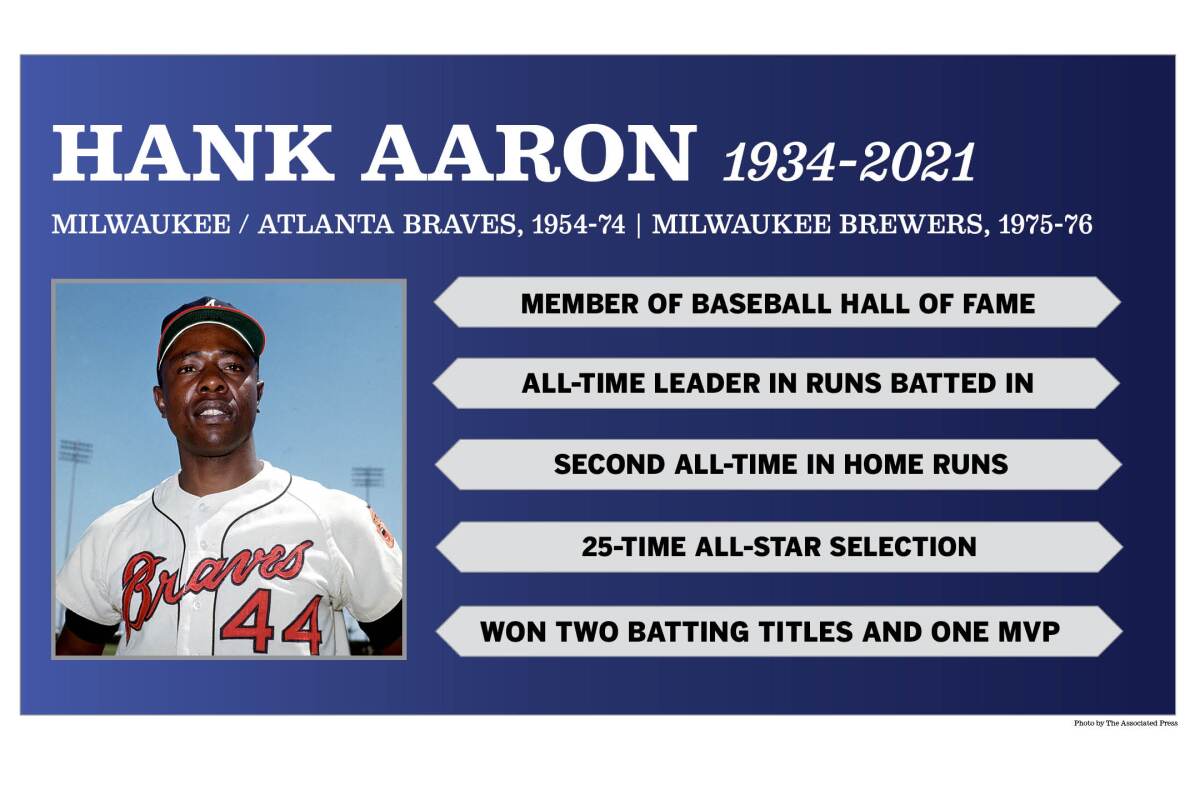

Hank Aaron dies at 86; legendary ballplayer broke Babe Ruth’s home run record

At what should have been the pinnacle of his long career in baseball, Henry Aaron was getting bags of hate mail — many containing death threats — and living in a storage room at the stadium, accompanied by bodyguards when he ventured out.

It was 1973, the country remained divided along racial lines, and Aaron, a Black player for the Atlanta Braves, was closing in on Babe Ruth’s holy career record of 714 home runs. To some, it was sacrilegious that a Black man would threaten the record of the immortal Babe.

Aaron eventually tied, then surpassed Ruth’s record, finishing his remarkable 23-year career with 755 homers. Even at that, he felt shortchanged.

“This was supposed to be the greatest time of my life,” he said. “They cut a piece of my heart out. Babe Ruth never had to contend with anything like that when he was establishing his record.”

And although his record was broken during the steroid era in 2007 by Barry Bonds, who finished with 762 homers, Aaron is viewed by most baseball purists as the legitimate record holder.

