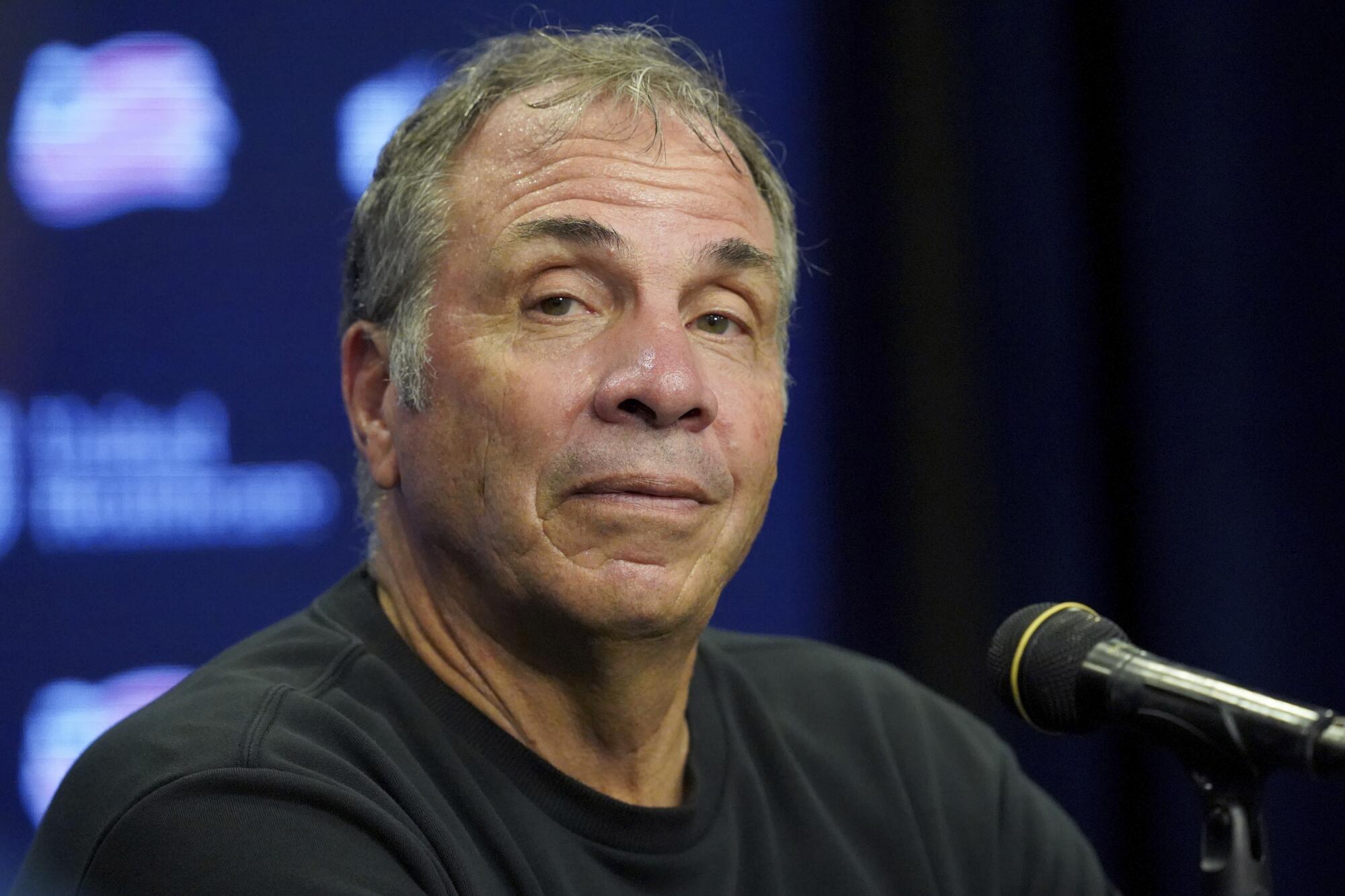

FOXBOROUGH, Mass. — On most days, Bruce Arena is among the first to arrive at the New England Revolution’s training center, a 68-acre complex carved out of densely wooded wetlands 30 miles south of Boston.

