In Death Valley, a Jeep, back roads and a whole new perspective

Weird science, quirky history and plain fun lurk in the 3.4 million acres that make up Death Valley National Park.

Reporting from DEATH VALLEY NATIONAL PARK — It took me several trips here to realize this, but if you know where to look and time it right, Death Valley is one giggle after another.

Sure, it’s vast, wind-raked, sun-baked and empty-seeming. Yes, it will confirm your puniness in the universe. And it might kill you if you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time without water or cover.

But there’s plenty of weird science, quirky history and plain fun in these 3.4 million acres of dry lake beds, towering dunes and wind-scoured mountains, which have been a national park since only 1994. The last time I made the 215-mile drive from Los Angeles to Death Valley, in December with Times photographer Mark Boster, seemed especially revealing.

Part of this was the weather. The first storm in a year had just dumped a burst of rain, leaving puddles and green stubble in a place that’s famous for lacking them.

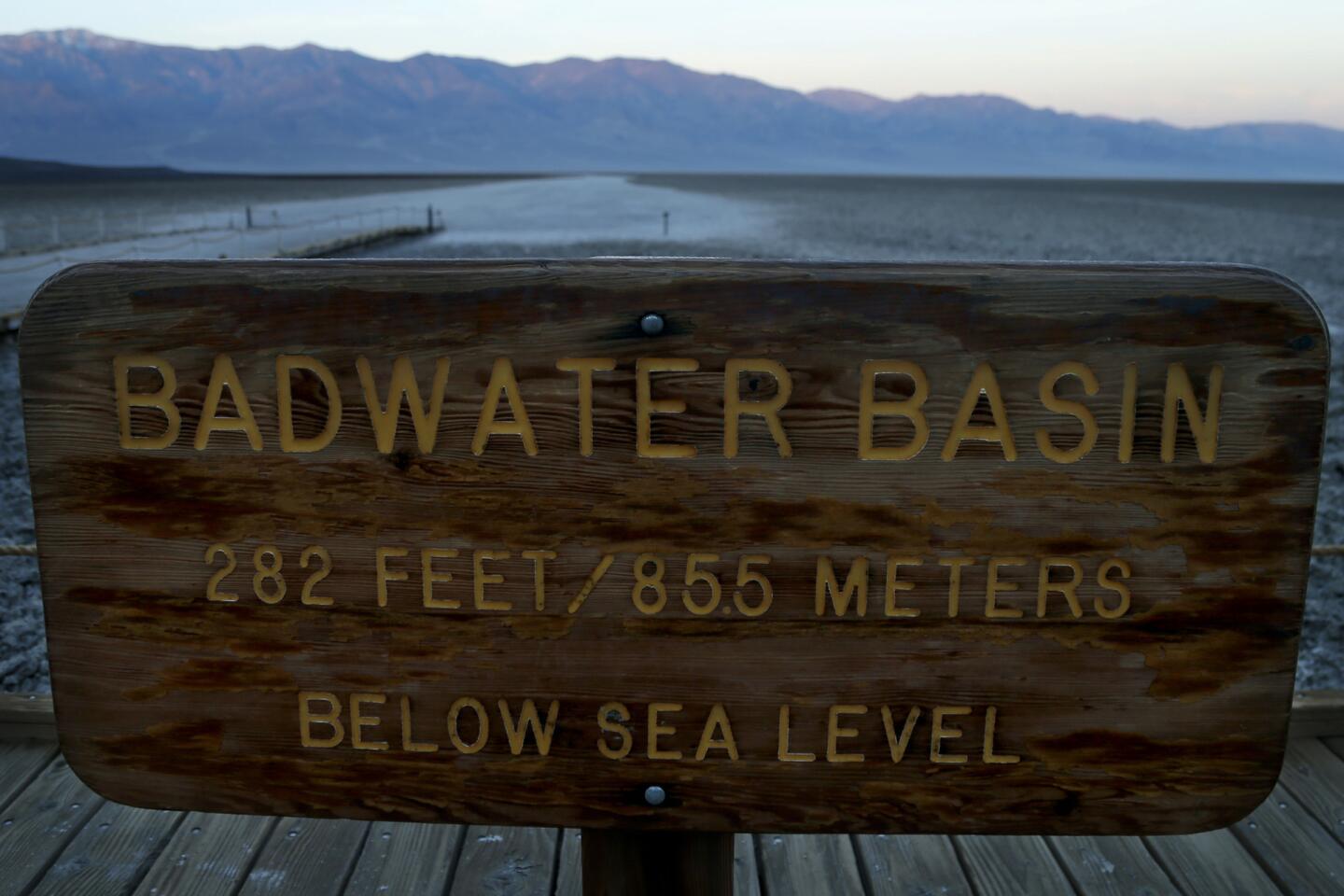

The other factor was where we went. This time, between visits to well-known spots such as the salt flats at Badwater (the lowest spot in North America, at 282 feet below sea level) and Dante’s View (where the wind threatened to blow us into Nevada), we spent hours in a Jeep on back roads in Titus Canyon and Racetrack Valley.

Those narrow, rocky, twisting routes weren’t especially comfortable, but they allowed us to see the landscape in a new way.

On Day 1, following California State Route 190 from the Owens Valley and down into Death Valley, we fell into a race with the setting sun and reached Badwater in the nick of time.

Pools of water gleamed on the crusty salt flats. Snow shone on Telescope Peak, about 10 miles west. Half a dozen French tourists took turns hollering “écho!” at the mountains rising abruptly in front of us — audio selfies. Affixed to the rock more than 280 feet above us, a small white sign marked sea level.

As the purple sky darkened, the distant ridgelines seemed to sharpen. The French fled for dinner. Suddenly it was very quiet, and I felt as alone as one of those golf balls the Apollo astronauts left on the moon in 1971.

If you’re carrying a camera, sunrises and sunsets matter here. Photographers scheme endlessly to capitalize on every one of them (especially in winter, when the sun comes up at a more civilized hour). But distances change those ambitions. Badwater is 41 driving miles from the Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes. Which are 65 miles from Dante’s View. Which is 96 miles from Scotty’s Castle. Which is 29 miles (mostly gravel) from the Racetrack.

