1968: Medals stand protest became model for sports activism; it just took a while

That autumn night at Estadio Olimpico Universitario might not have been so memorable if Tommie Smith and John Carlos had merely each raised a black-gloved fist into the air.

The mournful way in which the U.S. track stars bowed their heads, the vulnerable manner in which they stood shoeless, made the gesture something beyond menacing.

“We are black and we are proud of being black,” Smith said. “Black America will understand what we did tonight.”

The photograph of their protest on the medals stand at the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City ranks among the most unforgettable images in the history of sport.

The sprinters hoped to draw attention to the treatment of blacks in an America still struggling with integration. By removing their shoes, they sought to empathize with the poor.

The power of the moment triggered a worldwide response — some praised Smith and Carlos as heroes, others dismissed them as “militants” performing a “Nazi-like salute.”

Regardless, it was expected that their actions would spark a wave of social consciousness among athletes. Carlos predicted as much, saying that competitors at the next Summer Olympics might “tear the place down.”

But a crusade never materialized, with sports protests few and far between in the years that followed.

“In a way, we were still trying to figure out what it means for an athlete to be a public figure,” historian Kevin Witherspoon said. “The conversation has played out for decades.”

Half a century later, a new generation of sports activists has finally emerged, led by players such as quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who started a trend by kneeling during the national anthem before NFL games.

Why did it take so long for athletes to follow the lead of Smith and Carlos?

The answer lies in the backstory to that evening in 1968.

When Pierre de Coubertin launched the modern Olympics in the late 1890s, he made a point of holding them in conjunction with the World’s Fair. The Frenchman wanted international exposure, hoping his competition would encourage goodwill and sportsmanship.

But Adolf Hitler had other purposes when he commandeered the stage in 1936, using the Berlin Games to promote Nazi Germany.

“The genie was out of the bottle,” said Mark Dyreson, a Penn State professor who has written extensively about the Olympic movement.

So-called state actors had discovered they could use the Games to their advantage. It took a while for non-state actors — the athletes — to catch on.

The idea came to Harry Edwards, a former discus thrower teaching sociology at San Jose State, around 1967. By then, television had transformed the Games into a global spectacle while rendering the World’s Fair less relevant. Edwards spotted an opportunity.

Eager to address racial tensions in the United States, he persuaded a group of athletes to join his Olympic Project for Human Rights, which called for the hiring of more black coaches and the ouster of International Olympic Committee President Avery Brundage, whom many people viewed as racist and anti-Semitic.

Early in 1968, the OPHR orchestrated the boycott of a New York track meet. A similar effort directed at the Summer Games lost steam, with only a few basketball players — including Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, then known as Lew Alcindor — choosing to skip Mexico City.

Edwards hatched another plan in talks with top American runners such as Carlos, Smith and Lee Evans, who were taking his classes at San Jose State.

“We could not get to the podium of the United Nations,” Edwards said. “The point was to get some people on the Olympic podium so that they could make a statement to the world that we have a human rights problem in the United States.”

By the fall of 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Police had clashed violently with protesters outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

As the Summer Olympics drew near, Mexican troops opened fire on thousands of pro-democracy demonstrators in that nation’s capital.

“That year is such a flash point,” said Witherspoon, an associate history professor at Lander University in South Carolina. “The American athletes are young men, they’re college students, and they are observing all this.”

