Bill Walton once said his dream Final Four field would include five Pac-12 Conference teams. He repeated the motto “Conference of Champions” on basketball broadcasts as if he was being paid by the number of references he could fit into one game.

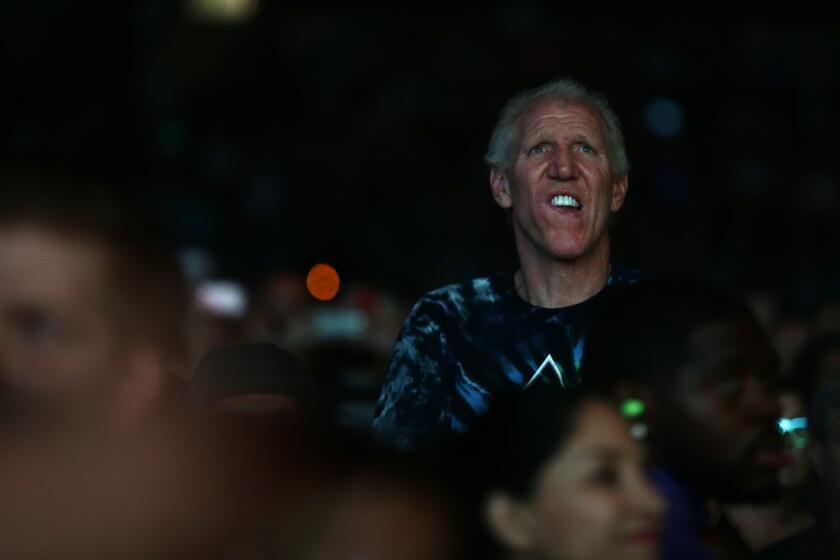

It wasn’t an act — it was Walton being Walton, as colorful as one of the tie-dye shirts the avowed Grateful Dead fan loved to wear.

Walton, the giant redhead whose basketball prowess at UCLA and in the NBA was surpassed only by his zest for life and all its absurdities, died Monday while surrounded by family after a prolonged battle with cancer. He was 71.