If you’re not careful — or even if you are — you may end up the way we did on Day 2, rushing from Scotty’s Castle to the dunes at Mesquite Flat but arriving too late to catch the last of the golden light.

All that was forgotten on Day 3, when we turned off the pavement at Ubehebe Crater and rumbled onto 27-mile Racetrack Road. People mostly talk about the road’s eerie destination (see below). But if you’re a driver who likes kicking up a little dirt and a few loose rocks (in the right kind of vehicle), the road alone is notable.

Right away, a wild valley opens up. A washboard path winds through a Joshua tree forest as sprawling and Seussian as any in Joshua Tree National Park. At mile 20, you reach Teakettle Junction, a strange metallic oasis of dangling cookware where dozens of campers have autographed their kettles and hung them on the sign. At mile 27, you park and walk.

If you had asked me that night, I would have said Racetrack Road was the most fun I’d ever had driving in the park, even though we never got over 25 mph.

Ah, but then came Day 4. Titus Canyon Road, another unpaved 27-mile wonder, is a one-way route that begins just west of the park boundary and the Nevada state line. Once you’ve reached the gravel turnoff on Nevada State Route 374, you head straight across a flat patch of desert for several miles, then disappear into a canyon as the Grapevine Mountains rise around you, steadily taller, steeper and redder.

Usually, this is the busiest backcountry road in the park, but traffic was light on this early December weekday, and in three leisurely hours we saw just a handful of other vehicles. As I slowed from 20 mph to 10 and then to 5, the road fell and rose and the turns tightened into a series of hairpins above steep drops. There were limestone formations and petroglyphs.

At a turnout on a rare straight stretch, we stopped to inspect Leadfield, a ghost town that never really lived. Finally we squeezed through Titus Canyon Narrows, a 1 1/2-mile stretch where the canyon walls come within 20 feet of each other, and emerged just in time to catch a pink sunset.

And if you had asked me that night, I would have said that sunset was the happiest surprise of the trip. But then came Day 5.

It was our last morning in the park. We had decided to shoot dawn on the dunes at Mesquite Flat. Sure enough, by 6:30 a.m. the horizon had begun to burn red in the east, despite clouds overhead. We stood under a pair of skeletal trees.

Then came the raindrops, a strengthening drizzle dappling dunes that get perhaps 2 inches of rain per year. The sun was brighter now, but I had to look away because in the west, beyond the limbs of those skeletal trees, a rainbow arched above the darkened dunes.

