Teacher pays it forward on immigrant’s path to education

Brought to the U.S. from Mexico as a baby, Itzel Ortega had no way to get financial aid to become an architect. Then her eighth-grade teacher, recalling her own story, stepped in.

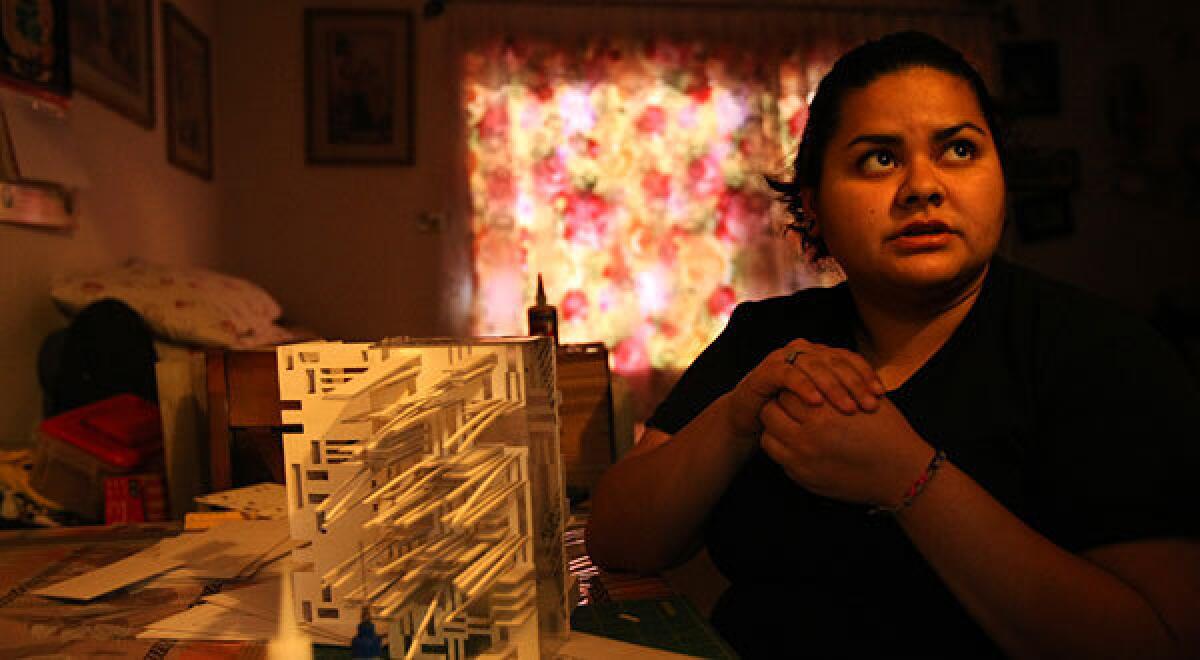

Itzel Ortega should have been bursting with the good news. Instead, her eyes filled with tears as she confided in her former English teacher.

She had just been accepted to the architecture program at Cal Poly Pomona. But she wasn't eligible for financial aid. She was six months old when she crossed the border illegally, carried in her mother's arms.

There seemed to be just one way to come up with the money: Her father would get a second job. This was why he came to America — to provide a better future for his children. As a busboy, he was on his feet all day, chopping vegetables, wiping tables and washing dishes. Now, he would work even harder.

As Ortega spoke, Leticia Arreola thought of her own father, also a Mexican immigrant, also a restaurant worker. She remembered his footsteps in the hallway late at night after a long day — quick in the early years, slower as he aged.

Arreola saw potential in all her students at El Monte's Potrero Elementary, but Ortega, especially, seemed destined for greatness. She was creative and meticulous, outstanding at every subject. The two had kept in touch since Ortega was a star in Arreola's eighth-grade class.

Ortega had gone to her former teacher's classroom to unburden herself, not to ask for help. But in the days that followed, Arreola couldn't stop thinking about Ortega's father and those extra shifts. She kept hearing her own father's footsteps.

Fidel Arreola had come from Mexico illegally at the age of 17, working as a cook at the Velvet Turtle before opening his own restaurant, Ely's, in Monrovia. He eventually got his papers. Leticia and her brother were born here.

Her father worked 16 hours a day, seven days a week for 10 years without a vacation, saving for his children's college education. During their years at UC Santa Barbara and UCLA, they never had to worry about money.

Arreola was single with no children and no mortgage. She lived with her parents. Her teacher's salary was modest, but she had few expenses. Her Christian faith told her to give without expecting anything in return. If she was going to help, she would go all the way.

She picked up her phone and texted: "I'm not going to let you not go to college."

Itzel Ortega's elementary school and college ID cards are shown with documentation of her life in California. She used the materials in her application under a program for immigrants who came to the United States illegally at a young age. Those who qualify will receive work permits and a two-year reprieve from deportation. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

At first, Ortega couldn't believe it. Arreola was promising to cover the whole cost — about $7,000 a year, for five years. She would give her former student the same gift she received from her own father.

"My parents came here and had their own season of being undocumented," said Arreola, 40. "I know what it is to work in a kitchen, and to think of him having another job...."

Ortega's father says she must repay the debt — not with money, but by being like a daughter to Arreola.

When Arreola works late, her former student runs over to the school with dinner. The Ortegas always reserve some Christmas tamales for her. They have no other way to thank her.

Petite with olive skin and large, dark eyes, Arreola looks young for her age. For Ortega, she's like a cool aunt: someone to joke with, but someone who is also a source of serious advice. The two attend church together in Monrovia on Sundays.

