A rich history of pre-genocide Armenia hides in family heirlooms and handwritten notes

ATHENS — When the tightly knotted white and blue handkerchief was untied, it revealed a small handful of dirt from a distant time.

A soldier, rushing to gather whatever spare belongings he could carry, was fleeing to board a boat on the Gallipoli Peninsula. It was a boat of survival, taking him and other Armenians away from the Ottoman Empire and the campaign of genocide it was waging against them and other ethnic minorities. As he left, he knelt in the garden of his home and scooped up this bit of dirt. Carried in his pocket, it was a literal piece of the homeland to which he’d never return.

This was nearly a century ago.

The handkerchief has since been handed down for three generations. On a bright December day in Athens, it was one of several hundred objects brought by members of the Armenian diaspora in Greece to be added to what, until recently, had been only a limited historical record of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire before and during the genocide.

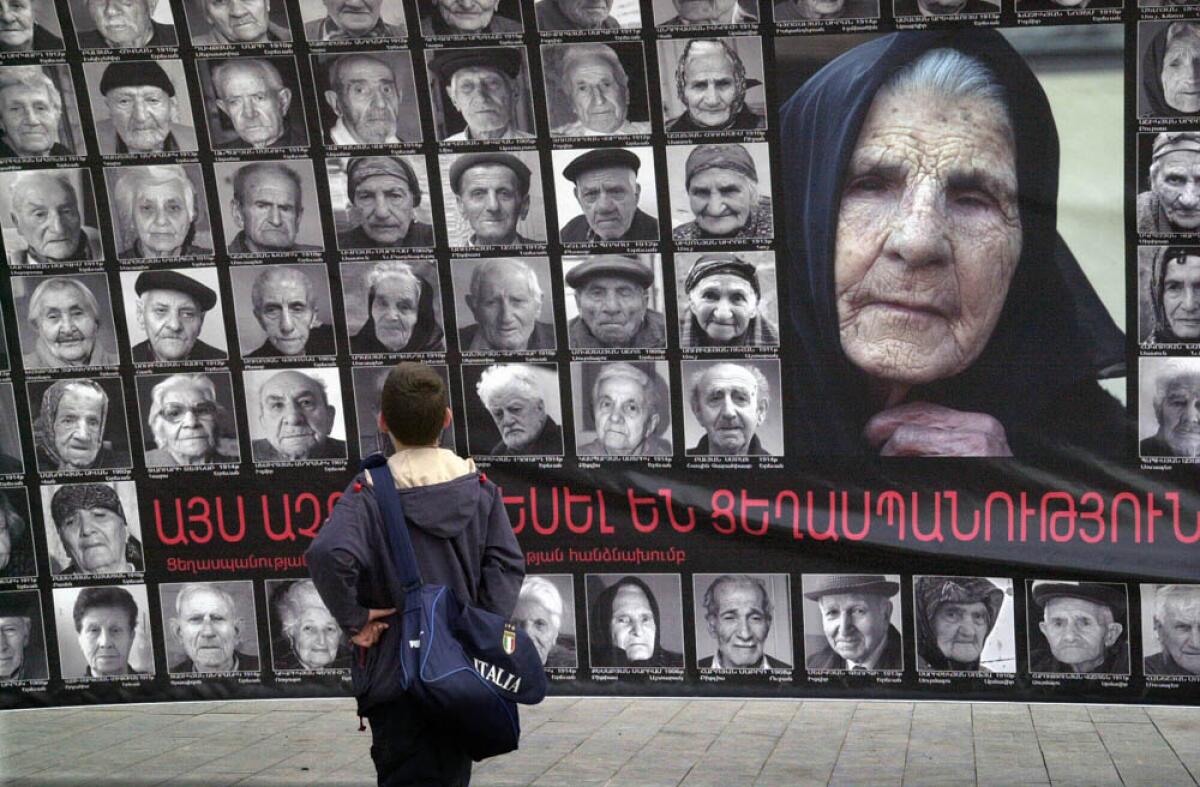

Taking place mostly between 1915 and 1923, the genocide killed an estimated 1.5 million Armenians and dispersed many more to adopted homes around the world, from Lebanon to Syria to France to the United States. Turkey says the death toll was much smaller and describes the violence as a civil war, not genocide.