Boster went nuts with his cameras, of course. I snapped too, but gave up after a while. In Death Valley that morning, there was more going on than any camera could capture. So I did the next best thing. I stood there, grinning like an idiot.

____

Death Valley National Park timeline

Circa 1000: Ancestors of the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe arrive in the area now known as Death Valley, relying on desert plants and animals for sustenance.

1849: Gold Rush seekers from Utah roll wagons into the hot, dry valley and barely escape with their lives. “Goodbye, Death Valley,” said one of the survivors. Name sticks.

1870s: Mining begins with a brief silver rush in Panamint City, now near the park’s southwest corner.

1880s: Vast deposits of borax (a naturally occurring compound used in household cleaning products) inspire a new kind of mining in the valley. Soon Chinese crews are collecting borax salts at Furnace Creek, using mule teams to haul wagons to railheads.

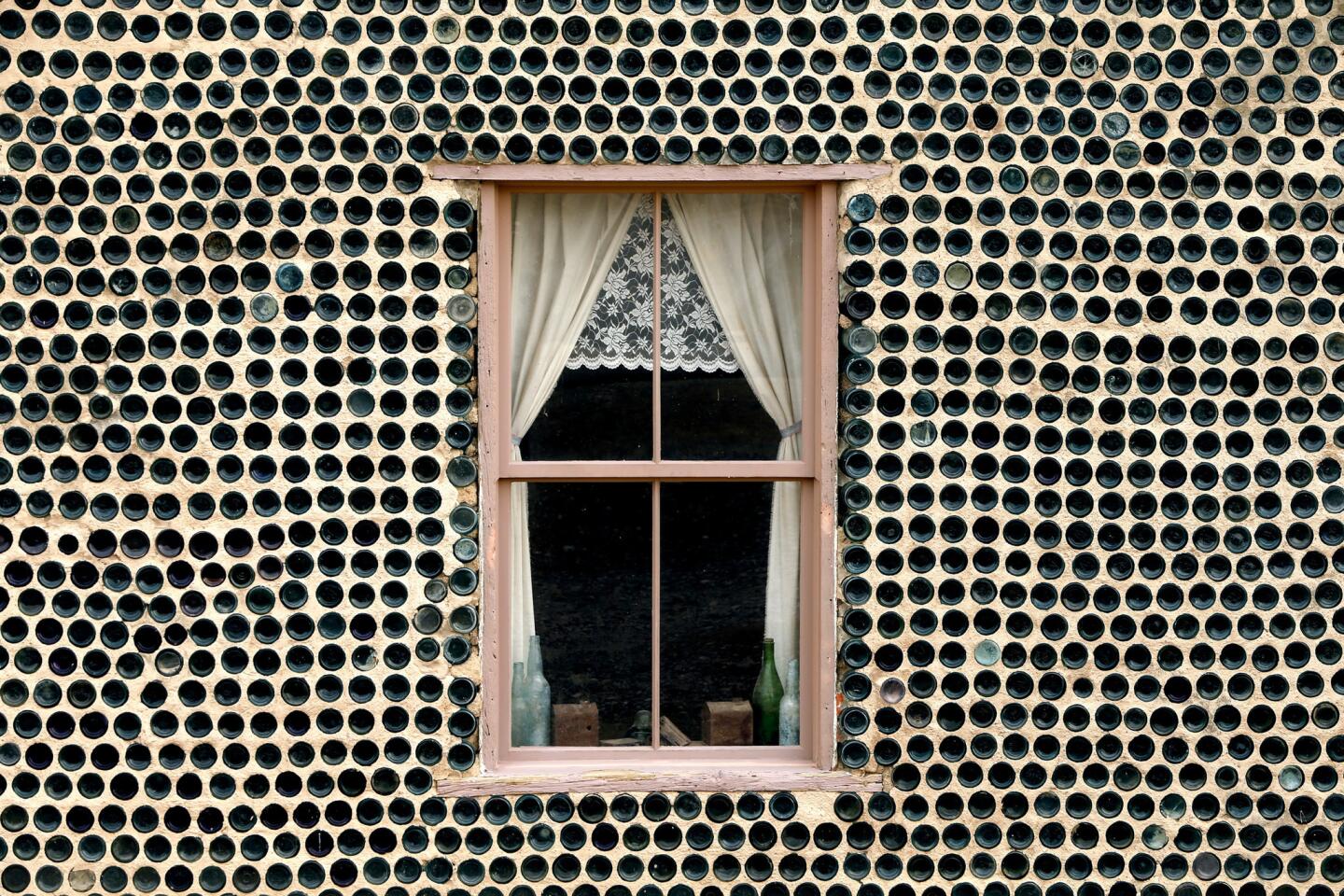

1904: Another rush of miners arrives when gold is found east of Death Valley; the town of Rhyolite, Nev., sprouts but later withers.

