The low-slung stadium in Inglewood shimmers amid palm trees and parking lots and a six-acre artificial lake, an artist’s rendering finally brought to life.

Rams owner Stan Kroenke poured six years and at least $5 billion into the 3.1-million-square-foot building that looks as if it arrived from another world.

SoFi Stadium’s swooping lines are an homage to the curves of California’s coast. Much of the asymmetrical roof is transparent, using ETFE panels that are as clear as a windshield and strong enough to support an auto.

Perforated aluminum triangles — the pattern on each is unique — form the skin of roof, bordering the transparent portion and changing colors with the sun.

The sides of the stadium are open to the elements, allowing breezes to flow past 38 massive blade columns that support the building. The field is sunk nearly 100 feet into the ground.

Everything seems to be on an amplified scale. There’s the 120-yard halo-shaped video board suspended above the field, the 2 1/2-acre open-air plaza and 6,000-seat performance venue that share the same roof as the stadium, the canyons where patrons descend into the structure that are themed with indigenous flora and fauna from different regions of California.

“It’s iconic,” said Jerry Jones, the Dallas Cowboys owner and Los Angeles native who played a key role in pushing the ambitious project forward. “I’ve tried to run from the word. But this stadium, there was no way Stan was going to cut costs in any way that would compromise the overall, long-term sense of quality or value. It needs to be like Mt. Rushmore.”

Times NFL writer Sam Farmer gives a tour of SoFi Stadium, the new home of the Rams and Chargers.

The privately financed stadium is the centerpiece of a 298-acre development that’s three times the size of Disneyland. Plans call for the site where the Hollywood Park racetrack operated for 75 years to eventually be filled with millions of square feet of retail, restaurants, office space, residences and parks.

Everything revolves around the 70,240-seat stadium, the most expensive built in the U.S., if not the world, and the biggest created for football.

But the sweeping grace of the edifice stands stark in contrast to the difficulty in transforming the vision into concrete-and-steel reality.

“For all the twists and turns over the past five years, SoFi Stadium and Hollywood Park are exactly the vision laid out in 2016,” said Kevin Demoff, chief operating officer of the Rams.

There was the sharp-elbowed competition between the Rams and Chargers, who will share the stadium, for the right to return the NFL to Los Angeles after the league’s two-decade absence. The record rainfall that delayed the building’s opening by a year. The ballooning price tag. The deaths of two construction workers. The novel coronavirus outbreak that infected dozens of workers and wiped out carefully orchestrated opening plans. Until further notice, the public will be able to see SoFi Stadium only from a distance.

Building a stadium isn’t easy.

===

As a developer, Stan Kroenke gets some of his most productive thinking done before sunrise. It was on one of those mornings, behind the wheel of an SUV in summer 2013, that he took his first long look at Hollywood Park.

“That’s the best time because the traffic isn’t out, so you can get around quickly,” Kroenke told The Times in 2016. “I started looking at different sites to make sure I had them in my head. What do they look like? What could be done? How does the long term look for the areas? And when you drive up to Hollywood Park, it’s a great site.”

He knew the lay of the land in Inglewood, and he knew about the Hollywood Park site, which the NFL already had approved in the early 1990s when legendary Raiders owner Al Davis wanted to build there. But Kroenke wanted to get a better look at the place that was still a racetrack, and wouldn’t be demolished for two more years.

Excited about the potential of the location, Kroenke called his top Rams executive at team headquarters in St. Louis that morning.

“There are moments in your life you’ll never forget,” Demoff said in 2016. “I was standing by the window in my office and Stan called. ... I remember he said, ‘This is an unbelievable site.’”

A team-by-team look at the NFL team owners who collectively control football and the richest sports league in the world.

Seven months later, just before the Super Bowl between the Seattle Seahawks and Denver Broncos, Kroenke announced his purchase of 60 acres in Inglewood for about $100 million. The land was next to the Forum and wasn’t big enough for a stadium and parking. But it proved to be the gateway to the much larger Hollywood Park site, which was earmarked to become a mixed-use development.

Jones could see the bigger picture coming into focus. In August 2014, the Cowboys owner sat behind his desk, and across from a reporter, in his makeshift office — a converted room at the Courtyard hotel in Oxnard — as his players ran through training camp drills at the neighboring field complex.

For several years, Jones kept close tabs on the various stadium proposals and possibilities of the league reentering the L.A. market. Not only did Jones recognize the potential of the NFL’s return, but also he felt a deep connection to Southern California. He was born in L.A. in 1942, and his first home was on 112th Street, about 4 1/2 miles from what is now SoFi Stadium.

