Excerpt: The NBA Finals night Jerry West went for 53 and the Logo was born ... maybe

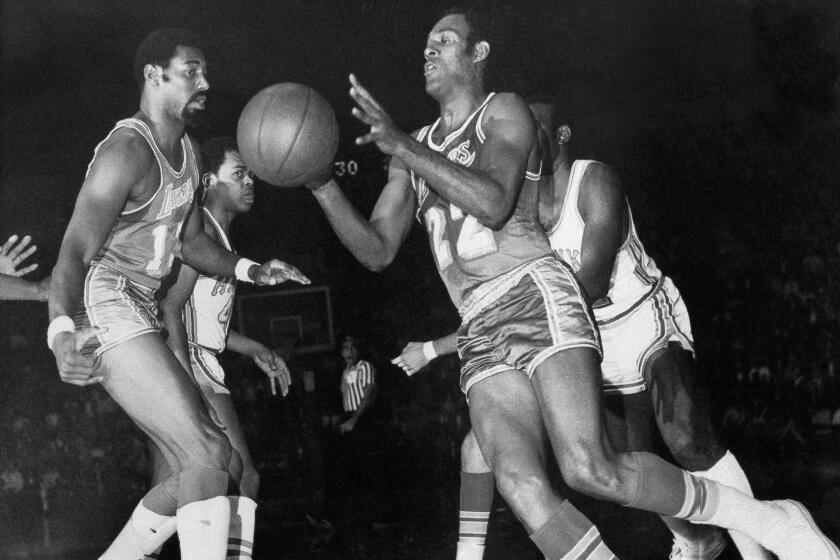

In the spring of 1969, an aging Boston Celtics team, led by player-coach Bill Russell, was vying for its 11th NBA title in 13 years. Five of those banners came at the expense of Jerry West and the Lakers, who had yet to win a championship since moving to L.A. in 1960. Something felt different about this series. There was the addition of Wilt Chamberlain, for one. And there was West himself.

There are other nights when the basketball will be a feather with a steel tip at the end, a dart, flying off the hand with purpose and direction, control and beauty, nights of basketball magic and basketball wonder. This — April 23, 1969, Los Angeles , CA — was a night of basketball magic and basketball wonder.

The Lakers’ 120-118 win in the first game of the 1969 NBA finals could have been framed and preserved, hung in a gallery under a professionally lettered sign that read “THIS IS HOW BASKETBALL SHOULD BE PLAYED.” Players flew up and down the regulation court at the Forum, 94 hardwood feet long, 50 feet wide, made shots they were supposed to make, dunked on each other, blocked each other’s easiest paths, played the game with high-fidelity grace and style.

The lead changed hands 27 times. The game was tied 14 times. The Lakers had an even 100 shots. The Celtics had 100 shots. Five players on each team scored in double figures. Jerry West scored 53 of those points, 53 beautiful backcourt points.

The Lakers were ahead by a point after the first quarter, the Celtics ahead by two at the half, a lead they maintained after three quarters. The Lakers won the game with 38 points in a dramatic fourth quarter, the Celts with 34.

Whew.

The losers still were clawing at the end as Sam Jones hit a bank-shot jumper to cut the margin to a point with a second left. On the in-bounds pass, they then whacked Elgin Baylor, whose foul shot created the final score. This was a photo finish. The hometown team was ahead by a nose at the end. That was what the picture would show forever.

“We were fortunate to win a game like that,” Jerry West said. “As a sports fan, I wish I could have been a spectator for that one.”

On the way to the finals, both the San Francisco Warriors and the Atlanta Hawks had double-teamed him the entire way on defense, an attempt to keep him under control while forcing other Lakers to do more on offense than normal. The Celtics’ approach was to play straight-up man-to-man, one-on-one, an attempt to shut everyone down, not just the best scorer. This gave West free air, room to maneuver. He went over and around Emmette Bryant, Larry Siegfried and Don Chaney. Half his shots seemed to go through the steel rim with 4½ inches to spare on all sides.

Elgin Baylor never received the level of adulation from Lakers fans that other team legends received. He was a pioneer in a town with a short memory, Bill Plaschke writes.

“I’ve never seen West play better,” the Celtics’ John Havlicek said. “Don’t forget he had 10 assists. He accounted for 73 points tonight.”

The Lakers star said the addition of Wilt Chamberlain, who had forced a trade from Philadelphia the previous offseason, made his life much easier. Time after time, the Lakers would isolate West one-on-one with whatever troubled soul was guarding him. Then they would watch him go to work. He would beat his man, slice to the basket for a lay-up, unimpeded by the familiar shot-blocking presence of Bill Russell.

