Bean Active in Gay Rights

MIAMI BEACH, Fla. — The hotel ballroom is large and cold, the audience small, the topic hot: gay rights. The evening starts badly when a passer-by pauses at the doorway to shout, “This lifestyle is a sure ticket to hell.”

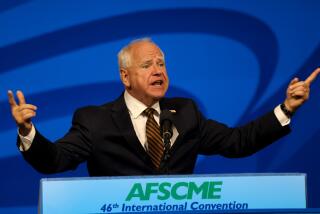

Billy Bean’s inner demons have told him worse, so he’s undeterred. He speaks without notes for 30 minutes, recounting the heartache and humiliation of hiding his sexual identity as a gay baseball player.

Bean tells how he deceived friends, family and the front office. He married and divorced, concealed a male lover for three seasons, witnessed his partner’s death and pretended it didn’t happen.

He believed he had to keep his secret to keep playing.

“In men’s sports there’s no choice,” says former Olympic swimmer Diana Nyad, a lesbian. “Billy is very poetic about telling you why that’s so.”

For the 37-year-old Bean to discuss his past with such poise and passion reflects a remarkable transformation. He struggled in misery to keep his personal life private while playing baseball, cut short his career in 1995 because of a gay relationship, and warily emerged from the closet two years ago.

Now he’s active in promoting gay rights, wants to be a role model and cheerfully notes: “I’m as out as you can be.”

A handful of famous athletes in individual sports have come out, including Nyad, Greg Louganis, Martina Navratilova and Billie Jean King. But few athletes in team sports have acknowledged being gay, even in retirement. The last well-known baseball player to do so before Bean was the late Glenn Burke in 1982.

Bean says friends from college and baseball took his disclosure well--better than he expected. And he began to see his experiences as something to share.

“I’ve learned making an impact on someone’s life is more important than a lifetime .300 batting average,” Bean says. “The more positive role models that people see, the less sensational the whole idea of diverse sexuality becomes.”

At the Millennium March in Washington last year, Bean spoke before a crowd estimated at up to half a million. The recent symposium in Miami Beach inspired a public employee to come out the next day. A young gay neurosurgeon on the West Coast saw an interview with Bean on television and was so moved he flew to Miami just to shake Bean’s hand.

Another fan is Elizabeth Birch, executive director of the Washington-based Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s largest gay political organization. Bean has made several appearances for the group.

“He has been an absolutely inspirational speaker, often to thousands of people,” Birch says. “We have come a long way in corporate America and within thousands of families, but baseball to many was deemed untouchable. Billy Bean has opened up that conversation.”

Bean was the quarterback, point guard and valedictorian at his California high school. He earned a degree and All-American honors in baseball at Loyola Marymount, then accepted a $12,500 offer to play professionally.

Today he’s a successful businessman--funny, friendly and happy. He lives with his partner of five years, sells and renovates upscale residential real estate, runs marathons and dominates his Sunday morning pickup basketball game.

“I’m proud I’m living honestly and openly,” he says during an interview over lunch in South Beach.

Idealistic but also realistic, Bean dreams of the day when a prominent active male athlete in a team sport acknowledges being gay. But he says a young player would be unwise to do so.

“There’s so much money involved, you’d have to be foolish or very rich to put your career in jeopardy,” he says.

Baseball is especially problematic, with few players educated beyond high school and a long tradition of macho clubhouse conservatism. A ballplayer who disclosed his homosexuality would face a more daunting challenge than Jackie Robinson, Bean argues, partly because media scrutiny today is so much more intense.

“It would become a circus,” he says. “I’ve never met the person that I think could do it.”

As a major league outfielder, Bean lacked the power and speed to become more than a fringe player. He shuttled between the majors and minors from 1987 to 1995, playing 272 games for Detroit, Los Angeles and San Diego and batting .226.

Domestic life was similarly unsettled. His three-year marriage broke up in 1992, the year he had his first homosexual experience. Raised Catholic in conservative Orange County, Calif., Bean long resisted the notion he was gay.

“I never even said the word to myself until I was 28. I used to pray it would go away,” Bean says. “I could have been a very good major league player if I was not so emotionally screwed up.”

Along with feelings of inadequacy, guilt and self-loathing, Bean was afraid he would be found out.

“I remember walking in the clubhouse every day and feeling people could see the kiss I gave my lover when I walked out the door,” he says.

Bean doesn’t know whether any teammates were gay. It didn’t matter; he didn’t dare risk a relationship with one of them.

Among his worst memories is the night of his first major league homer. That was in 1993, when he played for San Diego and lived with his partner, Sam, 25 miles from the ballpark to reduce the risk of unexpected visitors.

He and Sam were home that night when there was a knock at the door. Teammates had stopped by to help Bean celebrate. Sam slipped out the back and waited in his car for three hours until the teammates left.

“On what should have been the happiest day of my life,” Bean says, “I found myself the most disgusted and ashamed I had ever been.”

Sam died of a ruptured pancreas one morning in 1995. Bean went from the emergency room to the ballpark and played a game that afternoon because he couldn’t tell anyone about his partner’s death. After the game he was demoted to Triple-A Las Vegas, which forced him to miss the funeral.

“I expected bad things to happen to me because I felt bad about myself,” he says.

Bean pledged he would never again put baseball ahead of his personal life. And when he began a relationship a few months later with Miami Beach restaurateur Efrain Veiga, he quit the game and told his family he was gay.

Another death pushed Bean out of the closet. He had distanced himself from old friends to preserve his secret, and when former college teammate Tim Layana was killed in a car crash in 1997, it was more than a week after the funeral before Bean found out.

“That was the last straw,” he says.

When interviewed a short time later by a newspaper reporter about a restaurant he was opening with Veiga, Bean acknowledged being gay. He recoiled when he saw his admission in print, but the story became national news. There was no turning back.

Brad Ausmus, Bean’s roommate in 1993-95 with the San Diego Padres, says he was shocked to learn his friend was gay.

“At the time I roomed with him, I really had no idea,” Ausmus says. “It probably was in the best interest of his career that he kept quiet. It would have been a strain.”

Bean wishes he could have gotten comfortable with his secret. His premature retirement is his biggest regret.

“That hurts more than anything,” he says. “I walked away four or five years before I could have. I was in great shape. But I didn’t believe I could keep the lies going.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.