Rich Paul’s love of vintage jerseys led to his first meeting with LeBron James

I liked to buy sneakers and put them on ice for months, just waiting for the perfect occasion and outfit. I had some black Bo Jacksons in the stash and wanted to pair them with a Latrell Sprewell Knicks jersey. You might wonder how those two things go together, but I didn’t like to coordinate colors that looked too matchy-matchy. I was more into complementary accents. I wanted the white Sprewell jersey because his number “8” was outlined in black and there were black accents down the side, which would pop when paired with the black sneakers. I would never wear the white, orange, and blue Bo Jacksons with the white, orange, and blue Knicks jersey. Anybody could do that.

Early in 2001, my friend Mike E and I went on a shopping trip to New York City, and of course we hit the NBA Store on Fifth Avenue in midtown. I found my Sprewell and was standing in the checkout line when some unfamiliar jerseys caught my eye. I knew the players and teams, but I hadn’t seen the uniform styles before because they were from the 1960s and ’70s. I saw a Bill Russell jersey from the Celtics, an Elgin Baylor from the Lakers, and an Oscar Robertson from when he played for the Bucks. The name ‘hardwood classics’ was on the labels.

I loved the feel and detail and thought the jerseys were dope, so I bought the Baylor and the Robertson for almost four hundred dollars apiece. I liked Russell’s Celtics jersey, but it felt a little too plain for me. I knew exactly what I was going to do with the others. I had a pair of Timberlands in mind to go with the Oscar Robertson. I wore the Elgin Baylor under a navy blue Polo leather coat that I bought from the Polo store in Philadelphia.

Back home, when I wore those jerseys to the club, the response was off the chain. Everybody kept saying, “Where’d you get that? I need me one of those!” This is before you could easily buy clothes on the internet, and you had to show up to a real-life store to buy anything.

I had a little makeshift office in my house with a computer. I went online, typed in a search for “Hardwood Classics,” and a store in Atlanta called Distant Replays popped up. I called the store and the owner, Andy Hyman, answered the phone.

I talked to Andy about what jerseys he had in stock and got excited when he mentioned all the football and baseball joints that were not on his website: Tony Gwynn with the Padres, Pete Rose with the Reds, Randall Cunningham with the Eagles, even some names I had never heard of despite considering myself a sports historian from watching all those games as a kid. I bought three jerseys during that first phone call, for about a thousand dollars total, including overnight shipping. I spent another thousand dollars the next week, and another thousand the week after that. I did that for about eight weeks straight. Everybody in Cleveland was Polo’d out, so when I started showing up in Jim Browns and Hank Aarons, it caused a major sensation. I wore each jersey once — they were one and done — and then stacked them in my closet.

After about two months of this, I called Andy and said, “I’d like to invest in your business.”

“Really?” he said. “If you’re serious, come on down to Atlanta and we’ll talk.”

Andy was a cool dude, a middle-aged white entrepreneur who started Distant Replays in a kiosk at the Greenbriar Mall. Andy is the one who sold OutKast their jerseys when they wore the rainbow Astros and the Falcons’ Steve Bartkowski in videos and photo shoots. We talked and Andy told me that he couldn’t let me invest, but if I worked in his store one weekend each month, he’d give me 40 percent off all my purchases. I agreed and shook hands before he could change his mind. Andy could have offered me 10 percent off and it would have been a good deal for me. I started flying down to Atlanta once a month, staying at a Marriott Residence Inn up the street from Distant Replays.

I’d been working in my dad’s corner store my whole life, so working for Andy was a layup. I ran the credit card machine, worked the register, and dealt with customers on the floor. The store sold all kinds of sports apparel in addition to jerseys — this was the South, before hip-hop fashion went fully mainstream, so you might have a white father and son who didn’t look cool in jerseys but wanted T-shirts and hats. Andy showed me how much of a market there was for all this other sports stuff. And at the end of each weekend, I had the pick of the litter with jerseys. They cost three hundred in the store; Andy sold them to me for one-sixty. I flew home with around twenty to thirty jerseys and sold them for the price on the tag: three hundred, sometimes four hundred or four-fifty. They moved right out the trunk of my Toyota Camry.