“I’ve never seen West play better. Don’t forget he had 10 assists. He accounted for 73 points tonight.”

— The Celtics’ John Havlicek

“Wilt freezes him,” West said of Russell. “He can’t contest me that much on drives because of Wilt. He can’t afford to leave Wilt to come after me. What I try to do is look for him first on a drive. If I don’t see him, I just forget about him.”

The Lakers had never won the first game in playoff series against the Celtics. (They also never had played a first playoff game against the Celtics at home.) This fact was an instant injection of confidence. Old patterns might be changed. The Celtics at the same time were happy that they were a far different team than the one that was blown out by the Lakers, 108-73, the last time the teams met at the Boston Garden. They had given West his 53 points in this one, the most he ever scored in a playoff game, and lost by a basket. Was he going to score 53 points every night? Probably not. Definitely not. That brought confidence right there.

‘It’s a miracle’: Bucks assistant coach Vin Baker was a $100-million NBA star before addiction destroyed his career. How he reclaimed his life.

What was one loss in the first game of the playoffs?

“You’re never out of a playoffs unless you’ve lost four games,” Havlicek said.

What was one win?

“The way I look at, we got the breaks at the end,” Wilt Chamberlain said. “Was this a psychological win? Let’s say we’re one up with three to play.”

The winner really was everyone. In a golf match, there is always the debate about whether a person is playing against his opponent or against the course. In basketball, the game almost always is against the opponent, but tonight it was against the course. And the humans won.

“A game is a game is a game,” Red Auerbach said in the Celtics locker room.

(Pause)

“Didn’t Gertrude Stein say that?

::

