A Texas Ranger got a prolific serial killer to talk. This is how

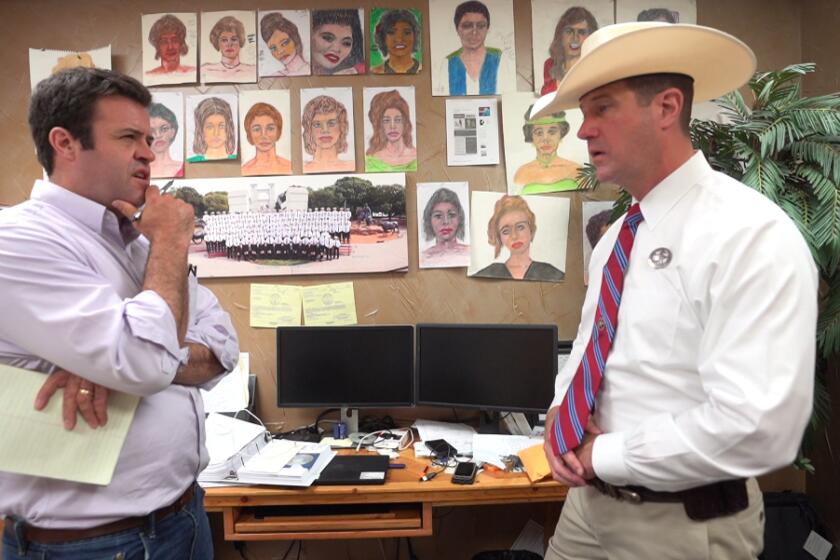

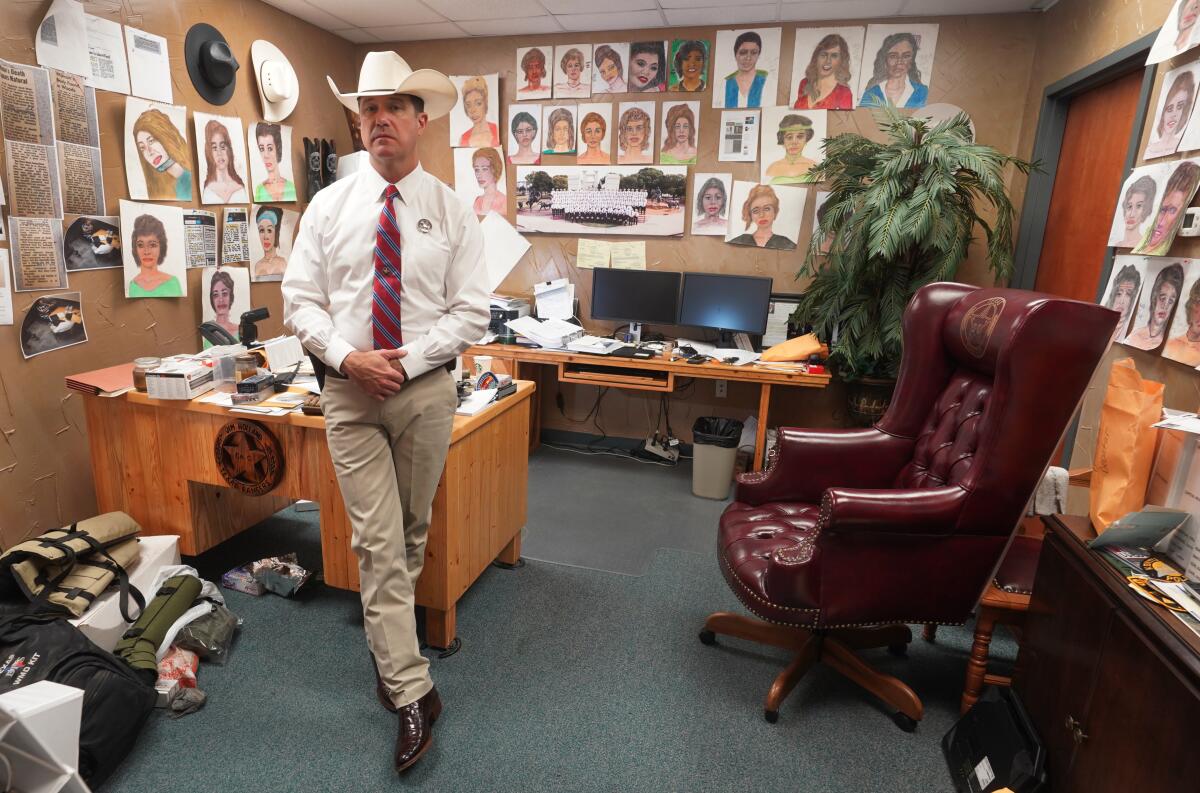

DECATUR, Texas — Texas Ranger James Holland each day enters his windowless, cricket-infested office, flips on fluorescent lights and is confronted by spectral visages staring back at him.

