Appreciation: Hank Aaron’s cherished connection to Bud Selig and Wisconsin will be missed

In recent weeks, baseball lost an important doubleheader. First, it was Tommy Lasorda, a Hall of Fame personality. Now, it is Henry Aaron, a Hall of Fame player. Thankfully, for all of us, both went deep into extra innings.

Do they allow cellphones in heaven? Maybe somebody could wander by and shoot the scene, as Lasorda greets Aaron and starts telling him how he could have gotten him out with a hard slider down and away. Aaron will chuckle, telling Lasorda he couldn’t have gotten him out with a deer rifle.

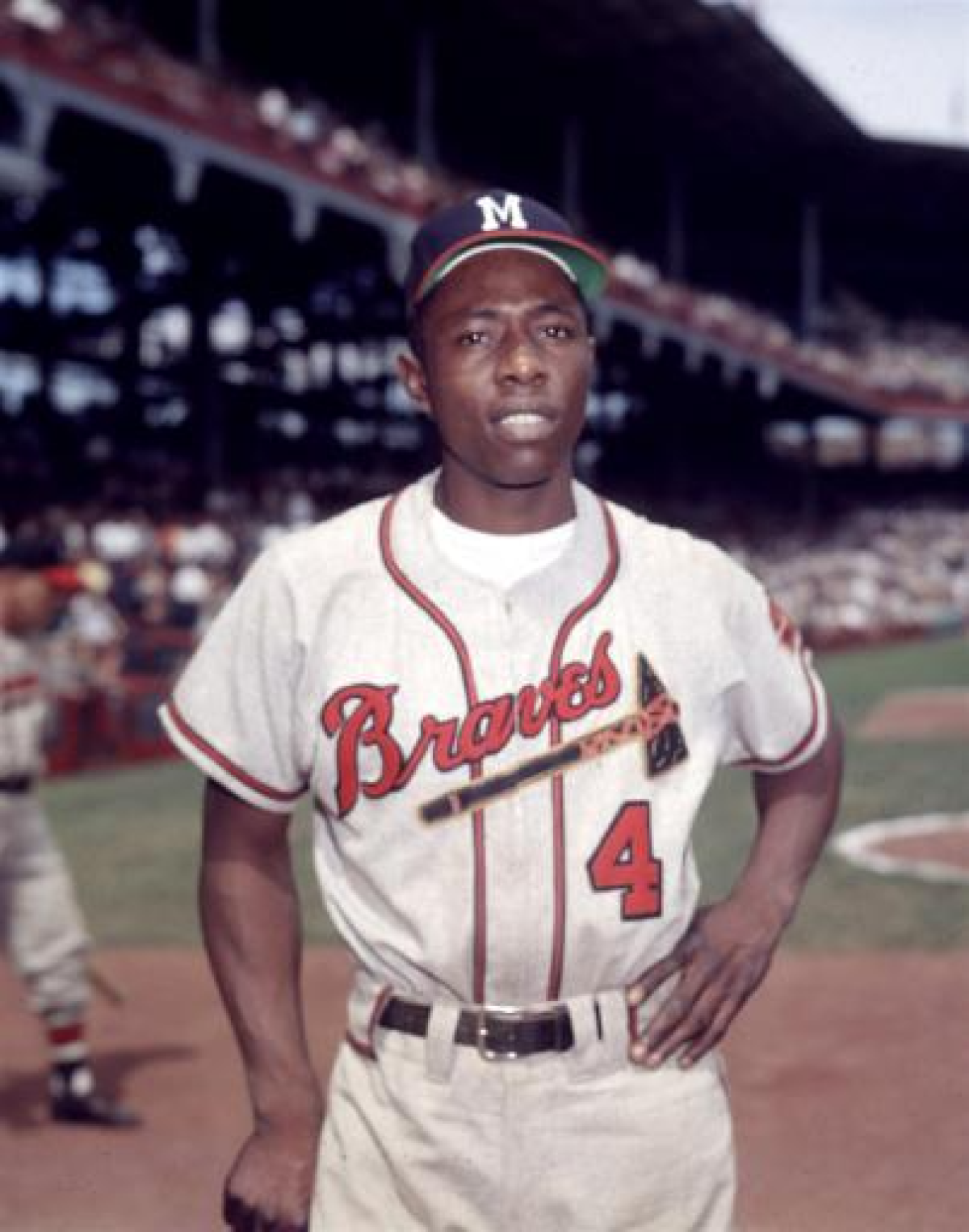

The obituaries about Aaron have, necessarily, delved into the racism surrounding his pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record. Aaron was a Black man chasing a white man on a pedestal. That 715th home run would make him, numerically, the greatest home run hitter in the history of the game.

Aaron broke Babe Ruth’s career home run record in 1974 despite enduring racism and went on to hit 755 homers in a 23-year career.

Aaron’s pursuit of that brought out the worst in us. He received thousands of letters filled with vitriol. He cautioned Atlanta Braves teammates to sit away from him on the bench. The sports editor at the time of the Atlanta Journal, Lewis Grizzard, planned extensive coverage of the day the homer was hit. He also had a staffer write an Aaron obit, just in case.