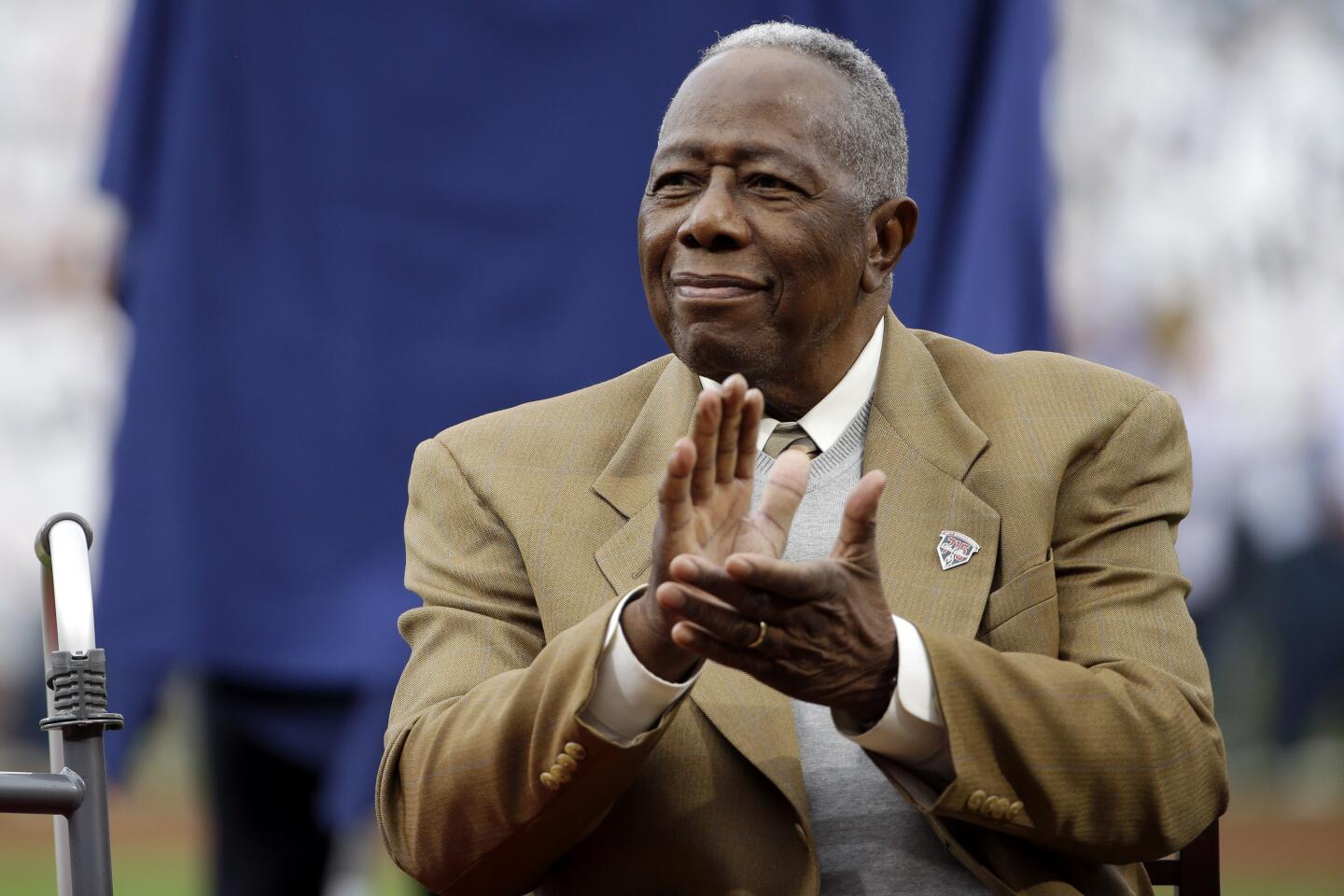

Long regarded as one of baseball’s true titans, Aaron died Friday at age 86, according to the Braves. A cause of death was not immediately known; the Braves released a statement saying Aaron “passed away peacefully in his sleep.”

“His monumental achievements as a player were surpassed only by his dignity and integrity as a person,” Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred said. “Hank symbolized the very best of our game, and his all-around excellence provided Americans and fans across the world with an example to which to aspire.”

Former President Obama called Aaron an inspiration. “Hank Aaron was one of the best baseball players we’ve ever seen and one of the strongest people I’ve ever met.”

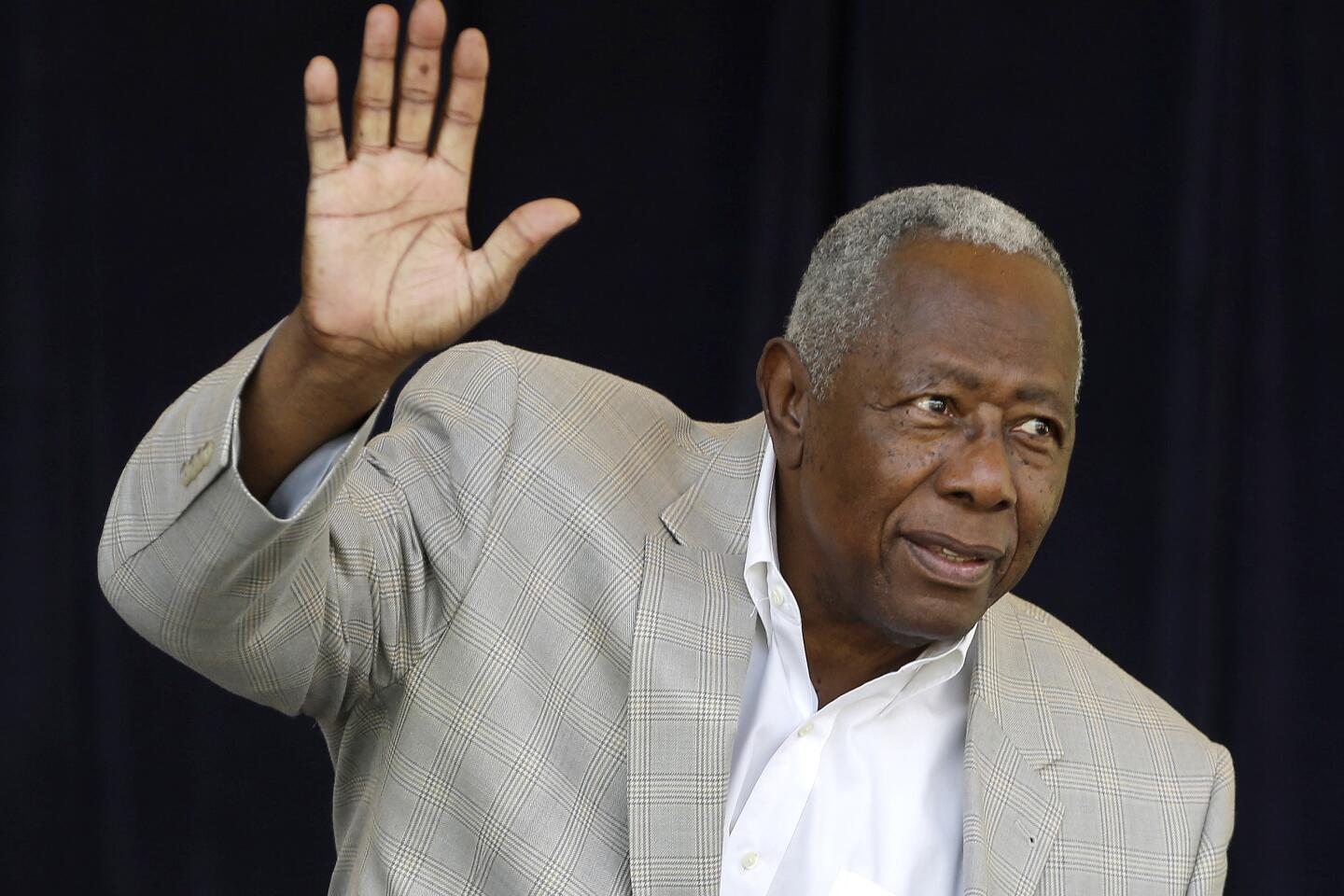

After his playing career ended in 1976, Aaron embarked on a successful second career as a businessman and philanthropist. He also was a clear and authoritative voice in the civil rights movement.

“We are absolutely devastated by the passing of our beloved Hank,” Braves chairman Terry McGuirk said in a statement. “He was a beacon for our organization first as a player, then with player development, and always with our community efforts. His incredible talent and resolve helped him achieve the highest accomplishments, yet he never lost his humble nature.

“Henry Louis Aaron wasn’t just our icon, but one across Major League Baseball and around the world. His success on the diamond was matched only by his business accomplishments off the field and capped by his extraordinary philanthropic efforts.

“We are heartbroken and thinking of his wife Billye and their children Gaile, Hank Jr., Lary, Dorinda and Ceci and his grandchildren.”

