Bill James on MLB: Too much is foul, and more thoughts on making the game better

BOSTON — It would be too much to say Bill James and Rob Manfred are kindred spirits. But, when the father of modern analytics talks, we listen.

“Baseball has terrible aesthetic problems,” James said. “We all know that. But, in many cases, it isn’t the rules that are causing them. It’s the lack of new rules.”

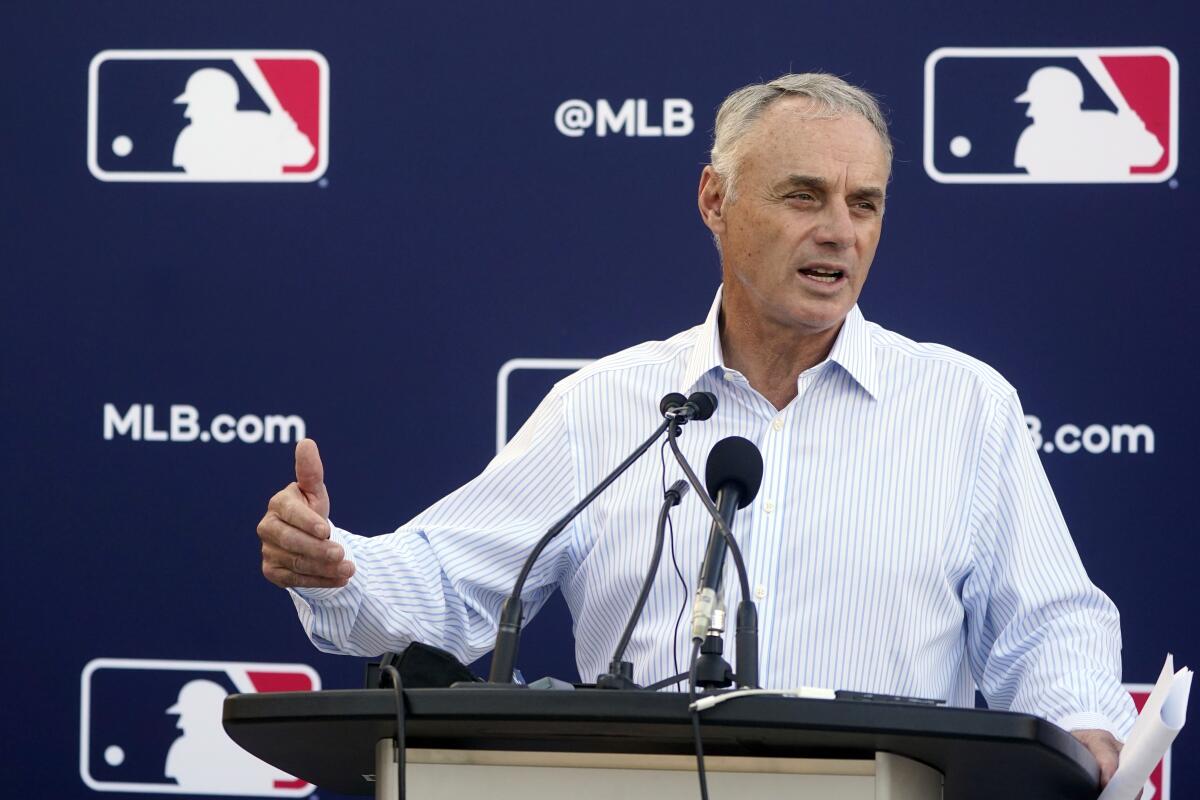

These days, Manfred is the face of the owners’ lockout, the chosen representative of the billionaires who stand between America and spring training. In happier times, and for years now, Manfred has tried to nudge a tradition-bound sport toward changes that he believes could make baseball more exciting to watch.

Stephen Curry is one of the most popular players in NBA history, but he might not be without a radical rules change. Curry is the all-time leader in three-pointers.

