A legacy too great to forget as it’s 40 years since Seattle Slew won the Triple Crown

It’s difficult to say exactly when the excitement started to build about this super horse destined to be the only undefeated winner of the Triple Crown.

Some might say it was as soon as this son of Bold Reasoning and My Charmer was put up for sale as a yearling and bought for $17,500.

Or was it when the clocker at Saratoga recorded his workout but refused to put down the real time because it was so fast no one would believe him.

Or was it his devastating win as a 2-year-old in the Champagne Stakes at Belmont Park by almost 10 lengths.

Or maybe it was the night after the Champagne when trainer Billy Turner sat in a bar and told a reporter, “If he doesn’t win the Triple Crown, I haven’t done my job.”

Turner laughs when remembering that night.

“I couldn’t believe he wrote it,” Turner said. “Talk about sweating bullets. Talk about pressure.”

Saturday afternoon, when the winner of the Belmont Stakes crosses the finish line, it will mark the 40th anniversary of Seattle Slew’s magnificent run to glory. As good as he was on the track, he was equally as great as a sire with offspring such as A.P. Indy and Slew O’ Gold.

He touched many lives and became a true national celebrity. He had lots of personality. He liked things his own way. But he also had his soft side.

It all started when Karen and Mickey Taylor joined with Sally and Jim Hill and bought one of the greatest racehorses in American history.

Mickey Taylor was at the Fasig-Tipton Newtown Paddock sale in Lexington, Ky., as Jim Hill, a veterinarian, had to go back to New York to operate on a horse the next day.

“I remember I told Mick, go short on the other horses because the one we really want is the Bold Reasoning colt,” Jim Hill recalled.

The Hills were lying in bed when the phone rang.

“It was Mickey and Jim said: ‘Did we get him? What did we have to pay?’” Sally Hill remembered.

The $17,500 was high for this particular sale but well below the prices at the summer Keeneland sales.

“Jim then told Mickey, ‘It’ll be the biggest bargain in history,’” Sally Hill said. “Then he rolled over to me and said ‘We just bought ourselves a champion,’ and I just laughed.”

Seattle Slew, named after Taylor’s Northwest logging roots, was not perfectly conformed but everyone knew he was something special.

“He was always our favorite, the moment he walked out of the stall,” Mickey Taylor said. “But he had all the pizzazz in the world. He was very awkward looking. He was raw boned and very young but we knew he would mature.”

Slew hadn’t even made his first start at Saratoga before he was turning heads.

“He had to have a gate work to run there,” Mickey Taylor said. “The clockers were there and the official one had him at 33 and three fifth [seconds] over three eighths [of a mile]. He said, ‘I can’t put that time down. People will think I’m crazy.’ So he put down 36.”

Slew’s first start was delayed when he kicked his hind leg into the wall of his stall one morning. So it was on to Belmont Park.

He won his first race on Sept 20, 1976, a six-furlong maiden special weight by five lengths.

“Before his second race, our phone rang and it was [trainer] LeRoy Jolley,” Sally Hill said. “’Wow, LeRoy, thanks very much, it’s a great offer but I think we’re going to pass,’ Jim said. LeRoy was buying for one of his clients. I asked him what was the offer. ‘A million dollars.’

“Couldn’t we even discuss this? A million dollars was a lot of money back then. Thanks goodness he didn’t sell him.”

He came back on Oct. 5 to win a seven-furlong allowance race by 3 ½. Then 11 days later he won the one-mile Champagne Stakes by 9 ¾.

“I told Karen when he passed the finish line and before we went to the winner’s circle,” Mickey Taylor said, “if we can keep this horse sound, I’ll never cut down another tree in my life.”

By this point Slew was developing his personality.

“He was very easygoing,” trainer Turner said. “He liked people but he wasn’t lovey dovey. He didn’t like people petting him. He was the boss hoss. He would stand back and just look at you. He would let you do whatever you wanted him to do, but only if he wanted to do it.”

Sally Hill remembers there used to be a radio outside his stall.

“He didn’t like it if somebody changed the station,” she said. “He would put his head out and get mad and mess with the radio. He liked country and western.”