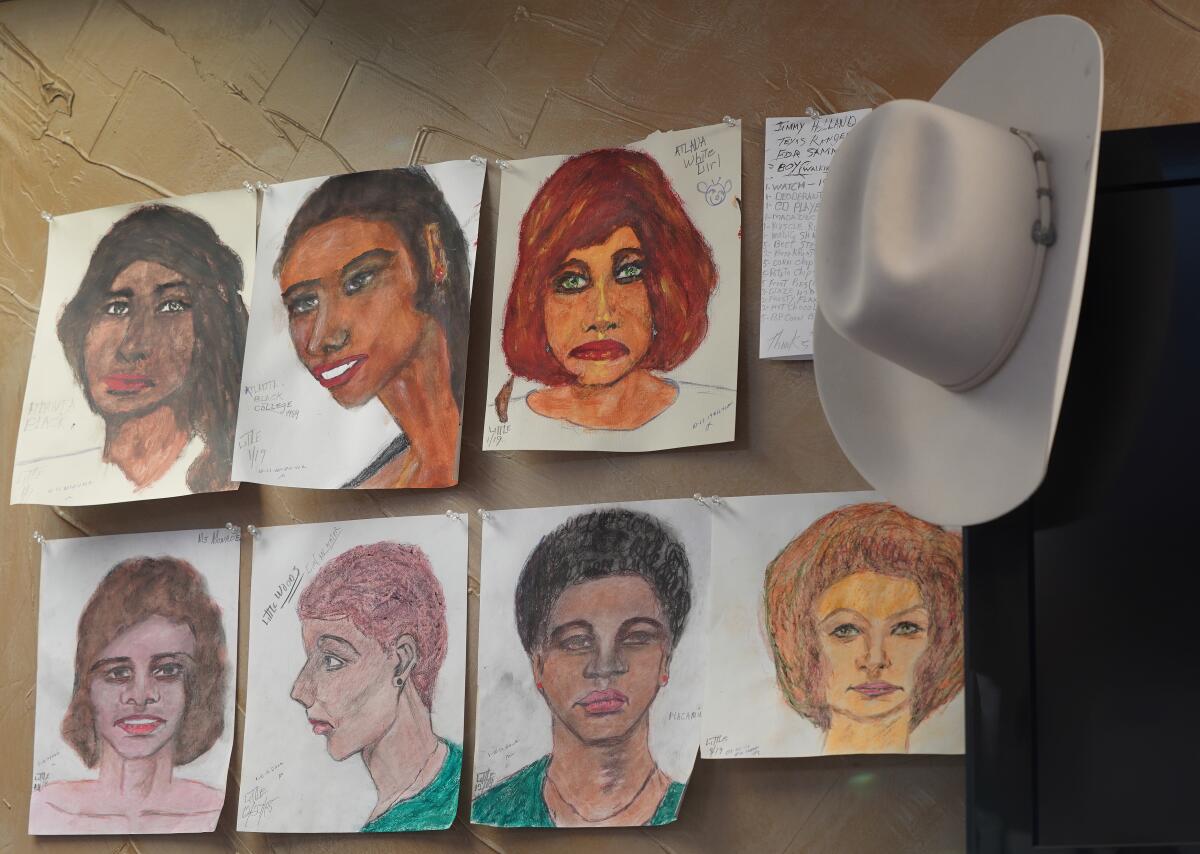

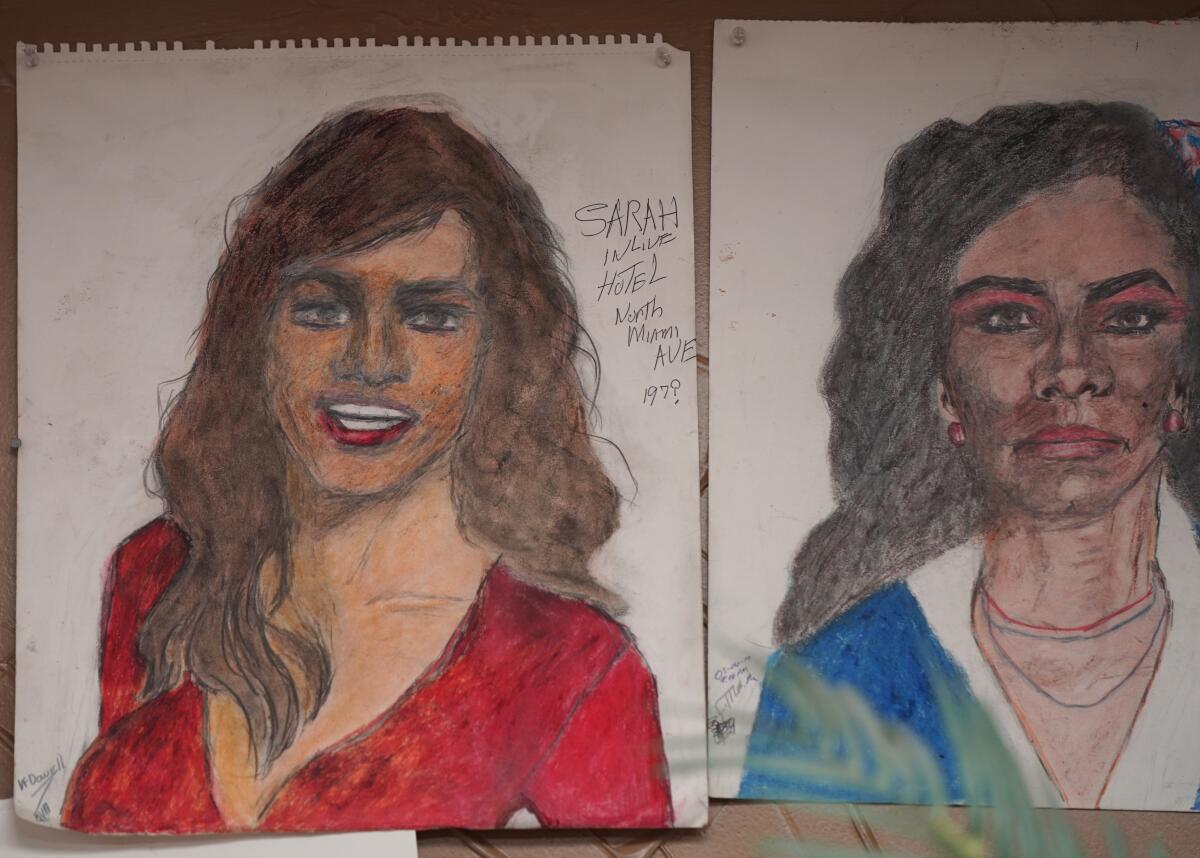

Holland lined the walls with dozens of haunting portraits of women, rendered from memory by their killer. The macabre gallery initially served as an investigative tool to help Holland keep straight a serial murderer’s myriad confessions.

Column One

Column One is a showcase for compelling storytelling from Los

Angeles Times.

The women appear in vibrant colors, with unique features — a bob haircut, lush lips, narrow nose, mournful eyes. Some pictures carry inscriptions: “Tampa Dope Girl,” “New Orleans Sarah Left in Field 1973 April,” “Akron Left in Woods 1990.”

Recently, the portraits have taken on a more haunting purpose, reminders that Holland is running out of time to put names to more of their faces.

He’s already found justice for some. Where a string of detectives had failed to crack Samuel Little, a pugilistic California prison inmate serving a life sentence for three brutal homicides in Los Angeles, the soft-spoken Holland managed to unlock a killer’s darkest secrets. In 650 hours of interviews over 16 months, Little confided to the detective he had strangled 93 women during a 40-year nomadic rampage from Florida to California, a tally that ranks him among the nation’s most prolific serial killers.

Holland, who wears a Stetson and cowboy boots and carries an ivory-handled .45-caliber pistol, concedes their conversations weren’t so much interrogations as meandering conversations over grits, Dr. Pepper and Braum’s milkshakes. He has said whatever was required to keep Little talking.

“You are giving me a heart attack today,” Holland told Little last September when the killer seemed likely to quit confessing. “I still love you, brother.”

“Thank you, Jimmy.”

“Sammy, brother, for the record, me and you have been through hell over the last five and a half months.”

“We ain’t giving up, Jimmy.”

Then, as he often does, Holland played to Little’s ego, letting him think he was the one in control.

