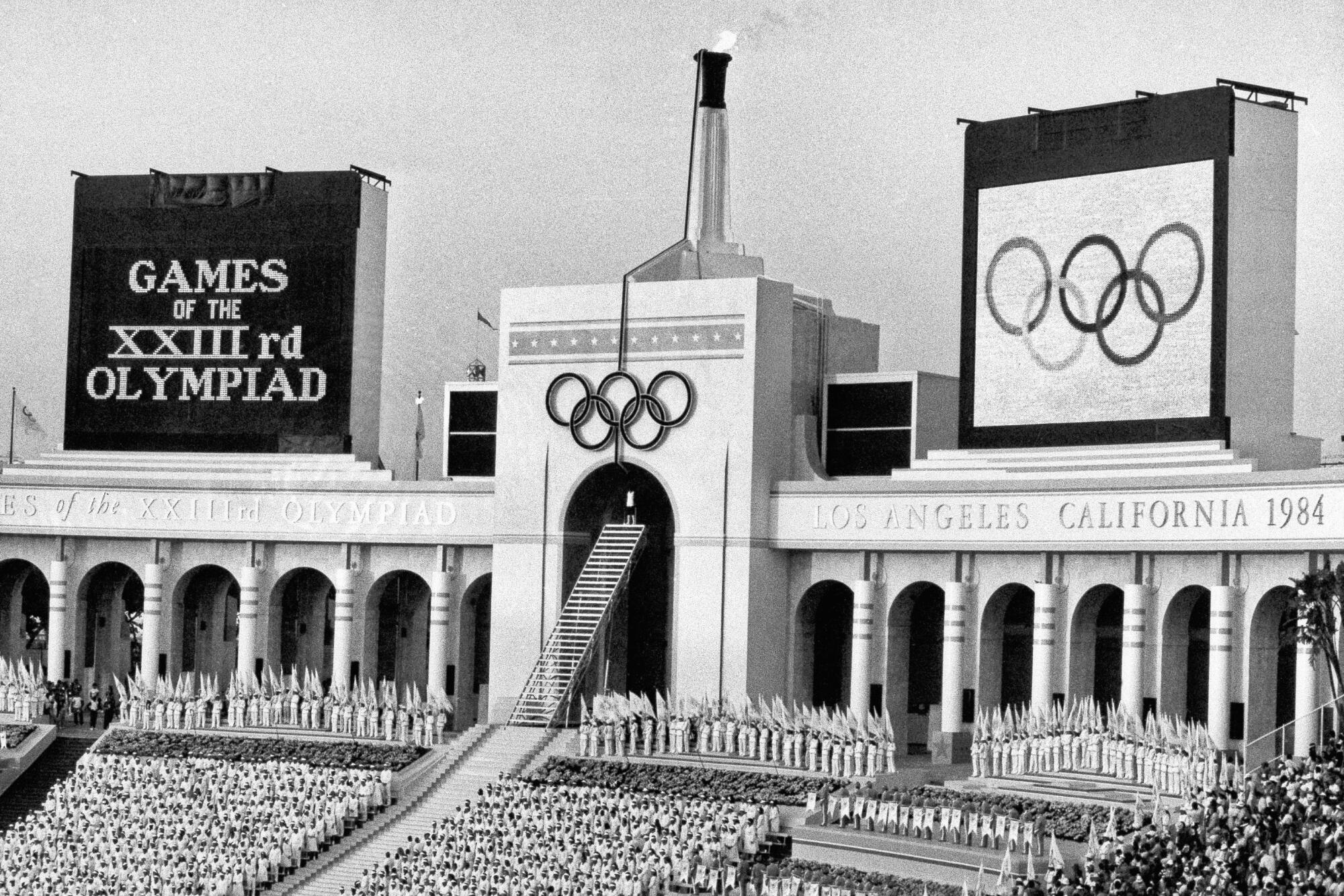

Saturday, July 28, 1984, date of the opening ceremony of the Los Angeles Olympic Games, was a huge day in the history of sports. It transcended athletics.

