Race and the NFL: A star-studded panel discusses social change, protests

It was a rare admission by the National Football League. In a video earlier this month, Commissioner Roger Goodell said the league was “wrong” for not listening to players earlier about inequality and police misconduct. He encouraged “all to speak out and peacefully protest.”

After the deaths of George Floyd and other Black Americans ignited protests and prompted renewed urgency in calls for societal change, numerous sports stars have committed to using their platform and fame to shine light on the issues.

Still to be seen is what the NFL might look like next season, and whether protests might evolve beyond quarterback Colin Kaepernick and a handful of other players taking a knee during the national anthem.

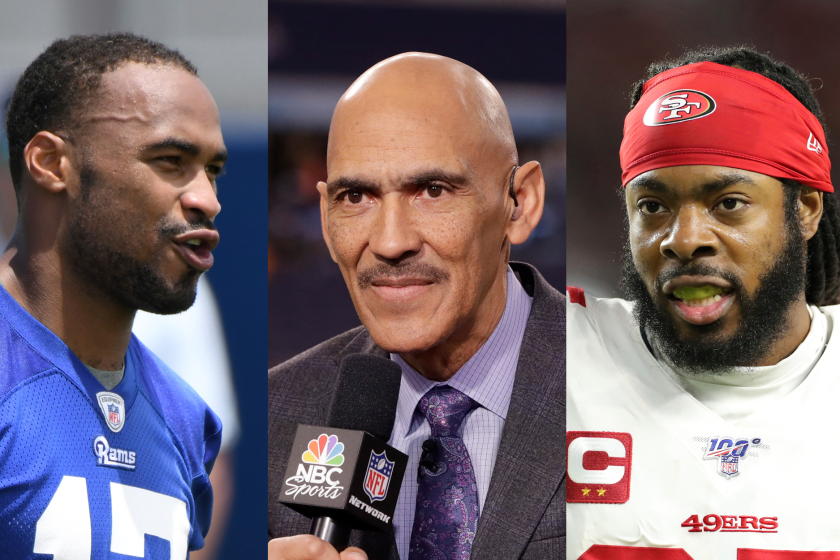

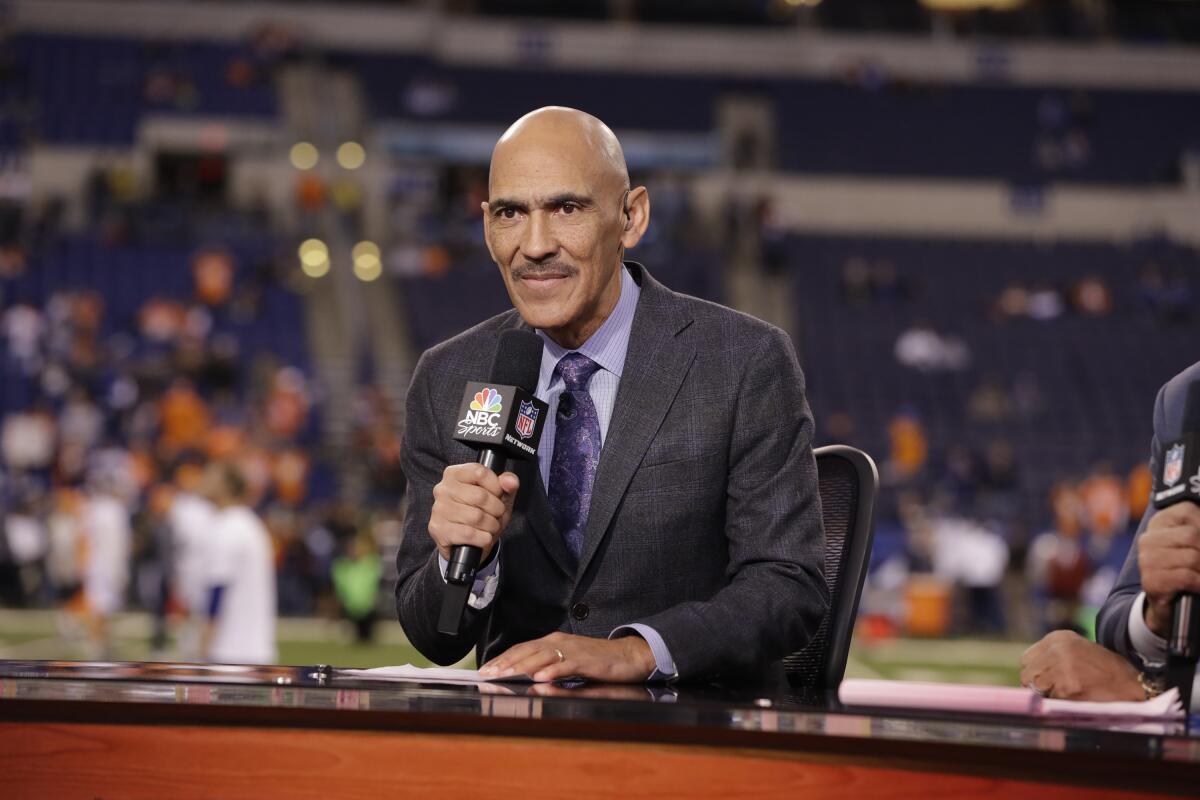

To discuss the situation, the Los Angeles Times formed a panel of Richard Sherman and Robert Woods, two star NFL players; Tony Dungy, a Hall of Fame coach; and LZ Granderson, a Times columnist who routinely writes about the intersection of sports, race and politics.