“I know you are a powerful man,” Holland said, “a powerful man in the mind.”

“If you think so,” Little said, laughing.

Confirming Little’s claims has required a nationwide effort by Texas Rangers, FBI analysts and detectives to unravel mysteries in reverse — from confession to corpse.

Modern forensics played no role. The inquiries came down to shoe-leather police work: interrogation and digging through dusty files for clues, like a Western Union money gram from 1982, a witness who spotted a yellow Eldorado, a prostitute’s last meal of carrots.

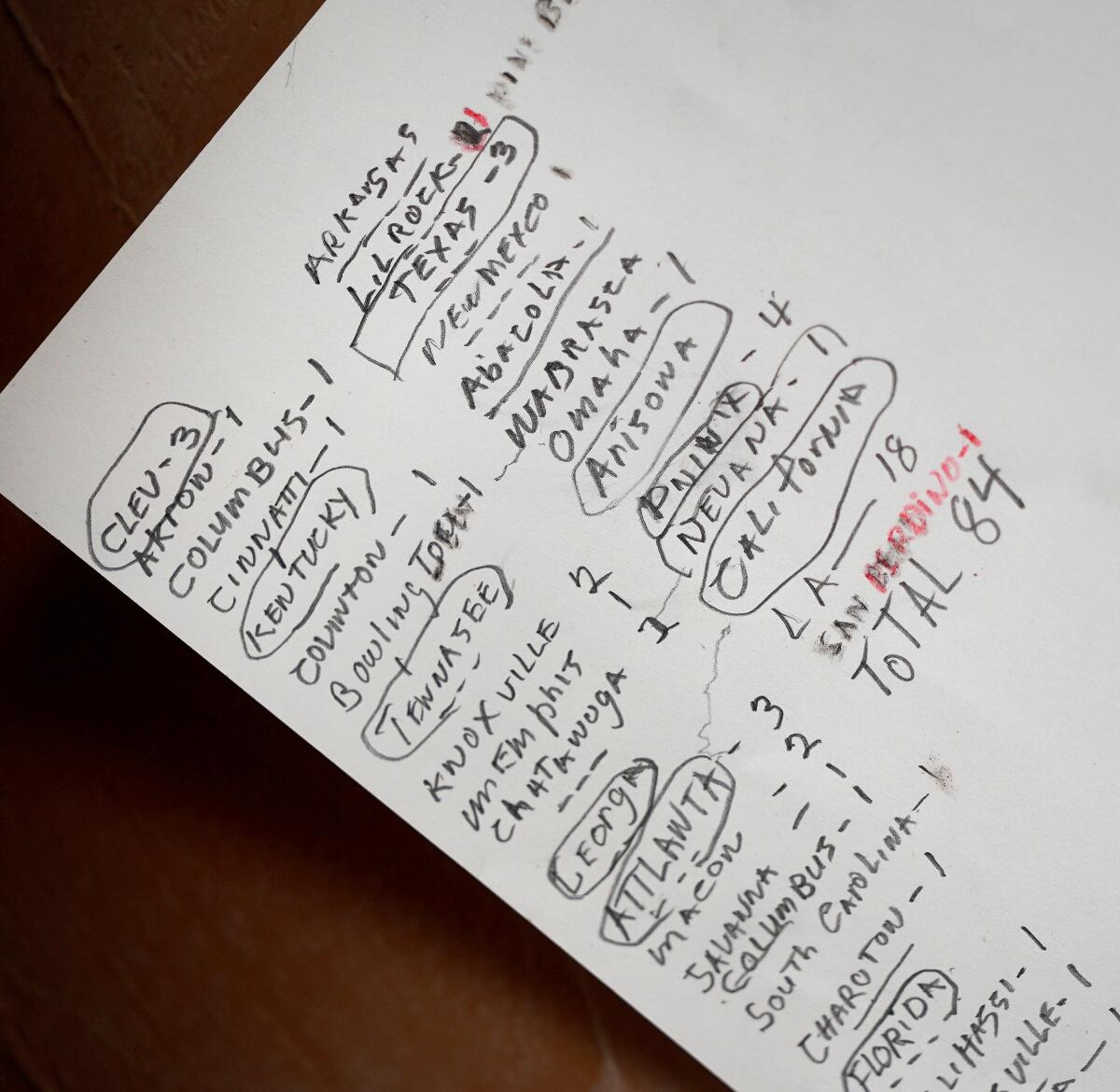

By his count, Holland and his team have confirmed 57 of Little’s 93 confessions, not including 21 in Southern California (he has left those to local police and prosecutors, and they declined to discuss their investigations. Little has admitted to killing the three women he was convicted of murdering in Los Angeles).