When Ortega was deciding between architecture and English, Arreola asked which she liked better. The answer was: both. Arreola suggested architecture, reasoning that architects can make more money than English professors.

"It's easier to tell her than my mom," said Ortega, 24. "My mom gets worried about everything."

But there is still an element of reserve. At pivotal moments, they communicate by text rather than revealing emotions face to face. And Ortega can't break the habit of addressing her former teacher as "Ms. Arreola," even as their bond has solidified.

At lunch in Old Town Monrovia one day after church, they joked about what will happen when Arreola gets old. The conversation was lighthearted, but both adhere to traditional Mexican values in looking after their elders.

My brother is Mexican American. The world handed us different cards. His cards are better. He's a real American. I don't feel like I can claim it."— Itzel Ortega

"You can visit me once a week in the old folks' home," Arreola said.

"I'm not going to put you in a home," Ortega shot back. "I'll build a guesthouse. You can be the weird aunt in the back."

In more than two decades in California, the Ortegas have lived carefully, frugally, steadily. They have no car, because it is too risky to be caught driving without a license. They lived in the same cramped bungalow, three children in the only bedroom and the parents sleeping in the living room.

Mr. Ortega, who asked that his full name not be used because he is in the country illegally, worked at a Vietnamese restaurant downtown for 15 years until it closed. He is now a busboy at another Vietnamese place closer to home.

Mrs. Ortega, a stay-at-home mom, is so shy she won't look a visitor in the eye. Instead, she places an extra pastry on the kitchen table and packs an extra breaded steak sandwich to go. When her children were younger, she inspected their homework, insisting that it look neat, even though she couldn't understand the English on the pages.

Ortega wears her wavy hair long and favors dark jeans with Converse sneakers. She is always working, building models with an X-Acto knife and glue, writing papers and preparing group projects; slacking off is not an option.

"I have so many people invested in it," she said. "They have a lot of hope in me. I can't let them down."

She has no memory of the town in Michoacan where she was born. El Monte is all she has ever known. Her two younger brothers were born here. Their lives will be different. They can get driver's licenses and financial aid for college.

Itzel Ortega works out the logistics of a video project with fellow architecture student Shimin Cao. "I don't want to be extraordinary, I just want to be normal," Ortega says. Her mentor, Leticia Arreola, preferred not to be photographed. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

As a high school freshman, Ortega had her heart set on a college prep program for low-income high school students.

Someone from the program called to say she was a strong candidate, but asked why she hadn't supplied her Social Security number on the application. She had no number. Other students would get the summer programs, the internships and the college campus tours.

Why take Advanced Placement classes, why join clubs, why be active at school if she would only hit more dead ends? She cried, then regrouped. She would keep studying hard, even if she didn't know how she would pay for college or get a job.

After graduating from South El Monte High, she attended community college, earning straight A's. Then she confronted the questions she would face eventually, when her ambitions clashed with the realities of her undocumented status.

Ortega's brother Guadalupe is a freshman at UCLA, a pre-med student on full scholarship. He lives on campus and rarely goes home. Ortega lives with her parents and commutes to school by bus, a two-hour journey. She should be an architect by now, but Cal Poly didn't accept her community college credits, so she had to start over, with a graduation date of spring 2014.

"My brother is Mexican American. The world handed us different cards. His cards are better. He's a real American," she said. "I don't feel like I can claim it. We're a border society, neither here nor there."

Last summer, President Obama unveiled a program for immigrants who came to the United States illegally at a young age. Those who qualify would receive work permits and a two-year reprieve from deportation.

With a cousin and two friends, Ortega lined up at 2 a.m. outside a local nonprofit for help with her application. The next appointment was not until November, so she assembled the paperwork herself, a stack 6 inches thick of school transcripts and utility bills stretching back to when she was a toddler — proof of a Southern California childhood.

Ortega's parents borrowed the $465 fee from friends. She would earn the money back by helping other families with the process. Then, her father won $1,000 in the lottery, a stroke of luck he used to buy two years of time for his daughter.

"I don't want to be extraordinary, I just want to be normal," Ortega said. "I want to do the normal things people do. The milestones — driving when you turn 16, moving into the dorms at 18 — I didn't get that."

In December, she presented a project at Walt Disney Studios. Her model had sliding panels to create rooms with echoing walls where visitors could speak, or shout, their minds. The theme was freedom of speech, the building was an embassy near the United Nations.

Itzel Ortega won an award for a project submitted in a competition for a Disney internship. Her theme was freedom of speech. (Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The Disney judges gave her a top award. She was a front-runner for a paid internship at the company. But as long as she was here illegally, she couldn't claim the job.

When she arrived home that night, an envelope from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services was waiting.

Inside was her future. She could work for Disney. She could be a normal college student. She could be free from fear.

She still needs Arreola's help. Under a new California law, she is getting some state aid — about one-fourth of her tuition, starting this quarter — but she still can't get federal grants or loans. A path to citizenship for the estimated 11 million people in this country without proper legal status is on the table in Washington. For now, Obama's deferred action program is all she has.

Arreola has kept her good deeds to herself. Her father died recently, unaware of her generosity; she told her mother only a few months ago.

Slaving over her Disney presentation, Ortega was too tired to celebrate.

The feeling was not joy — more like relief. It was no longer against the law to be home: "I think it just gives me peace," she said.

Follow @cindychangLA on Twitter

More great reads:

Given up for adoption, but not for lost

Timbuktu calligrapher keeps ancient learning alive

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.