In this case, Jones understood the cast-iron will, steely nerves and financial means of Kroenke, listed last year by Forbes as the NFL’s second-richest owner, with an estimated net worth of $9.7 billion.

“I said, ‘Get your eyeballs attentive to this; this thing has got a lot of special parts to it,’” Jones recalled recently of the conversation with the reporter that took place six years earlier. “For the NFL, Stan was manna from heaven. I was convicted about that. I said it to the ownership: ‘Guys, we’ve got to look upstairs and thank Stan Kroenke for wanting to do this project for Los Angeles.’”

So many before Kroenke had tried. Dozens of billionaires, politicians, celebrities and power brokers had attempted to solve the L.A. riddle. No one was successful.

It defied logic, the nation’s No. 2 market without its most popular sport. Between 1995, when the Rams and Raiders left, and 2016, when the Rams returned, two franchises relocated and two more were formed.

The problem with L.A. was — unlike other cities around the country — there was no public money for a stadium nor any appetite to change that. Any venue would have to be paid for privately, and the deal wasn’t attractive enough for developers unless they had at least a piece of a team.

With luxury suites and club seats increasingly popular around the league, the aging Coliseum and Rose Bowl became increasingly outdated and unattractive, particularly without major renovations. Newer NFL stadiums are vertical, with the vast majority of seats located between the goal lines. Those gradual, contiguous bowls, with a large percentage of seats in the end zones, do not generate the kind of revenue that attracts NFL owners.

What’s more, during the period when L.A. was without a team, the widespread advent of the internet, NFL Network and DirecTV’s “Sunday Ticket,” which allows fans to follow their favorite team from afar, made consuming football from the couch much easier.

Still, there were ongoing efforts to develop a stadium, and reams of renderings of never-built, fantastical venues. From Irwindale to Irvine, the futuristic Farmers Field downtown to “The Hacienda” in Carson, a reimagined Rose Bowl, a doctored Dodger Stadium, the Platinum Triangle of Anaheim to the City of Industry ... all ran out of steam or money, or both.

The new SoFi Stadium will be home to the Rams and Chargers, but it holds the potential to be so much more to the communities around it.

During the period when L.A. was without a team, 27 NFL stadiums were either built or underwent at least $400 million in renovations. In many ways, L.A. was more valuable to the NFL without a team than with one. When a franchise was angling for money from its hometown or state to build a new stadium, it could use the threat of relocating to L.A. to change people’s minds and open their coffers. L.A. was the boogeyman.

===

In early January 2015, Kroenke publicly unveiled what had been in the works behind the scenes for at least a year and a half. He joined forces with the Stockbridge Capital Group, which planned a massive mixed-use development at Hollywood Park, to expand the project to include his 60 acres, a stadium and a performance venue. Kroenke eventually bought out Stockbridge’s share of the development.

“It’s something that’s going to be in place and in his family long after he’s gone,” Terry Fancher, the executive managing director of Stockbridge, said at the time. “He’s really looking at the long term. I’ve rarely run across someone whose main concern is, ‘I want the best we can have.’”

The path forward was bruising. A report by former secretary of Homeland Security Tom Ridge on behalf of AEG, which was still pursuing Farmers Field, suggested the Inglewood stadium’s proximity to L.A. International Airport created a “significant risk profile.” The report speculated that terrorists could try to shoot down a plane over the stadium or crash one into it as part of a “terrorist event ‘twofer.’”

(A subsequent risk analysis the NFL commissioned by Michael Chertoff, who followed Ridge as secretary of Homeland Security, found no unusual security risks for the venue.)

Six weeks after Kroenke’s announcement, the San Diego Chargers and Oakland Raiders revealed their joint pursuit of a stadium in Carson on 168 acres atop an old landfill.

The competing projects offered starkly different visions for football in L.A.: an open-air stadium, natural grass and immediate access to the 405 Freeway in Carson against the covered, artificial turf option in Inglewood that would be the engine of an enormous development.

The three-team race gathered speed. Inglewood’s City Council unanimously approved a ballot initiative to greenlight the stadium and bypass lengthy environmental review less than a week after the Carson plan was announced. AEG scuttled Farmers Field.

The Carson stadium design was revamped, including the addition of a cauldron where simulated lighting bolts would swirl when the Chargers played and a flame would burn in honor of the late Al Davis for their games. The signature elements were scrubbed from renderings presented to NFL owners four months later and a variety of features, such as a farmers market, were added.

Behind the scenes, Carson backers questioned the Inglewood stadium’s amount of parking, use of artificial turf, proximity to freeways and how the city would handle the influx of traffic on game days. Though civil in public, the competition played out through a series of presentations to NFL owners and executives, updated renderings, community outreach events and frequent media leaks.