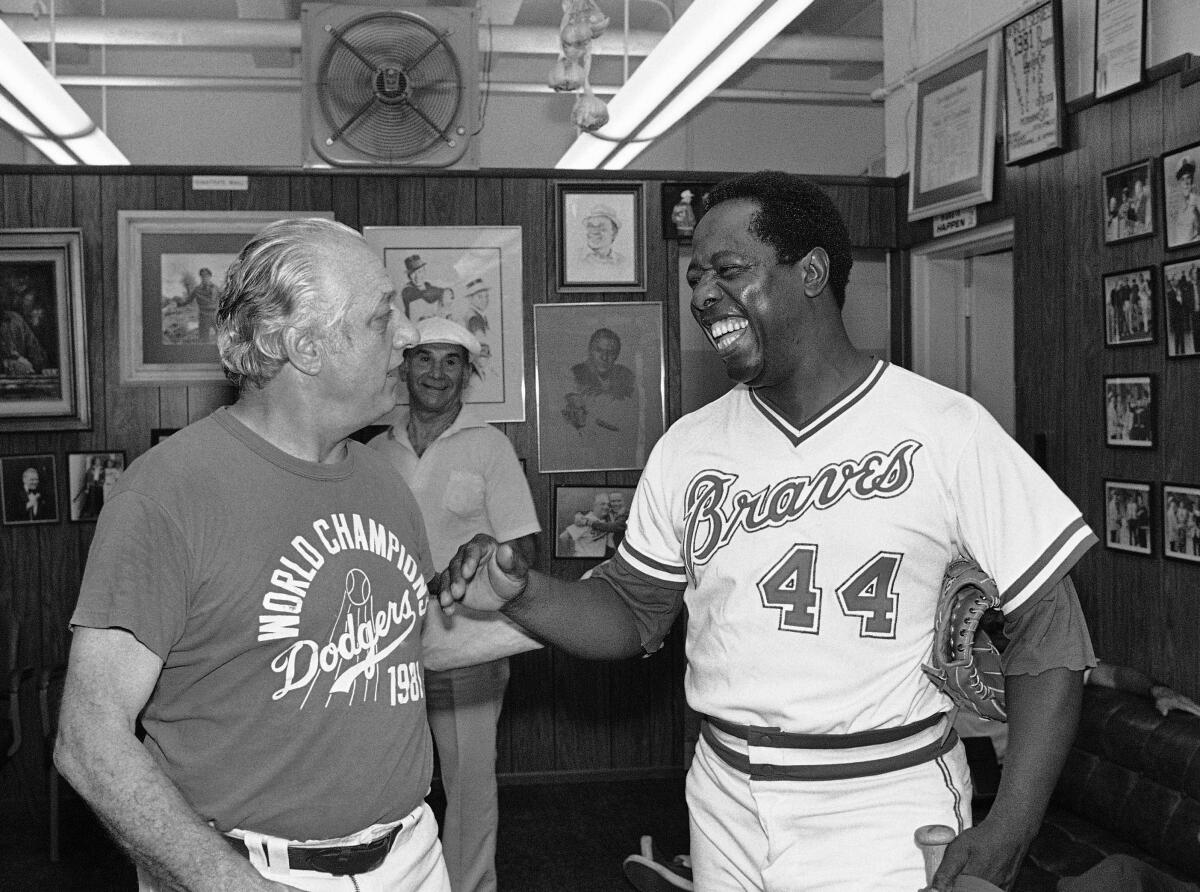

Aaron hit No. 715 on April 8, 1974. The Dodgers were the opposing team, Al Downing was on the mound, and Lasorda was in the dugout as a coach. Fittingly, Vin Scully, the poet laureate of baseball and, often, real life, was in the announcing booth. Without saying so directly, Scully sent the racists back into their holes.

“A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South,” Scully intoned, as only Scully could, “for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

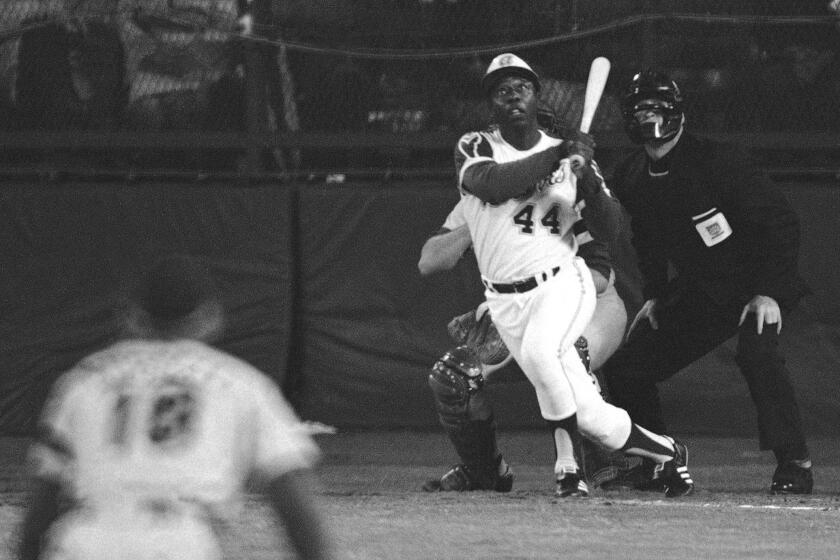

Hank Aaron hits his 715th career home run.

