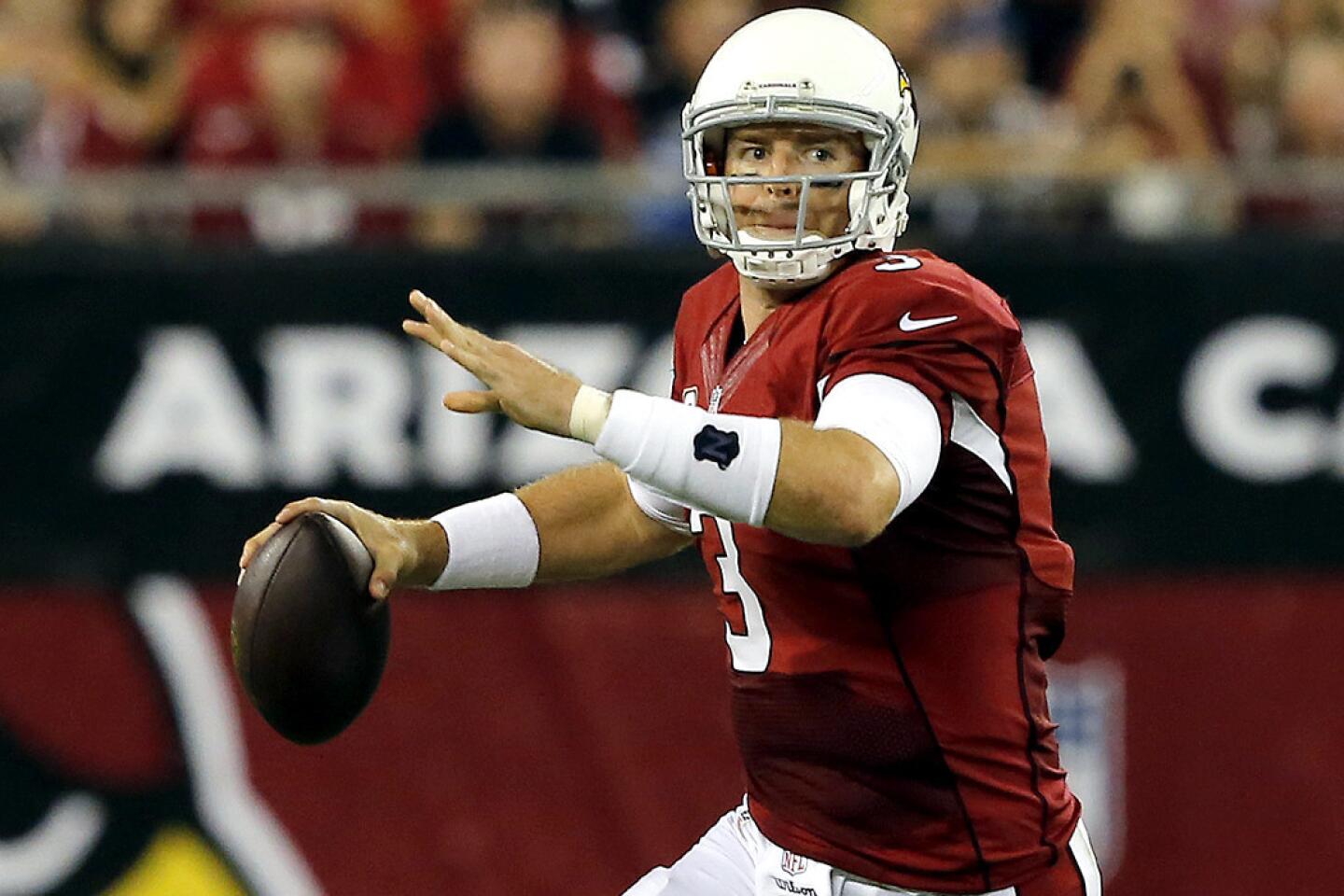

KETCHUM, Idaho — Just as he did as a Heisman Trophy-winning quarterback at USC, as a No. 1 overall pick in the NFL draft, and in 15 years as a pro, Carson Palmer still keeps his throwing arm in shape. He does light lifting to strengthen his shoulder joint and maintain his flexibility, all to prepare for the season.

