After living in the U.S. for more than half a century, this Cuban activist may be deported

MIAMI — Ramón Saúl Sánchez was 12 when he hugged his family in Cuba goodbye and boarded a plane for Miami.

“Te amo mucho,” his mother told him, assuring him they would soon be reunited.

Sánchez was too upset to speak.

It was 1967, eight years since Fidel Castro had seized power. The family was sending Sánchez and his younger brother Luis to the United States as part of the Freedom Flights — a massive resettlement program for Cuban refugees — to avoid military conscription.

In Miami, relatives squeezed the boys into a three-bedroom apartment already crowded with other Cuban exiles. Sánchez enrolled in middle school, but he did not speak English and cried every day from homesickness.

As the years went by, he devoted himself to fighting the Cuban government from Miami, becoming one of the city’s most zealous anti-Castro activists and a motor-mouthed advocate for Cubans seeking refuge.

Increasingly, he wondered whether he would die before he could return to the island and see his family again in the countryside near Colón.

But now Sánchez faces a new problem as Cubans — who have long had a uniquely privileged status among immigrants as a result of U.S. opposition to communism — find themselves increasingly vulnerable to deportation.

After repeatedly being denied a green card, Sánchez has applied for political asylum — his last chance of remaining in the United States.

It is the place where he has spent the vast majority of his 65 years, where he earns a living as the project manager of a nonprofit housing company, where he runs a pro-democracy group, where he hosts a radio program, where he has married and divorced five times.

He still feels the ache of exile, but now he also wonders whether, for the second time in his life, he will be forced to leave his home.

“It’s like you have been in love with somebody all your life,” he said, “and suddenly that person says, ‘Get out of my life.’”

::

A few years after Sánchez arrived in Miami, he was working as a stock boy in a Cuban grocery store when a young man came in talking about overthrowing Castro.

Looking for a way home, Sánchez begged to be a part of the movement.

At 15, he joined the anti-Castro paramilitary group known as Alpha 66, training in the Everglades to learn the skills of guerrilla warfare. He had not yet finished 10th grade.

Like many Cuban exiles then, Sánchez had come to believe that armed struggle was the only way to remove Castro.

In that sense, his perspective was not so different from that of the U.S. government, which trained 1,400 Miami Cubans for the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961.

But after anti-Castro Cuban paramilitary groups began setting off bombs in the United States in the 1970s and assassinated an attache of the Cuban mission to the United Nations in New York in 1980, federal prosecutors took notice.

In the early 1980s, a federal grand jury subpoenaed Sánchez as part of an investigation into Omega 7, a violent paramilitary force. He denied being a member and refused to testify.

It’s like you have been in love with somebody all your life, and suddenly that person says, ‘Get out of my life.’

— Ramón Saúl Sánchez

Convicted of criminal contempt of court, he spent the next 4½ years in prison.

Sánchez said the grueling violence of prison life transformed his thinking about how best to liberate Cuba. Upon release in 1986, he renounced armed revolution and drove out to his old guerrilla training camp to preach the philosophy of nonviolence.

It was a hard sell, and many of his comrades thought he had effectively surrendered to Castro.

But Sánchez went on to become a key voice of moderation, emerging in the late 1990s as the ebullient, mustachioed leader of Movimiento Democracia, a nonprofit group that repackaged the old guard’s criticisms of Castro in the language of civil rights.

Some exiles dismissed him as a self-serving publicity hound as he kept popping up on street corners with a megaphone. Peppering his speeches with references to Mahatma Gandhi, Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., he led sit-ins and hunger strikes against the deportation of Cubans and “freedom flotillas” into Cuban territorial waters to memorialize Cuban migrants who died trying to leave Cuba.

In 2000, he waded into the high-pitched international custody battle over Elián González, the young boy plucked from the Florida Straits after his mother drowned while they were trying to flee Cuba. Elián was placed with relatives in Miami, and Sánchez led round-the-clock vigils and human chains outside the family’s Miami home in an effort to block him from being sent back to his father on the island.

After five months of protests, armed federal agents entered the house, seized Elián and sent him back.

Even as he eschewed violence, Sánchez continued to antagonize U.S. officials.

In 2001, when he entered Cuban waters for another memorial service, he was indicted on federal charges of conspiracy for violating a 1996 proclamation by President Clinton aimed at regulating such protests to prevent the U.S. from being drawn into an international crisis. Sánchez, who insisted he had the right under international law to make the journey, was acquitted by a federal jury.

“I’m an activist in favor of the freedom of Cuba,” he said recently. “Unfortunately, if you struggle against dictatorships — and policies in Washington are to keep the status quo — you’re going to run into problems.”

::

Sánchez always considered himself, first and foremost, a Cuban.

Living in the United States under a special refugee status, he long believed that becoming a permanent U.S. resident would undermine his criticism of Castro and betray his cause.

His brother Luis, who had stayed away from activism, received a green card long ago. But Sánchez only applied for one after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, when the government began requiring yearly renewal of work permits.