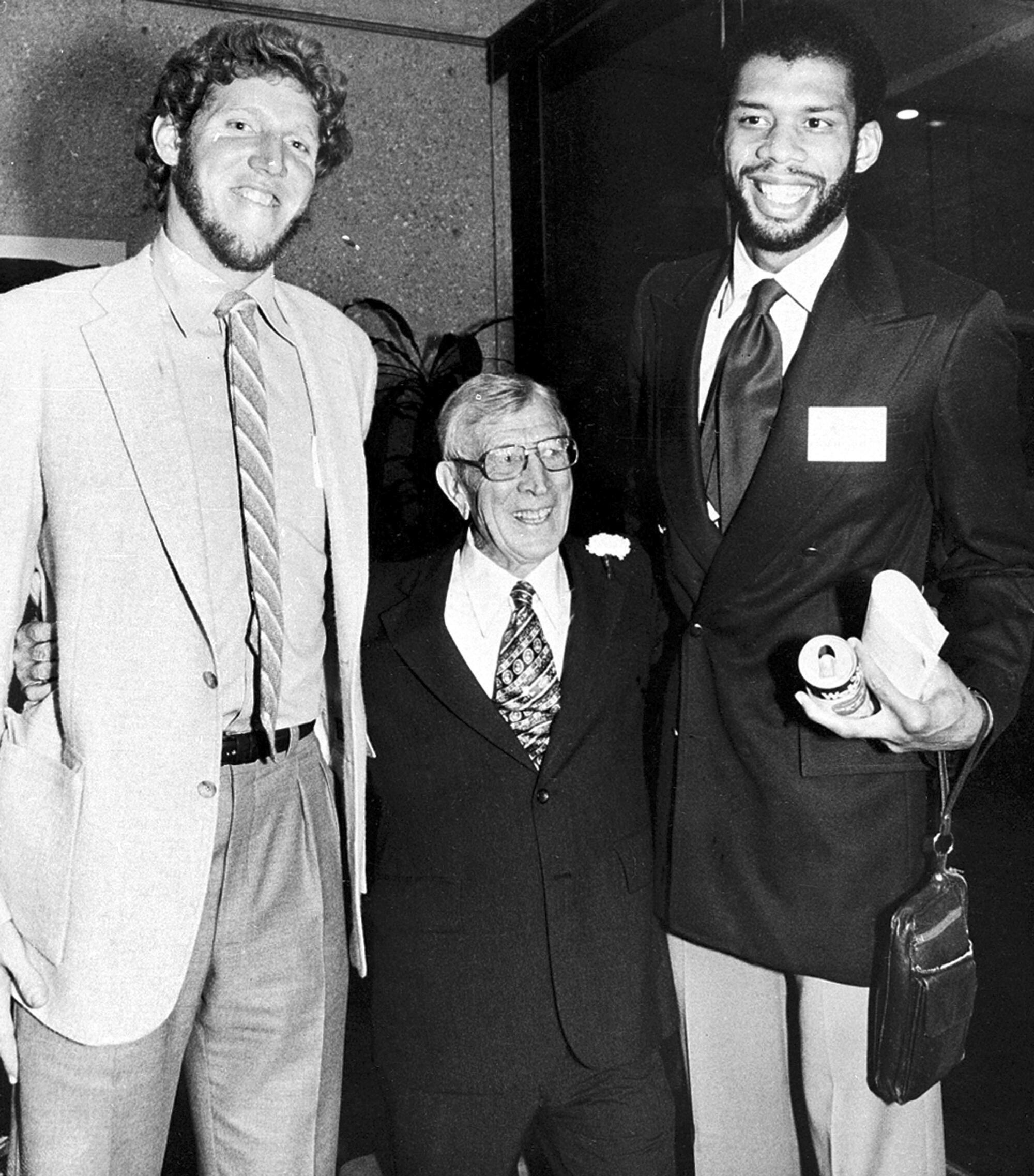

“The world feels so much heavier now,” fellow legendary Bruins big man Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wrote on the social media platform X (formerly Twitter) alongside a picture of the two men smiling with their arms draped across one another. “On the court, Bill was a fierce player, but off the court he wasn’t happy unless he did everything he could to make everyone around him happy. He was the best of us.”

Long after he won two national titles under John Wooden with the Bruins and was selected to the NBA’s 50th and 75th anniversary teams, Walton remained a constant presence in the game he loved as both a broadcaster and de facto ambassador for his alma mater and the Pac-12.

Visible from across any arena, the lumbering big man walked with a hitch in his stride in his later years but always enjoyed dispensing advice to young Bruins players before games and tossing T-shirts to students in the crowd. When fans called out his name inside Pauley Pavilion, Walton would raise both of his giant arms skyward in triumphant acknowledgement.

Known for being gracious with his time, the man who won two NBA titles and was selected to the Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame often made everyone around him feel like the star.

“I never had a better friend, and there are hundreds of others who feel the same way,” longtime Clippers broadcaster Ralph Lawler wrote on X in tribute to the 6-foot-11 center who spent three years with the team when it was based in San Diego before following it up the 5 Freeway for its debut season in Los Angeles in 1984-85. “He leaves a giant hole in our hearts.”

As his illness progressed, Walton’s broadcasting schedule had been noticeably curtailed last season. He also was absent at Pac-12 media day, where he liked to sit quietly in the back of the room and smile while listening to coaches and players talk about their team’s prospects for the season, and the conference tournament five months later.

From calling John Wooden twice a week to pretending to be NBA players on voice messages left for his son, Bill Walton was an eternally kind and quirky soul.

Former UCLA forward Larry Farmer, who went 60-0 in the two seasons he played alongside Walton, said Monday that he last saw his old teammate at a 50-year reunion of the 1973 championship team at Pauley Pavilion.

