Column: NFL draft is virtually flawless, but serves as reminder of our changed world

An improbable dream was about to transform into reality. Years of hard work were about to be rewarded.

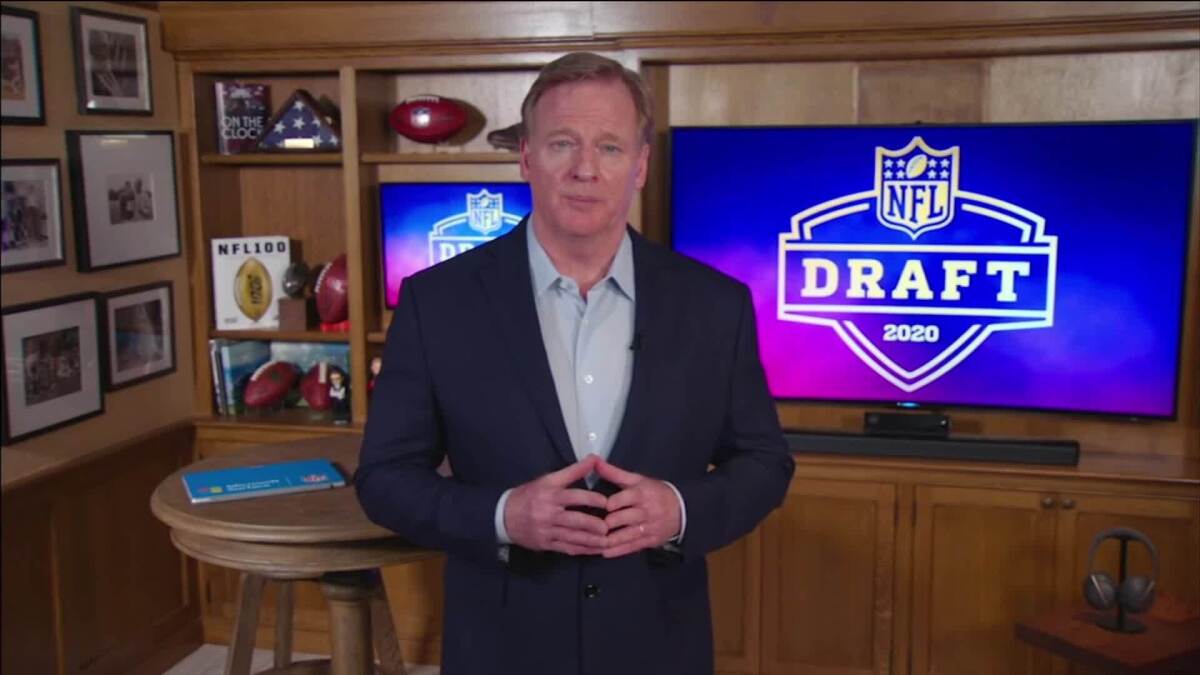

“OK, here we go. …,” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell started, holding a navy-blue card adorned with the league’s insignia.

“With the first pick of the 2020 draft,” Goodell continued, “the Cincinnati Bengals select Joe Burrow, quarterback, LSU.”

The broadcast moved from the basement in Goodell’s residence to the living room of the Burrow family home in Ohio. On a sofa sandwiched by his parents, Burrow wore white headphones as he stared down at his mobile phone. His father placed a hand on his back. His mother did the same.

This was a transformative moment for the Bengals and the city of Cincinnati, for Burrow and his family … and something was missing.

There was no crowd.

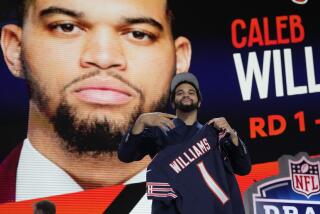

The NFL draft’s first round provided some surprises as NFL went contact-free because of the coronavirus.

As much as Goodell and the broadcasters warned viewers of the multi-channel telecast that this draft would be unlike any before it, as much as social distancing has become the norm, the absence of a live audience was striking.

The public thirst for sports-related programming was overwhelming, the coordination and technological wherewithal required to stage a virtual draft was remarkable, but none of that could replace the block party that was supposed to take place on Las Vegas Boulevard.

While the first round of the draft was a welcome diversion, the Thursday broadcast was also a 31/2-hour reminder of the problems sports leagues should consider as they make plans to restart play in empty venues.

Sports leagues and teams have often taken their fans for granted. Many have prioritized their profit margins to where the well-being of their loyal patrons is an afterthought, raising ticket prices and locking themselves into television deals that inconvenience viewers. Their implied message is that fans are privileged to consume their product.

The product, however, feels less important when there are no fans. That was the case with this draft, which disproved long-standing assumptions. The star of these shows wasn’t Goodell or any of the players. All these years, the stars were the adults in war paint wearing officially licensed jerseys of their favorite teams bearing the name of people they have never met.

The NFL Network, ESPN and ABC offered live looks into the homes of players, coaches and executives, which was promising. Some memorable images were produced, among them Las Vegas Raiders pick Henry Ruggs III wearing a robe and Arizona Cardinals coach Kliff Kingsbury stretched out in his desert bachelor mansion. A number of players were noticeably moved when selected. Nonetheless, the proceedings were short on emotion compared with previous years.

There’s something special about witnessing the moment a family’s financial realities forever change. Evidently, it’s even more special when that moment is shared with tens of thousands of others, even if they’re strangers.

In terms of informing its viewers, the broadcast had advantages. Goodell’s voice didn’t echo over a public- address system. But here, too, an intangible something was lost.

This isn’t to say the NFL erred by staging the draft. As mentioned above, this was a welcome distraction.

But what the NFL, the NBA and Major League Baseball have to be mindful of when planning to resume or start their seasons is that what works for a draft won’t necessarily work over several months’ worth of games. A draft is a one-time event. In that instance, a watered-down product is acceptable. And, surely, when games return, fans will initially watch. The question is whether they will continue doing so when it becomes clear the product is diminished by the monastery-like atmosphere of empty stadiums and arenas. The guess here is that many won’t.

Consider how many fans who make proclamations about how much they prefer playoff baseball to regular-season baseball. What’s the difference between the two?

The intensity in the stands.

The Chargers kept the No. 6 pick and selected Oregon quarterback Justin Herbert. They then traded to get the 23rd pick and took Oklahoma linebacker Kenneth Murray Jr. in the NFL draft.

Of course, that won’t stop the games from being played. There is money to be made. ESPN’s pre-draft countdown made it a point to mention the corporate partners providing the means of communication.

Goodell’s awkwardness ruined an otherwise clever idea to transform fans’ disdain of him into a beer advertisement.

Similarly, leagues will be looking to play enough games to satisfy the demands of their television contracts and ensure that revenue stream continues to flow.

But the games will be different. And unlike a one-night draft, people will have the time to process how different the games feel and come to understand why.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.