Animals like routines, but Slew set his own.

“Every morning he would go to the track, he had to pick the way to the track,” Sally Hill said. “Some days he’d stop at a barn that had a goat or a chicken and he would wait for the goat to come out. Then he would just look at him. He would watch airplanes bound for Kennedy. But the minute he hit the track, he was a complete professional.”

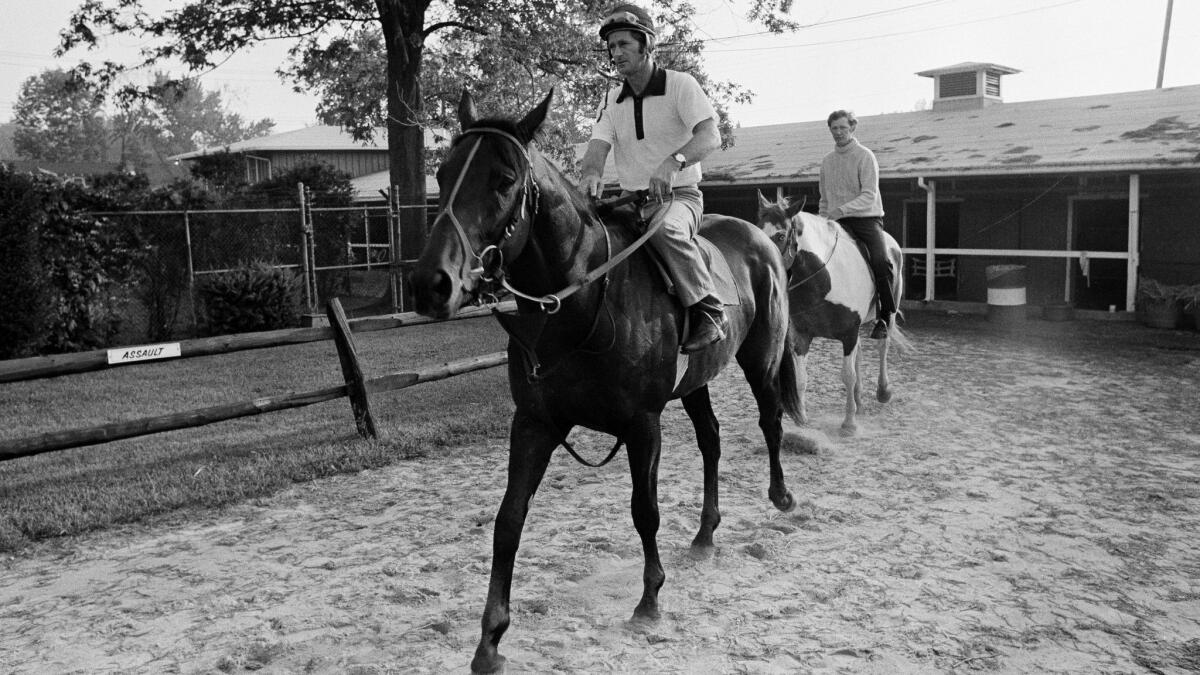

No one knew that better than Mike Kennedy, the only regular exercise rider he ever had.

“I thought he was a very businesslike horse,” Kennedy said. “He worked in a very professional manner. But he was tough. He pulled hard. You had to keep him from running off all the time. He was a little contrarian in the stall. He didn’t like to be fussed with, especially if he didn’t know you.”

Karen Taylor remembers his impact on the track.

“He’s like Muhammad Ali, he psychs out all the other horses,” she said. “When he gives you the evil eye, he just dares you to come past him. Not just horses, but he would look the jockeys down.”

He’s like Muhammad Ali, he psychs out all the other horses.

— Sally Hill on Seattle Slew

Sally Hill thought of the time when her son Jamie was 4 years old and went missing around the barns.

“I was looking around everywhere,” she said. “I finally asked somebody, ‘Have you seen Jamie?’ They said they thought they saw him near Slew’s stall. And there he was curled up and asleep in the straw in the corner of the stall and Slew was there nuzzling him.”