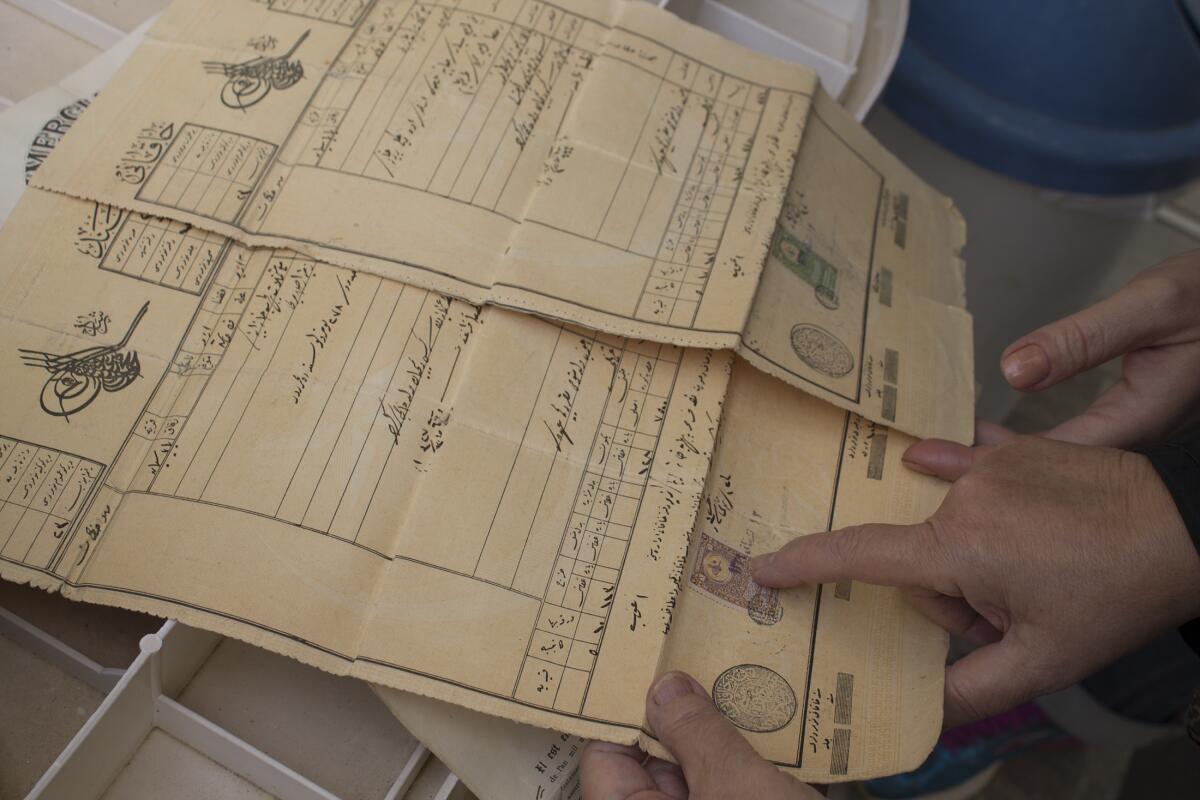

A Christian ethnic minority, Armenians lived throughout the Ottoman Empire among Muslim Turks and Kurds but were primarily concentrated in what is now eastern Turkey and western Armenia. Though many historical records and items document the empire around the turn of the century, little of it is told in the language, or from the perspective, of the Armenians. For Vahé Tachjian and Elke Hartmann, a married team of Ottoman scholars based in Berlin, this is problematic.

“Armenian sources of course exist, and they are very rich,” Tachjian said. But unlike formal or official historical items, much of the story of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire was either destroyed in the chaos of the deportations and massacres or never properly recorded in the first place. What remains are the unintentional markers of history passed through generations: handwritten accounts of local villages, photos mailed to family members abroad, embroidered garments, a handful of dirt tied in a handkerchief.

“Our objective was to give another value to these sources,” Tachjian said.

The project started in 2010. After scouring libraries and archives for their limited Armenian-language resources, Tachjian and Hartmann found a vein of material in what were known as “houshamadyan,” handwritten and self-published memory books that describe — sometimes simply, other times in great detail — the villages and ancestral lands Armenians were forced to flee. In 2011, they began posting information from these documents on their website, which they named Houshamadyan.

Almost as soon as the site launched, they began receiving emails from around the world written by the descendants of Armenians offering their own records. Surprised by this outpouring, Tachjian and Hartmann, both of whom have Armenian heritage, redirected their focus from formal archives to the heirlooms of the Armenian diaspora.

“There were so many treasures in family houses, family closets,” Tachjian said.

To document these materials and the handed-down history they carry, Tachjian, Hartmann and a small team of part-time collaborators began staging workshops around the world where people could bring their family heirlooms and documents to be added to the collection.

Funded by private donors and foundations, these workshops have been held in Istanbul, Beirut, Paris, Los Angeles and Glendale, all destinations for the Armenian diaspora, and Tachjian says each place offers its own unique angle on this history.

