LOMPOC, Calif. — California’s Central Coast boasts some of the most fertile farmland in the world, rich brown soil that produces a bounty of asparagus, broccoli, spinach, lettuce, artichokes, cabbage, kale and Brussels sprouts.

But getting that green gold out of the ground is exhausting, back-breaking work — something Julian Araujo learned at a young age. His father, Jorge, had followed his parents and brothers from Mexico into the farm fields around Lompoc when he was 15, picking the food that would fill other people’s dinner plates while barely earning enough to fill his own.

“Coming from a family of farmworkers, I was made aware at an early age of the hard work and the harsh conditions that the farmworkers experienced every day,” Julian said. “In the sun or rain, it didn’t matter. They were always working.”

The younger Araujo, 19, now works in the fields too, only his are the manicured soccer pitches on which the Galaxy and the men’s national team play. But he hasn’t forgotten the verdant fields he grew up around, nor the struggles of the people who work in them.

“I made a decision that when I was a professional, I would use my platform to show support for farmworkers and amplify struggles they face,” he said.

“They deserve more than they get.”

That’s why Araujo, wearing a blue face mask and his white No. 22 Galaxy jersey, came home Friday.

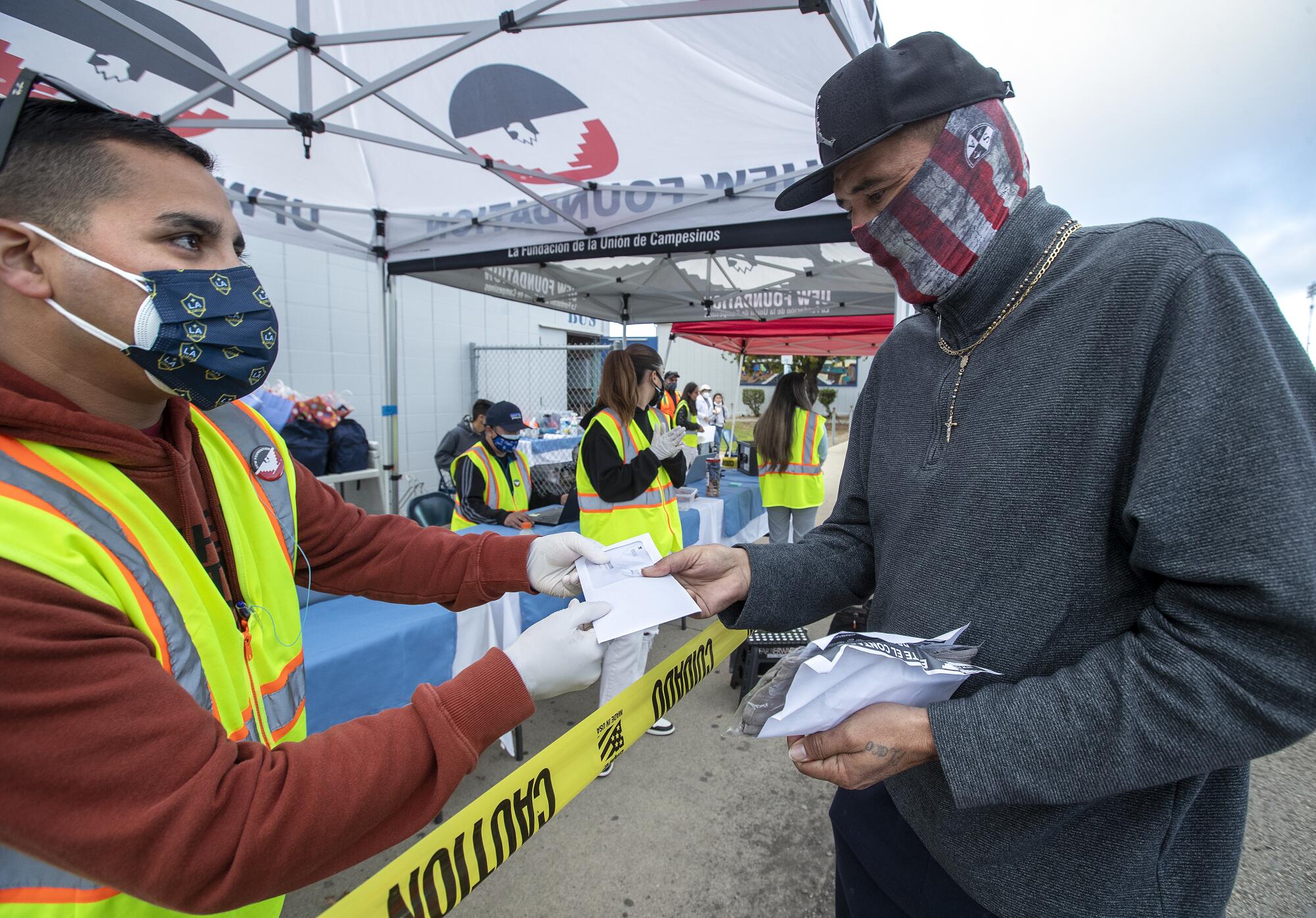

For more than 3½ hours, he and his family — joined by a group of about 20 volunteers — stood beneath canvas canopies in the parking lot of the high school he once attended, handing out about $26,000 worth of gift cards and backpacks filled with food and cloth face masks to farmworkers and others in need.