1913: On July 10, the highest temperature on record is recorded at Furnace Creek: 134 degrees.

1922: Chicago insurance industry titan Albert Johnson and his wife, Bessie, having become friends with an amiable con man named Walter Scott, put up the money to build a Spanish-style vacation house in Grapevine Canyon. Construction goes on for nine years at the home, later known as Scotty’s Castle.

1926: The Pacific Coast Borax Co. (later known as U.S. Borax) starts building a luxury inn at Furnace Creek. Like Scotty’s Castle, the project relies heavily on Shoshone workers. The Furnace Creek Inn opens with 12 rooms the next year; the Furnace Creek Golf Course comes a few years later.

1930: The “Death Valley Days” radio show premieres, sponsored by 20 Mule Team Borax. It appears on television from 1952 to 1970, with future president Ronald Reagan as host.

1933: President Hoover designates the area as Death Valley National Monument. Workers from the Civilian Conservation Corps set about improving roads and buildings.

1940s: The Johnsons die, leaving Scotty’s Castle to a California charity that supports Walter Scott and operates the castle as a hotel for many years.

1954: Walter Scott, a.k.a. “Death Valley Scotty,” dies at 82.

1966: The Fred Harvey Co. buys the Furnace Creek Inn and other lodgings from U.S. Borax; they are now operated by Xanterra Parks & Resorts.

1967: Dancer and artist Marta Becket, 43, agrees to rent a historic building at Death Valley Junction, just east of the national monument, and dubs it the Amargosa Opera House & Hotel. The next year, Becket begins performing on Friday, Saturday and Monday nights and continues for more than four decades.

1970: The National Park Service buys Scotty’s Castle from the Gospel Foundation of California.

1976: Congress closes the monument to new mining claims.

1994: President Clinton signs legislation establishing Death Valley as a national park, now 3.4 million acres.

2000: The Timbisha Shoshone Homeland Act allots the tribe acreage within the park, including a 40-acre residential area at Furnace Creek, where 50 to 60 people live.

2013: Becket makes a farewell “sit-down” Amargosa performance at age 88.

December 2014: Dancer and Becket protégé Jenna McClintock begins offering Friday, Saturday and Sunday shows at the Amargosa Opera House, including dances choreographed by Becket. Performances are expected to continue through April or May, followed by a summer hiatus. (Info: [760] 852-4441.)

SOURCES:

National Park Service, www.nps.gov/deva. Furnace Creek Resort, www.furnacecreekresort.com. Amargosa Opera House & Hotel, www.facebook.com/amargosaoperahouseandhotel.

____

In Death Valley’s Racetrack, moving rocks and eerie backcountry

Maybe you’re hard to impress. Maybe, having seen the near infinities of Death Valley’s Badwater Basin and crept up the highest dune at Mesquite Flat, you’re thinking: Weird. But not weird enough.

If so, the Racetrack is for you. This backcountry outpost is where breadbox-sized rocks mysteriously make tracks across a pale, flat, dry lake bed, evoking thoughts of moon landings and Bonneville time trials. Photographers and conspiracy theorists love the place, especially when the sun is low.

To get there, you need a vehicle with high clearance and heavy-duty tires (we had a Jeep) and tolerance for a bumpy ride. Unless you’ve competed in the Baja 1000, give the drive 90 minutes to two hours each way from Ubehebe Crater.

From the pavement’s end (near the crater), it’s a 27-mile rumble. At mile 26, you encounter the Grandstand, an enormous hunk of dark quartz monzonite at the north end of the lake bed. About mile 27, you park and look for rocks and tracks.