At 70, Arena is at both the apex and the end of his career. The most successful American soccer coach of all time, he has never had a team perform at a higher level than this season. After turning around more organizations than Lee Iacocca, Arena came out of retirement 2½ years ago to take over a floundering franchise that hadn’t had a winning season in four years and guided it this year to the best regular-season record in MLS history.

When Arena is in the mood, the still early-morning hours — when he has only the soaring pine, birch and oak trees outside his office window for company — offer a chance to reflect on how he got here. The answer, he said, continues to elude him.

“I don’t even know why I took the job, to be honest,” he said on a recent quiet morning. “I did [it] with some reluctance because I wasn’t sure it was the right thing to do.”

There can be no doubt now since this season has provided the only appropriate coda to an unparalleled list of achievements that includes four consecutive NCAA championships at Virginia, 275 wins and five championships in MLS — including three in four years with the Galaxy — and two World Cup appearances and 81 victories with the men’s national team.

Every number is a record, as are the 73 points the Revolution gathered this season, earning Arena his 13th postseason appearance and, almost certainly, his fourth coach of the year award. The only thing missing now is Arena’s sixth league title, which would tie him with the NFL’s Bill Belichick — with whom he also shares a stadium and an owner — for most championships for an active coach in a professional team sport in the U.S.

That’s something top-seeded New England, which received a first-round playoff bye, will begin chasing when it plays in the Eastern Conference semifinals Nov. 30. And it wouldn’t be wise to bet against the team since seven of Arena’s 13 full seasons as an MLS coach have ended in the league championship game.

That consistency is a hallmark of Arena’s success. Since taking over at the University of Virginia 43 years ago, he’s finished a full season with a losing record just once, going 8-9-1 in his third year with the Cavaliers. Two seasons later, that team won the national championship.

“Bruce is the most successful coach in the history of the United States. Full stop,” said Sunil Gulati, the only three-term president of the U.S. Soccer Federation and a former FIFA vice president.

“He clearly has a resume and a level of accomplishment that makes him the greatest coach in the history of the game in the United States,” agreed former AEG president Tim Leiweke, who hired Arena to coach the Galaxy.

Explaining what Arena has done, however, is far easier than explaining how he did it.

“If there was a secret, I’d write a book about it,” the coach, who is as acerbic as he is successful, spat dryly in a stout Brooklyn accent.

Actually it’s not a secret at all said Mike Magee, who played under Arena three times in two cities.

“I have the answer,” he declared. “He, better than anyone, recognizes winners. He surrounds himself with the best people then kind of lets them do their thing.

“He demands you be a good person, a good teammate, and understand your role. That makes it really simple. If you can’t do that, he kindly shows you the door.”

In separate conversations with nearly two dozen current and former players, coaches and executives, Magee’s theory was the one repeated most frequently. For all of Arena’s skills with strategy and tactics, the group agreed, it was the way he handled people that separated him for other coaches.

“What I’ve seen from Bruce evolve over the years is the human side, the human connection side, the relationship side,” said Gregg Berhalter, who played and coached under Arena with the Galaxy and national team before succeeding him as coach of the U.S. program. “He’s much more invested in the human being now and connecting with his players.

“He deeply cares for his players.”

David Beckham, who played for legacy coaches Alex Ferguson, Fabio Capello and Carlo Ancelotti, called Arena one of the best “man managers” he ever had.

“He knows the players and he knows what to do to win championships. His record proves that,” Beckham said. “Bruce brought an excitement to training. He brought an excitement to the games, around the locker room.”

::

It’s more complicated than that, of course, because Arena, who is also hyper-competitive, can be just as egotistical, demanding, sarcastic and mean as he is victorious.

“I don’t think you can compare Bruce to Ted Lasso,” Berhalter said. “That’s not a good comparison.”

In fact several people in Arena’s inner circle have, in private, described him with colorful and vulgar epithets. Yet all those people have followed him to multiple jobs.

“I’m sure there’s plenty of enemies out there,” Arena conceded.

Dave Sarachan, coach of the Puerto Rican national team, is one of those people who followed Arena to multiple jobs in nearly two decades as his top assistant at Virginia, with D.C. United, the Galaxy and in two stints with the national team. And while he is not one of those enemies, he agrees Arena is no Ted Lasso.

“Bruce doesn’t make it easy on anybody,” he said. “I could count on one hand the amount of compliments he might have given me.”

