Does the first team to score 100 points usually win? We checked 27,000 NBA games to find out

Emotions overflow as Clippers announder Ralph Lawler prepares to call his last regular-season game after 40 seasons with the NBA team.

As the game was barreling toward its dramatic conclusion, the Clippers were challenging not only NBA history, but their beloved broadcaster’s famous law.

Ralph Lawler has made the same decree to his audience for more than 40 years: “First to 100 wins. It’s the law.”

On Monday night, “Lawler’s Law” came up with more than three minutes left in the third quarter. The Golden State Warriors led, 100-80, and the Clippers seemed hopelessly behind.

The referees didn’t end the game right there, because Lawler’s Law is plainly not a law. That left an opening for the Clippers, who engineered the largest comeback in the NBA playoff history, rallying from 31 points down.

They won, 135-131, to even their first-round series, an improbable defeat for both the Warriors and Lawler’s Law.

With the 80-year-old Lawler calling the final games of his career, we started wondering: How often does Lawler’s Law still hold true?

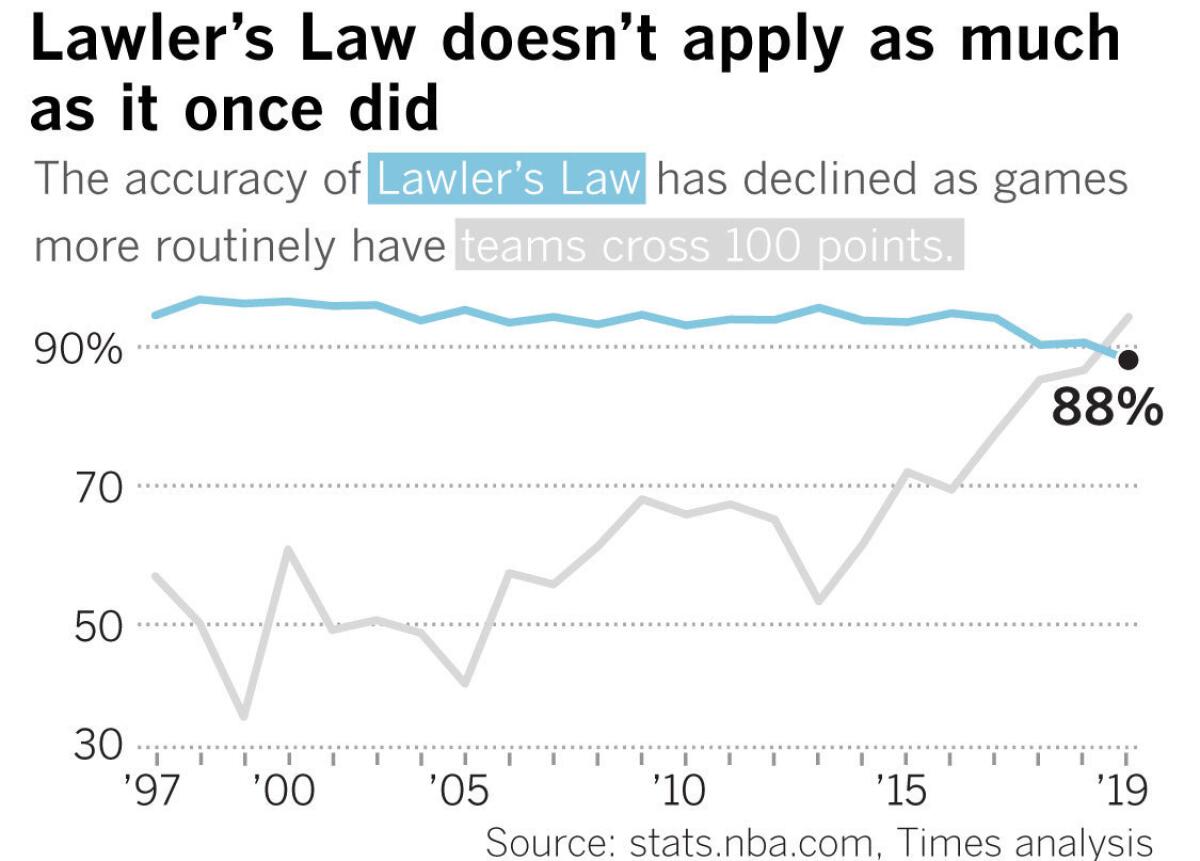

The Times crunched the numbers and found that, aside from being catchy and alliterative, Lawler’s Law turned out to be remarkably accurate. Over the last 23 years, among more than 27,000 NBA games, the first team to reach 100 won 94% of the time.