Bonds, who had become a prodigious hitter with the San Francisco Giants, was accused of using illegal steroids toward the end of his career, when his muscle mass and home run production jumped dramatically. In April 2011, he was found guilty of obstructing justice for impeding a grand jury investigation into illegal steroid distribution, but a federal appeals court overturned that conviction in 2015. Baseball conducted its own investigation into steroid use but has not altered the statistics of known or suspected steroid users, though — despite his gaudy statistics — Bonds has not been elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

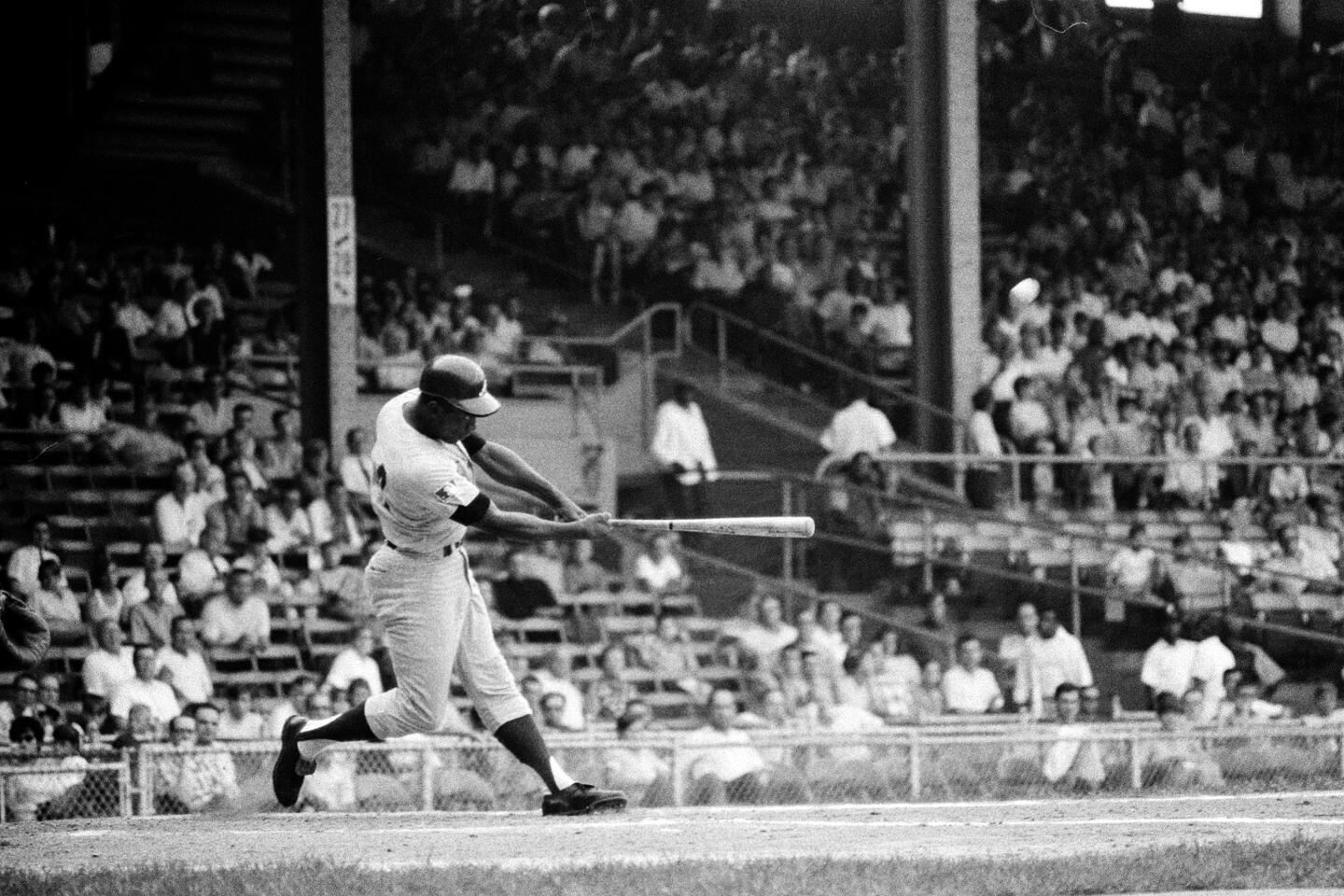

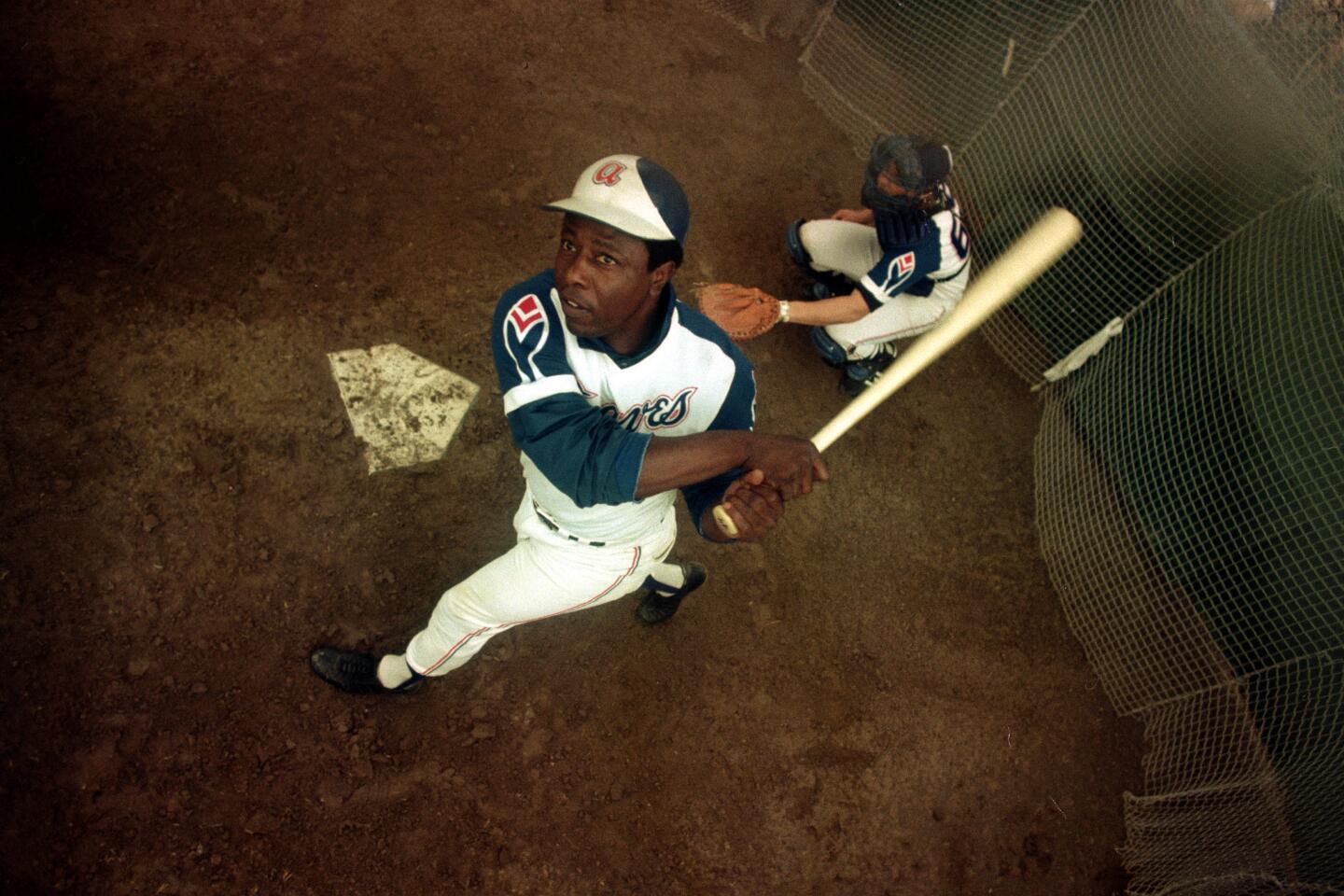

The Bonds issue, however, loomed as another example of Aaron’s difficult relationship with baseball’s ultimate weapon, the very thing that made him — late in his career — famous. Largely self-taught and, at 6 feet and 180 pounds, the antithesis of the popular image of a slugger, Aaron never hit more than 47 homers in a single season.

A quiet man playing in understated Milwaukee and Atlanta, Aaron longed to be recognized as a complete ballplayer, one who could reach base, steal, field and throw out runners from the outfield. His peers, of course, knew all about that, but the flamboyant Willie Mays was doing all those things too, and doing them with flair — losing his cap, making basket catches, diving for balls that were routine outs — and doing them on the grand stage that is New York, and later San Francisco.

Even as a home run hitter, the young Aaron was often overshadowed by Mays, Stan Musial, Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris. Occasionally his own teammates, such as Eddie Mathews and Joe Adcock, seemed to steal the show. They hit towering blasts, the kinds of home runs that everyone in the stands knew were out of the park the moment bat met ball. The slender Aaron, getting his power from his quick wrists and sinewy forearms, hit ropes — rising line drives that cleared infielders’ gloves by a few feet but landed halfway up the bleachers. They were gone before anyone had a chance to admire them.

And when, finally, the sporting world recognized that he was a bona fide home run hitter, as he approached Ruth’s record, Aaron had to endure a still-intolerant America.

For most of the 1973 season, as he closed in on the record, instead of staying with the rest of the team on the road, Aaron roomed in another hotel, alone, registered under an alias. And in Atlanta, instead of living at home, he bunked in an old storage room in Atlanta Stadium, where teammates brought him food. At one point, FBI agents were dispatched to Fisk University in Nashville, where his daughter’s life had been threatened.

Barry Bonds, Magic Johnson, Stacey Abrams, Barack Obama, Vin Scully and Mike Trout are among those remembering baseball great Hank Aaron, who has died at 86.

