Vin Baker sat outside a fancy Phoenix resort in the early morning sun, the mercury hitting triple digits before 9 a.m. His glass of Diet Coke wasn’t the only thing sweating.

The team he helps coach, the Milwaukee Bucks, had just lost the first game of the NBA Finals, and the competitive fire that burns inside won’t let him fully shake that. But it’s a new day, a new morning, a new opportunity.

He talks about the game the night before. He talks about his life. His wears a bracelet on his right wrist that reminds him “It’s OK to not be OK.” The NBA Finals are a good time for that perspective.

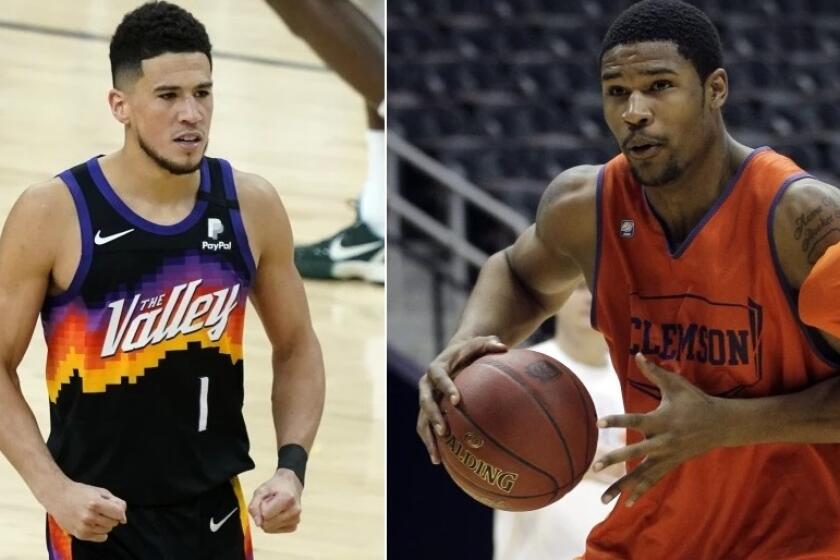

Earlier in the week, Suns star Devin Booker said that in the playoffs, when you win, it feels like you’ll never lose again. And when you lose, you feel like you’ll never win again.

Luckily for the Bucks, who a day later would lose again to fall two games down, comebacks are Vin Baker’s specialty.

It’s been 10 years since Baker had a drink, a sickness that cost him an All-Star NBA career, put immeasurable strain on his family and depleted more than $100 million in wages and endorsement money.

“There was a point where it was just waiting for the train to crash.”

— Vin Baker on his alcoholism and depression

It put pounds on his once-svelte body while stripping it of its athleticism and strength. It fed his anxiety. The chain reaction of events — the pregame weed sessions, the addictions to pills, the Bacardi and the Hennessy and the Courvoisier — it stripped him of everything, including his reputation.

There was nothing left for alcohol to claim. Except one thing.

“There was a point where it was just waiting for the train to crash,” Baker told The Times. “You know how that goes. Like people get into situations like mine where they lose this and they lose that. The next natural story is, ‘Vin Baker, boom. Something’s happened.’

Why is Devin Booker rooting against Devin Booker? Because he’s a huge fan of the Bucks’ star swingman. Make sense? Read on.

“That’s kind of how that should’ve been.”

Instead, it’s back to work.

::

Before he lost nearly everything, Vin Baker was held up as a totem of all that was right with basketball.

He is a preacher’s son from a small shoreline Connecticut town who was formally introduced to the basketball world in a 1992 Sports Illustrated profile titled “America’s Best Kept Secret.” In the accompanying photo, Baker is flashing a huge smile in his red University of Hartford uniform while students surround him with fingers pressed to their pursed lips.

He’d never had a drink before he got to college. He was terrified of drugs, especially cocaine, because of the overdose death of Len Bias in 1986. The Bucks took Baker eighth in the 1993 draft, and by his second year he was an All-Star.

