Wilder-Fury 2 could help boxing’s heavyweight division up off the canvas

LAS VEGAS — It’s been the flagship of boxing. Been on the fringe too. Forgotten even. From Atlantic City to Zaire, eras and ears have come and gone in the heavyweight division, all defined by distinct names, faces, voices and scars.

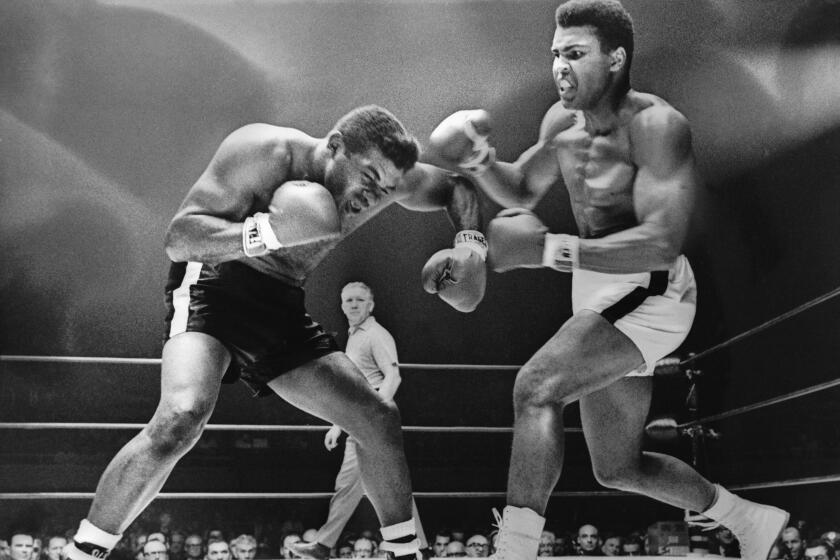

There was Jack Johnson. There was Jack Dempsey. Then, Joe Louis. Then, Muhammad Ali. Then, Mike Tyson. All had an impact, each leaving echoes still heard like the rhythm from a distant speed bag in a busy gym.

The beat goes on.

A sure sign of what has become of the heavyweights — and perhaps where they are headed — is on the horizon. The Tyson Fury-Deontay Wilder rematch Saturday at the MGM Grand could be a significant milestone. Has the division evolved? Or it is still stuck in the stagnant ditch it occupied just a few years ago?

Fair or not, nobody paid attention to Wladimir Klitschko, who Fury beat in 2015 after telling the stoic Ukrainian that he “had about as much charisma as my underpants.”

Don’t misinterpret top boxing matches being held in many other cities as a sign of the sport abandoning Las Vegas. Sin City remains the world’s fight capital.

For a time, Klitschko fought names nobody knew. He won. And won. He was a reliable role model, but heavyweight history has always played out on the big stage. It’s remembered for Johnson’s defiance and Ali’s mouth and Tyson’s wild ride. Take the drama out of the division and you’re left with a fossil.

Now, however, there is noise about a heavyweight revival. At least the elements for one appear to be in place.

In Wilder, there is singular power in one punch that is generating historical comparisons to George Foreman, Sonny Liston, Earnie Shavers and Tyson. In Fury, there is showmanship, wit and a compelling back story. From both, there has already been drama.

About fourteen months ago, they fought at Staples Center preceded by little anticipation. But it ended in a thunderclap, with Fury getting up twice — first in the ninth round and again in the 12th — from the right-handed power that Wilder has used to knock out 41 of 43 opponents.

In the books, it was noted as a split draw. There was controversy about the scorecards — one for Wilder, one for Fury and one even. But there was no split in what it created. The demand for a sequel was unanimous.

“Me and Wilder, this has to be the biggest heavyweight fight since the 1970s,” Fury told reporters Tuesday after arriving at the MGM Grand. “Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier, 1971, about 50 years ago. It took awhile to get another massive heavyweight fight.”

