Rob Manfred has a vision to improve baseball and it’s more radical than you think

Reporting from NEW YORK — Pace of play this, and pace of play that. Rob Manfred did not want to talk about it. Not at first, anyway.

The commissioner of baseball wanted to play football trivia. Let’s do this.

“Bob Griese,” Manfred said. “Great quarterback. Won two Super Bowls. You know how many passes he threw in those two Super Bowls?”

I guessed 30. Manfred said 21.

The correct answer was 18. That was 45 years ago.

“Can’t happen in today’s game, because they altered the rules,” Manfred said, “When football decided that it needed more action late in the game, there was a seismic shift in the value of quarterbacks and wide receivers as opposed to running backs.”

In his last two Super Bowls, Tom Brady threw 113 passes. He was the game’s most valuable player both times. The last running back to win Super Bowl MVP did so 19 years ago.

For that matter, the last true center to win NBA MVP – the Lakers’ Shaquille O’Neal – did so 17 years ago. The NBA today does not even list “center” as a position on its All-Star ballot.

“The game they play today, with the three-point shot, that’s affected positions,” Manfred said. “More than half these teams play without a real center. They changed the game.

“I think, for the NBA, that’s been a good thing. I think, for the NFL, that’s been a good thing. I think, for us, we are at a point where analytics in particular have accelerated the pace of organic change in a way that we need to stop and think, ‘Hey, do we need to make an adjustment?’ ”

If you’re focused on the elimination of actual pitches in an intentional walk, or on the likelihood of a 20-second pitch clock, you’re missing the point.

“That’s my fault,” Manfred said. “Pace has gotten too much attention.”

That leads to the assumption among some fans that Manfred believes baseball would magically become far more popular if only he could knock five minutes off the time of a game.

“God, no,” Manfred said. “It’s one part of a really complicated, multi-faceted approach to ensuring the product we’re putting out there is the most compelling product possible.”

During the World Baseball Classic, Manfred visited Japan and South Korea, where he said games take longer but fans sing, chant and play instruments. The commissioners of the leagues there told Manfred no one complains about time of game.

Maybe the major leagues can borrow from the more joyous fan experiences in Asia and Latin America, even at the risk of adding five minutes to the game. Maybe television broadcasts can shorten commercial breaks by adding ads to a corner of the screen during play. And, yes, maybe the players and coaches could cut back on the in-game caucuses.

