How secret deals could keep a COVID-19 drug out of reach for millions

The American pharmaceutical giant Gilead Sciences is coming under scrutiny for agreements that activists say will restrict global access to remdesivir, an experimental antiviral drug that has shown promise in treating COVID-19.

The Foster City, Calif.-based company has signed confidential licensing deals with nine pharmaceutical manufacturers — including seven in India — that would prevent the generic version of the drug from being distributed in dozens of countries, including the U.S., that account for nearly half the world’s population.

Activists and civil society organizations say the licenses allow Gilead to control the global supply of its patented drug even as the World Health Organization warns the COVID-19 pandemic is entering a “new and dangerous phase.”

Although the terms of the licenses have not been publicly disclosed, Gilead has said they allow for a cheaper, generic form of remdesivir to be distributed in 127 countries, including nearly all of the world’s poorest nations.

But the agreements exclude countries with some of the worst coronavirus outbreaks — including the U.S., Brazil, Russia, Britain and Peru — leading to allegations that Gilead aims to sell only its much costlier, name-brand version of the drug in middle-income and wealthy nations that are desperate for the treatment.

“These bilateral licenses … are highly restrictive in their application,” said Brook Baker, a professor of law at Northeastern University. “Gilead excluded these countries because they have commercial potential and because Gilead wants to reserve the right to prevent competition and charge higher prices.”

Gilead did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

The company has faced criticism for pricing remdesivir at $390 a vial for governments — or $2,340 per patient for a standard, five-day course — and $520 for U.S. insurance companies, or $3,120 per patient.

The company says the prices are fair when compared with the cost of a longer hospital stay. But critics contend that because Gilead received about $70 million in federal funds to develop the drug, the prices are unfairly high.

One of the Indian companies that has negotiated a license with Gilead, Hetero Labs, has said it will price its generic version at about $71 per vial — still out of reach for many patients in the developing world. A study conducted by Andrew Hill, a drug pricing specialist at the University of Liverpool, estimated that remdesevir could be made for just a few dollars per treatment course.

Remdesivir, originally designed to treat Ebola, has been the subject of intense interest since the National Institutes of Health reported in April that the drug shortened the average recovery time of a COVID-19 patient by four days in a clinical trial. The Food and Drug Administration has approved the drug for emergency use.

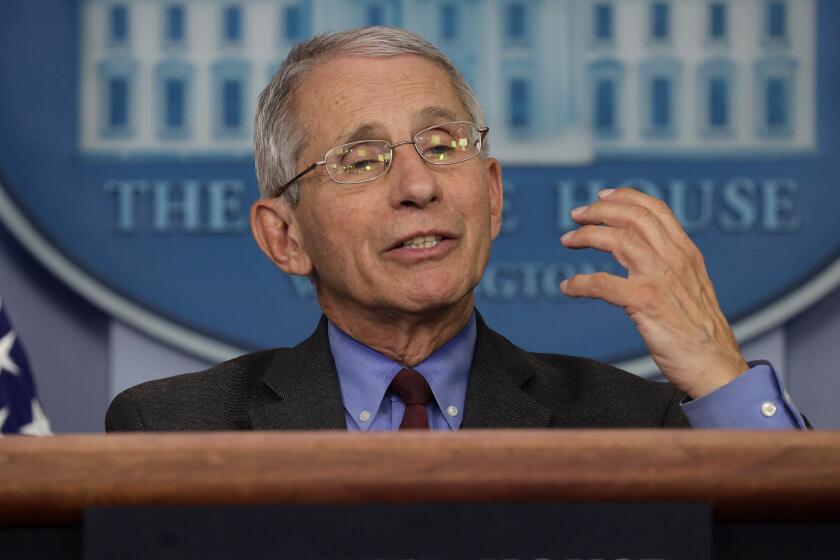

With a COVID-19 vaccine believed to be months away — at best — medical experts have identified remdesivir as one of the few effective treatments for a pandemic that has claimed more than half a million lives. Dr. Anthony Fauci, who heads the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, called the results of the clinical trial a “really quite important” milestone.

The drug helped some coronavirus patients recover faster. But it’s hardly everything we’d wished for.

This week the U.S. government announced it had bought up almost all 500,000 treatment courses that Gilead expects to produce through September. That leaves Gilead’s licenses with nine generic drug makers — including companies in Egypt and Pakistan — the best hope for patients in the rest of the world to access the drug.

India has the world’s largest generic-drug industry and manufactures some 80% of the drugs sold in the developing world. The country gained a reputation as “the pharmacy of the poor” by driving down the cost of anti-HIV treatment during the AIDS pandemic, thanks to heavy competition among domestic drug makers.

Experts said that by granting licenses to a limited number of companies that are authorized to sell only in certain markets, Gilead would retain control over the global price and marketing of the drug.

The licenses “are an attempt to contain the competition by creating an oligopoly,” said K.M. Gopakumar, legal advisor for the Third World Network, a think tank that focuses on the pharmaceutical industry. “Gilead not only retains the profitable markets like developed countries, but also eliminates the potential introduction of low-cost drugs into the American market.”

As the pandemic continues to rage in poor countries in Asia and Africa, there is growing concern about ensuring an equitable supply of treatment. In March, 150 civil society organizations, including the medical charity Doctors Without Borders, wrote to Gilead expressing concern over the company’s attempts to restrict access to remdesivir.

“If remdesivir is found to be effective and is approved, Gilead should not be allowed to enforce its patents nor claim any other types of exclusivities over remdesivir,” the group wrote. “No company should profiteer off this pandemic.”

Activists also point to another aspect of the licenses: Gilead doesn’t receive royalties, but only until another drug or a vaccine is approved to treat or prevent COVID-19. Once that occurs, although the size of the payments hasn’t been disclosed, “it is clear that such royalties will add to the price of remdesivir,” said Baker, the law professor.

Arguing that private companies have too much control over drug access, a 2016 panel convened by the United Nations secretary-general recommended expanding public funding of research and clinical trials and eliminating monopoly rights over drugs. Health experts say a global treaty is needed, similar to the tobacco control framework adopted at the World Health Organization in 2003 that created universal standards stating the dangers of tobacco and rules governing its production, sale and taxation.

But activists say the U.S., backed by major pharmaceutical companies, has stymied such a treaty for the research and production of drugs and vaccines.

“Though there are many COVID drugs and vaccines under development, there is no guarantee that there would be equitable access,” Gopakumar said. “The best way forward to create a legally binding global treaty.”

Krishnan is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.