Baker was nearly 7 feet tall but gifted with more than a big man’s skills. Think Anthony Davis squaring up from 20 feet on one end, then rejecting a shot at the rim on the other.

That was Vin Baker.

The Seattle SuperSonics traded one of their franchise icons, Shawn Kemp, to get Baker and in his first year with his new team, they won 61 games (only Chicago and Utah won more). Baker began to shed the “good player, bad team” label that he acquired in Milwaukee.

“I’d never felt so important and invincible in the sport of basketball in my life. So along with that, my first thought was, I guess the next progression is I can party and hang out like I want to. It’s the spoils,” he said. “I’m an All-Star now in another conference on the best team in basketball. And this is during the Jordan era.

“It was like, I made it. Along with that came the celebration. And I celebrated and celebrated and celebrated almost every day.”

The mounting pressure that came with success made Baker highly sensitive to criticism. Holding himself to the standards of players such as Michael Jordan, who hand-picked Baker to be an early endorser of his sneaker brand, was hard enough. Doing it while slowly entering a cycle of alcoholism made it impossible.

“America’s Best Kept Secret” soon would be exhausted by trying to keep one of his own.

A playoff appearance in his first year in Seattle ended with a second-round loss to the Lakers, a disappointment after such a promising season.

“I know all eyes are on me,” Baker said. “And I kid you not, that terrified me. Like, everyone’s watching now.”

Even before Rachel Nichols’ comments about Maria Taylor surfaced, ESPN had failed its journalists of color by failing to invest in the leadership needed to address such a situation.

His grip on everything began to loosen, and still, he was a member of Team USA in 2000.

But as his play began to suffer, the signs of a serious problem became easier to spot. Teammates could smell the alcohol coming out of his pores at practice. During games, he would drink Bacardi Limón from a water bottle in the locker room.

A trade to the Boston Celtics, a return close to his childhood home, did little to address Baker’s problems. Soon, he publicly addressed his problems.

“I’m an alcoholic,” he said before the 2003 season.

Within six months, Baker had graduated to drinking Listerine — which is 54-proof, more than most beer and wine — to satisfy his addiction. He lost nearly $1 million in one night in Las Vegas. He was given additional chances after the Celtics released him — a stint in New York, one in Houston, a brief stop with the Clippers. He scored only 863 points after leaving Seattle, hundreds fewer than he had in his rookie season alone.

Soon he was out of the NBA, bad investments further draining his bank account. He was arrested for driving under the influence. He lost homes. He stopped smoking weed and kicked the pills, but soon, he was back to drinking Bacardi 151.

“The rock bottom for me wasn’t necessarily knowing and understanding that I couldn’t get back in the league. It was more than that,” Baker said. “And I mean this wholeheartedly. I knew I felt abandoned by God.”

His money was gone. His job was gone. His fame had been replaced with shame. His family had grown frustrated. He felt like Job with a broken jumper.

And it left Baker, reduced to living in his childhood home, staring into the mirror at what used to be one of the best basketball players in the world.

He prayed for help. He called his father, the preacher, and told him he wanted to get some. And, this time, his fifth trip to rehab, it worked.

“I was so ready to change and I had nothing,” Baker said. ”Ironically, like when all the conditions were taken off — contract, career, save this, save that, save this … I had nothing to save other than my life.”

::

The Bucks are in the NBA Finals, trying to find their footing in their first trip to basketball’s biggest stage since the days of Lew Alcindor and Oscar Robertson. In between questions about his injured knee and time-consuming free-throw routine, Giannis Antetokounmpo calls Baker a “great friend.”

“He’s just a great human being,” the two-time most valuable player said.

After losing two games to the Lakers in the first round, the Phoenix Suns discovered the depth of their capabilities in their trek to the NBA Finals.

Everyone around the Bucks has a Vin Baker story, some moment when he did something or said something to make someone else feel good. Conversations with him don’t end in handshakes; they end in hugs.

During the breakfast in Phoenix the morning after the Game 1 loss, Bucks co-owner Marc Lasry joins Baker for a few minutes to pick his brain about what happened the night before. Later, he’ll say that Baker has a “heart of gold.”