Slew had some time off at the end of his 2-year-old year and was shipped to Hialeah to start his Derby prep trail.

He won a seven-furlong allowance race by nine lengths. Then the 1 1/8-mile Flamingo by four. He shipped to New York and won the Wood Memorial by 3¼.

It was on to the Kentucky Derby.

Mickey Taylor was always concerned about security. When he found the night watchman asleep at Hialeah he enlisted his parents to move their camper next to the barns and keep an eye on things.

But there was a problem when they arrived in Louisville, Ky.

“They told me I wasn’t going to put that camper on the grounds of Churchill Downs,” Mickey Taylor said. “They asked me when I was coming and I said we weren’t.

“We’re about halfway over to the barns and they call [director of horseman’s relations Julian] “Buck” Wheat and tell him ‘You can tell Mr. Taylor he can do anything he wants.’”

Would Taylor have gone through on that threat?

“I guess we’ll never know,” he said.

The night before the race Mickey Taylor’s phone rang at 3 a.m. It was his mother. She said he had to get to the barn immediately.

“Karen and I get there and my dad had this ex-night watchman by the throat,” Mickey Taylor said. “Someone else had [groom] John Polston in a headlock. And it was all by my parents’ camper. I look down and I see alfalfa by Slew’s stall. If he eats alfalfa and drinks water it could blow up in his stomach. I go down to the stall and Slew is lying down in my mom’s lap.”

Churchill Downs was mobbed on race day, as it was most every time Slew ran from that point on.

“I walked out of the paddock with the horse and there were so many people,” Turner said. “I had reporters and photographers with me, 50, 60, 70 of them. I didn’t have any idea how to get to my seat. So I ducked off the path into the first floor of the grandstand and went to a bar where there was a television. That’s where I watched the race.”

Slew broke poorly in part because the assistant starter didn’t have his head pointed straight.

“It was an inadvertent hold,” Jim Hill said. “It was a very quick gate. He broke last and I tried not to throw up. By the time he got to the finish line [the first time around] he had a head in front.”

Slew won the race by 1¾ lengths.

Turner didn’t go to the winner’s circle in either the Derby or the Preakness.

“I was superstitious because I thought I really hadn’t done anything until I won the Triple Crown,” he said.

The owners had their entourage in Louisville.

“We had to run second just to pay for the tickets,” Sally Hill said. “We had over 100 people. We had to charter buses. One of the things you don’t do is plan a party ahead of time. But you can’t take that many people to a restaurant after the Derby in Louisville.”

She got the Churchill Downs caterer to set up a room — should a certain thing happen — and they held a party for 135 of their closest friends. The menu: steak, baked potato, salad, and most importantly, an open bar.

The Preakness is always a more pleasurable experience than the Derby.

“What the Derby thinks it is, that’s what the Preakness is,” Mickey Taylor said. “My mom and dad and their camper were welcome. They were given food. They didn’t have to cook in the camper. The stall was spotless. It was delightful.”

Chick Lang was the beloved general manager of Pimlico and Laurel, known as the Maryland Jockey Club. People coming to the second leg knew almost everything would be taken care of.

“Chick Lang was so kind,” Sally Hill said. “We had 90 people at the Preakness. He cleared out some offices and had a lunch for all of us. Crabcakes and stuff. At one point I told the guy in charge there was something I couldn’t talk to him about. He said, ‘We’ve already taken care of it [the post-race party].’”

Because the paddock was essentially in the covered area of the grandstand, Jim Hill was concerned that the crush of people could be a problem for Slew. He suggested that it be moved to the grass course on the outside of the dirt course so that everyone could see the saddling.

It remains that way to this day.

The race was pretty uneventful, with Slew winning by 1½ lengths. It could have been more but there was no need to push the horse considering the Belmont was three weeks away.

The Slew Crew, as they were called, got to Belmont; the track was in the midst of a parimutuel clerk strike.

The problem with that was exercise rider Kennedy was a member of the union and couldn’t be seen crossing the picket line.

Turner tried two other exercise riders, including regular jockey Jean Cruguet, but neither could moderate the horse and keep him from taking off.