Little’s once-photographic memory is deteriorating, and Holland fears the 79-year-old killer won’t be able to identify a woman’s photograph, recall a detail or sketch an accurate portrait of the 15 or so victims the ranger has yet to name. Holland can sense he is losing his strongest connection to the women keeping unblinking vigil from his walls.

“Samuel Little has given me a massive gift, a gift to bring closure to victims’ families who have gone years without knowing what really happened to their loved ones,” said Holland, sitting under the portraits. “I have a responsibility. It is a big one. I feel it. I have to run with this and take it wherever it goes, do whatever it takes. And we know time is slipping away.”

::

Blue-eyed and square-jawed, with the tall and lean body of the college football player he once was, Holland grew up in suburban Chicago. In 1995, he became a state trooper with the Texas Department of Public Safety. Twelve years later, he joined the Texas Rangers, a storied agency of about 130 detectives who handle the state’s most serious offenses.

When he investigated his second homicide and persuaded a serial killer to take him to a hidden corpse, Holland found his calling. Through experience and study, he learned how best to approach sociopaths and psychopaths, becoming a serial killer whisperer of sorts.

He first heard about Little in December 2017 while teaching interrogation techniques at a police conference in Tampa, where he was approached by a Florida detective who wanted tips on how to interrogate Little, whom he suspected in one of his cases. The detective explained Little had spent his life traveling coast to coast and likely committed many homicides.

Little was convicted in 2014 of strangling three women in Los Angeles in the 1980s and sentenced to life in prison. L.A. officials speculated that Little may have killed as many as 40 people, and police nationwide were searching for his potential victims.

With the blessing of the Florida detective, whose case would turn out not to be connected to Little, Holland began digging into the killer. He sought help from analysts at the FBI’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program.

The analysts said that Little, whose real name was Samuel McDowell, had a lengthy criminal record and had spent significant time in Texas. They found 12 potential victims there. One, in particular, seemed to have the most potential: a prostitute slain in 1994 in Odessa. Like Little’s L.A. victims, she had been strangled and left partially clothed. Police records showed Little had been in the area around the time of the killing.

There is a maxim about serial killers — they only talk when they are ready. Perhaps Little was ready, thought Holland. Little had run out of appeals, and was battling a heart problem and diabetes. Immutable life sentences and one’s mortality are among the strongest of motivations to confess.

In May 2018, Holland and FBI analysts Christie Palazzolo and Angela Williamson flew to California. They first met with L.A. homicide detectives, who impressed Holland with their thorough work on the investigation.

The detectives said that Little despised them, and Holland was free to use that to his advantage. The detectives also said that Little hated being called a rapist, though his semen was found on the clothing of two victims and prosecutors labeled him a sexual predator.

Perhaps, Holland thought, Little saw a distinction between rape and becoming aroused during a strangling. That was something he might be able to work with.

‘It was like drugs. I came to like it.’

— Samuel Little, on his first killing

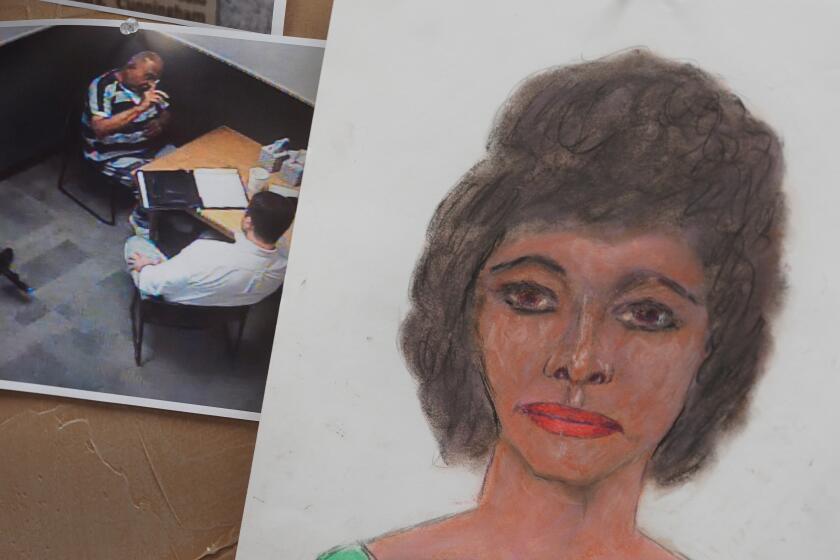

At 10:21 a.m. on May 17, with the FBI analysts listening in from another room at the prison in Lancaster, Little was rolled in a wheelchair into a cinder-block office and took a seat across a table from Holland.