Man, those jerseys sold better than crack. A big part of their value came from the fact that I was the one selling them. My reputation connected to the product made it fly. People said, “Why should I go to the mall, and maybe pay a higher price, when I can get it from Rich?” Plus I advised people on what to buy. I put a lot of my old sports knowledge to use, bringing back facts from all those late-night games I watched alone as a kid or on the floor of Grandma Johnnie Mae’s house. I also explained to customers how the authentic jerseys with sewn-on letters and numbers were of much higher quality, durability, and historical significance than the replica jerseys with iron-on letters and numbers. I’d pull up to the park or the dice game and boom — five jerseys would sell just like that. I met the Cleveland Browns fullback Corey Fuller at a dice game, and when he saw what I was wearing he told me to pull up to his house out in Westlake. He bought two or three jerseys. CC Sabathia, in his early years with the Indians, bought some. I had all those guys. It got to the point where get word out that I’d be in a random parking lot and the customers would come right to me. Moving jerseys out of the trunk of my car wasn’t nearly as dangerous as moving drugs — and it didn’t tug at my conscience. It made me feel free.

“Out the trunk” is a mentality that still fuels me to this day, and it comes from more than just selling jerseys. It’s about chasing down every little opportunity, putting in extra effort, and doing whatever it takes to improve your position. Phil Knight started out the trunk with Nike, carrying boxes of sneakers and racks of clothes around. “Out the trunk” forces you to interact with people, to develop communication skills, to understand the value of time. All my hustles brought me into direct contact with people — I call that kind of personal touch in business hand-to-

Hand combat. There’s something special in hand-to- hand combat that teaches you a whole set of skills you can’t quantify on a test. I learned much more coming up out the trunk than if I’d been born with a billionaire grandfather.

Andy was amazed by the volume I was moving, so he asked to come up to Cleveland and see for himself. The day before he arrived, I went to every block and told my people, “If you see me roll up with a white dude, he’s not the police, he’s my business partner — just buy whatever I got.” We drove all over the hood, jerseys flying out the trunk, and Andy was blown away. After that, I was buying so much product, Andy had to put me on to his connect — Peter Capolino, who founded Mitchell & Ness in Philadelphia. That was the company that had the NBA license, manufactured the jerseys, and sold them to Andy.

In the spring of 2001, I had just bought a pair of Adidas from a store called Walton’s, white low-tops with three red-suede stripes and a strap over the top of the ankle. In my mind, I put them together with a sky-blue Warren Moon Houston Oilers throwback, because Moon’s number “1” had a red outline around it. I had a trip to Atlanta coming up, and the day of the flight I assembled that combination and headed for the airport.

My man D Hodge booked the tickets. For some reason, he scheduled the flight out of the Akron airport instead of Cleveland. OK, cool.

I was waiting to board the plane when a few tall young dudes walked up to me. The kid in the front wore a Mike Vick jersey, from the Falcons, but it was a replica with a big ironed-on “7” on the front. “What kind of jersey is that?” the kid in the Vick asked me.

“This is an authentic Warren Moon jersey, from the Oilers. I got a whole bunch like these if you want, I’m available 24/7/365 for the most part. Here’s my card, just ask for Rich, you won’t have no problems. So what’s your name?”