Scientists theorize that the lake evaporated about 10,000 years ago, leaving dried mud 1,000 feet or more deep. There are dozens of rocks and strange tracks — some straight, some curved, some that suddenly veer — but they’re not a mystery anymore. Last year researchers Richard and James Norris found that if ice sheets form on the lake bed, then break up as temperatures warm and wind kicks up, the windblown, fragmented ice sheets glide across the lake bed and nudge the rocks hard enough to move them, millimeter by millimeter.

The Norrises documented 60 moving rocks in the winter of 2013-14, including one rock that traveled 245 yards in two months.

But wandering the flats is still spooky and sometimes breathtaking, especially if there are clouds floating about when the sun is low. The lake bed is about 3 miles long and 2 miles wide, so leave yourself time to meander. But don’t move any rocks. And if there’s wet mud, don’t leave tracks.

____

Death Valley’s Racetrack can’t stop the Steffenses’ adventure

By the time I met Wolfgang Steffens, he had already spent about two years on the road. Since leaving his home in Finland, he had covered big chunks of Europe and Africa on a BMW motorcycle with a sidecar. Road name: Silver Wolf.

In other words, Steffens, 49, had seen a lot and survived plenty of scrapes. Now he was in the outback area of Death Valley known as the Racetrack, tiptoeing from rock to rock with a camera.

“I’ve always wanted to go to Death Valley,” he said. “And I read that there was a cool rock thing here.”

Before hitting the road, Steffens worked as an electrical engineer. Since August 2012, he and his wife, Ilta, and their dogs have been slowly circling the world on a pair of motorcycles (and sidecar), having adventures, promoting veganism and blogging (www.sauerkraut-tofuwurst.com).

In short, they are vegan biker bloggers. Their plan is to spend five years on the road, Steffens said, “unless we run out of money.”

With the three dogs bouncing along in the sidecar, they had covered 30 countries in Europe and Africa, then shipped the bikes to North America. Here, they’d been happily surprised by American hospitality — “people invite you to their house!” — and saddened by the loss of their eldest dog. Hertta, a 14-year-old poodle mix, died in the Pacific Northwest.

Now they were headed to Latin America. Because his wife didn’t like the look of Death Valley’s back roads, Steffens had a day to explore on his own. The sun was sinking, and it was time to drive out. We said our goodbyes.

But an hour later, photographer Mark Boster and I found Steffens by the side of the road, mournfully perched on his idle bike. The rocky route had cracked its front fork and partly collapsed its frame. He couldn’t steer, 13 miles from the nearest blacktop.

“Luckily,” Steffens told us, “there was no ditch.” Otherwise, he was very quiet. “Devastated,” he said later.

We unloaded his bike, nudged it closer to the edge of the road, put his gear in our Jeep and took him to his wife and dogs at the Furnace Creek campsite. By the time Steffens thanked us once more and waved goodbye, it was fully dark. The more Boster and I imagined the time and money it would take to get them rolling again, the sadder we got.

But apparently you can’t keep a vegan biker down, especially one with mechanical aptitude and friends in Las Vegas.

By the next afternoon, a Vegas friend with a truck was towing the Silver Wolf to civilization. Within about a week, Steffens told me later by email, the bike and sidecar were rolling again. They spent New Year’s Eve at Lake Havasu.

It would take several more weeks to fix deeper issues with the bent sub-frame and leaking rear shock absorber. By the end of January, Steffens wrote me, he expected to be in Phoenix, where they could “prepare the bikes and ourselves to steer toward Central and South America.”

____

Death Valley National Park: Do’s and don’ts

Don’t be a summer person. Not only do temperatures routinely approach 120 degrees (with overnight lows in the 90s), but, believe it or not, it’s when the park is often most crowded. Death Valley’s busiest month in 2014 was August, when 123,363 visitors showed up, many of them Europeans with little desert experience. (The Inn at Furnace Creek Resort, the park’s fanciest lodging with rates starting at $295 a night, usually closes for most of the summer.)

Don’t take your Mini Cooper onto any of the park’s rugged back roads. Instead, investigate Death Valley Farabee Jeep Rentals (101 California 190, Furnace Creek; [760] 786-9872, farabeesjeeprentals.com). The Jeeps Richard Farabee rents aren’t cheap — $195 to $235 per day is typical — but their four-wheel drive, high clearance and emergency communication devices give comfort to newcomers.