Fury is an Irish Traveler, the son of people who crisscrossed Britain as a traveling show, with circus acts and bare-knuckled brawls. The big top is in his genes. He has performed on the pro-wrestling stage and brought some of those over-the-top acts into prizefighting. The shtick isn’t new. Think Ali, who studied and borrowed from Gorgeous George, one of the most flamboyant pro wrestlers in the early 1960s.

Expect a lot of mocking, talking and punchlines from Fury. Expect some of the same from Wilder, who walks into the ring in costumes that look as if they could have been worn by a Mardi Gras reveler parading up-and-down Bourbon Street.

But how will the action after opening bell stack up against the great heavyweight moments? Fury mentioned 20 years because there’s a consensus among experts that Wilder-Fury 2 is the biggest heavyweight match since Lennox Lewis scored an eighth-round stoppage of Tyson on June 8, 2002 in Memphis. Depending on the perspective, that was either the end of a good heavyweight era or the beginning of a forgettable one.

The long wait for the next great heavyweight also has created the inevitable search for historical parallels. As heavyweight champions, the 6-foot-7 Wilder and 6-9 Fury are bigger. They are NBA big. But are they better?

“Listen man, if I was here now, in my prime now, I’d say good night to all them guys,” said Larry Holmes, an Ali sparring partner who won the title from an aging, ailing Ali in 1980 and defended it 12 times with a versatile skill set that included a long, lethal jab punctuated by a solid right hand.

Holmes, who is often left out of the best-heavyweight argument despite his long reign, says Wilder and Fury probably would have been ranked near the bottom of the top 10 in his day.

“It’s not for me to put them down,” Holmes said. “But you got Ken Norton. You got Muhammad Ali. You got Joe Frazier. You got Ron Lyle. You got so many guys. Not only could they box, they could punch. Can these guys take punches? Can they take 10 or 15 punches for 15 rounds, 12 rounds, 10 rounds or whatever? Now guys get hit, guess what happens? It’s all over.”

Tyson Fury keeps his demons at bay while readying for a rematch with fellow unbeaten boxer Deontay Wilder, who battled him to a draw in their first bout.

Yet, Holmes, like fans and fellow fighters, is interested. He picks Wilder to win. But he can also envision a Fury victory. It’s a pick-em fight.

“I’m not going to put them in a class above their ability,” Holmes said. “I put them in a class at where they’re at, because they’re all in the same class.”

There is never a winner in the kitchen-table argument comparing eras. The World War II father remembers Louis. His son remembers Ali. Louis versus Ali is little bit like today’s debate about Michael Jordan versus LeBron James.

“I don’t know how you can compare,” said Larry Merchant, HBO’s retired ringside commentator who was a newspaper columnist during Ali‘s reign. “I mean, look, there were big guys in the old days. There was Primo Carnera, Abe Simon, Max Baer. But, like a lot of big guys in any sport at that time, they were sort of stationary, not as mobile as big guys are today.”

In part, interest in Wilder and Fury is rooted is how two of the biggest heavyweights in history have evolved.

“Fury is as big as an ox and moves like a ballerina,” said former heavyweight champion Foreman, a feared puncher remembered for ferocious, two-fisted power that sent Frazier bouncing off the canvas in a second-round stoppage Jan. 22, 1973 in Kingston, Jamaica.

Foreman is also remembered for losing to Ali in what was then Zaire in an October 30, 1974 bout known as “The Rumble in the Jungle.” Foreman lost to the better boxer on a night when Ali practiced what he called “The Rope-a-Dope.” Ali endured Foreman’s concussive blows for five, six rounds. By the seventh, Foreman began to tire. In the eighth, he was exhausted. That’s when Ali capitalized, landing a succession of punches, including a left hook and right that finished Foreman. The boxer beat the puncher, and that’s what Foreman thinks will happen here Saturday. He picks Fury to win a decision.

“Tyson Fury moves around, throws his head, tries to trick you,” Foreman said. “Everything a small guy does, Fury does. He uses his feet the way smaller guys do. He uses that style and stays out of harm’s way. He beats you. He would have lasted in any era.”