Through it all, Aaron persevered, and when he had finally surpassed Ruth’s mark, he said, “I don’t want them to forget Ruth. I just want them to remember me.”

Hard to forget, actually. For all the home run hoopla, Aaron was, indeed, a complete player, the National League’s most valuable player in 1957, three times a Gold Glove right fielder and 21 times an all-star. He helped the Milwaukee Braves to a World Series title over the New York Yankees in 1957 and was a key component when the Braves made the Series again in ’58, this time losing to the Yankees. He finished his long career with a .305 batting average, 3,771 hits and 2,297 runs batted in, the major league record — again well ahead of Ruth. Aaron also holds the record with 6,856 total bases.

“As far as I’m concerned, Aaron is the best ballplayer of my era,” Mantle once said. “He is to baseball of the last 15 years what Joe DiMaggio was before him. He’s never received the credit he’s due.”

Primarily, though, Aaron was a natural-born hitter. He led the league four times in home runs, four times in RBIs, three times in runs scored, twice in hits and twice in batting average. Still, he never won the triple crown — leading the league in homers, batting average and runs batted in during a single season — and that bothered him.

“I look back on all the things I accomplished and I wish I could have concentrated a little more on winning the triple crown,” he said. “I was either short on homers or batting average. I had two or three chances to do it. That’s the only thing I regret.”

Aaron seldom got good pitches to hit. Pitcher Curt Simmons of the Philadelphia Phillies observed, “Trying to throw a fastball by Henry Aaron is like trying to sneak a sunrise past a rooster.”

To the fans, he was “Hammerin’ Hank.” To other ballplayers, he was “The Hammer.” And to pitchers, he was “Bad Henry.” Yet it wasn’t until the 1970s, well into his Hall of Fame career, that Aaron began drawing more than casual notice. Somebody looked at Ruth’s homer total, then at Aaron’s, considered Aaron’s durability and concluded that he might very well surpass it. Suddenly, the spotlight was on Aaron, and with each succeeding home run it glared brighter.

At the start of the 1973 season, Aaron had 673 homers, 41 short of the record. Six times in his career he had hit more than 41 in a season and as recently as 1971 had hit 47. If he had a normal season, stayed healthy and injury-free, the record, it seemed, was his for the taking.

It was hardly a normal season, though. Public interest grew across the nation, and although most of it was positive, some was ugly. According to the Braves, Aaron received about 900,000 pieces of mail during his record pursuit, 100,000 of them expressing hate. Aaron advised teammates not to sit too close to him in the dugout.

“Hank used to show them to us,” Dusty Baker, Aaron’s protege and the current manager of the Houston Astros, said of the threatening letters. “People have got to share stuff with somebody.”