“As great of a guy as [Chargers owner] Dean [Spanos] is, and as good a partner as he is, they have zero killer instinct,” one person involved in the saga wrote in an email in August 2015.

The Federal Aviation Administration raised concerns the Inglewood stadium could interfere with the radar directing air traffic at LAX. Kroenke eventually resolved them by paying $29 million to install a secondary radar system. The Chargers and Raiders hired then-Walt Disney Co. Chief Executive Robert Iger to oversee their stadium effort. Ridge sent a letter to Jerry Richardson — then owner of the Carolina Panthers and chairman of the NFL’s six-owner Committee on L.A. Opportunities — again raising safety concerns about the Inglewood stadium. Spanos rebuffed Kroenke’s overture to share the stadium.

Site preparation work continued at Hollywood Park in December 2015. A small yellow pipe stuck out of the dirt to mark the future site of the 50-yard line, amid heavy machinery and mountains of crushed concrete.

“This isn’t a small aspiration,” Chris Meany, development manager for the Hollywood Park Land Co., said at the time. “We are trying to do something that is grand and is appropriate for an international stage.”

===

NFL owners gathered Jan. 12, 2016, at the Westin Houston, Memorial City hotel. The league was determined at long last to decide how and where to return to L.A.

Although the NFL had reserved space for a two-day meeting, the owners were impatient. Four of the six owners on the L.A. committee had teams in the playoffs, and another was in the middle of a coaching search.

The meeting started with the Rams winning a coin flip, allowing them to present first. In the secured ballroom, Demoff pitched owners on Inglewood and a stadium that would be a crown jewel for the entire league.

He began the 25-minute talk with 30 renderings that showed the stadium and ended with excerpts from two columns by Bill Plaschke of The Times, pleading for the Rams to return.

“Together we make football,” Demoff said at the end of the pitch. “Together we make Los Angeles.”

Next up was Iger, among the world’s most powerful entertainment executives. He already knew most, if not all, of the owners. He extolled the virtues of the Carson plan, praising the location as ideal because it was next to the freeway and convenient to both L.A. and Orange County.

Sam Farmer gives an update on the stadium’s construction in December 2015.

Iger, who in his Disney role oversaw ESPN, spoke of his love of the NFL and his marketing expertise. He reminded the owners he had paid them plenty of money over the years.

When Iger finished and stepped out, Jones pushed away from the table in his swivel chair, stood and made an observation that drew chuckles from fellow owners.

“He said he paid us,” Jones said. “Last time I checked, that money is coming from Disney shareholders, not him.”

Clarity didn’t come quickly during the 11-hour meeting. Early on, the L.A. committee voted 5-1 to back the Carson plan, with Kansas City Chiefs owner Clark Hunt the lone dissenter. Word of that endorsement filtered from the secured fourth-floor ballroom to the third floor, where at least 200 media members were stationed to document the day.

In truth, the majority of owners were squarely behind the Inglewood plan, some reasoning the competition wasn’t close. Still, it was uncomfortable to give a fellow owner a public thumbs down, especially with the stakes so high. So it was a pivotal moment when owners voted 19-13 that L.A. should be decided by secret ballot.

A false narrative had taken root in some circles that Carson would win easily. But with the people who actually had a vote, the opposite was true. Among them, a consensus had solidified to pair the Rams and Chargers in Inglewood, and leave the Raiders in Oakland.

On the first ballot, owners voted 21-11 in favor of the Inglewood proposal, three votes shy of the 24 needed to pass. Strangely, the owners took a step backward in the second try, voting 20-12 for Inglewood. More discussions ensued. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell ushered the three owners seeking relocation into a separate room for a private negotiation that lasted an hour.

“As costs went up as dramatically as they did, the fact that Stan didn’t cut corners or reduce the scope of the project engendered a tremendous amount of goodwill from owners and league executives.”

— Marc Ganis, president and founder of the Chicago-based sports consulting firm SportsCorp

With a resolution within reach, Jones ordered beer and wine to be delivered to the ballroom. The hotel set up temporary bars.

When Goodell returned to the ballroom with the three owners, the Raiders announced they were withdrawing their bid to move. The new proposal was the Rams in Inglewood, with a team to be determined. That vote passed 30-2.

The Rams were heading back to L.A., and the Chargers had a one-year option to join them. If the Chargers were to decline, the Raiders would get the same offer.

Jones turned to his son, Stephen, the Cowboys’ top executive, and asked: “What did you learn today after seeing the process?”