Yet minutes after telling that story, Sarachan’s voice cracks as he tells another. When his son Ian was born, Arena was the first person to show up at the hospital with gifts. And when Sarachan got married, Arena slipped the band a $100 bill to play the sappy Morris Albert love song “Feelings.”

“There was a side to him, through the gruff and rough and outside perspective, where he had sentiment,” Sarachan said.

“I sort of analogize that, like Simon and Garfunkel — me being Simon, by the way — we’ve made great music,” Sarachan continued. “But creatively, when you’re together, there’s just going to be some tension. There’s days that you don’t want to be around him. And he would probably say the same thing.”

Yet steadfast loyalty is an Arena trait, which is why coaches including Sarachan, Curt Onalfo and Richie Williams, his top assistant at New England, have done multiple stints with him, as have players such as Magee, A.J. DeLaGarza, Landon Donovan and Alan Gordon.

Perhaps no chapter of Arena’s coaching career highlights that better than the one involving Robbie Rogers, whose playing days appeared over at age 25 after Rogers came out as gay in a 408-word blog post following his release from English club Leeds United.

“I lost my love for the game,” said Rogers, who had played for the national team and won an MLS Cup with Columbus before moving to England. “I really believed there was no way I could be an out gay man and a professional athlete.”

When Rogers returned to California, Arena reached out with an open invitation to train with the Galaxy. Rogers waited nearly two months to accept but when he did, he was overwhelmed by the reception.

“He was just very supportive,” Rogers said. “Kudos to him for creating an environment where I felt that way. The second I stepped into the locker room he’s like ‘You should just stay and play with us’.”

He did, and 3½ months after hitting send on his blog post, Rogers made his Galaxy debut, becoming the first openly gay male athlete to compete in a major team sport in the U.S.

But that’s only half the story. Chicago owned Rogers’ MLS rights and the Fire wanted Magee in exchange for them. Arena came up with a win-win solution.

“I never wanted to be traded. He never wanted to trade me,” Magee, a Chicago native, remembered. “[But] I had some personal family issues and reasons why I had to get home.”

Magee finished 2013 with 21 goals and the league’s MVP award while a year later Rogers helped the Galaxy to their most recent MLS title. Slowed by injuries, Magee returned to the Galaxy — Arena offered him a two-year deal, Magee said, even though he knew he could play only one — where he and Rogers played their final MLS games alongside one another.

“He felt like everyone was family and he owed it to people,” Magee said, recalling multiple trades Arena made in which he left money on the table to send a player to the team of his choosing. “You know how unheard of that is?

“Coaches in this league will hang guys out to dry and not care. And then guess what? That sh— hits the fan in the playoffs.