As Araujo distributed bags containing toothbrushes and other hygiene products, the Galaxy — which has thrown the weight of its charitable foundation behind the young player’s community work — raffled off soccer balls and made a financial contribution. Central to the effort were donations from the United Farm Workers Foundation.

In all about 150 families, or 600 people, received help.

It was the third time in the last eight months that Araujo has rallied to help essential workers he fears many have forgotten.

“I couldn’t just ignore the fact that was going on. Especially during this pandemic,” said Araujo, a once-shy kid who now speaks with purpose and maturity. “They deserve more recognition. They do a lot for our country. They provide for us, and I think we should provide for them.”

On Friday he did.

Some in the high school parking lot had come straight from the field — their boots and cotton work shirts dusted in soil — filing by in a socially distanced line under the mid-afternoon sun. There were still people there after the sun had set and a cool rain began to fall.

Maribel López, 25, a single mother who works for Velazquez Packing, was giddy after collecting a white envelope containing a $100 gift card.

“It’s been a difficult year. Everyone’s life has changed because of the virus,” she said in Spanish. “With this money we can buy the food that’s been missing from our table.”

Others weren’t so lucky, as the supplies ran out with people still waiting on line.

“The need is great out there. It still continues,” said Robert Perez, the emergency relief supervisor for the United Farm Workers Foundation.

Grinding poverty is no longer the greatest concern for agricultural workers — health experts say they are at high risk of contracting COVID-19. So in addition to the traditional hardships, workers now struggle to breath under face masks and bandanas, knowing that, with only the thinnest of social safety nets below them, catching the virus could prove devastating.

In addition to addressing people’s material needs, Perez said, Araujo’s commitment to the farmworkers has helped fill a spiritual one.

“It brings hope,” said Perez, who ends his text messages with ¡Si Se Puede! — yes we can — the rallying cry popularized by UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta.

“We have an individual from our community, a farm-working community, that is now a professional soccer player. Any type of inspiration, any role model like Julian is super important. When you combine it with the purpose of why we’re out there, it makes it even more powerful.”

Araujo’s campaign began last summer, inspired by a video of workers in Sonoma County harvesting grapes in 90-degree weather and the toxic smoke of a nearby wildfire. Working with his mother, he provided about 350 meals to front-line health workers, teachers and those in the fields around Lompoc. He later donated $1,700 to the UFW to kick off a fundraising campaign, using his Twitter account to raise more.

With the meals that were taken to the fields, Araujo included a note: “When the sun rises you go to work. When the sun goes down you continue working. Thank you for working with your hands, your mind and your heart.”

The Galaxy, who first learned of Araujo’s work through his social media posts, named him their Humanitarian of the Year, the first teenager to win the award. But he didn’t do it for the prizes.

“It does come from how he grew up, how he used to see my parents and my husband leaving so early in the morning, no matter the weather. Coming back tired,” said Araujo’s mother, Lupe, 49, a translator for the Lompoc Unified School District.

Jorge, 50, drove home the same point a different way.

“I always used to ask them, ‘What weighs more, a shovel or a pencil?’” he said in Spanish, recalling conversations with his children. “It’s better to work in an office. It’s better to get an education and keep moving forward.”

Araujo, the youngest of three, has never worked a day in an office — but he never had to wield a shovel either.

“Since he was 7 years old, maybe even younger, he would tell people: ‘I’m going to be a professional player,’” his mother said.

The road he had to follow was rugged.

His first big break came at age 16, when Barcelona, the Spanish megaclub, invited him for a weeklong tryout. That joy was cloaked in tragedy when, moments before the flight departed for Spain, Araujo received a text message that his best friend, the one who had urged him to make the trip, had been found dead.

He cried all the way to Europe.

Six months later Araujo was training with an age-group national team in Florida when his father called. He had cancer. It was bad.

Overnight Araujo’s long, methodical journey to professional soccer took on a new urgency: He had to get there quickly so Jorge could witness his MLS debut.

That came the following spring when Araujo, who should have been finishing his senior year at Lompoc High, was instead coming off the bench for the final five minutes of the Galaxy’s third game the 2019 season, making him the fourth-youngest player in franchise history.

As he left the field that night, Araujo tossed his sweat-soaked jersey to his mother.

Two years later his father, now a truck driver, has beaten back leukemia after a punishing series of chemotherapy treatments. And Araujo — who in his first season in 2019 earned a base salary of $80,000 (unlike other professional sports leagues, the MLS does not divulge salaries) — has been called up by the national team three times and received interest from iconic clubs such as Tottenham Hotspur and Juventus.

A contract with a professional European club of that caliber could pay him more in a year than his father has earned in his lifetime. It would also give him a platform for his charitable work stretching across multiple continents.

But the people who need help can’t wait — and neither can Araujo.

“I have a platform now and I want to use it. I don’t want to wait until I’m 20, 30, 40,” he said. “I’m just focused on right now because I may never get to a point where I’m making millions of dollars. My career can end tomorrow.

“I want to help today.”