During a 35-minute Zoom teleconference Thursday, they discussed an array of topics related to racial and social justice issues, noting that the public is paying very close attention.

“I think what happened is people saw visually what they had been hearing about for a number of years,” said Dungy, who in 2007 became the first Black head coach to win a Super Bowl. “When you hear it, then your question becomes, ‘Did that really happen? Are there other things to take into consideration? Maybe it’s not exactly the way I heard.’ But seeing it visually has been so much different. I think this could be what actually ends up moving the needle.”

Richard Sherman, Tony Dungy and Robert Woods join The Times’ LZ Granderson and Sam Farmer to discuss social justice, racism and the NFL.

Woods, who grew up in Carson, starred at USC and is now a leading Rams receiver, agreed.

“It’s almost as if you couldn’t turn a blind eye to it,” he said. “It was everywhere. All over the news, all over social media. No sports going on. No concerts or activities. So this was all we were seeing, just information on injustice, police brutality, what was actually going on.

“You have people who had time, were able to go out and protest, not being able to work. They were actually able to stand for the cause and for the reason.”

That all resulted in what might have been a moment becoming a movement.

“The country and the globe essentially shut down because we needed to prepare ourselves to deal with a virus that was going to quite possibly threaten society,” Granderson said. “And we thought the virus was coronavirus, but it’s actually racism. Racism is the virus that’s been killing us much longer than coronavirus.

“The question is, how do we keep the white Americans who may have thought it wasn’t as serious, who may not have felt this was their fight, to stick with the fight? That is how you keep this element of the momentum going, by having white athletes, white owners, white executives, white CEOs realizing this isn’t something you write a check for and then move on.”

Dungy added: “We’ve had video of incidents like this in the past, but life was going on. Everybody would see it and say, ‘Oh, that’s a shame,’ and then go back to work, go back to what they were doing. But for [months] now we haven’t been able to do that. We have been arrested, so to speak.

“It’s going to be people who see this, who think about it, who react and say, ‘You know what, we do have to do something.’ And it’s got to be a heart change.”

In the past, Woods said, many players were circumspect about protesting because of possible repercussions. Kaepernick lost his job over it, but lesser known was that Denver Broncos linebacker Brandon Marshall lost sponsorship deals after similarly taking a knee during the anthem. However, the climate has changed.

“Now you see it as a sacrifice for athletes,” Woods said, “where it’s, ‘Let’s all take a stand.’… It really involves every single person.”

The situation prompted Granderson to think back to the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, where two Black Americans protested with raised fists on the medal stand.

“We know all about John Carlos; we know Tommie Smith,” Granderson said. “But it’s important that we talk about Peter Norman too; the white guy who was there. He also sided with those two brothers. He also went back home to Australia and had a very difficult time being re-assimilated into society. He was ostracized.

“Where are the Peter Normans who are willing to stand with their brothers and sisters in this and stick with it no matter what the costs may be? That’s an important element to all of this, whether or not the imagery of seeing white people marching resonates with people or not, the reality is, as far as I’m concerned, it lets me know that you know exactly what we’re fighting for, what this is about, and it isn’t just helping other people. This is something that’s helping you too. You’re a part of this.

By speaking up about Juneteenth, Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw underscored the importance of white athletes taking a stand that Black lives matter.

“What did Dr. [Martin Luther] King say? We came on different ships, but we’re all in the same boat now. That’s what this is.”

The panel was asked what NFL players and coaches can do to assure racial issues don’t fade into the background when play resumes.

“I would have taken part of my press conferences on Mondays and said, ‘I’m going to turn this over to my players. They have some concerns. I want to give them a voice and let them be heard,’ ” Dungy said. “I think that’s what we have to do is come together and discuss it. If I were the president of the United States, I would not just shut everything down. I would say, `We’ve got some young, intelligent, impressive men of influence, and they feel like something’s wrong. I need to invite them, listen to them, see what’s on their mind, see what solutions they have, and see if we can come together on this.’”

At a 2017 political rally, President Trump challenged NFL owners to fire any player who took a knee during the playing of the national anthem. He said the owners should say: “Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out! He’s fired. He’s fired!” That reignited the anthem protests which had largely dissipated by the end of the previous season.

Sherman, who played for the Seattle Seahawks at the time, said his coach, Pete Carroll, “pretty much did what Coach Dungy said he would do. He stopped us — it was before we played the Tennessee Titans — put us all in a room… He asked us, `What do we want to do?’ Because there were a lot of group texts going on between various teams throughout the league. There were conversations going on between us and the Titans, ‘Are we going to do something united?’”

Jeanie Buss shared on Instagram a letter she received that contained racist comments, saying she can’t ignore it and wants white people to fight against it.