The reliability of Lawler’s Law appeals even to those devoted to using numbers to find out why teams win.

“When you're doing analytics, you want to be as accurate as you can be but also as simple as you can be,” said Dean Oliver, a statistician who pioneered advanced analysis of basketball data and worked for multiple NBA teams. “You never ignore either one of them. The simplicity of [Lawler’s Law] is what’s good.”

BEHIND THE STORY: How basketball stats bolstered math theory for one number-crunching reporter »

Lawler first made the edict in 1978 as the freshly hired broadcaster for the San Diego Clippers and has used it ever since. It has survived changes in the players, the rules and the way basketball is played.

In recent years, forces have combined to undermine the law, and when the Clippers score 100 first and lose, Lawler hears about it.

“First to 100 wins. It’s the law.”

— Ralph Lawler

“I get angry tweets,” he said. “Like it’s my fault!”

Lawler’s folksy catchphrase is among the many found in local sportscasting. Lakers fans knew a game was over when Chick Hearn said the game was in the refrigerator: “The door’s closed, the lights are out, the eggs are cooling, the butter’s getting hard and the Jell-o’s jiggling.” Jaime Jarrin tells Dodgers fans when a ball clears the fences for a home run, they can “despidala con un beso” or kiss it goodbye.

A vernacular of Lawlerisms formed over four decades of Clippers games, like “Bingo!” to mark a made three-pointer. Or “Fasten your seat belts” when a close game is in its final seconds. And for those moments that generate the most awe: “Oh me, oh my!”

But nothing quite has the ring of Lawler’s Law. He acknowledges the idea was not his alone.

While Lawler was a cub radio broadcaster covering Philadelphia’s sports scene in the 1970s, the NBA faced a challenge from the American Basketball Assn., a renegade collection of teams devoted to an up-tempo, high-scoring brand of basketball. The ABA’s style of play seeped into the NBA and the scoreboard didn’t idle for long.

In the midst of all that scoring, Philadelphia 76ers trainer Al Domenico, a friend of Lawler’s, had a rule of thumb: The team that broke the 100-point barrier first went on to win.

It’s unclear how frequently Domenico was right. Records of the sequence of scoring plays, referred to as the “play-by-play,” were not maintained back then. Still, Domenico’s words stuck with Lawler.

He relocated to San Diego just before the NBA’s Buffalo Braves franchise did the same. On arrival, the team changed its name to the San Diego Clippers and hired Lawler as its commentator. Lawler debuted his law, then heard people shouting it back at him. This was a good sign.

“We didn’t have very many fans in San Diego, believe me,” Lawler said. “So if they heard anything that you said and repeated it to you, you figured that’s pretty good.”

After six seasons in San Diego the team decamped for Los Angeles in 1984. Two trends then started to solidify: the NBA’s scoring began spiraling downward, and so did the Clippers.

Lawler was a steady presence on the airwaves even as his employer became one of the most forlorn teams in professional sports. In their first 33 years in Southern California, the Clippers won more games than they lost just three times.

Lawler always endeavored to have fun despite the losing, figuring that if he remained upbeat the fans would too. Lawler often mixed in heaping doses of self-deprecating humor and jabs at his broadcast partner.

“I don’t think anyone thrives in a game that’s sideways better than Ralph,” said Brian Sieman, the Clippers radio announcer for the last decade and a target of Lawler’s jokes when the two are paired.

Lawler’s homespun style of calling a game was impervious to the changes. In the 1999 season Lawler invoked the law 28 times in Clippers broadcasts. It predicted the winner every time.

But over the last three seasons, something happened to Lawler’s Law. This season, it held true 88% of the time.

What happened? The league rarely stays in stasis. Just as one style of play solidifies, a counter-trend forms and takes over. The law’s fortunes reflect this.

About a decade ago, teams returned to offenses that sprinted toward the basket. The three-point shot, once an ABA gimmick that the NBA adopted in 1979, became a primary mode of scoring.

“Now if you score 100 points, you didn’t score a lot.”

— Danilo Gallinari

This season, the league engineered an even higher-scoring style of play by instructing referees to allow offenses more “freedom of movement.” That gave defenses less leeway to bump, grab or otherwise irritate offensive players without being called for fouls.