The most recent workshop was in Athens, where a small minority of Armenians has lived since thousands arrived as refugees in the early 1920s. A mile south of the Acropolis, in the back room of a primary school that doubles as an Armenian cultural center, about a dozen descendants trickled in on a Saturday afternoon. Mostly in their 50s and 60s, they came carrying shopping bags of photos and carefully wrapped books, textiles and pieces of jewelry. Speaking fluent Armenian in his clipped baritone, Tachjian interviewed each person about their family’s history, the heirlooms they’d kept and any memories that had been passed down about the Ottoman villages and towns from which their families fled.

One woman, Vicky Khatchadurian, showed him silver utensils and a woven rug that her grandmother brought from Constantinople (now Istanbul) to the Greek island of Cephalonia, items that would go on to serve as her grandmother’s marriage dowry. She “was a lucky one,” Khatchadurian said. “She had the opportunity to survive.”

Sitting on the tile floor nearby, Arshaluis Sapritchian, an Armenian language teacher at the school, was slowly turning through a handwritten notebook as each page was photographed. It was the autobiography of her grandfather, written in 1986 when he was 80 years old, beginning with his early years living in exile as the genocide started and much of his family was lost.

He wrote how later he was unexpectedly reunited with his mother and they became refugees in Greece, moving from temporary settlement to temporary settlement with other Armenians who’d fled. Sapritchian compares it to the way the Greek government is dealing with its more recent influx of refugees from places including Syria and Afghanistan.

“Today when I see what’s happening with refugees, it’s tearing my heart because it’s the same thing that was happening with my grandfather,” she said. It was a story he never told his grandchildren until writing it down in this notebook. “He wanted us to grow up in happiness. He didn’t want us to bear all this burden he had,” Sapritchian said. “But at age 80, he decided he needed to share this burden.”

Later, Silva Avedisian unfolded a delicate white embroidery and asked for help deciphering the lettering stitched into its corners. The embroidery was made by her grandmother, who escaped from a concentration camp at 18 with her dying mother during a storm and had to bury her, alone, with her bare hands. The lettering, a translator explained, read, “God give you good health.”

By the end of the day, hundreds of items had been shared and photographed, and Tachjian had nearly filled his notepad with stories and family histories.

People who were forced into exile or who fled on boats to places like Greece often carried very little with them, and the things they were able to transport became, over time, vaunted relics — the single earring one woman’s grandmother grabbed as she dashed out of a burning house, a book of prayers that was read by a family every night, the deed entrusted to a 6-year-old boy fleeing Ankara with the hope that one day the Turkish government would return his family’s land. “Sometimes it’s the last connection for these families with their identity,” Tachjian said.

For others who left before the genocide, particularly those who went to the U.S. as migrant workers in Massachusetts, Michigan or the farms of California’s Central Valley, the threads of history are thicker. Letters and photographs flowed back and forth between family members, and sometimes this news from one’s home village would become the last documentation of a place and a people wiped off the map. And because of the relative wealth in the U.S., more of the houshamadyan memoirs of these people were able to be published, further adding to the historical record. “Geography is very important,” Tachjian said.

He estimates that the Houshamadyan project has collected more than 30,000 photographs from across the diaspora, as well as a variety of more quotidian documents such as recipes, school rolls and musically annotated hymns that were sung in some of the first Christian churches. These scattered relics have become a new kind of archive for an overlooked history. In addition to publishing various manuscripts and photographs from family collections, affiliated academics have used the website to publish their own research on pre-genocide life, often pulling from Houshamadyan’s online library. The website’s resources are even being integrated into university classes in Turkey, where the genocide is officially denied.

Hartmann, the project’s co-founder and a substitute professor of Turkish studies at the University of Hamburg, says that for decades Ottoman history has been seen simply as Turkish history, erasing all other populations from the picture. “This is slowly, slowly changing,” she said. “There’s an interest in seeing the Ottoman Empire in its multitude.”

But at the same time, the connections to this pre-genocide history are fading as family members age. “Many things have already disappeared,” Tachjian said.

The Rev. Vicken Cholakian, head pastor of the Armenian Evangelical Church of Greece, says there’s a danger that younger generations will lose interest in understanding this part of their history. He worries that stories of the genocide and the struggles afterward have overtaken the narrative of the Armenians and that younger generations would rather look to the future than to what can seem a wholly dark past. “It has become too central,” Cholakian said. “We should not repeat it so much to our young people that we don’t have anything else to say.”

Tachjian and Hartmann argue that the history being retold through the Houshamadyan project is representative of a broader spectrum of Armenian history — a time before the darkness. Not just what was lost but what existed, in all its richness.

Cholakian says this is the point of houshamadyan, the memoirs and histories that survivors wrote about their villages and lives.

“They hoped the next generation would read it,” he said. “Who will read it next?”

Berg is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.