Thanks to stubborn owners, the MLB lockout will see fans lose seats, ushers and concessionaires lose livelihoods, and TV viewers lose a companion.

The addition of a completely different way to score did not destroy the fabric of the NBA. More than 40 years later, baseball is still arguing about how many seconds a pitcher can take between pitches.

The players’ union indicated Sunday it is willing to accept a pitch clock in 2023, as well as restrictions on defensive shifts, provided players and owners reach agreement on a collective bargaining agreement for the 2022 season. In terms of aesthetics, James suggests a far more radical change.

Today, a batter can foul off an infinite number of pitches with two strikes, with no penalty. Pitchers throw harder than ever, batters swing harder than ever, and foul territory in modern ballparks is smaller than ever.

In each of the last five seasons — and never before, based on available data from the Baseball Reference and Five Thirty Eight websites — it is more likely that a strike will be fouled off than put into play.

“The hitters have learned to exploit that rule to extend at-bats, which is one of the things making the game longer,” James said, “and you need to make adjustments.”

James proposes that a batter can foul off one pitch with two strikes. Foul off another pitch, and you’re out.

Heresy? Maybe. But, as James noted, baseball had been played for decades under the premise that a runner should knock over the catcher if he is guarding home plate, and that a team should change pitchers whenever it wanted. No more, since the rules changed.

“Everybody accepts that now,” James said. “Nobody fights it.”

The designated hitter is a radical rules change. James is not fighting it, even if National League owners are ready to surrender their half-century of resistance, but he wonders if the DH has outlived its purpose.

In 1972, the last season before the introduction of the DH, teams averaged 3.7 runs per game. In 2021, NL teams averaged 4.5 runs per game and American League teams averaged 4.6.

“I’m old enough to remember that they adopted the DH because the run-scoring levels were abysmally low,” he said. “That is no longer true.

“I would rather get rid of the DH, but I understand that is not the popular side.”

Lockout notwithstanding, James said baseball is a good business, for those that can afford to buy a team.

“I think franchise values are going up because, unfortunately, we live in an America in which more and more of the wealth in society is concentrated in fewer hands,” he said. “And, when you have more people who have obscene wealth, the price of things you can only buy with obscene wealth goes up.”

The man whose name is synonymous with baseball analytics said the data in another sport piques his interest these days.

“Basketball analytics are just fascinating to me,” James said. “To me, the discussion is more alive at this moment, and moving in relevant ways, than in baseball.”

The new frontiers in baseball analytics involve biometrics, biomechanics and neurological assessments — that is, ways to improve performance through science rather than through statistical evaluation alone.

However, even if the fundamental concepts of baseball analytics are established among teams, James says the implementation varies widely.

“The extent to which analytics have been exploited successfully by teams is, like, 1%,” he said.

“What bothered me in the 1970s is that teams acted on lots of irrational assumptions. I don’t want to get into the details of it, but there are still lots of irrational assumptions embedded in the way baseball does things. There’s still a lot of things that we’re not doing in a smart way.”

The “Moneyball” season is 20 years old. The conventional wisdom — that is, the assumption — is that every team is invested in analytics now, to the point where no team has a huge advantage any more.

James scoffed.

“The [Tampa Bay] Rays are getting a huge advantage, because they do it better than anybody else does,” he said. “The Dodgers.

“There are still smart teams and stupid teams.”

Major League Baseball’s lockout is now in its third month. What happens now that Commissioner Rob Manfred has canceled the first week of the season?

James spoke with The Los Angeles Times after a panel discussion at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, where the baseball analytics panel included James, the director of baseball operations for the Rays, and the former director of research and development for the Dodgers, who now runs his own analytics company.

The traditional major league season lasts 162 games. With the lockout in force, the moderator asked whether the panelists would take the over or under on a 144-game season in 2022.

James took the under.

“It’s the same principle as an airline,” he said. “If the airline tells you your flight is going to be 20 minutes late, you’ve got a 50-50 chance of being four hours late. When they start canceling games, it just gets easier.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.