Snowball season.

“If I miss you, I’m trying to miss,” said Palmer, 40, who threw 299 touchdown passes in his career with the Cincinnati Bengals, Oakland Raiders and Arizona Cardinals. “I’m deadly with a snowball.”

After Palmer retired at the end of the 2017 season, he and his wife, Shaelyn, moved their four children to this picturesque resort town of 2,800 people, where being a fan of the three major sports means you like to hunt, fish and ski.

To the bewilderment of many of his old teammates, Mr. Throw’em is now Mr. Ketchum.

“I have buddies who say, ‘Where are you living ? Wyoming or something? Don’t you still have a house in California?’ ” said Palmer, sitting on the kitchen counter of the family’s sprawling home on four snow-covered acres. “I tell them we live in Idaho, and you can see it on their face and sense it in their voice: ‘Um ... O ... K.’ ”

Palmer turned down a job to be a color analyst on Fox and has decided not to pursue coaching opportunities, even though football is stitched like laces through his DNA. He is intensely private, especially when it comes to his family, so when he walked off the gridiron, he was determined to step off the grid.

That means fly fishing for rainbow trout in the morning and skiing Sun Valley in the afternoon. It means helping get his kids ready for school — twins Fletch and Elle, 10; daughter Bries, 8; and son Carter, 3 — then tag-teaming with Shaelyn to shuttle them to ski team, ice skating and guitar lessons. Palmer happily has gone from one of the most celebrated and glamorous jobs around, one of 32 starting quarterbacks in a league watched by tens of millions, to the routine of a quieter life.

“This is who Carson is and has always been,” Shaelyn said. “He never wanted to be famous. He always turned away from anything having to do with that. For those who know Carson, this is his most natural environment. Being outside. Just being a normal guy. Being a dad.”

Born in Fresno and raised in Orange County, Palmer fell in love with Ketchum and the outdoors during his teens, when he regularly made summer trips to Idaho with family friends. He and his close pal, Jake Rohe, would spend their days working out on the playground at nearby Hemingway Elementary, only stopping when one of them would get sick. When they weren’t exercising to the brink of collapse, they were fishing.

“I fell in love with having my feet in the water and a fly rod in my hands,” Palmer said.

That’s a common sentiment in this community, where locals are accustomed to living among celebrities. Tom Hanks, Clint Eastwood, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Robin Williams all had homes in the area at one point or another. Bruce Willis and Demi Moore once called Ketchum home. Just down the road from the Palmers is the grave of Ernest Hemingway, who spent his final years in Ketchum.

Before buying a place of their own, the Palmers rented from golfer Davis Love III, who has a home directly across the street from a ski lift. That house became available when Love took a spill on the slopes and broke a collarbone.

“This community treats celebrities just like they treat everyone else,” said Guy Robbins, who has multiple jobs in town, among them a fishing guide for Silver Creek Outfitters. “It’s not, ‘Oh my god, can I get a selfie?’ That doesn’t happen in this town with the people who live here.”

That’s not always the case. The 6-foot-5 Palmer can’t always blend into the background. Recently, while he and Robbins were at a remote fishing spot an hour outside town, they happened upon a fellow traveler in a Pittsburgh Steelers jersey.

“Take off your glasses,” the man asked of Palmer, barely able to utter the words.

Palmer complied, to which the stranger said: “I knew it was you!”

With his wife out of town recently, a rare occurrence, Palmer handled solo parenting duties and finished the day by taking his children to dinner at the Pioneer Saloon, a Ketchum institution. Twenty minutes into the meal, a man at the next table did a triple-take, went away for a few minutes and reappeared with a bottle of wine as a gift for Palmer. It turned out the man was a fellow USC graduate, ecstatic to be sharing the same restaurant as the quarterback who launched the Pete Carroll era.