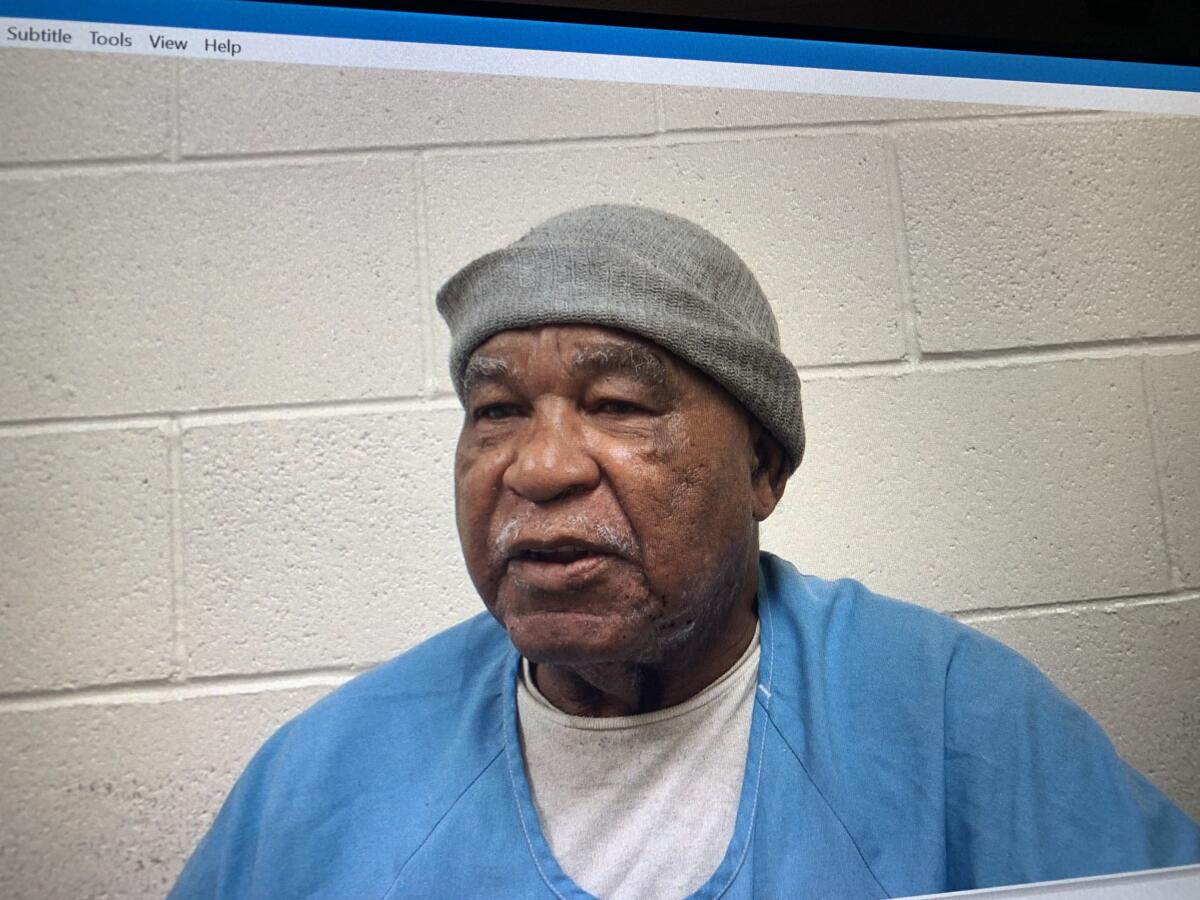

With a gray beanie covering his bald head, Little had a pockmarked face and deep-set eyes. He looked worn out, though he maintained the outlines of the street boxer he once was, with a barrel chest, knotty shoulders and thick arms. One feature immediately drew Holland’s focus: Little’s hands, his weapons, were the size of shovels.

Holland introduced himself. Little immediately demanded to know what the detective wanted.

“Just to visit for a little bit,” Holland said.