In the next day’s Los Angeles Times, under a large color photo of the L.A. Coliseum that showed hundreds of marchers holding balloons aloft to spell out ‘WELCOME,” sports journalism’s master of the written word told the world why.

Wrote Jim Murray: “An opening ceremony is not the start of the Olympics. It’s the culmination. It makes the Olympic statement. It’s a Valentine to tomorrow. Tomorrow will be all right. Tomorrow is in good hands.”

What Murray wrote was sentimentally hopeful, but also literally true. The torch was lit by Rafer Johnson, who not only had the good hands of a world-class athlete, but also a heart with a reach as high as the cauldron in the Coliseum’s peristyle end.

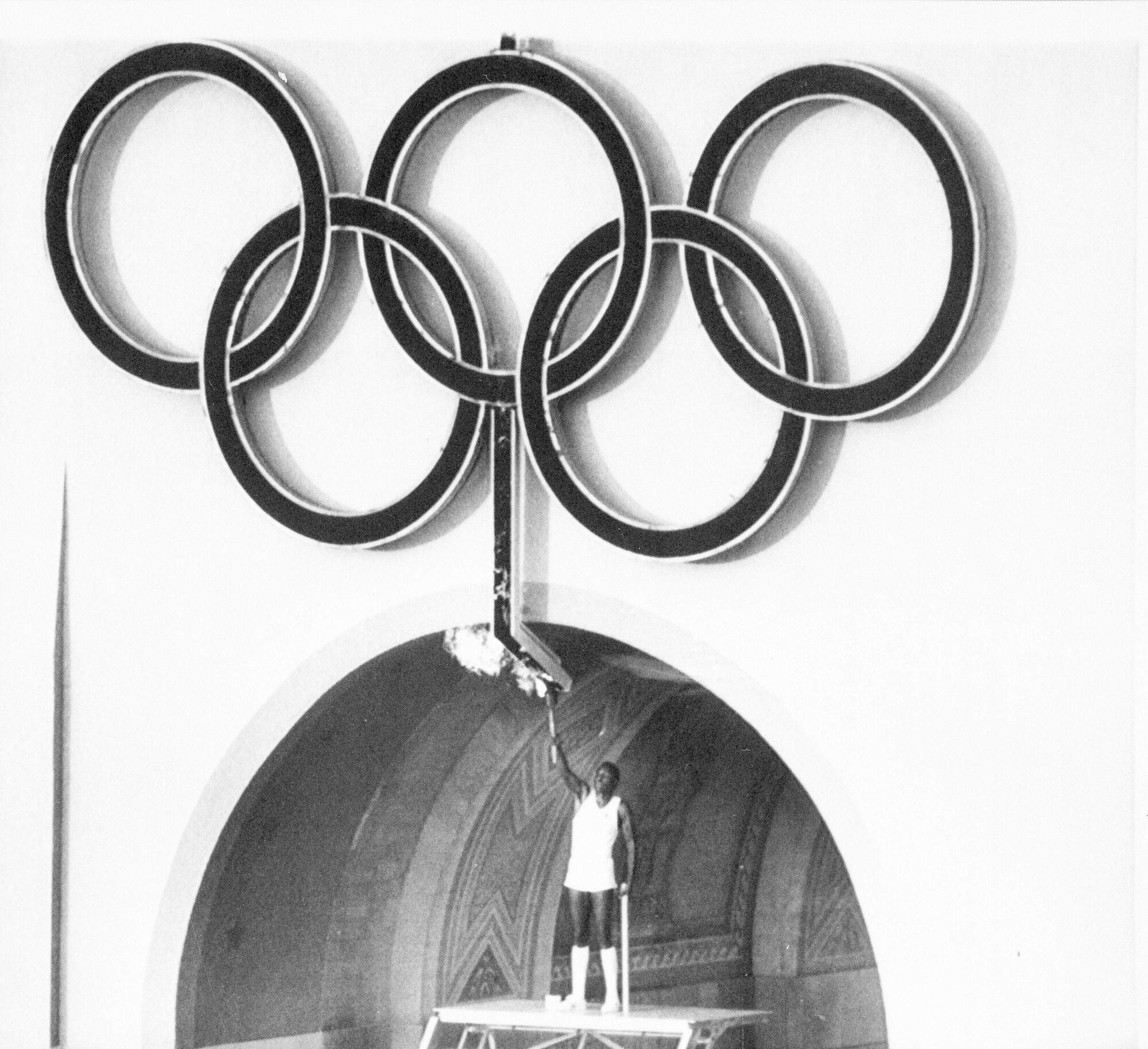

The world watched as Johnson climbed the 99 steps, torch in his right hand, left hand reaching down occasionally to balance himself on the narrow steps of the finishing ladder. When he turned to face the enormous crowd, he steadied himself with one hand on a vertical rail that had been installed the day before, at his request.

“I knew that, if I didn’t have something to grab on to, I might fall,” Johnson said.

In practice sessions, he never made it to the top. He was 48 years old, more than two decades since he won the Olympic gold medal in the decathlon at the 1960 Rome Games. He was in good shape, but not decathlon shape.

“When I got to the top and turned and saw that view, the huge crowd, it was breathtaking, a wow,” he said. “If I didn’t have that little rail to grab, I would have fallen.”

As he always had, in every walk of his life, Rafer Johnson rose to the occasion. He lifted the torch into the chute above his head that would send the flames upward, then spiraling through the five Olympic rings before shooting up into the cauldron. Once there, it would burn symbolically for the rest of the L.A. Olympic Games.

The Coliseum, venerable as well as creaky after 61 years of existence, had hosted dozens of great moments. This would be its second Olympics, the 1932 Games its first. Its walls had encircled everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Pope John Paul II. Nelson Mandela had spoken there. So had the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Billy Graham, John Fitzgerald and Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The first Super Bowl was there. So was Los Angeles’ first look at its beloved Dodgers.

Los Angeles Times sports columnist Bill Plaschke recalls his most memorable moments inside the 100-year-old Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

But this moment probably topped them all.

From a box seat area high above the Coliseum floor, President Ronald Reagan officially opened the Games. He was protected by bulletproof glass.