Do consider sleeping at the Ranch at Furnace Creek (California 190, Death Valley; [800] 236-7916; www.furnacecreekresort.com), which is the biggest (224 rooms), family-friendliest lodging in the park. Rates generally are $139 to $310 for rooms and cabins. There’s an on-site campground too, along with a well-stocked general store.

Do consider eating at the Ranch at Furnace Creek. Even if you sleep elsewhere, odds are good you’ll end up hungry near Furnace Creek. Do consider the 49’er Cafe (the Ranch at Furnace Creek, California 190, Death Valley; [760] 786-2345, www.furnacecreekresort.com), which offers comfort-food breakfast, lunch and dinner. (Dinner main dishes $11.75 to $23.95.) Prices may seem a bit high, but remember the remote location. A few steps away, the Wrangler offers steaks and seafood dinners at even higher prices (main dishes $21.95 to $37.95).

Distance from the Ranch at Furnace Creek:

1.2 miles southeast: Do have breakfast at the genteel Inn at Furnace Creek Dining Room (328 Greenland Blvd., Death Valley; [760] 786-3385, www.furnacecreekresort.com), where meals cost only a few pennies more. Eating here is an excuse to wander the four-star, 66-room property, which dates to the 1920s. Don’t miss the lavish pool.

3.4 miles southeast: Don’t head for Zabriskie Point unless you’re sure it’s open. Zabriskie, perhaps the valley’s most famous viewpoint, has been closed since late 2014 for repairs. It’s tentatively due to open after April 30. Until then, you might hike the nearby Golden Canyon Interpretive Trail (1 mile, one way).

17 miles south: Do see Badwater. It’s the lowest point in the valley, 282 feet below sea level. The site is basically a parking lot, restroom, plaque and foot trail leading into a vast, dry lake bed. Stop at sunset or sunrise or both.

41 miles south: Do brace yourself for a breeze at Dante’s View. From this perch, more than 5,000 feet above sea level, you can see almost straight down at Badwater, which looks like spilled milk for miles, or gaze across the valley to Telescope Peak, often capped by snow. You can also see much of the valley floor as it runs north.

24 miles northwest: If the sun is about to set or dawn is imminent, do check the views at Mesquite Flat Sand Dunes. These dunes, about 2 miles east of the Stovepipe Wells Village Hotel, aren’t the tallest dunes in the park, but they’re the easiest to reach from Badwater or Stovepipe Wells. The highest dunes are about 2 miles’ hike directly north of the parking lot. If you’re a photographer looking for virginal dunes, the foot traffic is usually lighter to the east. Whether you’re a photographer or not, sunrise and sunset are great times to hang around. The colors can be riotous.

26 miles northwest: If your gas tank is low, do consider Stovepipe Wells Village (51880 California 190, Death Valley; [760] 786-2387, www.deathvalleyhotels.com). It’s the main alternative to the Ranch at Furnace Creek. The Stovepipe Wells Village Hotel (rooms for two, $117 to $175.50) is by the Tollroad Restaurant, Badwater Saloon, pool, gift shop, general store and a gas station that’s often 30 cents a gallon cheaper than the Chevron station at Furnace Creek. Among the drawbacks: limited Wi-Fi, no phones in the hotel rooms and poor cellphone reception.

57 miles northwest: If you’re doing Scotty’s Castle, do Ubehebe Crater too (lat.ms/1yn5U22). It’s about 600 feet deep and was caused by an explosion of volcanic steam. It’s surrounded by cinder fields and raked by wind, its red-and-black rim elaborately lined by erosion. You can circle the rim (about 1½ miles) or hike to the bottom. But the trip back up, the park service says, “can be exhausting.”

39 miles north: Don’t expect to spend a long time in Rhyolite, Nev. It’s a Bureau of Land Management-tended ghost town just east of the park. Though it thrived from 1904 to 1916, most of the buildings are behind barbed wire, and one that’s unfenced is covered with graffiti.

55 miles north: Do take a tour of Scotty’s Castle (123 Scotty’s Castle Road, Death Valley; [760] 786-2392, lat.ms/1Cy684n). One 50-minute ranger tour (offered year-round at $15 per adult) covers the inside of the castle, which is full of furnishings from the 1920s and ‘30s, when Death Valley Scotty shared desert adventures with his wealthy Chicago sponsors, Albert and Bessie Johnson. The Underground Tour (not offered in summer) focuses on what’s beneath the castle, including the compound’s hydroelectric system.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.