According to Holland and an audiotape of the interrogation, Little shook his head, saying he would never help law enforcement because he had been convicted “on lies and fake evidence.” Holland folded his hands on his lap as Little grew more riled, trashing L.A. police, prosecutors and the criminal justice system. Little’s syntax was snarled, and his accent a jumble of Southern drawl and Midwestern nasal that would confound FBI analysts and police but never Holland.

The ranger didn’t dispute Little’s assessment of L.A. authorities and said he didn’t think Little was a rapist, which seemed to please the killer. Trying to build rapport, Holland said he had heard Little was an artist (a 1976 newspaper story described him painting a mural in jail) and a boxer. Holland brought up college football. But Little just wanted to rag on L.A. police.

Then, a connection. What, Holland asked, should he call him? Most people called him Sam, Little said, but his mother and sister had called him “Sammy.” Holland said he was James to most people, but his mother called him “Jimmy.” Soon they were Sammy and Jimmy.

Holland asked about Little’s travels, wondering whether he had been to Midland and Odessa, neighboring cities in west Texas.

Little said he had never visited Midland, but he had been to Odessa.

The ranger felt a jolt. Little could have denied having been to west Texas. Holland sensed he was on the right path.

Little said that if he told Holland everything he had done, he would get the death penalty. On the fly, Holland promised to bring assurances from prosecutors that Little would not get a lethal injection if he spoke truthfully about Texas homicides.

Holland promised that if Little was honest, and he could verify his stories, he would tell the world “that Samuel Little is not a rapist.”

“You are right there,” Little replied.

“Samuel Little is not a murderer. I will say that too.”

Little nodded.

“Has Samuel Little killed people? Yeah, come on, we both know that,” Holland said. “The question is, does Samuel Little want to talk about those killings, and does he want to define what really happened?”

Little studied the ranger.

“Hookers is all you are going to find,” he said, finally.

Holland could tell the killer was testing him. Holland shrugged. “Do you see me tearing up?”

Little paused and then admitted he had killed three women in Texas, including a prostitute in Odessa. He had strangled her and left her in a vacant lot. It all matched the reports of the slaying in a 4-inch-thick dossier about Little on the desk in front of Holland.

Little provided the outlines of two other stranglings in Texas (neither on the list of 12 potential homicides). The killer blew Holland’s mind when he said he had stopped counting his homicides at 84. He said he was sure there were more.

His first strangling, he said, was of a woman with strawberry-blond hair on Dec. 31, 1970, in Miami. “It was like drugs,” he said. “I came to like it.”

Little also detailed his final homicide — a woman strangled in 2005 in a Mississippi town where Elvis Presley had once had a home.

When the interview was over 2 1/2 hours later, and Little was wheeled out of the room, Holland was a tangle of emotions. He was elated but apprehensive; he knew how much work lay ahead.

‘Confessions are great. But nothing means anything until we prove these all up.’

— Texas Ranger James Holland

That night, Holland and the analysts ordered Greek food but couldn’t eat because they were so hyped up. As Holland juggled phone calls with his bosses and a Texas prosecutor, an analyst found a news story that matched Little’s description of his final murder — that of Nancy Carol Stevens, 46, in Tupelo, Presley’s Mississippi birthplace.

“That really hit us,” Holland said. “So we took something of a blood oath: ‘Confessions are great. But nothing means anything until we prove these all up.’”

Holland persuaded the Texas prosecutor to send him the letter pledging not to seek the death penalty. He handed it to Little the next morning. The killer smiled. He insisted that Holland take a photograph of him holding the letter.

Over the next four hours, Little confessed to 17 additional slayings. He said his victims were almost all prostitutes, drug addicts or those he didn’t think would be missed.

Pressed about his life story, Little traced the urge to kill to his youth. He said he got his first erection in kindergarten when he watched his teacher touch her neck. Later in grade school, he dreamed of killing a girl who stroked her neck while teasing him.

At 15, he was flipping through a true crime magazine when he came across a photo spread depicting a strangled 18-year-old. He pinned it to his wall. “She had a beautiful neck.”

Little said he had been married once and had two longtime girlfriends who had followed him on the travels. He never killed anyone he loved and had made a conscious effort not to look at their necks.

“Did you have any favorite victims?” Holland asked.

“They are all my favorites,” Little replied. “They all belong to you.”