“I learned one thing,” Stephen said. “If you’re going to get in the race, make sure you’re riding Secretariat.”

At an 8 p.m. news conference at the hotel, Goodell announced the decision while flanked by the three owners involved. The trio looked subdued and fatigued. Spanos read a short statement saying he would continue looking for solutions, then left the stage as Kroenke was making his comments.

“You know, I’m going to try to take a day off,” the dejected Chargers owner told reporters. “This has been really excruciating for everyone. I’m going to look at all our options. ... It’s very difficult to say right now, I’m going to do this or I’m going to do that.”

Both Joneses, along with Buffalo Bills owner Terry Pegula, had a celebratory dinner that night with Kroenke, Demoff and the rest of the Rams contingent. They ate at an upscale steakhouse next to the hotel, and Jerry Jones raised a glass of bourbon to toast the occasion.

To this day, Demoff has his room key from the hotel, a memento of that landmark meeting.

The next morning, the first day of a new era in the NFL, Kroenke stopped by Starbucks on his way to a private airport and picked up his breakfast: an egg sandwich and turkey bacon. He ate it on his jet, wiping away tears of joy as L.A. drew close. When the wheels touched down in Van Nuys, a new chapter was underway.

===

They broke ground 10 months later, Kroenke and Goodell and Inglewood Mayor James T. Butts Jr. wearing white hard hats as they plunged silver-tipped shovels with red bows into the soil at Hollywood Park the week before Thanksgiving.

“I don’t think people really understand the scale of this,” Kroenke said at the time.

But trouble lurked in an unexpected place. Millions of cubic yards of dirt needed to be excavated to create the giant bowl for the stadium. Between November 2016 and February 2017, however, the LAX area received 15.4 inches of rain. The frequent downpours left water 12 to 15 feet deep in the excavation site that at times resembled a lake. The water had to be pumped out each time and the area dried before work could resume.

“It was a very unforgiving two months for the project. And speaking from a building perspective, it really couldn’t have come at a worse time.”

— Bob Aylesworth, the principal in charge for the joint venture overseeing the project

In the midst of the rain, the Chargers exercised their option to relocate to L.A. and join the Rams in Inglewood in January 2017. During a welcome rally at the Forum a few days later, Goodell lauded the future stadium.

“It’s all about the vision of Stan Kroenke,” Goodell said.

The commissioner twice referenced the Rams owner — who wasn’t there — before mentioning Spanos or the Chargers.

Concern spread through NFL circles that the stadium project — already facing an aggressive schedule with little wriggle room to finish in time for the 2019 season — was falling behind. Developers finally announced in May 2017 that the stadium’s opening would be delayed by a year.

“It was a very unforgiving two months for the project,” Bob Aylesworth, the principal in charge for the joint venture overseeing the project, Turner-AECOM Hunt, said at the time. “And speaking from a building perspective, it really couldn’t have come at a worse time.”

The rain delay contributed to spiraling construction costs. Though the exact price tag for the stadium isn’t clear because the venture is private and infrastructure costs for the surrounding development are folded into totals, public estimates have increased from $1.86 billion to $2.6 billion to $5 billion. That includes the cost of acquiring land, debt service, design, building the NFL Media headquarters adjacent to the stadium — scheduled to open next year — and a host of other items.

The actual cost might be higher.

“There’s huge, huge risk, still, because you’re doing something at a cost no one has ever done before,” Kroenke said the week before the Rams played in the Super Bowl in February 2019. “We try to take the risk out of it, so we had independent cost estimates all along the way as we developed the stadium. The problem was ... those cost estimates by two independent people who worked with our architects on the costing were way off. They were just way off.

“So it takes a lot more investment, so that’s more risk. But we’re long term. ... We don’t get involved in things unless we think we’re going to be there for a long time.”

Stadium-related building permits filed with Inglewood through September 2019 are valued at about $2 billion, though the permits represent only a fraction of the project’s construction costs.

NFL owners in May approved the Rams borrowing an additional $500 million — believed to be a combination of a private loan to Kroenke and an increased debt limit for the franchise — to help finance the stadium.

“As costs went up as dramatically as they did, the fact that Stan didn’t cut corners or reduce the scope of the project engendered a tremendous amount of goodwill from owners and league executives,” said Marc Ganis, president and founder of the Chicago-based sports consulting firm SportsCorp. “Very few people in the country could have handled the additional debt without it being a strain. Stan is one of the few.”

The Chargers are $1-per-year tenants at the stadium and whose contribution to the construction costs are a $200-million G4 loan from the NFL, as well as revenue generated from the sale of seat licenses and 125 joint Rams-Chargers suites.

