Column: How football coach Harry Welch built a Hall of Fame legacy

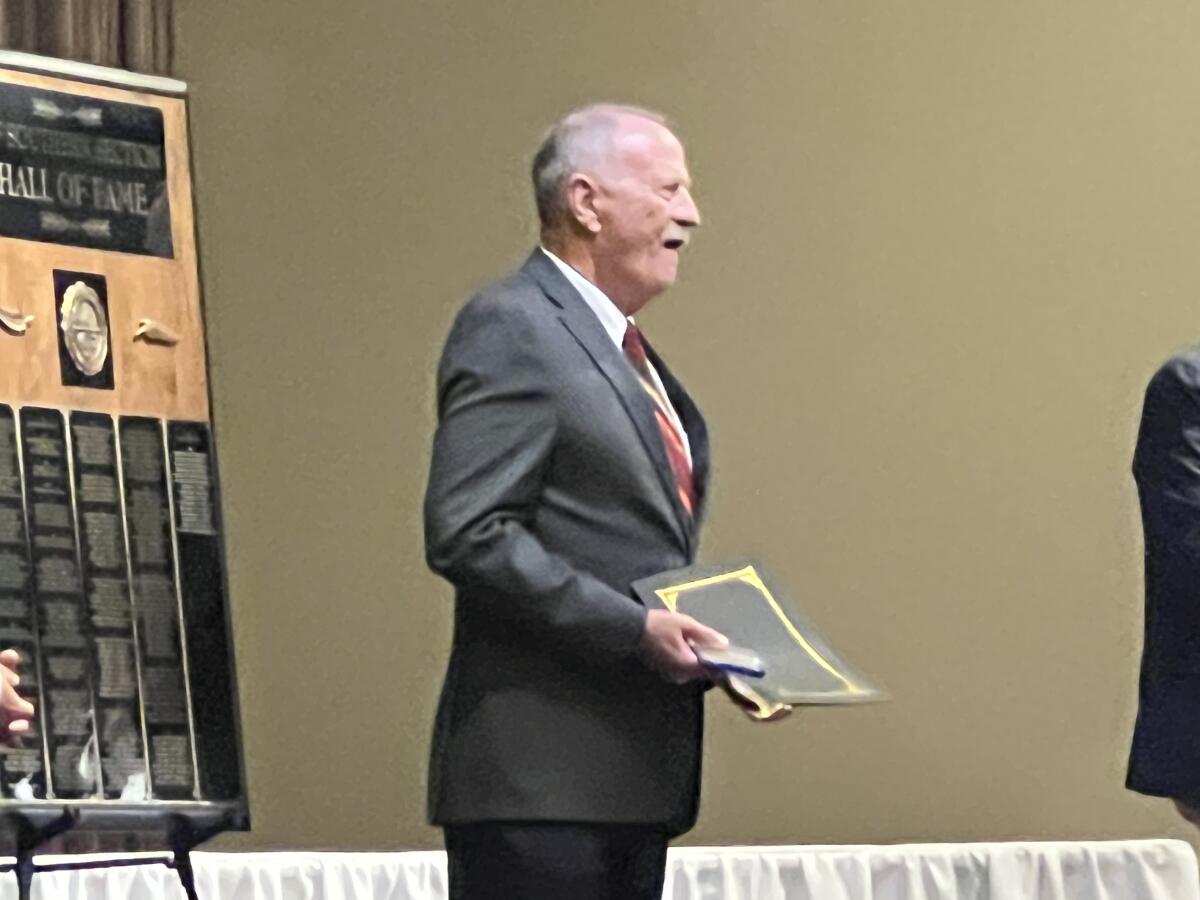

First came the roar, then the applause as more than 70 suddenly rambunctious former players coached by Harry Welch rose from their seats to give him a standing ovation at the Southern Section Hall of Fame induction ceremony in Long Beach.

The only coach to win state championships in football at three high schools — Canyon Country Canyon, San Juan Capistrano St. Margaret’s and Santa Margarita — Welch was a no-brainer Hall of Fame selection. He won nine Southern Section championships and had an .821 winning percentage, second-best all time for coaches with at least 250 victories.

Yet those who have followed his sometimes controversial career since the 1980s through his retirement in 2013 had to chuckle. Welch once sued the Southern Section when it tried to suspend him for one year in 1991 after he conducted an illegal practice. Welch won in court and used the damages to buy a Lexus. So now the same organization that was sued and lost was honoring him.

“He’s earned it,” Southern Section commissioner Rob Wigod said.

There were so many stories being told at the banquet tables of Welch’s influence on players beyond wins and losses that you had to wonder whether to laugh or cry.

“He turns punks into men.”

“He can build you up and tear you down.”

“Every practice was like the Super Bowl.”

Eddie Rodriguez remembers being a 4-foot-11 sophomore at Canyon. One day during practice, he got flattened by a bigger teammate. He immediately got back up.

“Coach is on the other side of the field,” Rodriguez said. “He stops practice. I thought I was going to get yelled at. He said, ‘Eddie, you can play football for me any time.’ ”

Rodriguez would join the Air Force.

The banquet honored 14 men and women during induction into the Hall of Fame, requiring the largest number of banquet tables ever for the event because so many Welch supporters wanted to salute him. Even though many are now in their 50s, they still call him “coach.”

Welch and his wife, Cindee, went from table to table hugging players.

“Coach Welch, if you sit down, the rest will sit down,” said an organizer trying to start the banquet.

John Dahlem, the Southern Section historian who was introducing Welch, joked, “I’m sad to report Harry Welch is here by himself.”

