Column: ‘Pride Night’ would mean more if any of the athletes were open about being gay

Your clips are strong and you’re a good writer, but I can’t send a “faggot” in a locker room.

That’s what a sports editor said to me when I was first trying to break into sports journalism in the late 1990s.

I share this story whenever someone suggests things haven’t changed when it comes to the topic of gays in sports. I am living proof that things have changed. Jason Collins and Michael Sam and Robbie Rogers and Jake Bain and Scott Frantz are all proof that things have changed.

Yet, right now, there are no publicly out gay athletes competing in the four major professional men’s sports leagues — as was the case way back when that sports editor felt comfortable enough to direct an anti-gay slur at me during a job interview.

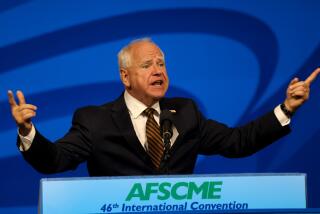

On Friday, LAFC hosts its second annual “Pride Night.” I had the honor of making the traditional release of Olly the falcon at the team’s inaugural celebration, and my ESPNLA 710 colleague Steve Mason gets the honor this year.

That the second-largest market in the country has two sports talk radio hosts who have come out as gay is another sign that things have changed. That a city as gay-friendly as Los Angeles has no male professional athlete who has come out is a sign that things haven’t changed enough.

“Professional athletes have such short careers, and, for players who aren’t elite superstars, careers are even shorter and more tenuous,” Mason said. “Athletes perceive that they will be risking everything by coming out. Not all sports fans are as accepting.”

Basketball player Collins in 2013 became the first major sport athlete to come out while still playing, but he was a role player near the end of his career.

“I understand the fear, but when the first real domino falls, when that first pro [star] makes this leap of faith, I believe that the reception will be better than they could have ever expected,” Mason said.

“I always expected some kind of tremendous backlash when I came out. There hasn’t been any. Twitter can be a very angry, hateful place and amazingly, since I have come out, I maybe got 10 to 12 hate tweets attacking me for being gay.”

Of course, there is a difference between being a sports personality and being an athlete. For example, Mason and I do not have to stand at home plate in front of tens of thousands of people and attempt to do our jobs while being called everything but a child of God. We also don’t have nearly as many teammates.

“When I came out, there was no discussion about this topic in baseball,” said Billy Bean, the former major leaguer who came out 20 years ago and has served as MLB’s first ambassador of inclusion for the past five. “When I returned to MLB in 2014, the conversation was new. So expectations were low and uncertainty about content was high.”

Since then, he added, “The biggest differences are that it has evolved from a concept to a priority. Leaders and ownership groups now fully embrace this subject as a priority, and part of our diversity conversation.”

The Dodgers are hosting their sixth annual Pride Night on May 31. The Galaxy are hosting their seventh June 2. The Clippers featured two same-sex couples on the Kiss Cam during the team’s annual celebration in January. The Kings featured five couples on Kiss Cam during their celebration in March.

The Lakers hosted their first Pride Night in September. The Angels are having their first June 25. (I’m participating on the panel that night as well.)

But when there’s not a single athlete who has come out on any of the teams, you have to wonder if all the hoopla is working.

“Pride Nights are not a replacement for our inclusive education initiatives, but they do convey a powerfully clear message about an organization’s values and desire to make every fan feel welcome,” Bean said. “Pride activations sponsored by our clubs are still relatively new and I have been pleased at how quickly they have been embraced across the league. Every year gets better and better.”

Neil Viserto, the Angels’ vice president of sales, helped organize the team’s Pride Night and said, “We believe having a discussion here at Angel Stadium is important and can be very effective. We want to be part of this effort to build awareness around inclusion and wanted to organize something that was effective and meaningful and not just simply check the box and have a Pride Night.”

But is it really more than a checked box if another calendar year goes by with no player who has come out as gay part of the competition?

Think about it: There is a gay man running for president, and no player who has come out as gay running the bases.

That means either none of the 750 active players on an MLB baseball roster is gay, or none feels comfortable enough to tell the public.

The odds say it’s the latter.

If it’s the former, then perhaps Bean is an outlier in the same way Glenn Burke, who played for the Dodgers from 1976-78, was an outlier. The way the NFL’s Dave Kopay, who played from 1964-72, was an outlier. The way Esera Tualo and Kwame Harris were. And Roy Simmons. And John Amaechi … Jason Collins … Ed Gallagher … Wade Davis.

If we’re being honest, it’s not that these major sports do not have gay players. It’s that there is still something within society that makes these men feel as if they can’t be as open about their personal lives as their heterosexual counterparts.

Some of that has to do with their own insecurities. A lot of it has to do with the conditions that foster those insecurities.

When I was asked to be the guest of honor for LAFC’s first Pride Night, it came on the heels of the team’s fans chanting anti-gay slurs during a match.

Slurs were still heard later in the season during the team’s first playoff match. Many people will say those and similar chants during games have nothing to do with gay people. Yet, there are no players who have come out as gay in the major four sports — despite the defeat of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” despite the legalization of same-sex marriage, despite gay and lesbian elected officials in large municipalities.

The reality is a heterosexual male can beat his spouse and still find a home in professional sports if he’s talented enough. But a gay male won’t reveal his spouse for fear he will be homeless in professional sports.

Maybe hosting Pride Nights will help change this dynamic. Clearly, that hasn’t happened yet.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.