Just a few years ago, about one of every two NBA games featured a team reaching 100. This season, Lawler’s Law was invoked in well over 1,100 of the league’s 1,230 regular-season games.

With teams hitting the century mark so frequently, a league-wide fascination with the number 100 has faded.

In the past, fans of the Warriors or Chicago Bulls used to cheer when their teams neared 100 points because the hitting the mark triggered giveaways of coupons for Taco Bell chalupas and McDonald’s Big Macs. Those arenas, among others, now reward fans when the opposing team misses free throws.

“Now if you score 100 points,” Clippers forward Danilo Gallinari said, “you didn’t score a lot.”

Garrett Temple, a newly acquired Clippers guard, remembers playing on a different team that set a goal to keep opponents under 25 points per quarter. If he saw a number under 100 at the end of the night, it was the sign of a good game. That was just three seasons ago.

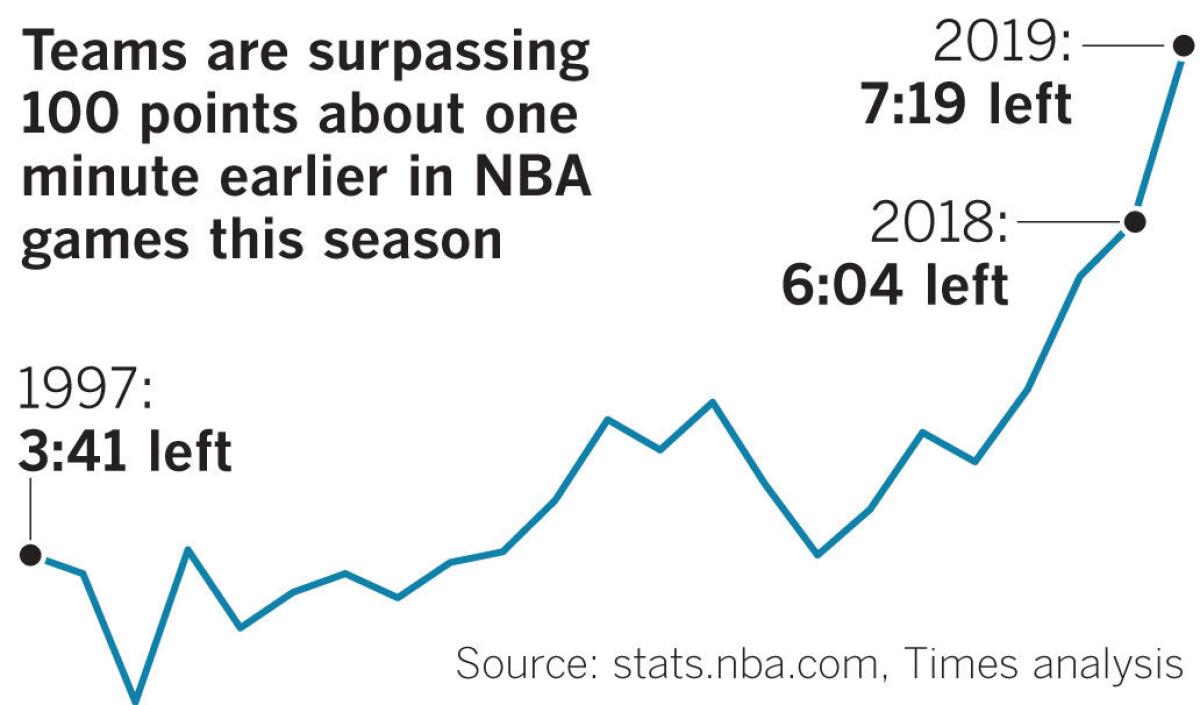

“Nowadays, people might be hitting 100 with nine minutes left in the fourth quarter,” he added. “There’s a lot more game left to play.”

Temple wasn’t too far off. This season, NBA games on average hit 100 with more than seven minutes left in the fourth quarter, according to The Times’ analysis. That’s one whole minute earlier than the season before.

The rate of scoring — teams are averaging 111 points per game — has not been seen in the league since the 1970s, when Lawler was early in his career. He understands why the league has been tinkering with the rules: It gives him a lot more action to describe, which lets fans have more fun while watching.

But if this high-scoring style continues, Lawler’s Law might be in need of an update.

The Times did some more analysis to ask which number might work better in place of 100, and found an answer.

First to 114 wins. It isn’t as poetic, but that’s the law.

Produced by Justin L. Abrotsky.

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.