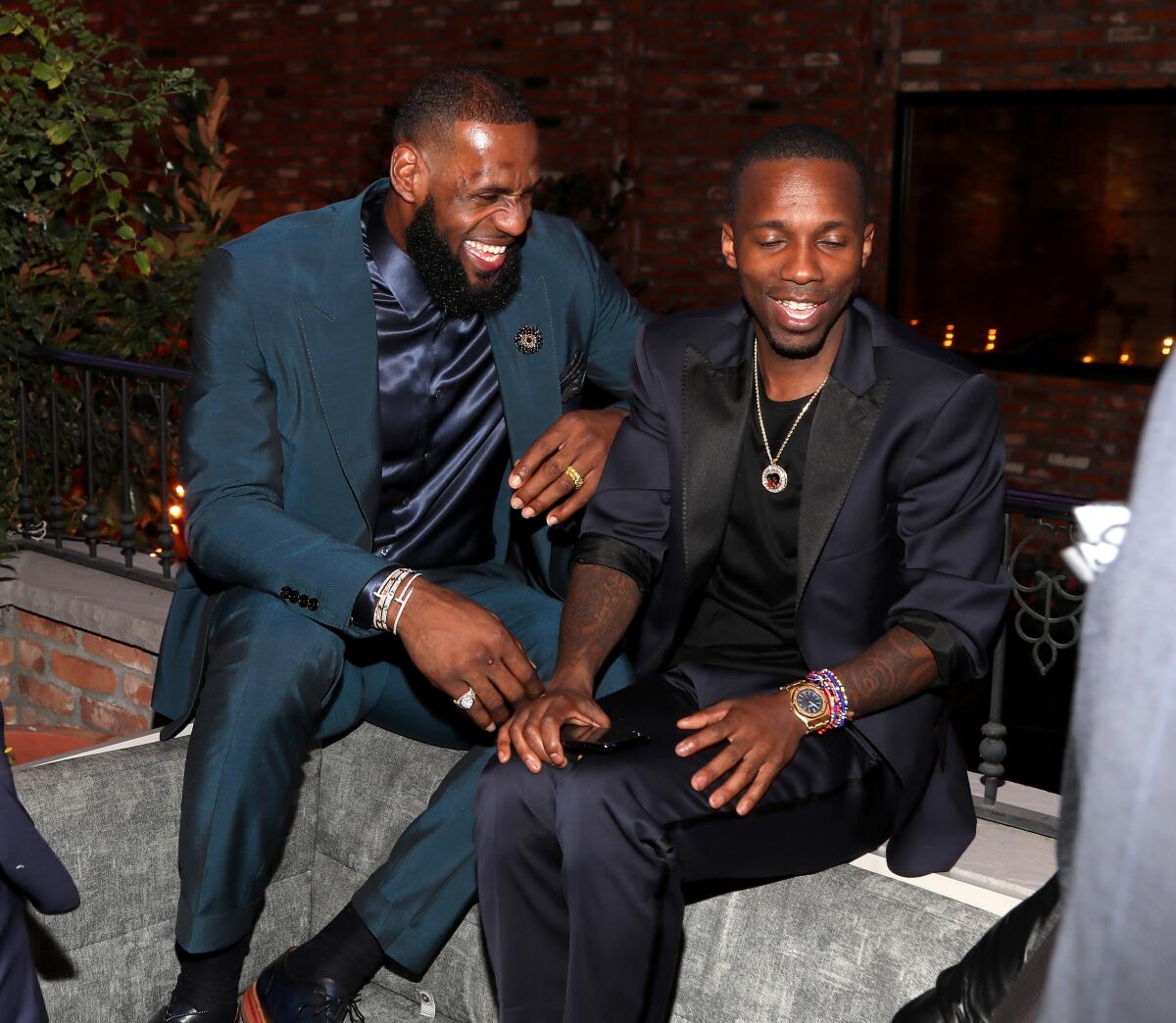

I stuck my hand out. He gave me a pound. “What up, Rich,” he said. “I’m LeBron.”