::

On Sept. 24, 2018, Holland brought Little back to Texas in a ranger plane. The flight had gone exceedingly well. Little recalled killing a woman in Arizona in 1974 with such precision that FBI analysts were able to corroborate the crime by the time they landed in Texas.

The next morning, Holland brought eggs and coffee to Little’s cell in the Wise County Sheriff’s Office. For months, he would arrive each morning — but never too early, Little liked to sleep in — with breakfast, often McDonald’s and grits. They would chat about sports or politics, then Holland would wheel him down the hall to the interview room. The attention sent a subconscious message to Little that Holland cared about him.

The first order of business, under the extradition agreement, was to get confessions to the L.A. cases. Whereas Holland hoped — and would succeed — in bringing in police to question Little about homicides in their jurisdictions, Little refused to speak to L.A. detectives.

But as Holland and Little were about to discuss the L.A. homicides, Little took a detour — recalling how much he had enjoyed Las Vegas.

Had he killed anyone there? Holland asked.

Yes, Little replied, nonchalantly.

Holland had a choice — focus on L.A. or go with the flow. He decided to let Little drive the bus.

The conversation segued from Las Vegas to Mississippi, where he said he killed a transgender woman. Then Little talked about a woman he remembered as being particularly beautiful. As Holland took notes, Little motioned with his hand that he didn’t need to write any of that down — he hadn’t killed her.

Over the next few months in Texas and later in California, the detective tried to pry loose Little’s decades-old memories. It wasn’t easy. Little struggled to recall full names and wasn’t always sure in what town or county he had tossed a body. He was terrible at dates, often placing murders in the wrong decade. Holland came to call this the “time vortex.”

The ranger found cues to get Little on track. The best one was cars. Little was a car nut and could recall the make, model, engine size and horsepower of all his vehicles, and when he had purchased them.

In this instance, Little knew he had killed a woman in Las Vegas in 1993 because he was driving a yellow 1978 Cadillac Eldorado that he had purchased that year. He was driving that same car when he earlier strangled a woman in Perry, Fla.; as he squeezed her neck, “she started pointing up to the sky,” he said, reenacting the woman’s final motion.

Holland could tell when those golden confessions were coming — Little crooked his neck, squinted his eyes, and began stroking his cheeks, as he recalled a woman’s face, or a murder scene or dump site.

The ranger asked whether Little would draw portraits of his victims. Little agreed, and Holland set up a studio in his cell. The portraits — in watercolor, acrylics and chalk — could be surprisingly accurate. Earlier this year, the FBI posted a batch of portraits on its website and got a tip that helped crack a case in New Orleans.

After the confessions came the painstaking work — confirming killings. There won’t be time to prosecute Little for all the deaths, but authorities believe they can sufficiently tie him to a homicide to consider the case solved.

Holland brought in detectives from states nationwide to question the killer. They came from Arizona and Florida, Maryland and Kentucky, Ohio and Illinois, and more. Many left the interrogation room shocked at Little’s recall.

::

Holland has come to contradictory conclusions about Little. He seems to like the guy, saying he would happily get beers with him if he could. He professes admiration for his artistic talent, intelligence and memory.

At the same time, he ponders the victims’ final moments. He says Little is a sociopath with extreme psychopathic tendencies. He did evil things.

“The man is an absolute genius, and he has a sickness,” Holland said. “He doesn’t know why, and I don’t know why.”

For his part, Little said in a letter to The Times that he confessed because he wasn’t going to get another trial (Holland had been right — timing had played a role in Little deciding to talk). Little added he wanted to help victims’ families and, perhaps, exonerate someone convicted of one of his crimes. He said he had “found a friend in a Texas Ranger.”

Last December, Little pleaded guilty to the Odessa murder and was returned to California. Last month he pleaded guilty to four others in Ohio. Other jurisdictions have charged him in their killings. Meanwhile, Holland continues to press Little for clues while he still can. On each visit, Holland said, Little’s memory seems a bit hazier and the pressure mounts to find clues, to match names to the faces on the wall.

Last month, Holland videotaped Little talking about unmatched confessions so the FBI could post it to its website to generate tips.

Though Little has begun to show some remorse, the serial killer seemed gleeful in recounting his slayings. He recalled how hard it had been to strangle a woman in Arkansas. She was slippery from sweat and squirmed and screamed as he tightened his grip on her neck.

“She is fighting for her life,” he said, chuckling. “And I’m fighting for my pleasure.”

As always, Holland passed no judgment and quickly asked the only question that matters to him: “What did you do with her?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.