“We were all in various stages of knee replacements, hips and walking funny while shaking hands,” Farmer said. “It was all something we kind of joked about. I had no idea he was that sick. ... Today, for me, is like having lost a family member. I love him and I’m going to miss him.”

Whenever he called UCLA home games, Walton would stay in the Luskin Center adjacent to Pauley Pavilion and loudly announce his presence, once openly praising the hotel as the greatest in the world as he approached the front desk.

His absurdist streak was constantly on display alongside ESPN broadcaster Dave Pasch, who played the straight man to Walton’s comedian. On occasions when Pasch dared attempt to rein Walton in after one of Walton’s long, rambling soliloquies, Walton would say, “Who are you again?”

Pasch once jokingly challenged Walton to take a bite out of a cupcake with a lit candle atop. After Walton unflinchingly complied, a flabbergasted Pasch said, “Oh, I was kidding!” before breaking into laughter and covering his face with his hand in disbelief.

Walton’s basketball feats left observers equally incredulous. A three-time college basketball player of the year who led UCLA to 73 consecutive wins, he was a central part of the Bruins’ record 88-game winning streak under Wooden.

Known for his relentless shot-blocking, deft offensive touch around the basket and gravity-defying outlet passes, Walton led UCLA to championships in 1972 and 1973, completing Wooden’s record run of seven titles in a row that would later extend to 10 in 12 years.

Walton was unlike anything the college game had seen because he combined a point guard’s savvy and passing skills with the size of a post player.

“Bill was a very intelligent basketball player and he was very fundamentally sound,” Farmer said. “Being 6-11 with that skill set, that’s why you have one of the greatest college players of all time.”

In what was unquestionably his greatest college performance, Walton made 21 of 22 shots — while having four dunks taken off the board because they were not allowed at the time — on the way to scoring 44 points and grabbing 13 rebounds during UCLA’s 87-66 victory over Memphis State in the 1973 NCAA championship game.

In a social media post, Lakers legend Magic Johnson called that feat one of the most dominant NCAA championship performances ever.

“They talk about Jokic being the most skilled center,” Johnson wrote, referring to Denver Nuggets star Nikola Jokic, “but Bill Walton was the first! From shooting jump shots to making incredible passes, he was one of the smartest basketball players to ever live.”

Despite his outsize presence on Wooden’s teams, Walton famously sparred with his coach over issues ranging from Walton’s arrest for lying across Wilshire Boulevard in protest of the Vietnam War to the beard he wore to practice one day.

“Bill, have you forgotten something?” asked Wooden, a stickler for grooming habits, prompting his best player to tell him that he should be able to wear his facial hair however he liked.

“Bill, I have great respect for individuals who stand up for those things in which they believe,” Wooden responded. “And the team is going to miss you.”

Having absorbed the message, Walton sheepishly shaved and returned to practice.

“He raced out of coach Wooden’s office and rode his bike into Westwood and got his hair cut and got shaved,” Farmer said, “and we all chuckled because we knew that was going to happen and no way coach was going to give in.”

During Walton’s final season, the Bruins were upset in a national semifinal during a double-overtime loss to North Carolina State, a blip on the Wooden dynasty that would resume with one final championship in 1975.

The Portland Trail Blazers selected Walton with the first pick of the 1974 draft and he went on to help the franchise win its first and only NBA title in 1977 before being selected the league’s most valuable player in 1978.

But a string of foot injuries sidelined him for three of the next four seasons, and he never recaptured his dominant form. He accepted a reserve role for the Boston Celtics when they won a championship in 1986, capturing the NBA’s sixth man of the year award. The next season would be his last.

“I am sad today hearing that my comrade & one of the sports worlds [sic] most beloved champions & characters has passed,” former Philadelphia 76ers forward Julius Erving wrote on X alongside a picture of himself standing next to Walton in their NBA 75th anniversary blazers. “Bill Walton enjoyed life in every way. To compete against him & to work with him was a blessing in my life.”

Once reticent with the media, Walton became a broadcaster after his playing days ended in an unlikely turn for someone who had struggled with stuttering. Once, when he rose to speak in a UCLA speech class, nothing came out, forcing Walton to return to his seat in shame.

