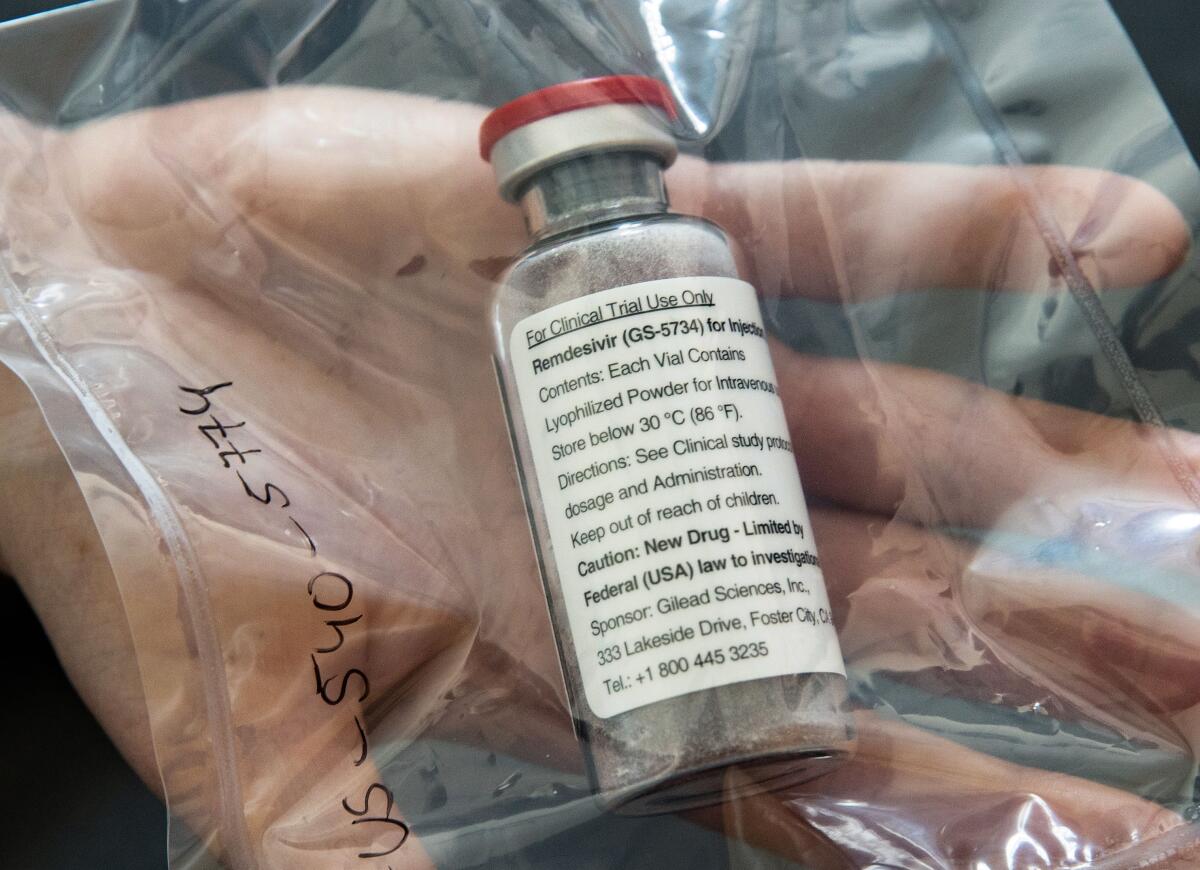

Remdesivir shows promise in preliminary coronavirus trial

A preliminary report on COVID-19 patients treated with the experimental drug remdesivir suggests that the antiviral medication may lower the risk of death in severely ill patients and improve the condition of patients relying on a range of devices for breathing assistance.

The safety and effectiveness of remdesivir as a treatment for coronavirus infection is being tested in clinical trials in the United States and around the world. Those studies will rigorously compare the drug against a variety of standard treatments to determine whether its benefits are real, and come without side effects that could put vulnerable patients in further danger.

The report published Friday in the New England Journal of Medicine is among the first to detail the results of remdesivir use in patients whose conditions were meticulously recorded and tracked for 28 days. Among the study’s 53 patients, three-quarters got a full 10-day course of the drug and the remainder took it for between five and 10 days.

Seven, or 13%, of the 53 patients died. That includes six of the 34 patients who were receiving mechanical ventilation or the support of a blood-circulating bypass device when the study began; the death rate in this more severely affected group was 18%.

Altogether, 68% of patients who got remdesivir saw improvements in their condition during the 28-day study window. Among the 30 patients whose oxygen was being supplied by mechanical ventilation, 17 (or 57%) were able to be withdrawn from the breathing machines by the end of the trial.

Significant improvement was also seen in three of four patients whose illnesses were so severe they had been placed on a bypass machine to filter, oxygenate and pump their blood.

All of those 20 patients who improved while on remdesivir were alive at the researchers’ last follow-up. Overall, six of the 53 patients remained hospitalized.

Remdesivir, a drug designed to disrupt or suppress a virus’ ability to replicate in the body, was provided under a “compassionate use” program that allows patients to try medications that aren’t yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration as long as the patients are very sick and have no treatment alternatives.

Some patients who have recovered from coronavirus infection are suffering lasting damage, including liver damage, heart damage and blood clotting problems.

The experimental medication was designed to treat patients infected with the virus that causes Ebola, but it was found to be less effective than other medications in treating that disease.

The authors of the New England Journal study — which was funded by the drug’s maker, Gilead Sciences — noted that the mortality rate seen in the 53 COVID-19 patients was lower than in other trials that tested a cocktail of the antiviral drugs, ritonavir and lopinavir.

For instance, a clinical trial of ritonavir and lopinavir conducted in 199 COVID-19 patients reported that 22% of them died over 28 days. But only one of those patients had been sick enough to require mechanical ventilation when they joined the trial.

In addition, the study’s subjects appeared far more likely to survive than patients who received a range of other treatments.

Chinese studies that tracked the progress of COVID-19 in patients sick enough to be admitted to intensive care units have reported death rates ranging from 17% to 78%.

“By way of comparison, the 13% mortality observed in this remdesivir compassionate-use cohort is noteworthy, considering the severity of disease in this patient population,” wrote the authors of the new study, who were from the U.S., Canada, Japan and countries in Europe.

Several groups of researchers are testing different methods to divert critically ill COVID-19 patients from needing ventilators in the first place.

Adverse events were seen in six of 10 patients who got remdesivir. In 12 patients — roughly a quarter or them — adverse events included severe problems such as multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, septic shock, acute kidney injury and low blood pressure.

Because of the trial design, the improvements seen in patients cannot be attributed directly to remdesivir. Nor is the drug necessarily responsible for adverse events observed in patients. Those issues of causation remain to be established by larger and more rigorous clinical trials.