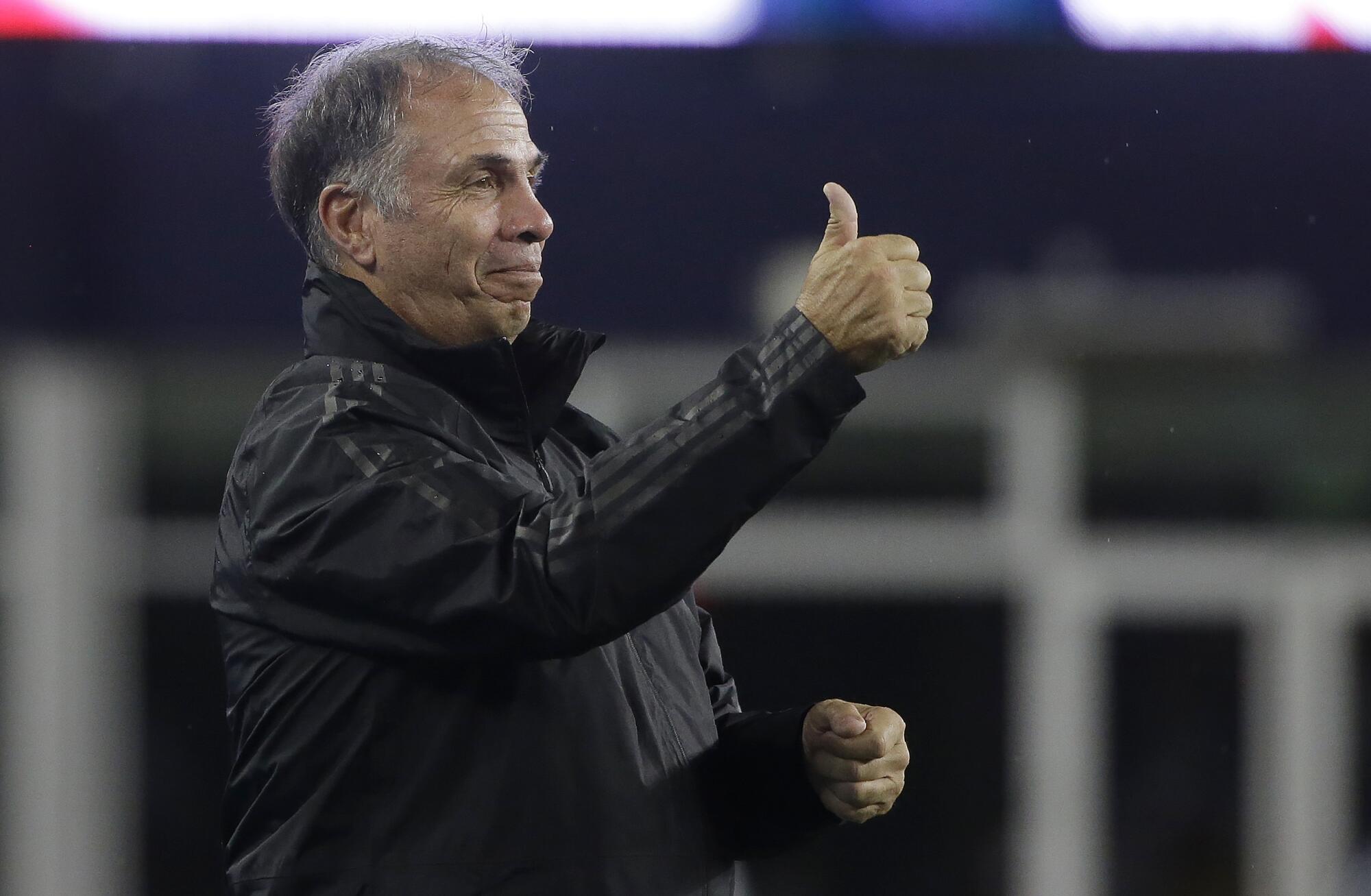

“You see how Bruce’s team plays? That’s purely creating an environment where guys just want to be there. If you have 11 guys on the field who would rather break their ankle than lose the game, you’re going find a way to succeed.”

Perhaps the most unusual think about Arena’s success, however, is the fact it was supposed to happen in lacrosse, not soccer. Arena grew up around soccer — his immigrant grandfather kept a poster of the Italian national team on the wall of his Brooklyn deli — and he went on to earn a cap with the U.S. and play one season as a goalkeeper in the short-lived American Soccer League.

But he favored lacrosse, winning gold and silver medals with the U.S. team in the world championship.

“Bruce was a far better lacrosse player than he was a soccer player,” said Kevin Payne, who gave Arena his first MLS coaching job with D.C. United and this year joined him in the National Soccer Hall of Fame. “But I think Bruce realized early on that there was a lot more opportunity in soccer. I don’t think now he would say lacrosse is his first love.”

::

It’s hard to pick a high point in Arena’s coaching career. Was it the five NCAA titles in six years at Virginia? The run to the World Cup quarterfinals in 2002, the best performance by a U.S. team in the modern era? Was it the three MLS titles in four seasons with the Galaxy?

But it’s easy to pick the low point. In 2016, Arena left the Galaxy and returned to the national team when Jurgen Klinsmann was fired with the U.S. winless two games into World Cup qualifying.

The team went 9-0-5 to start 2017 and was on the verge of qualifying for Russia when a 2-1 loss in Trinidad and a fluke last-second goal in Panama conspired to eliminate it from the World Cup for the first time since 1986.

Arena resigned three days later and spent the next year writing a book, doing some TV commentary and waiting for the phone to ring. When it didn’t, he offered to work with the Galaxy in an advisory role, thought he had a job in Columbus that fell through and offered to walk on as an assistant with LAFC.