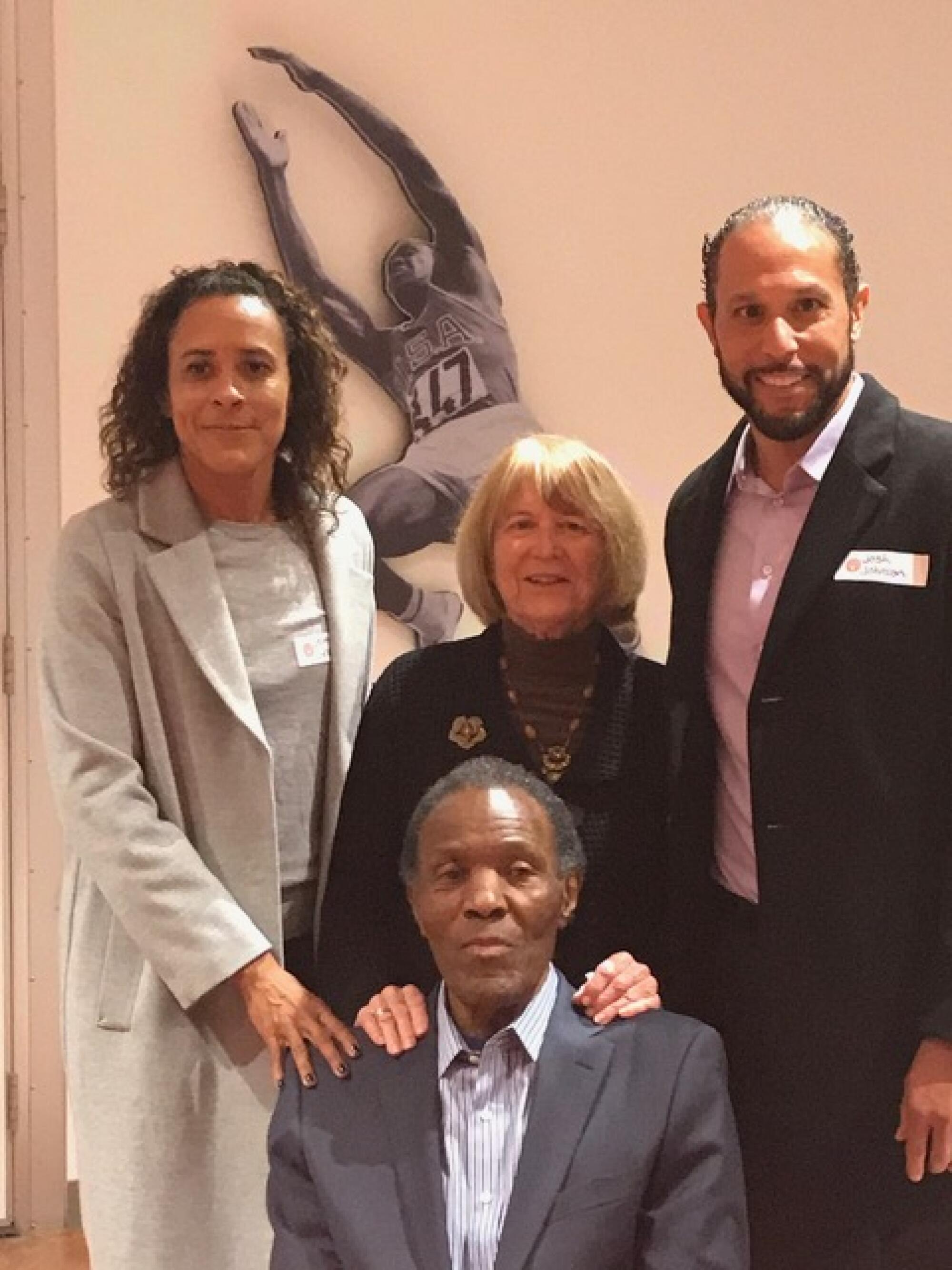

Under the press box, halfway up and around the 40-yard line toward the peristyle end, sat Rafer Johnson’s family. No bulletproof glass. Not even a full recognition quite yet of what was to come. Wife Betsy knew this would be a treasured moment. Daughter Jenny, 11, and son Josh, 9, were just catching on.

To this day, there remains some family disagreement about when the kids were told their dad would light the torch.

Jenny recalls, “He told us just before we got in the car to go to the stadium.”

Josh recalls differently. “I think it was in the car, right when we were going over the big hill on the 405 and heading downtown.”

Both Jenny and Josh are June babies. Jenny, a former Olympian in beach volleyball and now the head coach of UCLA’s beach volleyball team, turns 50. She finished fifth in the Sydney Games and is married to Kevin Jordan, former UCLA All-American wide receiver. Josh, a former Pac-10 javelin champion, currently works in commercial real estate, turns 48.

Three decades removed from that day, they both remember distinctly one thing.

Jenny says, “When he asked us who we thought would light the torch, we both guessed the same thing right away. Michael Jackson. Then I think we said Prince.”

Josh says, “I remember we both said Michael Jackson and I think we made up a Michael Jackson song about it.”

Betsy Johnson says that secrecy was of the utmost importance.