Years went by without a decision, but Sánchez was not worried. The 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act virtually guaranteed a path to citizenship for any Cuban who fled the island.

The 1995 “wet foot, dry foot” policy dialed that back a notch by turning away Cubans intercepted at sea — before they could touch U.S. soil.

But in 2016, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services denied Sánchez’s application and ordered him to leave the country “as soon as possible.”

“I would probably face the firing squad,” Sánchez said, considering his fate if forcibly returned to Cuba. “If I’m lucky, they will put me in prison for a very long time.”

He was able to continue renewing his work permit and driver’s license as he appealed. But he was unnerved, fearing that he was being sacrificed in the Obama administration’s effort to improve diplomatic relations with the Cuban government.

Days before leaving office in early 2017, President Obama rescinded “wet foot, dry foot.” In turn, Cuba agreed to accept returned Cuban migrants, which it had rarely done before.

Things did not get any better for Sánchez when President Trump took office.

Trump promised to restore a hard-line approach in dealing with the Cuban government, but his marquee campaign pledge was a crackdown on immigration, starting with immigrants with criminal records. Cubans were not exempt.

In the fiscal year ending in September, 1,179 Cubans were deported, up from 64 in the final year of the Obama administration. Thousands more asylum seekers now find themselves stuck in Mexico or in U.S. detention centers with little chance of being allowed to live freely in the United States.

“Why is he doing this to us?” Sánchez said of Trump. “If you understand that this is a dictatorship that oppresses people, yet on the other hand increasingly denies political asylum to people escaping the island, there’s a contradiction.”

Last summer, immigration officials denied Sánchez’s appeal, sending him a 17-page document, citing his role in the freedom flotillas and the Elián González protests as well as his refusal to testify against Omega 7.

It also listed some criminal convictions, including a felony at the age of 18 for keeping a licensed gun under his seat of a convertible Mustang rather than in the glove compartment.

Sánchez and his legal team argue that the government’s conclusions are based in large part on lies from criminals and that his convictions are not for crimes of “moral turpitude” that should disqualify him from obtaining a green card.

Again, Sánchez appealed. Again, his appeal was denied.

::

Now a gray-haired elder statesman of Miami’s Cuban exile community, Sánchez increasingly finds himself wondering where he would choose to live if Cuba’s government fell.

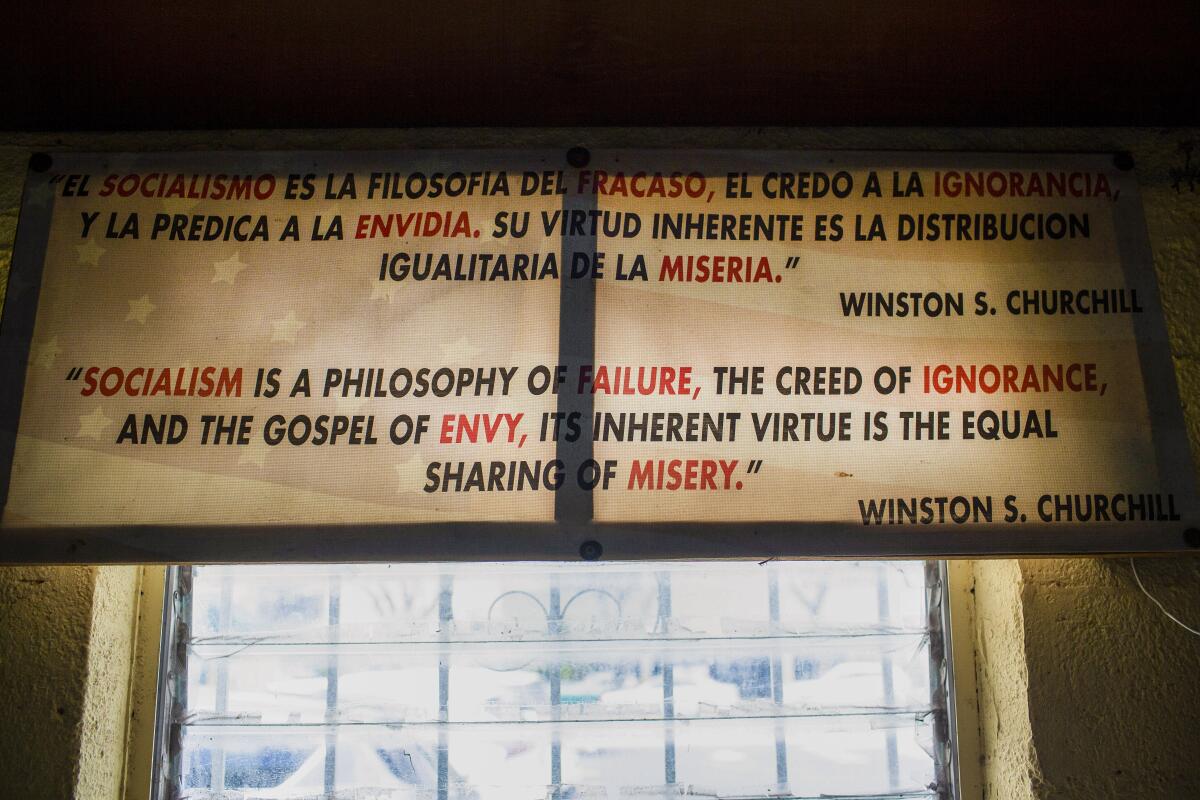

“I didn’t use to ask that question,” he said on a recent afternoon, surrounded by old protest banners and portraits of Cuba’s pre-revolutionary leaders inside his tiny, run-down Movimiento Democracia headquarters. “As time goes by, I ask that question.”