“I’ve got a signed football from you,” the flabbergasted fan said.

“Good job,” chirped preschooler Carter, drawing laughs from both tables.

Palmer has a satellite dish at home and watches about 75% of the games involving the Cardinals and USC. He keeps up on what’s happening in the NFL because he still does a handful of weekly interviews for radio and podcasts and does brand representation for Kadenwood properties and FedEx. He’s looking into property-development opportunities in Ketchum and is considering a role in local government; he has been appointed to a seat for the Ketchum Urban Renewal Agency.

The Palmers have yet to decide how long they might stay in Ketchum. They love the town and the one school all their children attend. Both parents grew up playing ball sports — Shaelyn was a soccer player at USC — but those are an afterthought when it comes to youth sports here.

Fletch, a fifth-grader, wants to play quarterback, but his parents won’t let him start playing tackle football until eighth grade and the community doesn’t offer a flag-football alternative. The family still owns a farm in Ohio and a home in Del Mar.

“We wanted to raise our kids away from the hustle,” Shaelyn said. “We also didn’t want them having pressures because of Carson’s career. Especially Fletch. He was getting that really hard-core in Arizona. Everyone thought he was going to be the best quarterback. You just want them to be who they are. This took the pressure off him.”

Carson and Shaelyn point to their own parents as role models who spent as much time with them as they could. But Palmer said he missed “a ton of stuff, almost everything” when he was traveling and consumed by game preparation as an NFL quarterback. That wasn’t just when he was traveling but also while he was studying video, meeting with teammates and getting physical therapy.

“It’s an all-consuming job,” he said.

To the Palmers now, that feels like a lifetime ago.

“He’s had a million opportunities since he retired,” Shaelyn said. “Job offers, travel. There’s a lot of guys who would say, ‘Awesome. I’m going to go travel three days a week and make X amount of money.’ But he chose our family.”

Some things haven’t changed: For several years, Palmer has agonized watching USC’s football team struggle on the field.

“It’s hard to engage when you’re very prideful about something,” he said. “It’s frustrating, like anybody with their alma mater, when you just disagree with some of the things that are going on. You know how good it can be, and how easy — not that it’s easy — but, man, we should be a top-five recruiting class every year. How are we not?”

Palmer won the Heisman as a Trojan in 2002, but the trophy is not in his possession. He used to keep it in his garage but recently honored the request of sports media personality Dan Patrick and loaned it to him to adorn a studio in Connecticut.

“I have a lot of interesting things in my man cave,” Patrick said. “But the Heisman shows up, and the base of it is beat up. It looks like it’s played in a game, like the Bengals’ offensive line has pass protected for it.”

That Palmer would part ways, if only temporarily, with such a revered piece of sports hardware is not particularly surprising to Patrick.

“I always thought there was something a little more unique with him,” Patrick said. “I go back to his days with the Bengals, and when he decided that he’d rather not play football than play for the Bengals. I think he was understanding of the joy in life, or how do I get that satisfaction?”

A pivotal moment in Palmer’s career came during a playoff game against Pittsburgh at the end of 2005 season, when he suffered a gruesome knee injury on his opening pass.

“Sometimes there’s that first real shock of, this could end tomorrow,” Patrick said. “I think he always had perspective on that. What is quality of life? ‘I won the trophy. Why not let others see it and share it with them to give them some kind of joy?’ ”

Roughly 2,500 miles to the west, Palmer is enjoying a different kind of reward: time with his family.

“Playing quarterback is a glamorous job. It’s awesome. It’s everything I dreamed it would be,” Palmer said. “But after a while, it loses its glamour. Somewhere along those 15 years, it becomes a job. Especially at the end, it became work. Game day was awesome, but all the rest of it was work.”

So would he trade the life he has now for more NFL glory?

Snowball’s chance.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.