‘Albanian Bear’ Reshat Mati is always up for a fight

The friendly 14-year-old from Staten Island is a fierce boxing and martial arts competitor. After numerous bouts and amateur titles, he’s gained international notice and an Internet following.

The first hint of a bruise, blackish and glossy, appears under Reshat Mati's eye as he finishes a jujitsu workout. It seems that he took a knee to the face.

Someone offers to get an ice pack, but there isn't time. Reshat hurries off to another gym, a storefront several miles away where the windows steam up from all the boxers generating heat inside.

By 9:30 p.m., he has pulled on gloves and headgear to spar with a larger, more experienced opponent who likes to fight from close range with lots of banging elbows.

Though Reshat stands only 5 feet 4 and is a slender 110 pounds, he refuses to back down. The other guy hits him and he answers bang-bang with two hard punches of his own.

"There is nowhere I'd rather be," he says later. "This is my life."

It is an odd existence for a 14-year-old from Staten Island, a youngster with a smile full of braces and a friendly, chatty manner.

Most nights, as other boys settle down to watch television or text friends, Reshat travels with his father from gym to gym. His love of boxing, martial arts and wrestling — any kind of hand-to-hand combat — began when he was a toddler.

People in the fight game, seeing that he has accumulated almost 200 bouts and dozens of amateur titles in various disciplines, wonder if they are looking at a future champ. Videos of him in action attract millions of views on the Internet.

Something about the kid changes when he steps into the ring. His smile tightens into a grimace. Even Reshat struggles to describe the innate ferocity that takes over, the thing that makes people call him the "Albanian Bear."

Maybe fighting runs in his blood.

His grandfather learned to box in the Albanian military, then taught Reshat's father, who recalls there wasn't much else to do while growing up in mountainous terrain near the country's eastern border.

Reshat Mati, a 14-year-old who is ranked No. 1 in the world in his age division by the International Kickboxing Federation, puts on his headgear before a kickboxing workout at Bars gym in Staten Island. (Michael Nagle / For The Times) More photos

"There were no video games," Adrian Mati says. "The only thing we had was wrestling and boxing."

Immigrating to the U.S. in the 1980s, Adrian started a family with his wife, Ajshe, and decided to pass along the sport to his children.

His eldest, Diana, boxed until she was 12. After that, he says, "she got into makeup and nail polish." A middle daughter, Lenora, showed no interest.

Reshat, the youngest, was a different story. Adrian and Ajshe called him "the punching baby" because he would lie in his crib throwing crude facsimiles of hooks and uppercuts.

"I started teaching him when he was 2," Adrian says. "As he's getting older, we do a little bit more and a little bit more, and he liked it."

Reshat started taking self-defense classes at age 4 and was enthralled. He recalls sparring with a classmate.

"I hit him with a body shot and he dropped," he says. "I felt bad for the kid, but everyone started paying attention to me."

Within a year, he had won his first tournament and acquired a reputation for fierceness. Video from a 2008 submission grappling tournament — the sport features elements of martial arts and wrestling — shows him ducking low to grab his opponent by the legs, lifting the boy onto one shoulder and slamming him down to the mat.

In other footage, a 10-year-old Reshat drives relentlessly across the boxing ring, heedless of the punches that come his way.

"He's not afraid to get hit," says Aureliano Sosa, one of his coaches. "He's willing to take a shot to give three or four. Other kids won't do that."

Reshat Mati poses for a portrait at home in Staten Island in his room filled with championship belts and awards. Reshat says he doesn't crave celebrity. "When I win, I'm happy," he says. (Michael Nagle / For The Times) More photos

The International Kickboxing Federation lists Reshat at No. 1 in the world for his age division, and he has reached the finals in two of the last three Silver Gloves national boxing championships. A high school freshman, he could not afford to miss class for this year's tournament in Missouri.

Proof of his success covers the walls of his bedroom in a tidy home just up the hill from where Hurricane Sandy's floodwaters crested last fall. Dozens of title belts — the kind made from colorful leather with oversized, shiny center plates — leave no space for other decorations.

"He's starting to see the rewards," his father says. "That's what drives him."