“Peter Ueberroth had sent a car for Rafer and picked him up right after he made a speech in the Valley,” she recalls. “When he got home, he told me and he also said that it had to be kept a secret. Peter wanted it that way. And the worst way to keep a secret is to tell your kids. They will tell other kids and the other kids will tell their parents and soon, you don’t have a secret.”

The stadium rocked and vibrated with pomp and circumstance. Athletes from around the world packed the field. Music played and people in the stands swayed to it. A rocket man lifted off and hovered above the stadium. Balloons were everywhere, reds and greens splashed on yellows and blues and the lovable old place became a human easel. Soon, Gina Hemphill, Jesse Owens’ granddaughter, was circling the track with a torch in her hand.

“That’s when I knew my dad would be last, when it really hit me,” Jenny Johnson says.

Her brother, Josh, says, “Climbing those stairs, that was the coolest thing. It never crossed my mind that he wouldn’t make it.”

Nor did their mother worry about that, even though she understood the physical toll it would take and had watched him train in the weeks leading up to the opening ceremony. He ran in a parking garage in Newport Beach, where they visited her parents. Nobody recognized him and put two and two together.

Over the past century, the Coliseum has been a cultural centerpiece for sprawling L.A., a place for sports, rock concerts, papal visits and even ski jumping.

Betsy had been in the stands in Rome in ’60, a 17-year-old with a little camera hanging around her neck, when he won perhaps the Games’ most memorable decathlon. She had met Johnson once, and was with her family on a trip to Europe. When she saw how he won the decathlon, it got her attention. Same with the rest of the world. Eleven years later, they were married.

“I knew there was no way he wouldn’t get up those steps,” Betsy Johnson says.

She knew from 13 years of marriage, which would become 49 years. She knew from all he achieved in life and how he handled his fame with his family.

There was never a trophy or a hint of memorabilia around the house.

“It was all in the garage,” Betsy says. “In the house, we had all the kid’s stuff. He made sure they were the special ones, not him.”

For a while, the gold medal from Rome, as well as the silver he won in ’56 in Melbourne, were tucked under their mattress. “I made him get a safe deposit box,” Betsy says.

He was in many movies and the kids were still the biggest deal in the Johnson household.

He wrestled the gun out of Sirhan Sirhan’s hand moments after Sirhan shot Bobby Kennedy at L.A.’s Ambassador hotel in 1968 and never felt any sense of heroics — only sadness that Kennedy died.

He started the California Special Olympics and treated its participants like he treated his family. Both took precedence.

“It was just cool. Even at 11 years old, I knew this was something special.”

— Jenny, daughter of Rafer Johnson, on her father lighting the Olympic flame in 1984

It was this lack of bravado that brought his children into a world of amazement when he lit the Olympic torch.

“I don’t think, for a long time,” Betsy Johnson says, “that they realized what he did or who he was.”

Jenny says that, not until after the torch lighting, did she start to get it. “I’m not sure I understood how beloved he was,” she says.

“The moment,” Josh says, “that he started climbing those stairs. That’s when I started to understand.”

The aftermath of the torch lighting brought more family perspective.

Josh says, “After that, he was like a rock star.”

Jenny says “It was just cool. Even at 11 years old, I knew this was something special.”

Betsy says her children suddenly saw the special nature of their father.

“I think Jenny liked it and clung closer to him,” she says. “Josh was a little frightened. Everywhere we went, to other events during the Games, there were people wanting pictures or autographs. Rafer never sat on the aisle and once, when we were leaving and he was surrounded by people, he tossed me the car keys and said he would meet us somewhere later.”

That was Rafer Johnson, protecting his family.

When he died Dec. 2, 2020, there was an outpouring of tributes appropriate of the man’s life and accomplishments. Newspaper articles filled the sports pages. Television went well beyond simple sound bites. Special stories about him were in abundance, and all were told.

But perhaps the most fitting tribute was a silent one. They lit the torch for a day at the Coliseum.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.