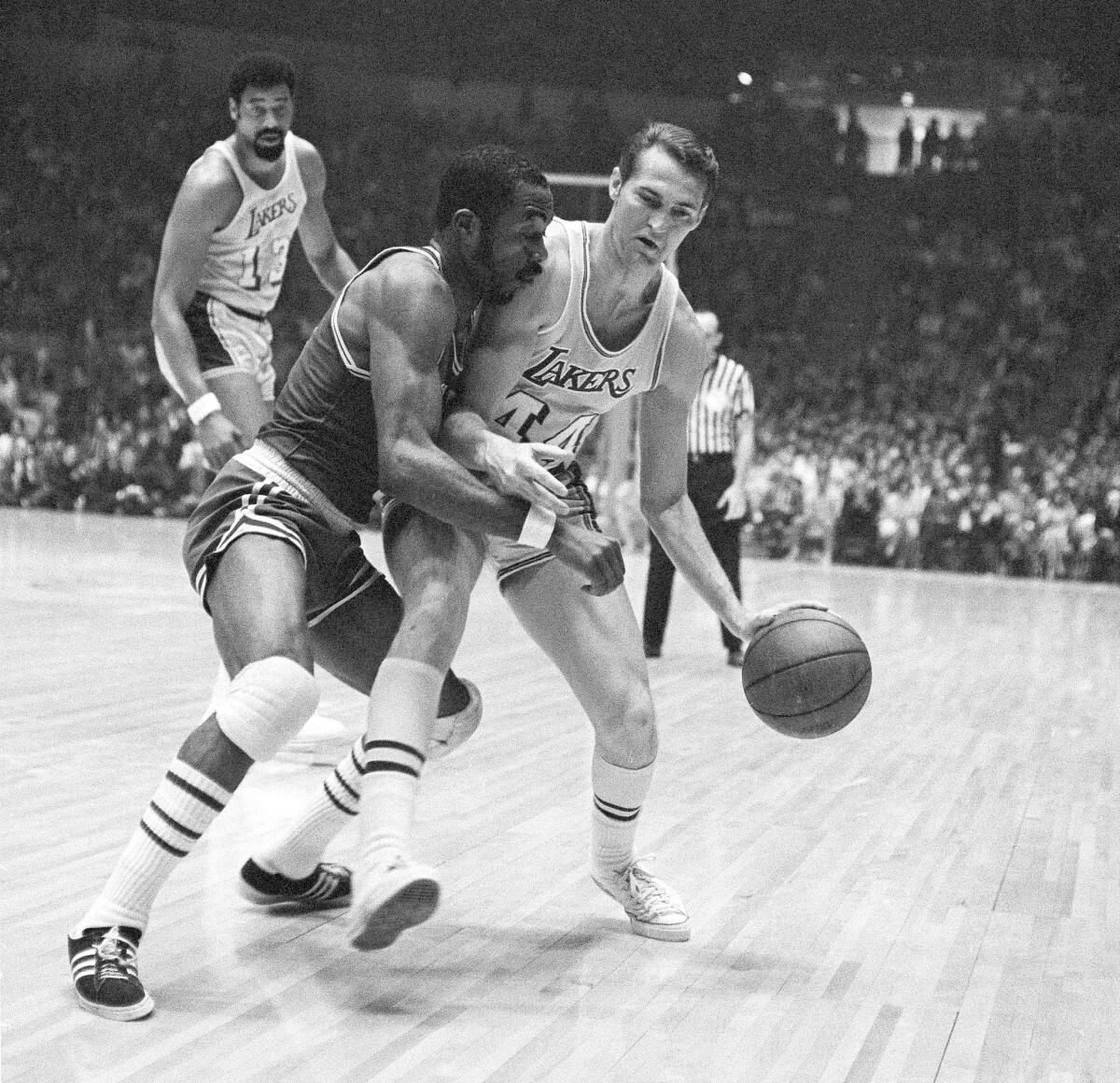

One reminder from the night was that West still was the leading man in this production. Win or lose, the spotlight would shine first on him. That fact had been overlooked in the build-up for the clash between Russell and Chamberlain. The newness of that storyline — these two highest-paid pituitary wonders, these basketball giants, meeting in a new circumstance — had created a science-fiction, monster-movie excitement. Forgotten was the baseline drama, the art-film tale of the local hero’s quest to yank Excalibur from that stone, to beat the Celtics in a seven-game series, fair and square.

West was the long-suffering local heartthrob, thin and stylish and precise, good-looking, efficient, humble and proud, a Maserati of a man, perfect for star-conscious Los Angeles. Thirty years old, finishing his ninth season, first player drafted when the Lakers moved west from Minneapolis in 1960, he had become the face of the team. He had accumulated a bunch of Chick Hearn nicknames, that included “Zeke From Cabin Creek,” a tribute to his West Virginia roots, and “Mr. Outside,” to go along with Baylor’s “Mr. Inside,” but the one that stuck the most was “Mr. Clutch.” He would take the tough shot. He would make the tough pass, grab the tough rebound, guard the tough scorer, win the tough game.

Except when he didn’t.

The five losses in five finals to the Celtics were ink blots on his resume, a scattering of failures that blemished his career. The losses weren’t entirely his fault of course — he still was Mr. Clutch to all of Los Angeles — but they brought great sadness to everyone involved. Every season was wonderful until the end. Frustration had followed frustration to create a discouraging pile. No matter how good things ever became in the winter, eyes always searched the sky for trouble in the spring.

“The same old story, Boston,” West would say about the finish a year earlier, the 1968 loss in six games, in “Mr. Clutch: The Jerry West Story,” his first autobiography, written with Bill Libby. “I had been in the league eight seasons. We had reached the finals and lost to Boston five times. We walked down to our dressing room, which was closed to the writers and outsiders for a while. We sat there sweaty and sore and sick of losing for a long time.”

“The Lakers didn’t draft him, they found him under a rainbow. “

— The LA Times’ Jim Murray on Jerry West

What would it take to win this thing? How good would it feel?

He could only guess.

“I sat there remembering twice in the game when the ball was on the floor and Siegfried dove for it,” West would write. “He didn’t just go for it hard — he dove for it. And they’re all that way on the Celtics. You can’t teach it. Everyone wants to win. It’s more fun and pays better. But the willingness to do anything you have to do to win, the willingness to spill your guts, the willingness to sacrifice yourself — this you can’t teach and you can’t talk into a man.”

He had acquired a West Coast sophistication, this shy character from Cheylan, W.V., a town whose post office was located in Cabin Creek. He had been a lonely little kid, youngest of six in a big family, a kid who shot baskets by himself, day after day, expecting nothing until, God almighty, he grew six inches between ninth and 10th grade and became a high school star. The rest had been a wonder. Four years at the state university, where he set all the records and was a letter-sweater god. Drafted by the Lakers at No. 2 after the Cincinnati Royals picked Oscar Robertson first.

He was everything the good folk of Los Angeles wanted, a basketball version of Sandy Koufax, Cary Grant in sneakers, almost elegant in the way he played the game. His white skin didn’t hurt his popularity, but wasn’t the basis for it, either. His ability was undeniable. He was the point guard every kid wanted to be. He was quick and steady, able to make the proper decisions, shoot or pass, stop or drive, at pell-mell speed, surrounded by trouble. His jump shot came out of a textbook. He was, yes, Mr. Clutch.