Former Canyon and USC lineman Brent Parkinson surveyed the scene and said, “He’s in his element.”

Welch was a unique coach. First, he was an English teacher who taught Shakespeare and Bible literature. Football players who took his classes thought he was equally tough in the classroom and on the field.

In the 1980s, before it became a trend, he refused to punt on fourth down, even if the ball was on his own 25-yard line. He’d call plays from memory. He didn’t carry a clipboard and didn’t wear headphones. Assistants stayed away from wearing headphones for fear he might blame them if something didn’t work.

He won championships at public schools and private schools. First it was Canyon, where the Cowboys put together a 46-game winning streak and somehow knocked off Concord De La Salle in the 2006 state bowl game, one of the biggest upsets in playoff history. Then he went 42-1 and won another state title at tiny St. Margaret’s.

There were some who gave him little chance of success moving to the tough Trinity League and coaching at Santa Margarita. Another state title came in 2011.

Yes, there were moments that caused some to question his methods. There was the playoff loss to Santa Barbara in 1989 in which he destroyed a trophy case. There was criticism that he yelled too much and practiced too long. There was the time in 2011 when two assistant coaches at Santa Margarita kept coaching despite pleading guilty to marijuana possession charges.

In 2012, for the only time in my writing career, I called for a coach to be removed. It was Welch.

“It hurt me,” he said.

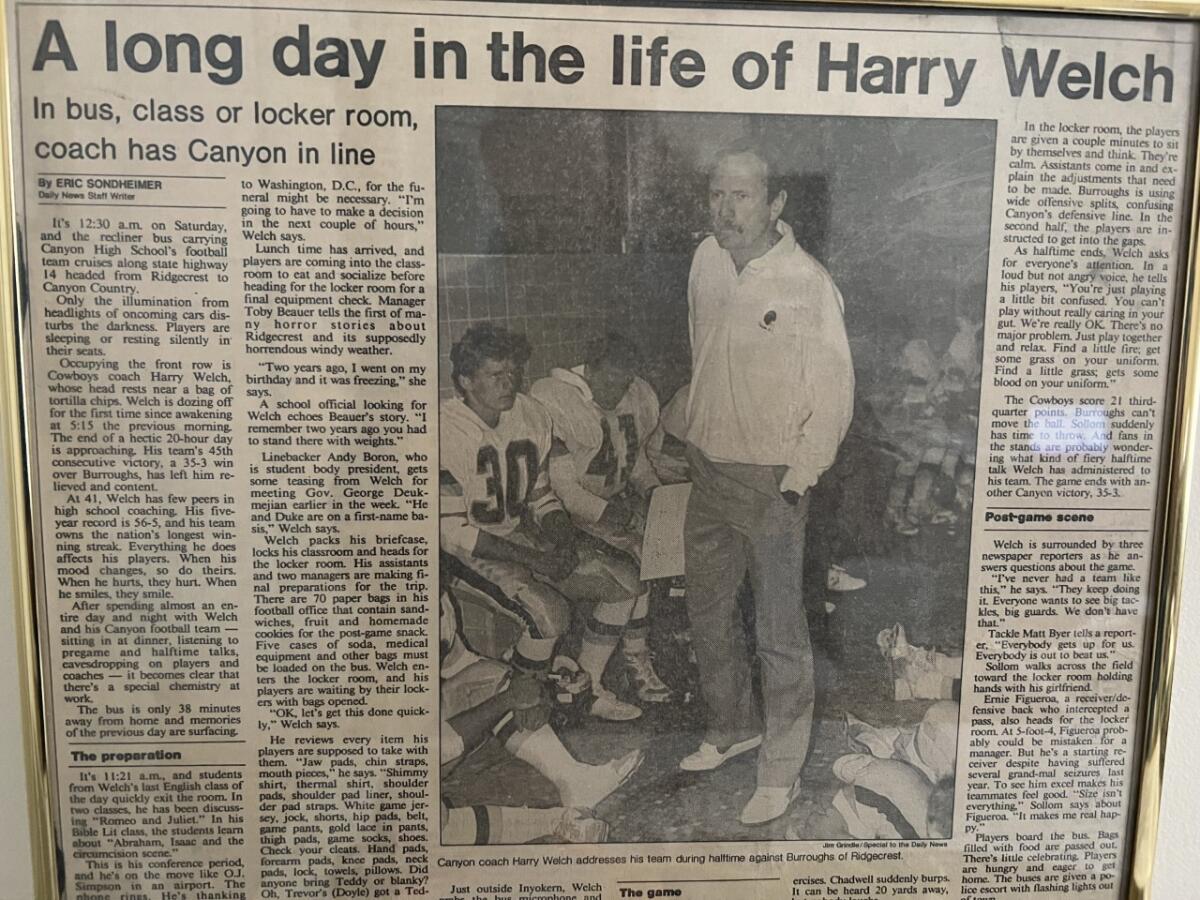

It hurt me, too, because I considered him a good friend and one of the best coaches ever. I still have a framed, cherished story in my house about traveling on the Canyon bus to Ridgecrest Burroughs to offer a day in the life of Welch.

To his credit, Welch didn’t hold a grudge. In the years since, he has been the perfect gentleman, a trusted advisor and even thanked me and sportswriter Steve Fryer in his Hall of Fame video. He has given speeches promoting prostate cancer prevention, warning others to be checked.

Sean Scully, a former Canyon player, put it best regarding how many of his former players feel: “He’s created a legacy of people who love him.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.