“His outlook on life is just … every time I’m around Vin Baker, I want more,” Bucks coach Mike Budenholzer said. “And he’s good for me. He’s good for our players. Yeah, it’s hard to kind of describe unless you get to experience Vin on a day-to-day basis, but he’s very special, very good. His perspective — the words, the thought behind it — yeah, he’s really good for the players, really good for all of us.”

The path to sobriety for the former All-Star began with reconnecting with his faith. In addition to working with Alcoholics Anonymous, Baker attended services at least four times a week. He told his father he wanted to share a story.

While his soul started to heal, he was still broke. He called one of the owners he used to play for: Howard Schultz of the SuperSonics. Schultz set up an opportunity for Baker to work at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. He made money on some trips overseas to play in exhibition games. He went to North Korea with Dennis Rodman.

But salvation came in an even stranger place: inside a Connecticut Starbucks as one of the chain’s tallest baristas.

Baker became a management trainee and eventually had his own store, waking up to open the shop around the same time he used to be stumbling home.

“It’s a miracle how the story has turned around,” Baker said.

He had a chance to work for the Bucks under former coach Jason Kidd, but the lack of a guaranteed contract put his return to the NBA on pause. He began working on Bucks TV broadcasts in 2016. He worked with big men around the league before getting a full-time coaching spot with the Bucks in 2018. He stayed with the organization when Budenholzer took over before the 2018-19 season.

His bond with members of the organization is undeniable. He spent two months last offseason working with Antetokounmpo in his home country of Greece, and their relationship deepened.

“One night we were talking and we had never had this conversation. And Giannis said to me, we were at dinner, and he said ‘Coach, like, your story’s amazing. Like, I cannot believe it … it’s hard for me to even fathom what you’ve been through.’

“He was in awe that I had made it back from what I had gone through and I didn’t even realize he knew the extent of it.”

But Baker is determined that people know what he’s been through, what he’s experienced, because it can provide perspective. It can provide comfort. It can provide hope.

“This was an opportunity that was afforded to me not to screw up,” Baker said. “It’s not about me. Like, it’s not about ‘I made it. I’m a coach of the Bucks.’ It’s about there’s somebody watching. And I get a lot of calls to my foundation saying, ‘We saw you. Can you call us? Can you give my friend a call? Can you give my cousin a call? Can you call this business?’ I get a lot of those calls. And those to me are the most important calls that I can ever make.

“I understand the addiction from every single level. I haven’t left, in my mind, all the bad things that happened. Like, I didn’t forget about it. Nor have I forgotten about four years ago when I was just putting on a green apron at Starbucks. I’m not that far in the clouds. I have an absolute responsibility to provide hope for people who aren’t in healthy situations when it comes to addiction.

“That precedes anything else in my life.”

Last summer, he was a pivotal presence in the Bucks’ calls for social justice that brought the NBA postseason to a halt, bringing a spotlight to issues surrounding race and policing. And this year he formed “Vin Baker Recovery” to open treatment centers in Milwaukee.

“I call him my older brother,” Bucks forward Brook Lopez said. “It’s been a special bond that we have created. And he’s such a great basketball mind as well. Just having played on an NBA floor, he sees things sometimes the coaches miss. He knows what it’s like, and so it’s very special having him on the sideline.”

Baker’s past isn’t gone. His fight is ongoing. And the memories are everywhere.

But there’s peace in living a miracle, in knowing that the train never crashed.

Before Game 1 of the Finals, Baker was sitting next to the court when he saw Jeff Van Gundy, who briefly coached Baker in Houston during the dark final years of his career. Last week Baker approached Van Gundy to give him a hug, again thanking him for his support as he put his life back together.

Years earlier, when Baker had resurfaced in the NBA, he had seen Van Gundy at a game and sent over a handwritten note, thanking Van Gundy for his support while he was at his worst.

“I was a mess when I was there,” Baker remembered. “He wanted to give me an opportunity. I didn’t want it because I was an alcoholic.

“And now, here we are.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.