His mother and grandmother are long dead, but two brothers and an uncle still live on the island.

His main companion now is his girlfriend, who left Cuba for Miami nine years ago and, at 33, is about half his age. He happily shares her photo —she is modelesque with long glossy hair — but not her name, fearing their relationship would cause her problems with the Cuban government if she returns to visit her family.

Why is he doing this to us?

— Ramón Saúl Sánchez

Though his chest swells and his hands dance as he rails against the Cuban government and U.S. foreign policy, he becomes more hesitant as he considers the toll of his commitment to anti-Castro activism on his personal life. Less than a year after his first marriage, he was hauled off to prison. Even after he rejected armed revolution, he was consumed with meetings, protests and flotillas.

“When we go out in a flotilla, we don’t know if we’re going to come back,” he said. “To the other half of you that stays here, it’s very hard.”

One of his biggest regrets is that he never became a father.

He said he kept postponing those plans for a time when his struggle to overthrow Castro would be over. Now his immigration fight has complicated hopes of having a child with his girlfriend.

“I can get deported tomorrow,” he said. “If I have a child, he will grow without me.”

Earlier this year, after 3G technology came to the island, Sánchez sent one of his two younger brothers in Cuba a cellphone.

Holding up his phone’s video camera, Sánchez showed him the streets of Miami, starting at Versailles, the landmark Cuban restaurant on Little Havana’s Calle Ocho, then driving east toward the gleaming skyscrapers of downtown.

On the way, he stopped to show him Freedom Tower, the grand 1920s-era building where the federal government processed Sánchez and hundreds of thousands of other Cuban refugees fleeing the island.

“This is where we started our life in America,” he told his brother.

Then he watched his brother walk the streets of Colón, pointing out the simple one-story white house where Sánchez once lived, the statues of lions in the main square, the same puesto stand that served hamburgers when they were children.

The paint had faded on many of the old colonial buildings, and the streets were cracked and riddled with potholes. But just for a few minutes, he was transported to the streets he had spent decades dreaming of walking.

When Sánchez put down his phone, tears streamed down his cheeks as he walked from his sedan into his Miami apartment.

::

Sánchez still broadcasts his take on Cuban politics on his weekly Miami AM radio show, “Desafio,” which means “challenge.” And nearly every hour, he tweets rapid-fire critiques of the Cuban government and its allies.

But when it comes to the rapid escalation of Cuban deportations, both he and Miami’s Cuban community are uncharacteristically reserved.

In 1982, exiles in Miami faced off against riot police after the first deportation of a Cuban asylum seeker in the Castro era. In recent years, there have been few protests — even after Immigration and Customs Enforcement packed a charter flight to Havana in August with 120 Cubans, the most ever deported at once.

“The Cuban people are tired,” Sánchez said. “Time has passed. Many no longer have faith that we, on our own, can change the regime.”

As for his own legal fight to stay in the United States, he dismissed it as a “total distraction” from his struggle against Cuba’s government.

Though his attorney said he is confident Sánchez will be allowed to stay, Sánchez said he is not so sure.

Avoiding a high-profile public campaign could be a calculated effort to avoid antagonizing the authorities who will decide his fate or a show of faith that Trump will ultimately come to his rescue.

But Sánchez also believes that defending Cuban asylum seekers has become trickier at a time when immigration has become such a huge national political issue. He worries that criticizing the Trump administration too harshly on immigration could alienate Americans who favor a clampdown on immigrants, as well as detract from his criticism of Cuban leaders.

“I don’t want deportation to be a final, hostile chapter of my presence here,” he said. “I will leave grateful I was able to live most of my life in this society freely. And I say that so the Cuban people will hear.”

Still, Sánchez seems to recognize that his movement is on the verge of becoming history as the older generations of Cuban exiles die off and the communist government remains in power in Havana.

One evening at the Movimiento Democracia headquarters, just before turning off the flickering fluorescent lights, Sánchez explained that he and his band have plans for their shabby center.

After they clear up the clutter of campaign props — old protest placards and memorial shrines to Cubans who died trying to flee the island litter the floor — they plan to install a new floor and repaint the faded stucco exterior in the hope of luring tourists.

“We’re going to turn it into a little museum of the Cuban plight,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.