“The first time you see Jerry West, you’re tempted to ask him how things are in Gloccamorra,” Jim Murray of The Times wrote, trying to describe the beauties of the local man. “The Lakers didn’t draft him, they found him under a rainbow. Either that or they left a trail of bread crumbs in the forest and they snapped the cage when he showed up….

“Inch for inch, he’s the greatest player in the world. There is no more exciting sight than Jerry West dervish-ing down the court with a basketball, eyes and nostrils flaring, basketball thumping. His shots are a blur.”

His disposition seemed as steady as game. He was the easiest of interviews. Win or lose, he told reporters how he felt. He had an Eagle Scout sort of honesty, hard to find in any setting, particularly hard in a professional sports locker room filled with egos and agendas. Ask him a question, he would provide an answer that came straight from inside his thoughts. No filters were involved. He told you what he felt.

“Is this the best game you’ve ever played in the playoffs?” he was asked on this night. “It’s the most points you’ve ever scored.”

“Scoring’s not that big of a thing,” he said, staying in perfect character. “The big thing is that we won and I just happened to score a lot. I’ve had nights where I only scored 15 or 16 points and I’ve thought I played better all-around than this.”

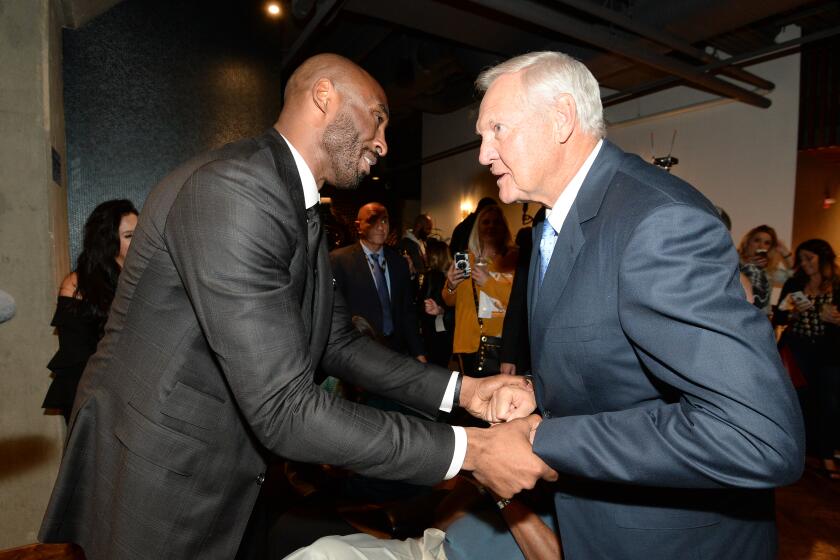

At 82, Jerry West doesn’t try to hide the cracks in a fabled life. “I wish I would have done something really important in my life.”

His crusade to win a championship had become an entire city’s crusade. He was too good not to win one. Even the Celtics said they felt bad for him when they beat him yet again in the finals the previous spring. Havlicek came to the Lakers’ locker room to commiserate. Russell came. Even Auerbach admitted he felt sad — a little bit sad — for Jerry West every time. Now the quest had begun again. Mr. Clutch was three games from making everyone happy. Even, in a weird way, his opponents.

“If we don’t beat the Celtics this time,” West said in his Eagle Scout honesty, “it will be a crime for the game of basketball.”

::