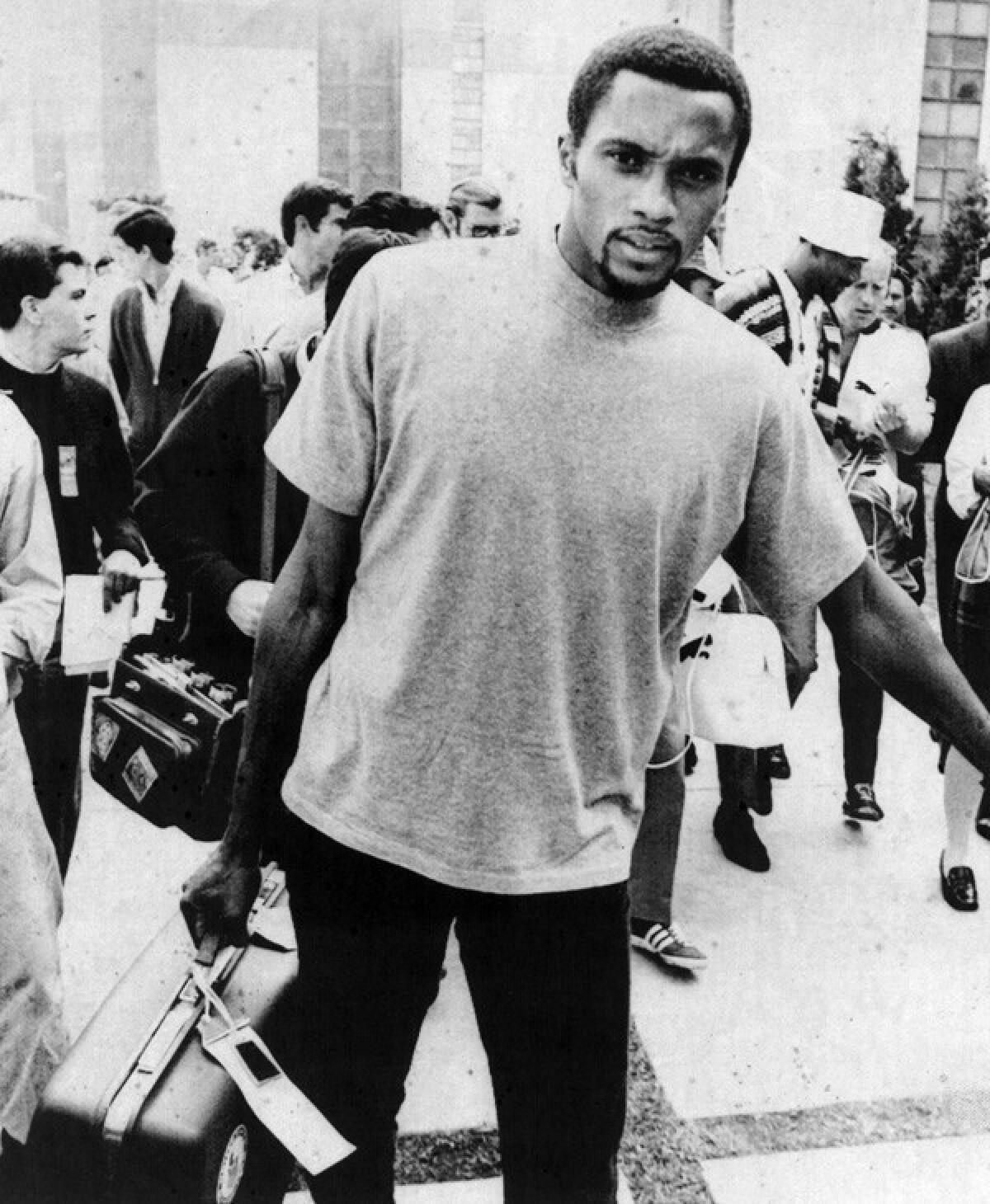

Whispers of an impending protest circulated around the Games leading up to Oct. 16, the day Smith won the 200 meters in world-record time, with Carlos finishing third.

The teammates would later disagree about what happened next. In a 2001 interview with the Los Angeles Times, Smith said they grew reluctant to speak to the media for fear of opening old wounds.

“I was much more frightened on that stand than I had ever been on the starting block,” he said. “But I felt I had no choice. … I had to show the world what life was like off that stand.”

Neither he nor Carlos responded to interview requests for this article, but there was a third man on the podium, the late Peter Norman, an Australian whose experience that day has been detailed in a book and documentary film.

Because his country was enmeshed in Aboriginal protests, Norman knew about the U.S. civil rights movement. He recalled that on Oct. 16, Smith and Carlos had only one pair of black gloves between them.

“Peter was the one who suggested they wear one each,” said Matt Norman, a nephew who produced the book and film about his uncle.

As the three medalists chatted after the race, Carlos borrowed an OPHR button from another American athlete and handed it to Norman, who pinned it to his uniform.

“My uncle knew it was a dangerous thing to do,” Matt Norman said. “But he believed it was important to stand beside them.”

Once the medal ceremony began and the anthem played, Smith and Carlos kept their heads bowed to avoid acknowledging what they saw as an oppressive society. Their raised fists mimicked a popular black power salute and they stood without shoes to recognize poverty in America.

In doing so, they had violated Rule 50.2 of the Olympic Charter: “No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas.”

Boos rained down from the crowd and the pair was subsequently banished from the athletes village. Back home, they were shunned by much of the track-and-field establishment, effectively ending their athletic careers. Norman paid a similar price.

Australia left him off the team for the 1972 Games in Munich, Germany, even though he had qualified and still holds the national record for 200 meters.