The New England job wasn’t even on his radar when president Brian Bilello, his team off to a 2-8-2 start, called. Convincing Arena to take the job, he said, wasn’t difficult and the coach set about rebuilding the Revolution the same way he did the Galaxy.

Four months after Leiweke plucked him out of a college classroom to coach in Los Angeles, Arena remade the Galaxy roster, getting rid of more than 20 players and replacing them with solid locker room guys such as Todd Dunivant, Magee and Berhalter and drafting Maryland teammates Omar Gonzalez and DeLaGarza.

The team made the MLS Cup final the next season, starting a run in which it played in the championship game four times in six years.

He’s followed a similar blueprint in New England insisting, as he did with the Galaxy, on being coach and general manager, allowing him to bring in the players he wanted and build a team that fit his vision. Of the 27 men who were on the Revs’ roster in 2019, 15 are gone. Among the replacements are DeLaGarza and Ema Boateng, both of whom Arena coached with the Galaxy, along with Polish international Adam Buksa, whom Arena signed last year.

“One of his biggest assets is making sure there’s no ego on the team, that everybody knows their role,” said forward Teal Bunbury, whose 320 games in MLS are the most of anyone on the New England roster. “He’s brought together a group of guys that put the team first. It’s not necessarily always having the most talented players, even though we have a lot. But I think we all know what our roles are, and we all understand that it’s team first.”

And once that’s been established, Arena gets out of the way.

“He’s a guy that believes in the players he believes in,” DeLaGarza said. “He lets his players play freely. That, for a player, is what you want. He’s probably the best GM this league has ever seen. He’s getting the guys that he wants and he trusts and I think we all play for him.”

That unique approach to team building has allowed Arena to succeed in vastly different environments. While his big-budget Galaxy teams spent freely on the likes of Keane, Donovan and Beckham, New England’s payroll of $11.7 million ranks 20th in the 27-team league. But with the team’s three designated players, Buska, Carles Gil and Gustavo Bou, combining for 35 goals and 31 assists, nearly double the output of any other team’s designated players, the Revolution are the thriftiest team in MLS, spending just $160,000 a point.

But perhaps the best indicator of Arena’s influence is what happens to teams when he leaves. At Virginia, he won four national titles in his final five years before leaving in 1996; the school has been back to the final just three times since.

D.C. United made the MLS Cup final in each of Arena’s three seasons, winning it twice, before he left in 1998. The team has been back just twice since. And the Galaxy, which won three MLS Cups in Arena’s five seasons, have won just one playoff game in the five years since he left.

Another measure is the number of those who have learned at the hand of Bruce Almighty before going on to have success of their own as a coach, a list that includes four national team managers or assistants in Berhalter, Sarachan, Bradley and Keane; a Scottish Premiership winner in Steven Gerrard, now a Premier League manager at Aston Villa; MLS assistants in Williams, Onalfo and Pat Noonan; and a USL Championship manager in Donovan, who has taken the second-tier San Diego Loyal to the playoffs in his second season.

New England may soon have to prepare for a transition of its own. Arena, whose knees still bear the scars of knee replacement surgery, underwent a cardiac ablation operation last June to correct an arrhythmia. So while he has another season left on his contract, some people close to Arena think he may not come back if the Revolution win it all this season.

After all, what would be the point?

“He doesn’t really have much more to prove,” said Williams, a Revs assistant who played for Arena as a teenager at Virginia.

“He’s going to work as long as he wants to work. And he’s going to stop working when he doesn’t want to work anymore,” adds son Kenny Arena, an LAFC assistant who worked under his father with the Galaxy and U.S. team. “That’s going to be the question for him. It’s not going to be, ‘What’s the perfect ending to the story?’ “

There may be another chapter to the story, though. Although Arena said he has no regrets regarding his career, he does regret not using his public profile to do more to help others. His experience with Rogers, seeing what he had to go through every day as a gay man playing professional soccer, helped him realize that winning and losing wasn’t something that happened only on the field.

Food banks in the greater Boston area have become a particular focus for the coach, who now says turning around soccer clubs has been nice, but turning around lives would be an even nicer legacy.

“That’s something you learn from experience. You look at the world you’re living in and the rights and the wrongs and can you do something to help?” he said.

“What I do for a living is not real meaningful. You’d like to be able to do more in life than just be judged on winning games.”