Reshat dismisses any suggestion that he craves celebrity. As he puts it, "When I win, I'm happy."

Two years ago, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued a policy statement that discouraged boxing for children and adolescents. The academy cited potential risks: concussion, chronic neurologic injury, death.

Either you hurt him or he's going to hurt you."— Adrian Mati, Reshat's father

The decree made no mention of other sports that Reshat favors, including his beloved mixed martial arts.

With competitors wearing minimal padding as they punch and kick each other in a caged ring, MMA has been called "human cockfighting" by U.S. Sen. John McCain. It is banned in New York, forcing Reshat to travel to nearby states in search of matches.

Youth MMA differs from the professional version on television. There is no cage, just a mat with spectators gathered around.

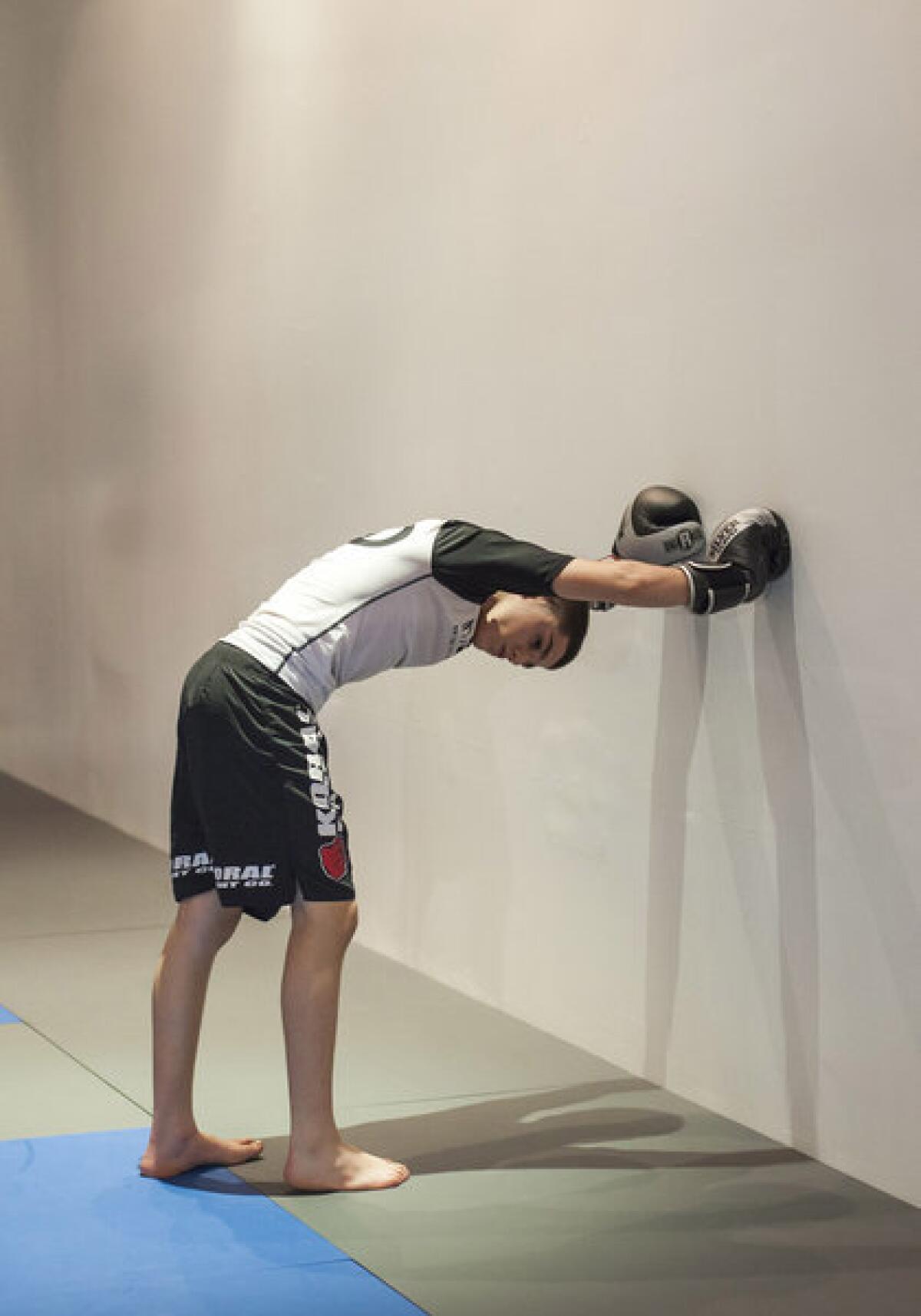

Reshat Mati stretches against a wall during a training session for Brazilian jujitsu, a martial art that specializes in grappling and ground tactics. (Michael Nagle / For The Times) More photos

Still, it is brutal, even for a kid who yearns to fight. Reshat remembers an incident four or five years ago in New Jersey. Knocking his opponent to the ground, Reshat jumped on top and wrestled himself into position to whale away. There was only one problem.

"Dad," he yelled, "he's not fighting back."

From early on, Adrian had spoken plainly about what he calls a "hurting sport." He had often said: "You've got two choices — either you hurt him or he's going to hurt you."

At the New Jersey match, the father urged his son to let loose and Reshat began throwing punches hard enough to make his opponent's head bounce off the mat. The other boy was not injured, but by the time the referee stepped in, Reshat's expression had changed.

"He was about to cry," Adrian says. "He kept telling the other kid, 'I'm sorry, I'm sorry.'"

But such misgivings are rare. Reshat mostly thinks of punching and kicking in technical terms, and is always searching for the best angles and leverage.

His parents insist that fighting is no more violent than football or hockey. They mention the time their son tried soccer, at age 7, and broke a toe.

He kept telling the other kid, 'I'm sorry, I'm sorry.'"— Adrian Mati, Reshat's father

"You can get hurt playing anything," Adrian says.

So far in his career, Reshat has been hit flush only once, suffering a head shot that left him dazed. It stung, but he accepts that pain is part of the sport.