If there was mostly Joy in Mudville for that magic moment, there was the same in Wisconsin, where I grew up in a town to Milwaukee’s north, riding my bike to Little League games and pulling off to the side when it was time for Aaron to bat for the Braves. We fans had to focus, because Aaron did.

When Aaron was beginning his march to stardom with the Braves in the mid-1950s, our town had a star of its own, minor league catcher Johnny Roseboro, of the Sheboygan Indians. Roseboro would become a Dodgers star. Like Aaron, he was Black. In Sheboygan, I don’t remember that it mattered. They were ours, our stars, our heroes. If you had a uniform choice for your Little League team, you always opted for No. 44, Aaron’s number, if you could get it. If you couldn’t, Roseboro’s number, which I no longer remember, was the next choice. It was just baseball, not sociology.

Maybe I was too young. Thankfully, I was too young.

The racism that stunk up Aaron’s pursuit of the home run record was not lost on little Sheboygan. In anger, a fan named Bryan Walthers, then in his late 20s and having moved upstate from Sheboygan, wrote a letter to Aaron, encouraging him to not let the jerks get him down. Aaron replied on June 4, 1973, about a year before he broke the record, in something sounding much more heartfelt than a form letter:

Dear Mr. Walthers,

I want you to know how very much I appreciate the concern and best wishes of people like yourself. If you will excuse my sentimentality, your letter of support and encouragement meant much more to me than I can adequately express in words.

It is very heartwarming to know that you are in my corner. I will always be grateful for the interest you have shown in me. As the so-called “countdown” begins, please be assured I will live up to the expectations of my friends.

Wishing you only the best, I am, most sincerely,

Hank Aaron (and signed).

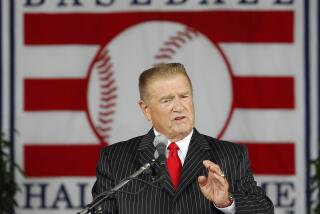

Walthers is white. So is Bud Selig, who was among Aaron’s best friends for more than 60 years, through his time well before he became owner of the Milwaukee Brewers and baseball’s commissioner. Aaron first made it to the big leagues in Milwaukee, getting a spot on the 1954 roster when the outfielder the Braves had acquired from the New York Giants and counted on for greatness — the man who hit “the shot heard ‘round the world,” Bobby Thomson — broke his leg in Braves spring training. Selig was a college accounting student then, but had access to the Braves because his father’s car dealership provided autos to the players. And so they met, two men from worlds apart.

Friday, Selig was crushed. “I just talked to him the other day,” he said. “We usually talked a couple of times a week. The last time, his wife, Billye, was on the phone and telling me to get on Hank about his weight. I did, but I knew he would ignore me.”

Selig talked about where he and Aaron might have been headed Sunday, had not each aged a bit and had there not been a pandemic. The Green Bay Packers play for the NFC title in Lambeau Field.

“We went to Packer games so many times together,” he said. “We’d drive up, have lunch at the same place, go to the game. I will miss that. I will miss him.”

Selig said that, on one of their recent walks on the streets of Washington, Aaron said something to him that brought him to tears.

“Still does today,” he said.

“He said to me, ‘Who would have ever thought all those years ago that a Black kid from Mobile, Ala., would break Babe Ruth’s home run record and a Jewish kid from Milwaukee would become commissioner of baseball?’ “

In the twilight of Aaron’s career, Selig brought him back to Milwaukee from Atlanta for a couple of seasons with the American League Brewers. For many of us who had grown up with the Braves, it never seemed right that Aaron was playing in the American League, but Selig did the right thing by bringing him home.

Barry Bonds, Magic Johnson, Stacey Abrams, Barack Obama, Vin Scully and Mike Trout are among those remembering baseball great Hank Aaron, who has died at 86.

Aaron hit his 755th, and last home run, on July 20, 1976. It came, fittingly, in Milwaukee County Stadium. Selig, like Aaron 86 years old, was asked if he remembered that final home run.

“Remembering stuff is kind of hard these days,” he said, then added quickly, “But I think it was against [the Angels’] Dick Drago.”

Indeed, it was.

There are statues of Aaron at the major league ballparks in Milwaukee and Atlanta. There is also one at Carson Park in Eau Claire, Wis., where he stopped along the way in the minor leagues. Never too big, too busy or too removed from his baseball roots, Aaron came to Eau Claire the day they dedicated it.

Now he is gone, as is Lasorda.

Tom Hanks was wrong. Just for a day or so, there is crying in baseball.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.