“When it was time to do some serious galloping, Mickey told Billy he had to get me in there,” Kennedy said.

Legend has it that they snuck Kennedy on the grounds in the trunk of Turner’s car.

“It’s a good story but it didn’t happen that way,” Kennedy said with a chuckle. “Actually I was in the car but slumped down so nobody could see me. They drove me around to the house of [trainer] Sally Bailey which was right next to the grounds. There was a gate at the back of the house and I went through that onto the track.

“It was pretty obvious when I got on the horse. Someone yelled, ‘I thought you were on strike.’ I told them it was just settled.”

Kennedy wasn’t far from wrong. It settled later that afternoon.

The time flew by, with everyone waiting to see if this unbeatable horse could handle the 1½-mile race.

As race time approached, all the horses were in the paddock but one, the only one that counted.

The track had allowed cars to park all over the backside, making it difficult for Slew to get there, especially since Turner didn’t want him in the paddock a minute before he had to be there.

“So they had to take a circuitous route,” Sally Hill said. “Turner was fined. We paid the fine. They weren’t going to run the race without him.”

The connections felt various emotions when the colt crossed the finish line to become the 10th horse to achieve the near impossible — win three major races in five weeks.

The most common emotion was relief.

“When we went back to the barn, we cooled him out and put him away,” Turner said. “I ducked into a stall and broke down and cried. It was such a relief, because the pressure was off.”

Slew was due some time off but Marje Everett, owner of Hollywood Park, had other plans. She was going to do what it took to get Seattle Slew to race in Inglewood.

And here’s where the stories vary.

The owners and Kennedy say everyone, including Turner, was in favor of going to the race. Turner says he was opposed to it.

Kennedy, who wasn’t asked, said he went to Turner with his opinion.

“I told Billy the horse was tired,” Kennedy said. “He said, ‘don’t upset the troops’ and he was the one training the horse. He was so tired before he went to California that my daughter could have ridden him, and she doesn’t ride.”

Turner said he was opposed to racing him at Hollywood Park because the horse was mentally tired.

Slew was beaten for the first time as he ran fourth in his last race as a 3-year-old.

Mickey Taylor said the problem was that Slew was tranquilized twice when he was shipped to Los Angeles and hadn’t recovered. Jim Hill, the vet, said that was nonsense.

Pretty much everyone regrets running him in that race.

Slew ran seven more times before he retired, winning five of them. The biggest win was the 1978 Marlboro Cup where he beat Affirmed. They are the only two Triple Crown winners to ever run against each other.

Slew went off to the breeding shed with great success. He stood at Spendthrift Farm and Three Chimneys Farm.

The Taylors and Hills had a falling out over the assets of the horse, resulting in litigation in 1997.

“It was very painful,” Sally Hill said. “That was about as tough a thing as I’ve ever had to face.”

Slew started having medical problems and in 2000 had surgery to alleviate pressure on his neck.

“I looked after him 27 years, 9 months and 18 days and the last three years of his life,” Mickey Taylor said. “I was with him every day [the last three years], except for one day when my mother passed away.”

In April 2002, the Taylors moved him to Hill ’n’ Dale Farm to live out his last days.

Slew had a companion his last couple years, a black Labrador called Chet, named after Mickey Taylor’s father.

“Slew didn’t like dogs,” Mickey Taylor said. “If there was a dog in his stall he wasn’t there long. But he was different with Chet.”

On May 7, Slew was slipping away. Mickey went to find Chet to bring him to the stall to see Slew, where Karen and his longtime groom Tom Wade were waiting.

“Slew is laying down in Karen’s arms,” Mickey said. “Chet walks in and he looks up and they make contact, eye to eye. Slew raised up on his sternum. I turned Chet loose and he just stood there.”

Chet then went over and licked Slew, who reciprocated. They went nose to nose and licked each other again.

“Something passed between Slew and Chet,” Karen Taylor said. “It was like they were talking.”

Slew put his head down in Karen’s lap, closed his eyes and passed away.

It was exactly 25 years to the day that Seattle Slew won the Kentucky Derby.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.