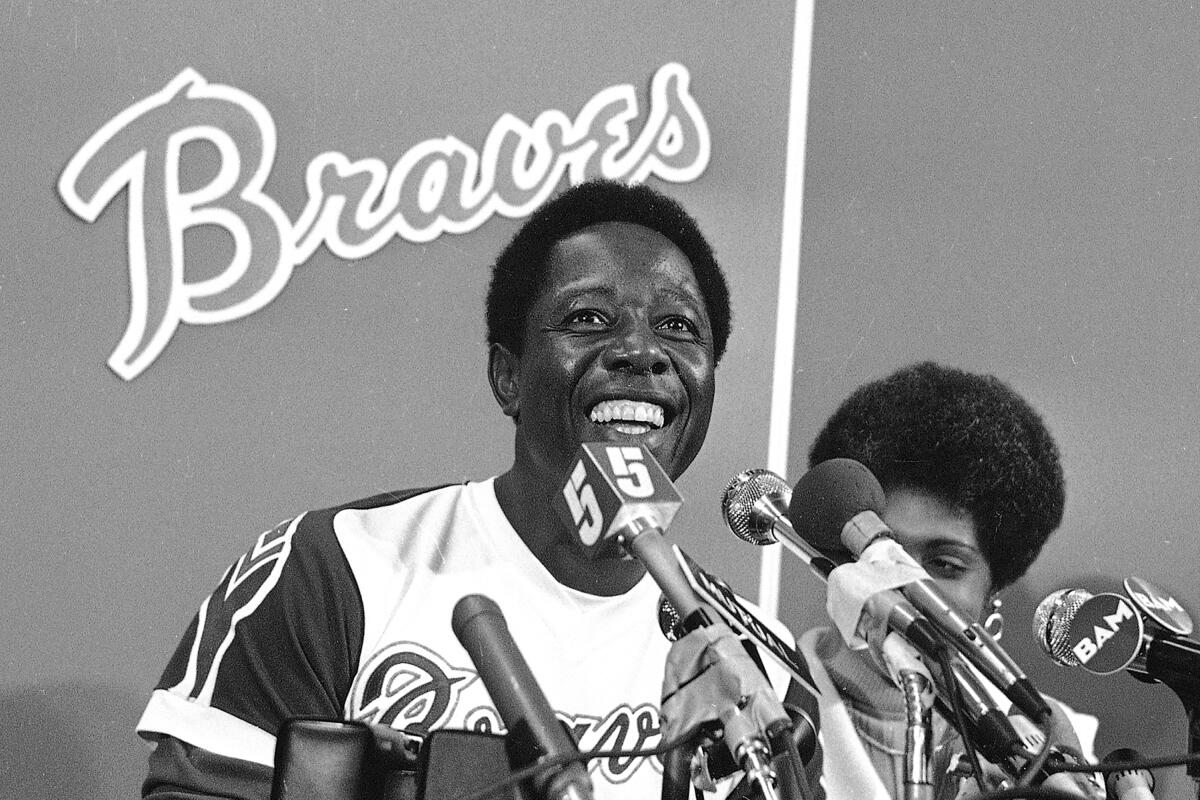

“I don’t know how many nights he played under death threats,” Johnny Oates, another Braves teammate, told Florida’s St. Petersburg Times. “But he would go out and play and stay on an even keel. And he always kept that great smile. He showed unbelievable class.”

Despite the threats, the media attention, the inconvenient living accommodations, Aaron had, by any standard, a solid season. He hit .301 and drove in 96 runs. His 40 homers, though, left him one short of the record, prolonging the agony until the 1974 season, which came with problems of its own.

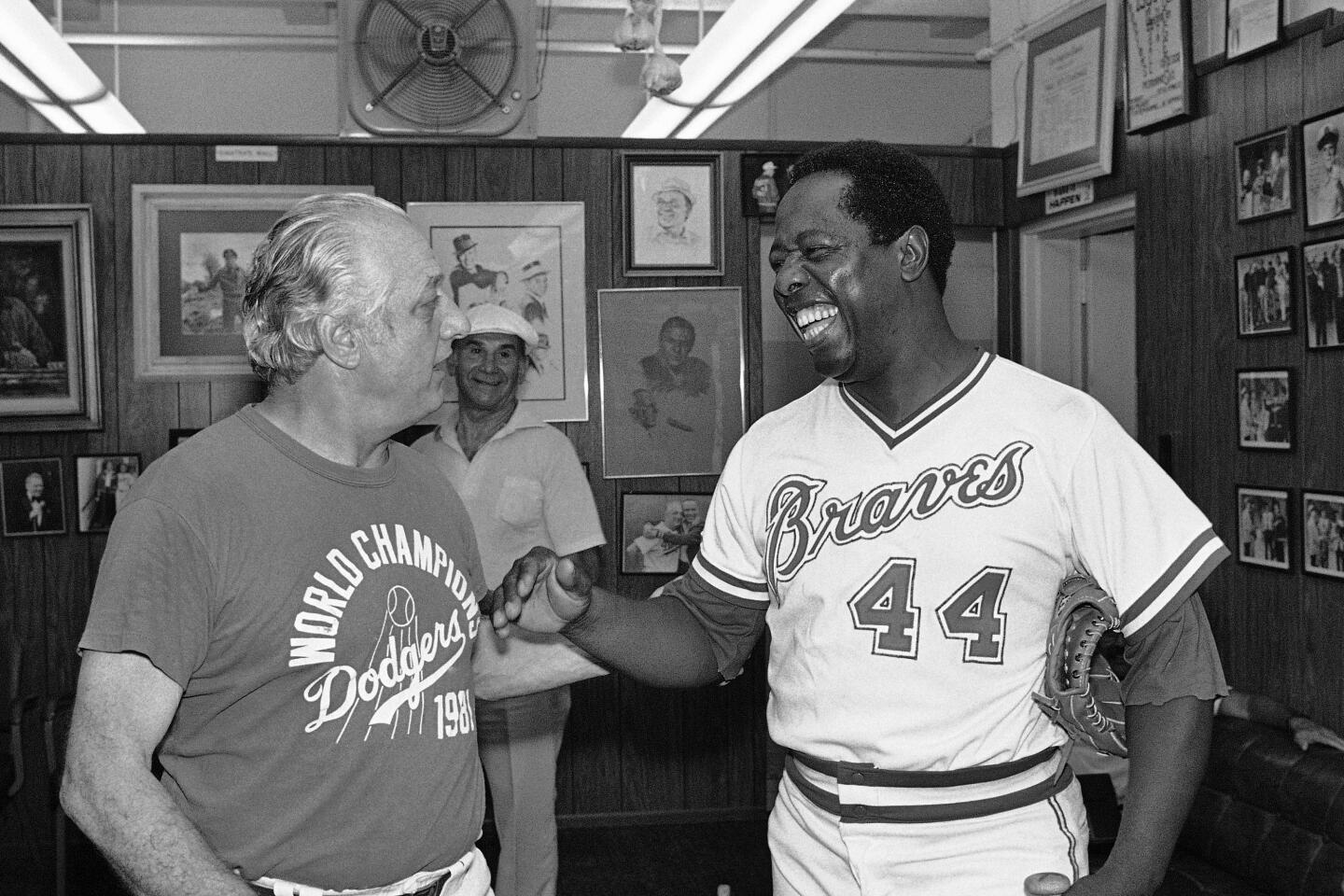

Mathews, Aaron’s former teammate and by then his manager, said he intended to keep Hank out of the lineup in the season-opening three-game series at Cincinnati so that Aaron would have the opportunity to tie, and possibly break, Ruth’s record in front of Atlanta fans in a home-opening series against the Dodgers.