“My classmates just laughed at me, right to my face,” Walton told The Times many years later. “It was the lowest moment of my life.”

With the help of Marty Glickman, a sportscaster based in New York, Walton overcame his stuttering problem at age 28. Glickman told Inside Sports that he advised Walton to say things in order of importance and “keep the rest in his head,” though Walton soon was holding nothing back.

That was apparent when he worked alongside longtime ESPN broadcaster Dick Vitale on several occasions, including LeBron James’ first nationally televised high school game and a Cleveland Cavaliers playoff game involving James.

“On both occasions,” the equally loquacious Vitale told The Times on Monday, “we broke every rule that is taught in broadcasting but had a blast.”

Vitale said he last spoke with Walton about a year ago, when Vitale had called to offer praise about a documentary that detailed the courage Walton had shown in battling his injuries as a player. Returning the favor, Walton offered inspiring words about Vitale’s own battle with vocal cord cancer.

Walton, who was born in the San Diego suburb of La Mesa on Nov. 5, 1952, played both football and basketball as part of an athletic family. His brother Bruce went on to play offensive lineman for UCLA and the Dallas Cowboys in the 1976 Super Bowl, but Bill stuck to basketball after heeding the advice of an eighth-grade coach.

Walton sprouted six inches between his sophomore and junior years at Helix High and stood at 6-10½ as a senior bound for UCLA because of its attractive blend of athletics and academics. He arrived in Westwood in the fall of 1970, when freshmen were not allowed to compete on the varsity team.

He remained close to the program more than half a century later, attending an alumni barbecue at coach Mick Cronin’s house and regularly dispensing nuggets of wisdom to Bruins coaches and players.

Basketball great Bill Walton, who died Monday at age 71, was a noted Deadhead who attended hundreds of Grateful Dead shows and was friends with members of the band.

“It’s very hard to put into words what he has meant to UCLA’s program, as well as his tremendous impact on college basketball,” Cronin said in a statement. “Beyond his remarkable accomplishments as a player, it’s his relentless energy, enthusiasm for the game and unwavering candor that have been the hallmarks of his larger-than-life personality.

“As a passionate UCLA alumnus and broadcaster, he loved being around our players, hearing their stories, and sharing his wisdom and advice. For me as a coach, he was honest, kind, and always had his heart in the right place. I will miss him very much. It’s hard to imagine a season in Pauley Pavilion without him.”

Among the few things Walton disliked were Digger Phelps, the Notre Dame coach whose team edged UCLA by one point in 1974 to snap the Bruins’ 88-game winning streak. Walton went on to needle Phelps over the years, once proudly hoisting a sign reading, “Digger is a wimp” during a UCLA-Notre Dame game that Walton was calling in 2018 at Pauley Pavilion.

When the broadcast team reached Phelps on the phone, Walton eventually asked him, “What are you doing these days? Are you like a vampire that comes out?” After Phelps hung up, Walton said, “Digger is the devil. I thought he was dead.”

The broadcaster also despised the demise of the Pac-12 after UCLA — alongside rival USC — announced its departure for the Big Ten Conference. Walton, who is survived by wife Lori; sons Adam, Nathan, Chris and Luke — the former Lakers player and coach — and three grandchildren, vehemently disagreed with the move as the shattering of more than a century’s worth of history and tradition as part of a soulless money grab.

In a fitting sendoff to both the Pac-12 and his longtime friend, broadcaster Roxy Bernstein quoted Walton at the end of the conference’s final game — Arizona’s 5-4 victory over USC on Saturday in the Pac-12 baseball championship — by saying, “Thank you for my life.”

When a Times reporter passing Walton in the parking lot of the Galen Center after UCLA’s victory over USC in January asked whether he would see the broadcaster in West Lafayette, Ind., as part of the Bruins’ move to the Big Ten next season, Walton turned around, smiled and said it wasn’t up to him.

And then he kept walking and was gone.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.