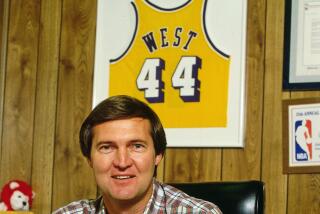

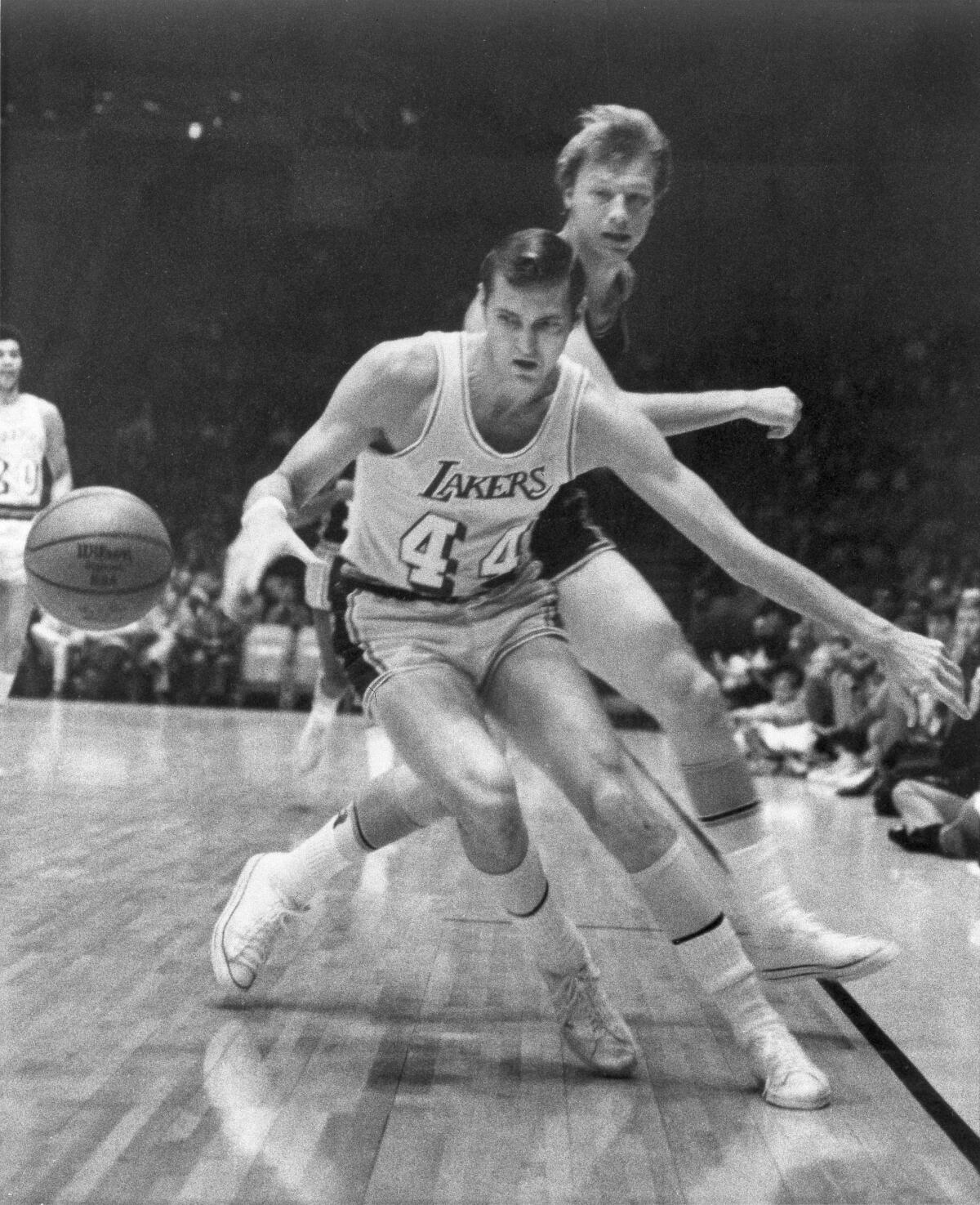

At the end of the 1969 season, somewhere during the summer, NBA commissioner Walter Kennedy would decide the league needed a new logo. The old logo was a plain basketball, dull and unimaginative, with the letters “NBA” printed on the front. Kennedy wanted something with more zip, modern, maybe with a touch of red-white-and-blue patriotism on the side. Something like the logo that Major League Baseball introduced at the start of the 1969 season for its 100th anniversary, the white silhouette of a batter ready to hit a baseball against a blue and red background.

Alan Siegel, a young designer in New York who had overseen the MLB project, had started his own company. Kennedy contacted him. Siegel went to the offices of Sport magazine where he looked at a file of basketball photos. He picked out one of West that was taken by Lakers team photographer Wen Roberts. West was leaning to his right in the photo, but dribbling with his left hand. The photo had balance, symmetry, action. Siegel created a white silhouette of West’s figure, added half a background of blue, top to bottom, on the left side, then red on the other half. He added “NBA” in white at the bottom.

“I did the project in 20 to 40 minutes,” he said.

Kennedy approved the design. There were no focus groups, no company meetings. (The NBA office had six people, including the commissioner.) West would be the figure in the NBA logo for the start of the next season until . . . well, present day.