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, ruling that such lineup manipulation would mar baseball’s integrity, ordered Mathews and the Braves to play Aaron at Cincinnati, or face suspension.

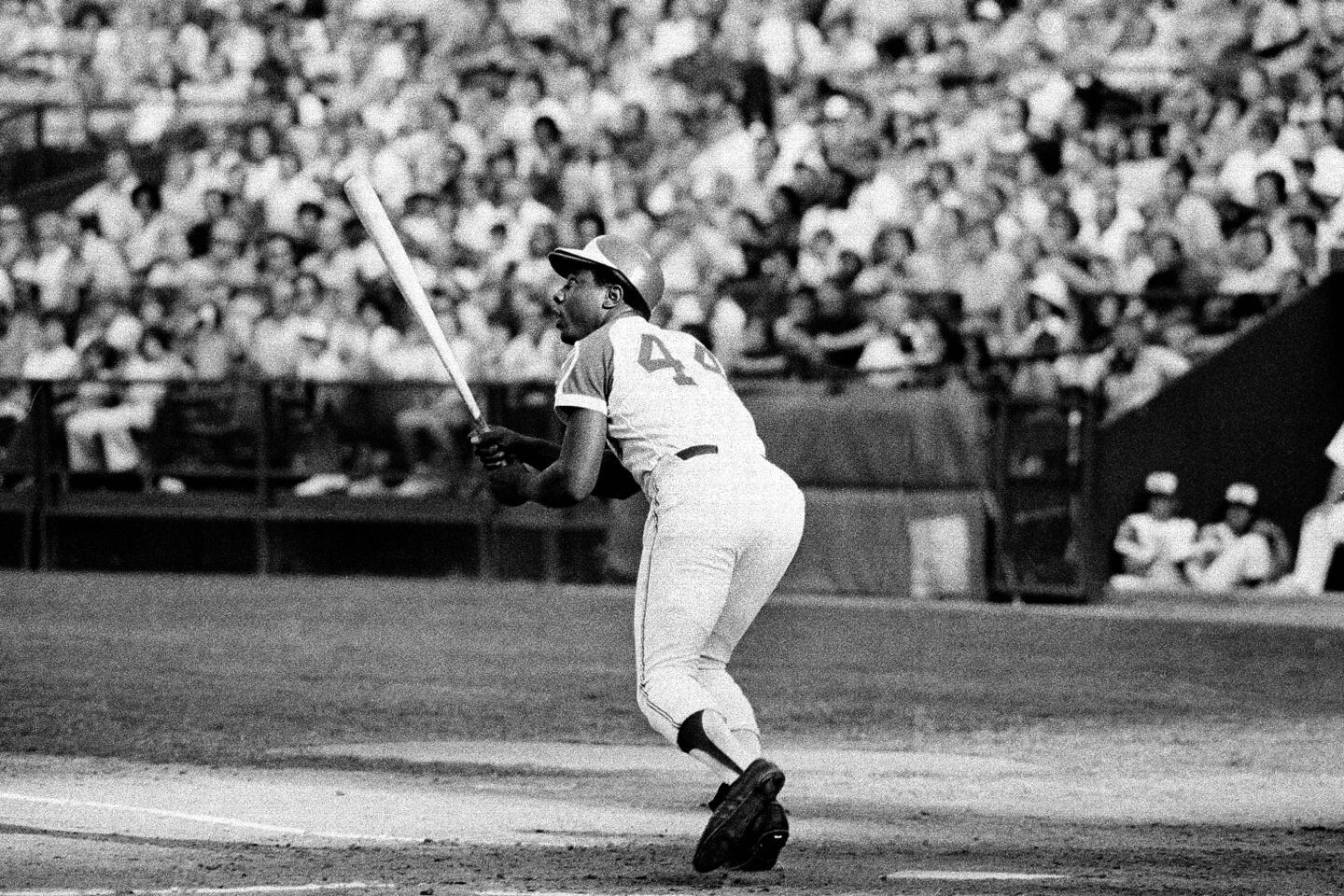

So Aaron played, and immediately took care of business, hitting No. 714 on his first swing of the season against Jack Billingham. He finished that game, sat out the next, then, again at Kuhn’s order, played the third and was hitless.

And then the Braves went home to play the Dodgers. The stadium was full on the evening of April 8, 1974, but Kuhn, who was speaking to the Wahoo Club, an Indians’ booster club in Cleveland, was not among the 53,775.