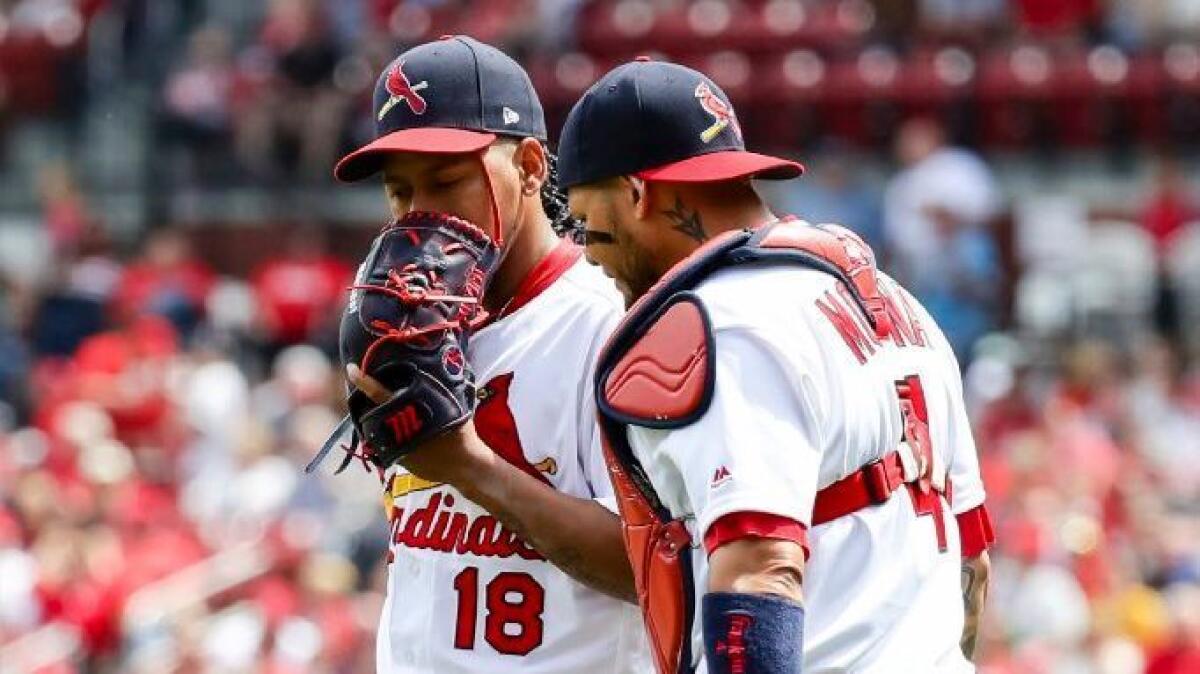

“The stuff where nothing is going on – Yadi Molina is making his 93rd trip to the mound, or whoever the catcher is, I don’t mean to pick out a guy – dead time is an issue,” Manfred said.

That might be the relatively easy part of the change Manfred seeks. The much more challenging part involves accelerating action within the game itself, and the trial balloons have included restrictions on defensive shifts, altering the strike zone and limiting the use of relief pitchers.

Should Manfred really be legislating strategy? Teams now pay millions of dollars to baseball operations executives to devise clever and efficient ways to win. If a team believes its best chance to win includes a lineup of walk-prone, strikeout-prone sluggers that rarely put the ball in play, and an eight-man bullpen that makes four or five pitching changes per game a common occurrence, should that not be the team’s decision?

“Let’s say I decide the root of all evil is overuse of relief pitching,” Manfred said. “A team that has built its pitching from the ninth inning back to the eighth, back to the seventh, back to the sixth is going to be more reluctant to look at that rule change than the guy who’s got four or five great starters and not quite the same back end of the bullpen.

“But does that mean that those sorts of changes shouldn’t and can’t be enacted in the game? No.”

In February, Manfred publicly blamed the players’ union for a “lack of cooperation” and threatened to exercise his right to unilaterally implement rule changes next year if the players did not agree before then.

The players share the goal of making the game more popular. They are not yet persuaded that Manfred necessarily has the right ideas about how to do that.

“It’s always a very delicate balance when you start to talk about rules that are going to change the game on some level, and whether they’re going to manifest themselves on the field in the fashion everyone hopes or thinks they are going to,” said Tony Clark, the union’s executive director, “while also making sure not to take those who currently love and enjoy the game and change it such that they no longer do, while also hoping to engage the next generation.

“Often, the guys who are affected most are the guys on the field.”

For instance, Clark said, in an era where players throw harder than ever, would it make sense that a pitcher throwing at 100 mph might need more recovery time between pitches than one throwing at 90 mph? He would prefer that owners and players obtain and explore such data before rushing to adopt a pitch clock.

“Asking guys who are throwing harder to speed up can be a delicate proposition,” Clark said.

Same for rules changes that, say, favor contact hitters over free swingers, or require relievers to pitch to more than one batter. Manfred is not the guy leading a union in which sluggers and left-handed relief specialists could be at risk of taking huge pay cuts or losing their jobs outright, although in fairness the market already started to devalue one-dimensional sluggers last winter.

The owners and players are expected to meet later this season, trading ideas for how to grow the game. The players might suggest that the game itself is less of a problem than selling the game, and that initiatives might run more along the lines of marketing and community outreach, less along the lines of significant rules changes.

“You’ve got to work a lot harder to get a consensus among owners, players and stakeholders to make that kind of change,” Manfred said. “Unlike dead time, where everybody can agree dead time is bad, somebody’s ox gets gored in that type of change.

“That means it’s harder to get there. That doesn’t mean it’s not worth talking about.”

Without an agreement, Manfred and the owners would have to decide whether incremental change is preferable to alienating the players and their formidable union. In a business that generates $10 billion per year, who blinks, and who risks goring a golden ox?

Follow Bill Shaikin on Twitter @BillShaikin

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.