There never would be mention of when the picture was taken. (There never would be official recognition, either, that West was the inspiration for the floor-based dribbler in short pants, though everyone who knew basketball knew it was him.) The picture cited most often, though, a perfect match, shows him dribbling at the Forum, gold home uniform, everything the same as the silhouette.

The idea here is that it was taken on April 23, 1969.

Why not?

This was his logo-perfect night.

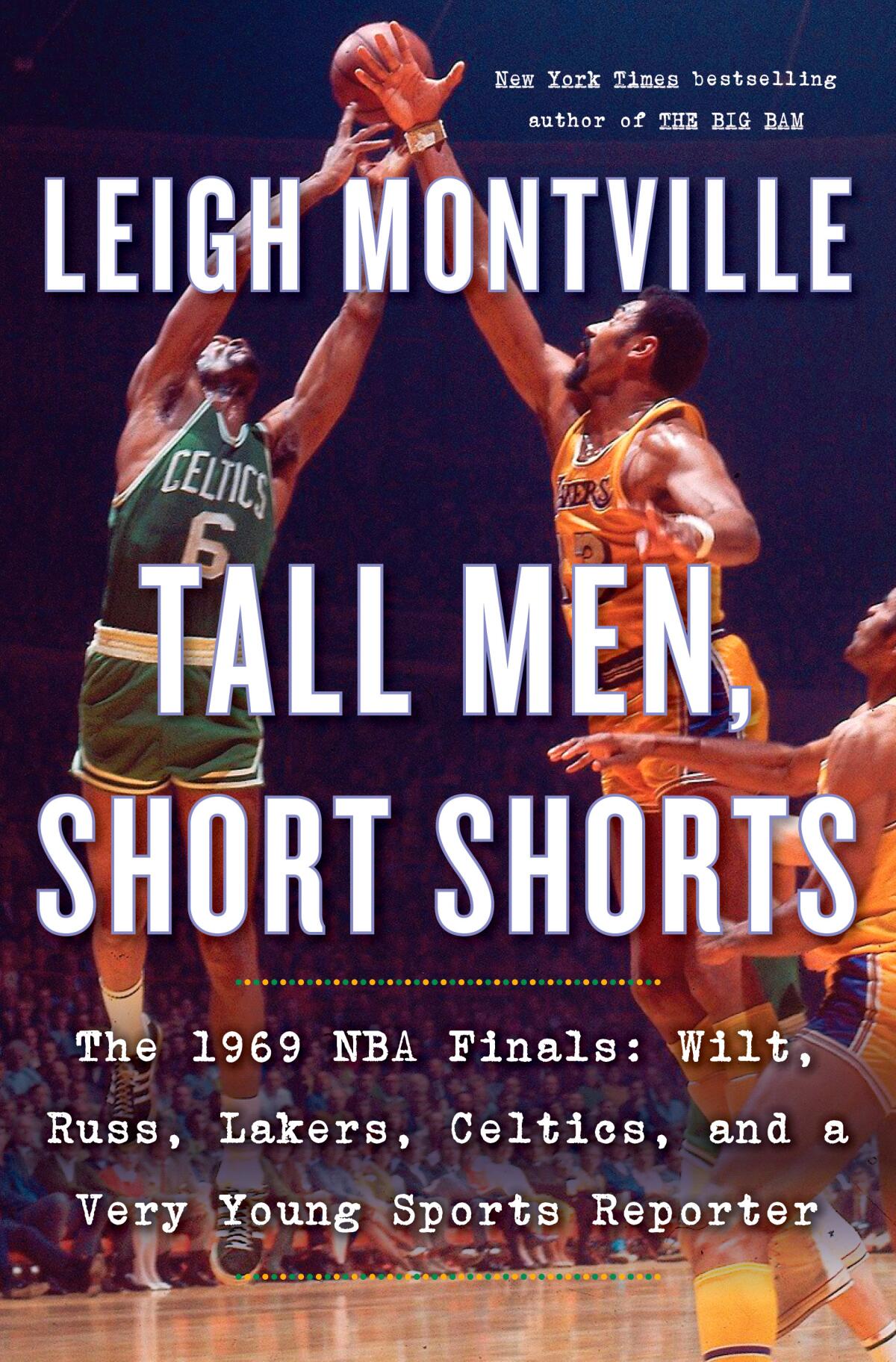

This article has been adapted from “Tall Men, Short Shorts” by Leigh Montville. Copyright © 2021 by Leigh Montville. Published by arrangement with Doubleday, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. You can purchase the book here

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.