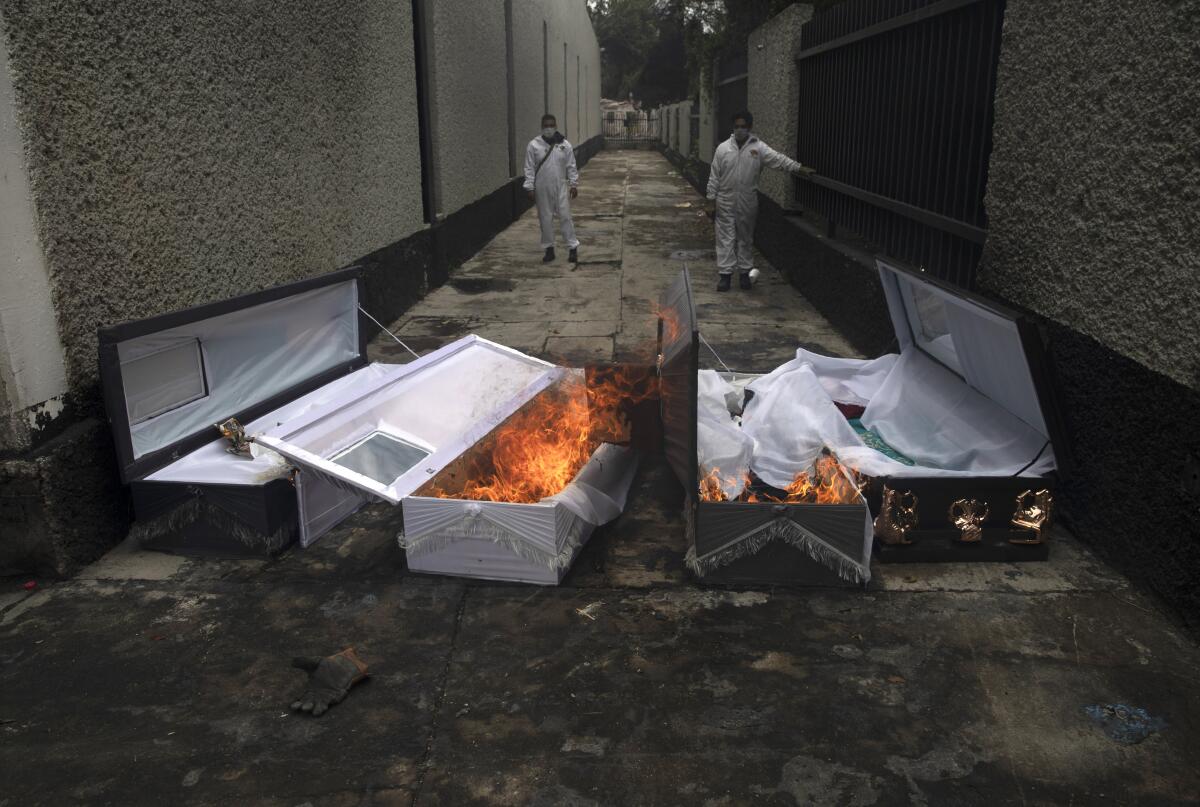

Latin America and the Caribbean, home to 8.4% of the global population but accounting for 30% of COVID-19 deaths, offer a striking example of that threat.

Relatively well-off countries such as Mexico, Brazil and Chile have earmarked billions of dollars for vaccine purchases, scrambling to cut bilateral deals with manufacturers. Yet they share borders or close economic links with poorer nations — including Bolivia, El Salvador and Nicaragua — that will have to wait for free vaccines from Covax.

“We all know that viruses don’t respect national borders,” Lusiani said. “People move. It’ll bounce back and create a public health problem even in really rich countries.”

China and Russia have also developed vaccines and are marketing the drugs — despite questions about their safety and efficacy — to countries worldwide for free or for a fraction of the cost of Pfizer’s and Moderna’s shots. Among China’s customers are Mexico and Indonesia, which is suffering one of Asia’s most severe outbreaks and has vowed to make vaccines free to all citizens.

It could be a while before U.S. efforts to develop coronavirus vaccines benefit the developing world. China and Russia are trying to fill the void.

Drugmaker AstraZeneca is currently conducting late-stage trials on a vaccine that holds special appeal in poorer countries because it does not require ultra-cold refrigeration like the Pfizer drugs, presenting fewer logistical challenges.

The company has pledged to sell most of its product to developing nations and at lower prices during the pandemic. But the bulk of those deals so far are with China and India, which have large domestic drug manufacturing industries.

India’s generic-drug industry, which makes most of the vaccines already in use around the world, has tapped funds from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and other sponsors to expand production facilities for COVID-19. Initially, at least, most of India’s production will be reserved for domestic use, with the government pledging to immunize as many as 300 million people by next September.

The country’s largest manufacturer, the Serum Institute of India, says it also plans to produce 200 million doses of vaccines from AstraZeneca and the U.S. company Novavax and sell them to Covax for about $3 per dose, just enough to cover its costs.

“In the context of a global panic, India’s manufacturing capacity is a great strength the world can rely upon,” said K. Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India.

“Every country has an obligation to protect its people, but when you are grabbing more vaccines than what you need, if you are hoarding it or using it to enhance your own political prestige and power, that is unacceptable in a pandemic. I would say it’s morally reprehensible when you look at the state of the world.”

Bengali reported from Singapore and Linthicum from Mexico City.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.