Training five days a week, he often wakes up sore the next morning. There is nothing to do but shake it off.

The NYC Cops & Kids Boxing Club is located in a basement in a shabby part of Brooklyn. Rap music echoes off the concrete walls. The club serves as Reshat's home base, the cornerstone of a regimen that includes several gyms and coaches that cost his parents $150 to $250 a month.

Money is only part of the commitment. Adrian, a construction and security worker on disability from a job accident, must ferry his son around. On days when Reshat does not train in Brooklyn, he often pulls double duty at two gyms closer to home.

One of them, the Brazilian jujitsu studio, is quiet and softly lighted, the floors covered with an expanse of clean, blue mats. The head instructor, Joseph Capizzi, teaches takedowns that come in handy during MMA matches.

As they spar, Reshat flicks a couple of jabs, then dives to grab Capizzi below the waist. They tumble across the floor, a mishmash of arms and legs.

"There are many guys who come in here and try hard, they break a sweat, but it's different with a champion," the coach says. "Reshat comes in and pays attention and walks away with something new each time. I've never seen him throw a lazy punch or a fake kick in six years."

So when Reshat catches that inadvertent knee to the face, he shrugs it off. With a national boxing tournament on the schedule, and an international MMA competition next fall, there is much work to do. He soon leaves for the Bars gym to practice boxing and kickboxing.

The simplicity of using only hands and feet appeals to him. He likes individual competition, likes not having to rely on anyone else to win. There is a visceral thrill.

"I'm not going to lie," he says. "Before I get in the ring, I get a little nervous."

By 10 p.m., he has worked his way through several sparring partners. Then, with the place emptying out, he stays a little longer to practice with a coach.

Akmal Zakirov, a former kickboxing champion from Uzbekistan, barks commands — "body, head" — pushing the teen through one more timed round.

Reshat's feet dance across the mat, his shoulders dipping and weaving. He finishes with a one-two combination and a kick to the body, then slumps away with his head down, exhausted but content.

Follow David Wharton, @LATimesWharton, on Twitter

More great reads:

A student with promise, a teacher who had to help

Timbuktu calligrapher keeps ancient learning alive

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.