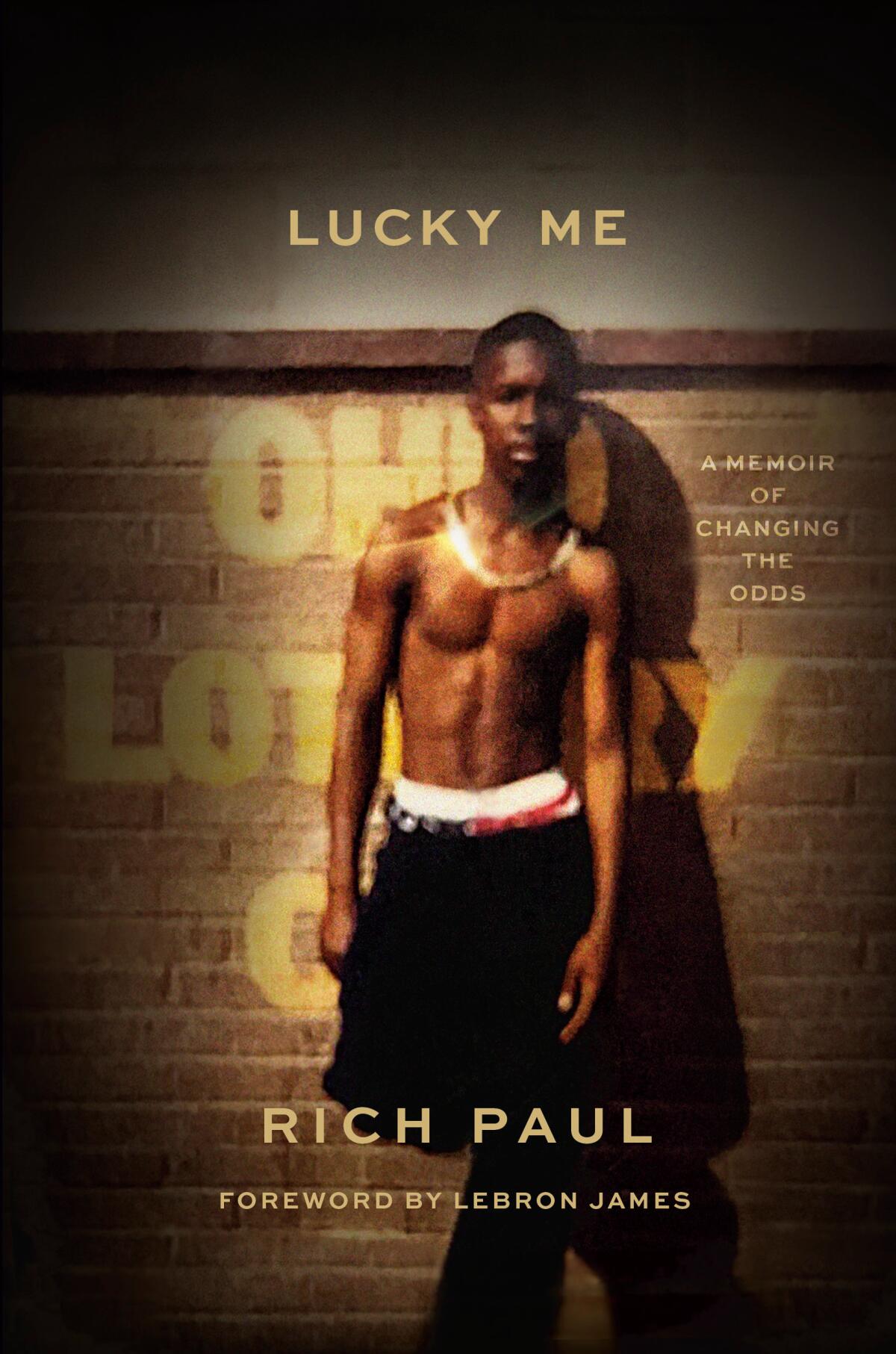

Excerpted from Lucky Me by Rich Paul with Jesse Washington. Copyright © 2023 by Rich Paul. Excerpted by permission of Roc Lit 101. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.