Fury has skill learned from his family’s Traveler tradition. He’s been boxing since he was a kid. In interviews with the British media, his father, John Fury, remembers a day when Tyson, then 14, playfully sparred with his dad. The teenage son broke one of his father’s ribs.

Evander Holyfield, who picks Wilder to win, says Fury’s instinctive style represents a significant advantage over Wilder, who was late to boxing. First, Wilder wanted to play football at Alabama. He’s a lifelong resident of Tuscaloosa. Then, he wanted to play basketball. Finally, he wandered into the gym and discovered a right hand that has carried him to the top of the heavyweight division. He’s been called one-dimensional, and one dimension might not be enough to beat Fury.

“Part of being a great fighter is knowing who you are,” said Holyfield, whose heavyweight reign in the mid-to-late 1990s is best remembered for beating Tyson twice — and losing part of an ear in the second bout, the infamous “Bite Fight” here on June 28, 1997. “Deontay understands that. He knows, ‘I might not have more of what everybody else has. But what I do, I do real well. I’ll do that.’ And he wins.

“As a fighter, you got to do what works for you.”

At the Boys & Girls Club in Nickerson Gardens, organizers hope boxing classes can help children avoid falling into a cycle of violence and hopelessness.

Holyfield says the current generation of American heavyweights has suffered from the lack of an amateur system that was in place when he was young. Boxing became a pay-for-view event, which Holyfield says eliminated the poor kids who become good fighters. They couldn’t afford to watch, which robbed them of the Ali-like hero that Holyfield, Riddick Bowe, Lewis and Tyson had as kids.

“We all wanted to be like Ali and we all became champions,” Holyfield said. “But if kids can’t afford to see it, they’ll do something else. They’ll go into MMA or something. They do what they see. They do what’s popular.”

Fury-Wilder 2 is also a pay-per-view bout, a joint ESPN-Fox venture. The price tag: $79.99. That rival networks are cooperating on one fight is a sure sign that a big audience is expected. Top Rank’s Bob Arum, who is known to exaggerate, has predicted 2 million buys. More than 1 million is probably a success. Interest is evident from so-called casual fans and celebrity fans.

Charles Barkley, a former NBA great who is an analyst on TNT’s “Inside the NBA,” is keenly interested. He’s a longtime fight fan.

“I love it,” Barkley said. “I admire their courage.”

Yet, Barkley has frustrations shared by many fans. He grew up in the Ali era, which became golden in large part because all the contenders fought each other. Ali lost to Frazier and then to Ken Norton, yet he overcame the adversity, a measure of how great he really was.

“You can’t compare eras, because these guys don’t fight each other enough, not like the way they did during Ali’s time,” Barkley said. “That’s not just true of the heavyweights. It’s true for the rest of boxing. Too many guys want to be undefeated. They want to walk around, saying ‘I’m undefeated.’ OK, but who have you fought?”

Athletes have been turning to other sports for years, since Ali, who might have been a tight end or shooting guard if he had been born later. The long-term damage from head blows in boxing is no secret. Boxers have been willing to assume the risk for years. Barkley said the same thing is now happening in football because of concussions.

“Football and boxing are two of my favorite sports,” Barkley said. “But man, they are really dangerous.”

Barkley never tried boxing while growing up in Alabama, where Louis, Holyfield and Wilder were born. From high school to Auburn to the Philadelphia 76ers, Phoenix Suns and Houston Rockets, he was always a basketball player. If he’d been born at about the same time as Ali, would he have been a power puncher instead of a power forward, a boxer instead of a Basketball Hall of Famer?

“Boxing is awesome to watch,” he said. “The notion that somebody can punch you in the face and you can’t do anything about it is amazing to me.

“But in answer to your question: Hell no.”

But he’ll watch Fury-Wilder 2. One fighter got up off the floor in the first one. Maybe, an entire division will get up in the rematch.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.