They also are paying a $650-million relocation fee to the league, as are the Rams.

In fall 2018, the Chargers announced their new home would feature more than 26,000 seats priced between $50 and $90 per ticket, plus a one-time personal seat license fee of $100.

By comparison, the least expensive Rams seat license is 10 times that. That pricing heightened tensions because it established an eyebrow-raising contrast between the clubs, and offered Kroenke little relief to offset construction costs. At the outset, both teams aimed to sell $400 million in seat licenses.

If the Chargers were to sell one-third of their seat licenses at $100, they would generate $2.6 million, a drop in the bucket for a $5-billion project, and leave Kroenke to shoulder more of the expense.

The novel coronavirus outbreak added another complication. A series of safety measures were put in place to protect construction workers, including additional bathrooms, mandatory temperature checks, social distancing, face coverings and requiring nonessential personnel to work from home. Eighty-one workers have tested positive for COVID-19 out of an estimated 4,000 on site since late March. None of the workers who tested positive has been hospitalized or died, according to the L.A. County Department of Public Health.

On June 5, an ironworker named Juan Becerra died after falling an estimated 110 feet from the stadium’s roof through a hole created by the removal of a panel for maintenance.

His wife and three young children sued Stadco LA, the company behind the stadium, Turner-AECOM Hunt and others in L.A. County Superior Court, blaming the fall on work being “unnecessarily and unsafely hurried” because of the pandemic.

Another ironworker, Simon Fite, died on the roof July 8 after the joint venture said he showed “signs of a health issue.” The L.A. County Medical Examiner-Coroner hasn’t released a cause of death pending additional investigation.

The plan to open the stadium with big-name concerts — starting with Taylor Swift in late July — evaporated because of the pandemic.

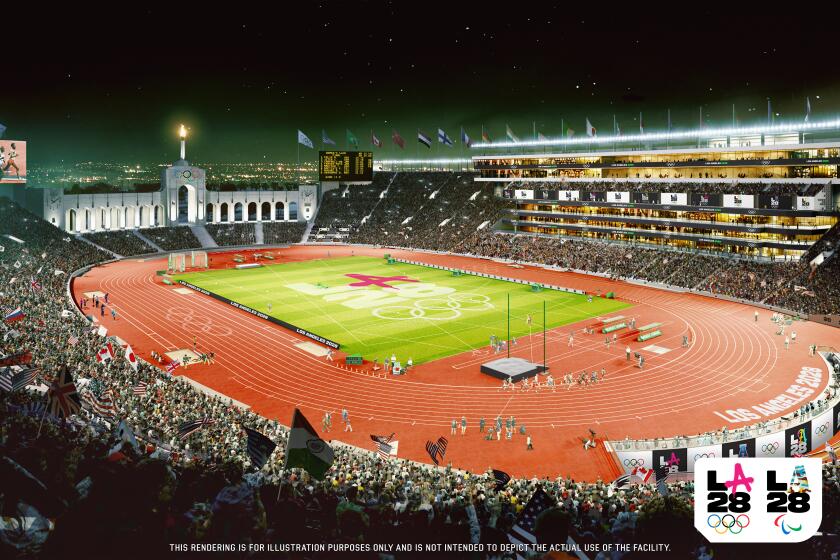

The NFL canceled its preseason too. The Rams, who open the stadium with a regular-season game against the Dallas Cowboys on Sept. 13, and Chargers announced fans won’t be allowed at the stadium until further notice. Among other marquee events, the stadium is scheduled to play host to the 2022 Super Bowl and the opening and closing ceremonies of the 2028 Summer Olympics.

When fans ultimately arrive, the ones with the most-expensive tickets will be able to stand at the bar in the SoFi Stadium Social Club and watch the news conferences through a glass wall that defrosts after the game.

At the top of the stadium, on Level 8, spectators can roam the massive indoor-outdoor concourses and, on a clear day, enjoy a vista that spans from the Hollywood sign and Santa Monica Mountains to Catalina Island.

“Every place in terms of your visual is unique in this building, because of the curvature of the roofline,” said Jason Gannon, managing director of SoFi Stadium and Hollywood Park. “That’s what’s really special about this, how Stan has been able to design something that does embrace Southern California.”

The scope of the project is staggering — 17.8 miles of cable, 144,000 cubic yards of concrete, a 2.2-million-pound videoboard (largest created), 12.5 miles of pipe ... all built through 12 million worker hours.

Some people appreciate the small details.

On his first visit to the stadium earlier this summer, Rams quarterback Jared Goff noticed that if he looked through the man-made canyon behind an end zone, he could see palm trees swaying in the breeze, a rendering turned reality.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.