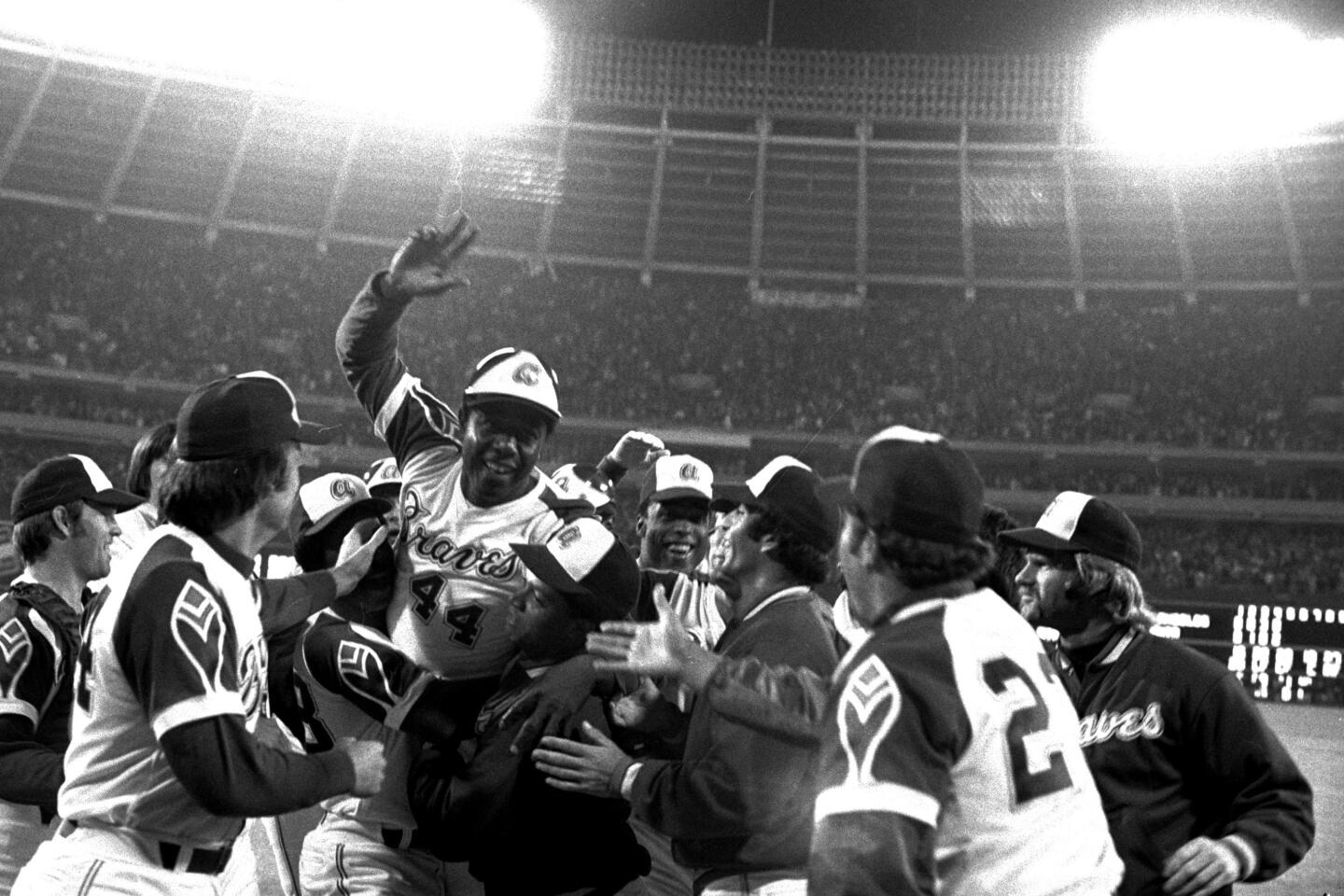

Aaron didn’t miss him. And he didn’t miss No. 715.

His first time up, against pitcher Al Downing, he walked without swinging the bat.

Then in the fourth, with a runner on first, Aaron turned to Baker, who followed him in the batting order, and said he was going to get it over with.

On Downing’s 1-and-0 pitch, he hit one of his typical rising line shots. Bill Buckner, the Dodgers’ left fielder, made a leaping, climbing stab at it but missed as the ball sailed over the fence, into the Braves’ bullpen and the glove of relief pitcher Tom House.

Vin Scully, the legendary Dodger broadcaster, called the play:

“It’s a long drive to deep left, Buckner to the fence. [Pause] It is gone!”

Scully went silent, letting the roar of the crowd wash over the airwaves, and then said, “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

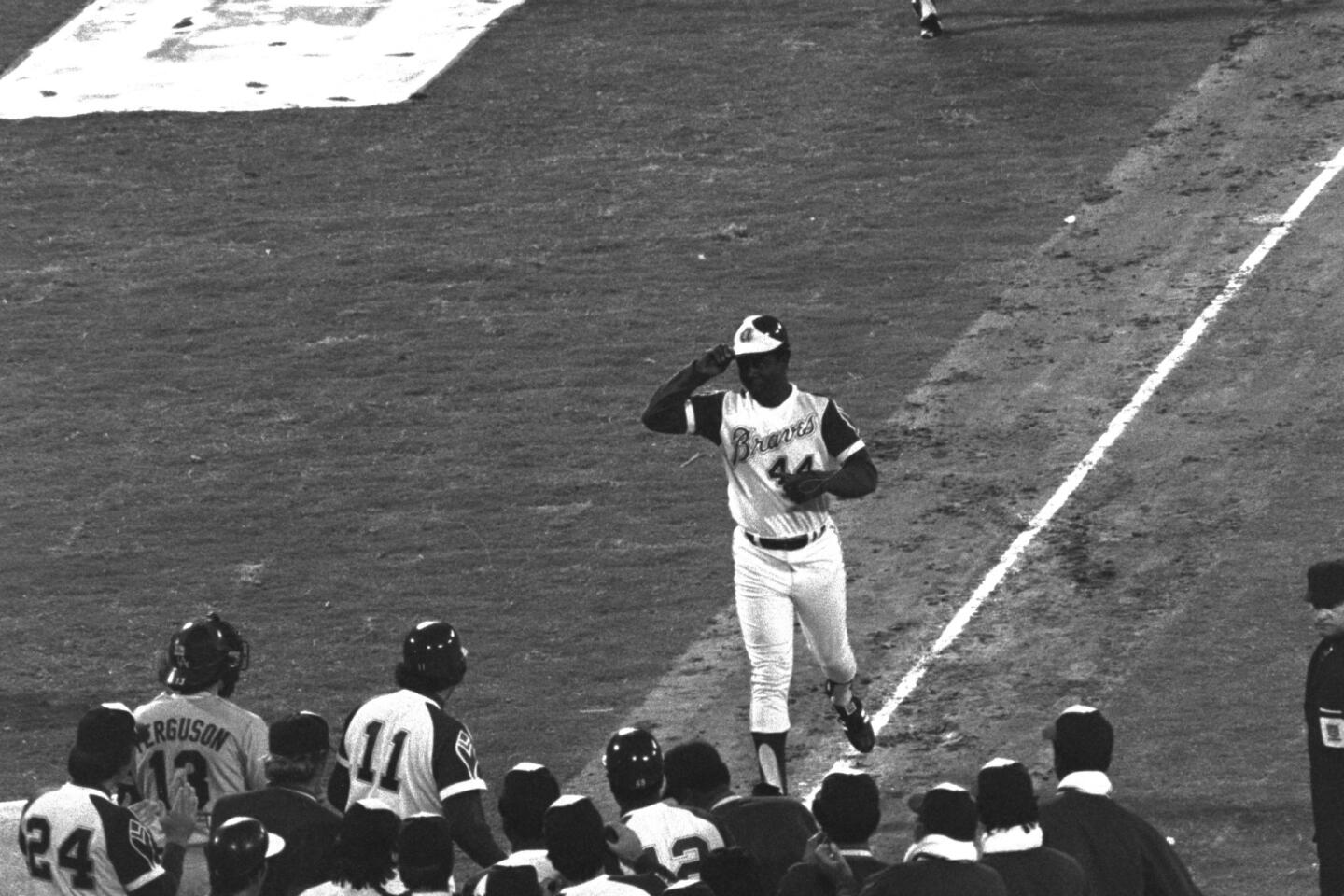

During his home run trot, Aaron got handshakes from several Dodgers and was joined by two overeager fans during part of his journey. He was greeted after crossing home plate by his mother, Estella, who hugged him in a fierce embrace.