The answer was no. Sherman said many of his teammates were sympathetic to the cause, but feared how they would be perceived outside the locker room.

“There were conversations had behind closed doors where it was like, ‘Hey, I want to stand with you guys. I want to make the point. I want to protest. I want to do my part. But if I sit, I kneel, I do anything, then I won’t be able to go home to my family. Because my family sees this a certain way,’” Sherman said.

The difference this time, he said, is that “players are doing everything in their power to use their platforms or their social media, whether it’s press conferences, using their own money, their foundations to reach out and do the actual work.”

The panel discussion then turned to person experiences of racism. Sherman, who now plays for the San Francisco 49ers, grew up in Compton, where he learned a set of rules that might be unfamiliar to much of White America.

“We learn how to deal with police, how to deal with authority figures, how to not look intimidating, how to not be the angry Black man, how to be calm,” said Sherman, a five-time All-Pro selection. “Because those are things you need to be able to maneuver in this world as a Black man. If I’m a white suburban kid, I don’t have to learn how to deal with cops and keep my hands on the steering wheel, no quick movements, sometimes put your hands out the window to make sure that you’re not threatening. If anybody runs up on you, try to not seem confrontational. Your parents teach you those things.

“Even in college,” said Sherman, who attended Stanford, “you have people walking by you grabbing their purse. Because if they don’t know who you are, if you’re not wearing athletic gear, then you’re just an intimidating Black man to them. Angry Black man.

“Every time you go out anywhere, you drive and the police pull up behind you, you know it’s bad. In L.A., as soon as they get behind you, you know, `I’m getting pulled over. My day is going to be ruined today.’ So it’s hard for me to fully explain the frustration. But I think people are trying to express it and finding different ways to express it, whether it’s protesting, rioting, burning down buildings, etc. Not to say it’s the right way, but that’s how people are expressing their anger, because it hasn’t changed.”

Dungy recalled his family struggling to steady itself in the aftermath of King’s assassination. He remembers “my dad taking us and sitting us down and saying, ‘Here’s what the world is like. And there are people who are going to dislike you for no reason, just because of what you look like. There are going to be people who think differently. But in this house, this is how we’re going to treat people. We’re going to treat people with the love of Christ. We’re going to treat people with respect. Doesn’t matter how they treat you, that’s what we’re going to do in our house.’ To me, that’s what’s got to happen in this.

“Everybody around the country who sees this and are upset, they’ve got to start at home and say, ‘First of all, I may have to make a change in how I do things. But at least with people in my home and my sphere of influence, I’m going to make a difference. Then when I go to work or I’m in my neighborhood, I’m going to have the boldness to make a difference.’ That’s how we’ve got to start it. It’s got to be changing hearts one by one. That’s the way it’s going to be long lasting.”

Whereas Woods said he expects more kneeling this season, Sherman anticipates players being more strident in interviews.

“I expect a lot more of them to convey these messages, to convey messages about police brutality, equality, the systematic racism that’s been going on,” Sherman said. “And to have statistics. Because we have really intelligent and sharp players in our league who get the information and convey it. That’s the part where fans are going to have to work with us a little bit.

“With football, you want to forget about politics. You want to forget about all the stuff you have going on. But right now you can’t. When you haven’t seen a Black person your whole life, you don’t interact with them on a daily basis, but your favorite player is a Black player, there should be some kind of relationship and empathy there, but there isn’t.

“Us using that platform to make the point might turn some fans off, but it is what it is. Guys are going to continue to fight the good fight.”

Dungy said he’s looking for more than a symbolic act during the pregame ceremonies.

“I don’t think it can be just the kneeling,” he said. “… it’s really taking advantage of those press conferences, getting your voices out there and saying, `This is what I see. This is what’s going on in my community. This is what needs to happen as a solution.’ Then that young fan who maybe doesn’t know you but you’re his favorite player, he says, `Man, Richard Sherman is concerned about this. Maybe I should be impacted by it.’”

On one issue, Sherman and Dungy didn’t agree: Whether Kaepernick will get a chance to resume his NFL career.

Tyrod Taylor is the Chargers’ starting quarterback and he has two backups, but coach Anthony Lynn said Colin Kaepernick fits the team’s scheme.

“People make a big hubbub about he hasn’t thrown a pass in however many days, but there are tons of backup quarterbacks in this league who haven’t thrown a pass in a live game outside of the preseason in a really long time,” Sherman said. “So I don’t think that will matter. It’s like riding a bike. He’ll get out there, he’ll get a feel, he’ll maneuver, and he’ll play as he always played. But I don’t think teams are willing to do it, as they haven’t been… If teams were willing to do it, they would have done it years ago.”

Countered Dungy: “I think a lot of people in the league respond to political correctness. Three years ago, it wasn’t politically correct. Now, maybe it is, or it’s seen in a different light. I hope he gets a job, and I think he might because of the climate change.”

::

The full transcript of the panel’s discussion can be found here: http://netblogpro.com/sports/story/2020-06-19/richard-sherman-duny-woods-racism-black-lives-matter-nfl

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.