When Norman died in 2006, Smith and Carlos served as pallbearers at his funeral.

“He always said that if he could do it again, he would do it exactly the same,” said Matt Norman, who has negotiated a deal for a Hollywood film about his uncle. “His race lasted 20 seconds. … His stance has lasted 50 years.”

Smith and Carlos’ actions overshadowed much of what happened in Mexico City that fall.

World records fell, one after another, and Bob Beamon flew more than 29 feet to set a long-jump standard that survived until 1991. People might forget that other Americans, including Evans and members of the victorious 1,600-meter relay team, also raised their fists.

Despite Carlos’ prediction, only a few U.S. athletes protested in Munich four years later; sprinters Wayne Collett and Vince Matthews refused to stand at attention during the anthem.

“I love America,” Collett told The Times before his death in 2010. “I just don’t think it’s lived up to its promise.”

When discussing the scarcity of activism among Olympians in the years that followed 1968, historians suggest the consequences might have been too severe for runners, swimmers, gymnasts and others who do not have major-league contracts waiting for them after the Games.

“The question for athletes has been: ‘What are you willing to do?’” Dyreson said. “I think it’s been hard for them to be courageous. It’s about risking their post-Olympic career.”

Edwards sees things differently. The sociologist and social activist has identified historical “waves” of athlete protests that he believes are linked to — if not instigated by — broader social conditions.

The first wave arose from segregation in the United States throughout much of the 20th century, as the likes of Jesse Owens, Jack Johnson and Joe Louis struggled for inclusion.

After World War II, a new generation, including Jackie Robinson and Earl Lloyd, sought to break the barriers that kept blacks out of team sports.

“History never repeats itself,” Edwards said. “But the dynamics of history remain the same.”

The third wave of activism in the late 1960s — highlighted by not only Smith and Carlos, but also by Muhammad Ali — was triggered by the civil rights, anti-war and black power movements. Athletes now struggled for dignity, respect and self-determination.

Smith and Carlos suffered for their actions, as did Ali, who sacrificed the prime of his boxing career to protest the Vietnam War. Yet Edwards disagrees with historians who see them as a cautionary tale.

Protest in sports dropped off, he believes, for reasons other than money and fame.

“The collapse of the civil rights movement, the demise of black power,” Edwards said. “There was no ideological movement framing the activities of athletes.”

It was the early 1990s when Charles Barkley filmed a much-debated commercial for Nike.

“I am not a role model,” he said, staring directly into the camera. “I am paid to wreak havoc on the basketball court.”

Though Barkley was making a larger point — that parents should take responsibility for raising their children — his words came to exemplify an era when superstar athletes, including Michael Jordan, rarely spoke out on social or political issues.

“There were minor protests along the way,” Witherspoon said. “Nobody replicated what happened on the medals stand.”

But attitudes have shifted in the last few years. Some NFL players began kneeling during the anthem. In basketball, Stephen Curry criticized the political stance of a shoe company that had endorsed him, and Carmelo Anthony issued a challenge.

“I’m calling for all my fellow athletes to step up and take charge,” he wrote on social media. “There’s no more sitting back and being afraid of tackling and addressing political issues anymore.”

This fourth wave of sports activism makes sense in Edwards’ paradigm, arising alongside the Black Lives Matter movement, fostered by a partisan divide over President Trump’s policies.

Once again athletes seem eager to get involved, even if it means risking their livelihoods.

It feels “a bit like the old times,” Carlos recently told “The Undefeated” website. Edwards voiced a similar reaction.

“There’s a direct connection to what happened in the 1960s,” the professor said. “When you look back, you have a blueprint for the utilization of the sports platform to protest.”

Edwards added: “At a certain point, the cost becomes irrelevant because the cause is so critical. Injustice pushes the envelope to the point where that protest reaction becomes inevitable.”

Amnesty International and the ACLU recently honored Kaepernick for his activism. He has arguably endured a plight similar to that of Smith and Carlos.

No team has signed him since he opted out of his contract with the San Francisco 49ers after the 2016 season. He has filed a grievance against the NFL, alleging that team owners have colluded against him.

Which might explain why he placed such importance on meeting Smith and Carlos last year. In a social media post, Kaepernick referenced their “connected struggles” and the lasting power of that moment in 1968.

“Hearing them tell their stories, sharing behind the scenes insights into the sacrifices they willingly made, and the ostracization that was forced upon them,” he wrote, “all that I could do was listen, take notes, and soak in the elders’ wisdom.”

Twitter: @LAtimesWharton

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.