Aaron was more relieved than happy, saying he felt that “the weight of a stove” had been taken off his shoulders.

By then 40, Aaron hit only 18 more home runs that season, then was traded to the Brewers, a struggling team in a Milwaukee market still soured by the Braves’ move to Atlanta. The Brewers needed a drawing card, and Aaron fit the bill nicely for two seasons, ending his big league career where he’d long ago started it.

go started it.

Henry Louis Aaron was born Feb. 5, 1934, in a segregated neighborhood in Mobile, Ala., the son of a shipyard laborer, the third of Herbert and Estella Aaron’s eight children. Hank’s younger brother Tommie also became a major leaguer. As youngsters, Hank, Tommie and friends played their version of baseball, using mop and broom handles as bats, bottlecaps as balls.

With no formal coaching, Aaron grew up batting cross-handed, not that it much mattered. He still was a fearsome hitter who, as a teenager, was playing for the Mobile Black Bears, a semipro team that paid him $10 a game.

Jackie Robinson had broken organized baseball’s color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, and by the ’50s, Black players were scattered throughout the major leagues. The Negro Leagues were still around, though, and in 1951, a 17-year-old Aaron, with a suitcase, two sandwiches and $2 from his mother, took a train from Mobile to Indiana, where he began his professional career with the Indianapolis Clowns.

His hitting there caught the attention of a Braves scout. The Braves paid the Clowns $10,000 for his rights, signed him and sent him to their minor league club in Eau Claire, Wis., where he finally was shown the proper way to grip a bat. It helped, too, for he batted .336 and was the Northern League’s rookie of the year in 1952.

He was sent to Jacksonville, Fla., of the South Atlantic League in ’53, one of only five Black players in a league that played in the still-segregated Deep South. He was unable to eat in restaurants or stay in hotels with his white teammates and was subjected to taunts and racial slurs, not only from fans but fellow ballplayers as well. He dealt with it all in the way he knew best, batting .362 with 22 home runs and 125 RBIs, earning the league’s most valuable player award.

He went to spring training with the major league club in 1954 and, after having played in the infield all his life, was moved to the outfield. That turned out to be a fortuitous shift.

The year before, the sad-sack Braves had moved from Boston to Milwaukee, where they promptly became not only the toast of the town but the most surprising team in baseball. In Boston in ’52, the Braves, playing a scratchy second fiddle to the Red Sox, had finished 64-89, seventh in an eight-team National League, drawing fewer than 500,000 fans. In Milwaukee the next season, they drew nearly 2 million delirious fans and finished 92-62, second to the runaway Dodgers, then still in Brooklyn.

During the winter, the Braves added another player they hoped would get them over the hump and into the World Series, right fielder Bobby Thomson, who’d hit “the shot heard ’round the world,” the home run that gave the 1951 New York Giants the National League pennant in a playoff series with the Dodgers.

When Thomson broke an ankle in spring training, the Braves turned to the young, untested Aaron. They never had cause to regret it.

After playing out his string with the Brewers — they paid him $240,000 his last season, the most he ever earned as a ballplayer — Aaron returned to Atlanta, where he held numerous positions in the Braves’ front office. He also became a successful businessman, operating doughnut shops, chicken restaurants and car dealerships, and spoke out often for Black advancement in baseball and business.

Angels general manager Perry Minasian spent time with Aaron while serving as an assistant GM for the Atlanta Braves from 2017 until 2020. He opened a conference call Friday related to the Angels’ signing of pitcher José Quintana with this:

“Baseball as a world lost someone today who was really special: Hank Aaron. Being around him the last three years and having the ability to talk to him, pick his brain — I get goosebumps just thinking about him walking in the room telling stories, just what he went through, and the class, the dignity, the humility.”

Aaron spent much of his time as a philanthropist. President George W. Bush presented him with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2002 for his humanitarian efforts, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund awarded him the Thurgood Marshall Lifetime Achievement Award in 2005 and established the Hank Aaron Humanitarian in Sports Award.

Aaron and his wife, Billye, began the Hank Aaron Chasing the Dream Foundation in 1994. It set out to award scholarships to 755 recipients, a number equal to Aaron’s home run total, although that has since been far surpassed.

The foundation has since been transformed into the “44 Forever” program, which honors Aaron’s jersey number, runs in perpetuity and provides 44 members of the Boys & Girls Clubs of America scholarships worth up to $2,500 apiece each year. Aaron also launched the “4 for 4” foundation in 2010, which provides 12 scholarships a year to students from underrepresented groups.

“Billye and I have been blessed with a great many friends who were there for us during our lives and now join us in our efforts to help young people become more than even they can imagine,” Aaron said. “It is so rewarding to know that children will continue to benefit from 44 Forever and 4 for 4 long after we are gone. We hope they will remember us for this work, not just for the records I set on the field.”

He politely stayed out of the Bonds controversy for years, then finally told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2009 that Bonds was the record holder and should be recognized as such. Occasionally, however, he expressed disappointment at how his breaking of Ruth’s record was sometimes downplayed.

“Funny how Babe Ruth’s 714 home runs was the most impressive, unbreakable record in sports until a Black man broke it,” he told Sports Illustrated.

Aaron was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, getting 97.8% of the votes in the first year he was eligible. Statues of Aaron were erected outside Miller Park, the Brewers’ home ballpark, and Turner Field, where the Braves played until 2016.

Aaron is the 10th Hall of Fame member to die since April: Al Kaline, Tom Seaver, Lou Brock, Bob Gibson, Joe Morgan, Whitey Ford and Phil Niekro died in 2020. In addition, Tommy Lasorda died Jan. 7 and Don Sutton died Jan. 19.

He is survived by his second wife, Billye Williams Aaron, and Ceci, their daughter, as well as children from his first marriage to Barbara Lucas, sons Hank Jr. and Lary, and daughters Gaile and Dorinda. Another son, Gary, Lary’s twin, died in infancy.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer. Times staff writer Maria Torres contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.