First in a series exploring the origin stories of three of the Chargers’ top defensive players, each of whom grew up in a small rural town in Florida.

Today, J.C. Jackson, who hasn’t had a football career as much as a football odyssey.

LAKELAND, Fla. — They sold their house, their furniture, Dad’s truck and his motorcycle.

Lisa Dasher and Chris Jackson surrendered their jobs and their friends and trekked 140 miles north, joining Lisa’s oldest daughter in her apartment — her one-and-a-half bedroom apartment.

“We was living in the half,” Lisa recalled, smiling.

Dasher, Jackson and their son, J.C., were three of the seven people wedged into the space, their lives squeezed for the most basic of reasons: They needed money.

Yes, the bills were significant. And so were the circumstances. They had to pay the attorneys trying to keep J.C. out of prison.

“Every success he’s having now is very emotional to me because I know the path,” Lisa said. “I tell people, ‘You don’t understand everything that we had to sacrifice to be here.’ It just wasn’t easy. But I’m glad we made it, man.”

Chargers coach Brandon Staley is a massive tennis fan, and in particular a devout Rafael Nadal fan. He and wife Amy went to Wimbledon for first time.

In March, J.C. Jackson signed with the Chargers, accepting a five-year contract worth up to $82.5 million, $40 million of which is guaranteed.

A team rebuilding its defense added one of the NFL’s top cornerbacks, a tough, resilient, playmaking star coming off his first Pro Bowl appearance and four seasons removed from being a Super Bowl champion.

But the Chargers added more than that because Jackson hardly arrived on his own, his path cluttered by obstacles discouraging to staggering, including a trial that threatened not just his football but also his freedom.

Navigating such a twisting, tortured journey required the strength of more than just one man.

“J.C.,” his dad said, “hasn’t walked alone in his shoes.”

Before he was a Hall of Famer, Edgerrin James was a blocking back, burying opposing tacklers for Chris Jackson during their time together at Immokalee High. James was two grades behind Jackson and, playing in a stacked program, had to wait his turn.

“That’s how it was back in the day,” said John Thomas, a longtime Immokalee coach. “The talent’s usually lined up pretty good around here.”

They called Chris “Action Jackson” because of his athletic prowess. He and his crew labeled themselves “The Raw Dogs” and set out to properly represent their home.

Immokalee is an everyone-knows-everyone town deep in southwest Florida and the heart of industrial agriculture in the United States. They grow an abundance of tomatoes and watermelons down here, a dusty place where there’s genuine value in the dirt.

In the Mikasuki language, Immokalee means “My Home,” and the pride of the people who choose to stay can be as thick as the July humidity.

“If you gonna make it out of Immokalee, you gotta get it from the mud,” said Jackson, 47. “Nothing comes easy in Immokalee. It taught me to grind, to be a strong man.”

Jackson had plans to leave, at least for a while, to pursue a playing opportunity at a small school in Mississippi. Lisa, who was a state-qualifying sprinter at Immokalee, remembers dropping him off at the bus station in Fort Myers and waving goodbye through streaming tears.

But after only a week or so, Jackson was on his way home, where he and Lisa soon enough were welcoming their son.

“I wanted to be in J.C.’s life,” said Jackson, who was raised by his grandparents. “Everything I knew about football, I wanted to put into him.”

They spent hours together in the backyard, Chris firing passes to J.C. and urging him to catch with his fingertips. At age 4, J.C. was spinning around on his father’s command and snagging footballs spiraling toward his face.

Dad was training the boy’s hands, hands that two decades later would carry the reminder of an Immokalee upbringing yet still ignite an NFL career rooted in the ability to catch passes thrown by the opposition.

When he was 5, J.C. scored the first touchdown of his life. It was flag football and he slipped to the outside and sprinted away from everyone. Well, almost everyone.

“I was running right with him down the sidelines, jumping and screaming,” Lisa said. As she did so, she yelled, “He’s gonna play for the Florida Gators! He’s gonna play for the Florida Gators!”

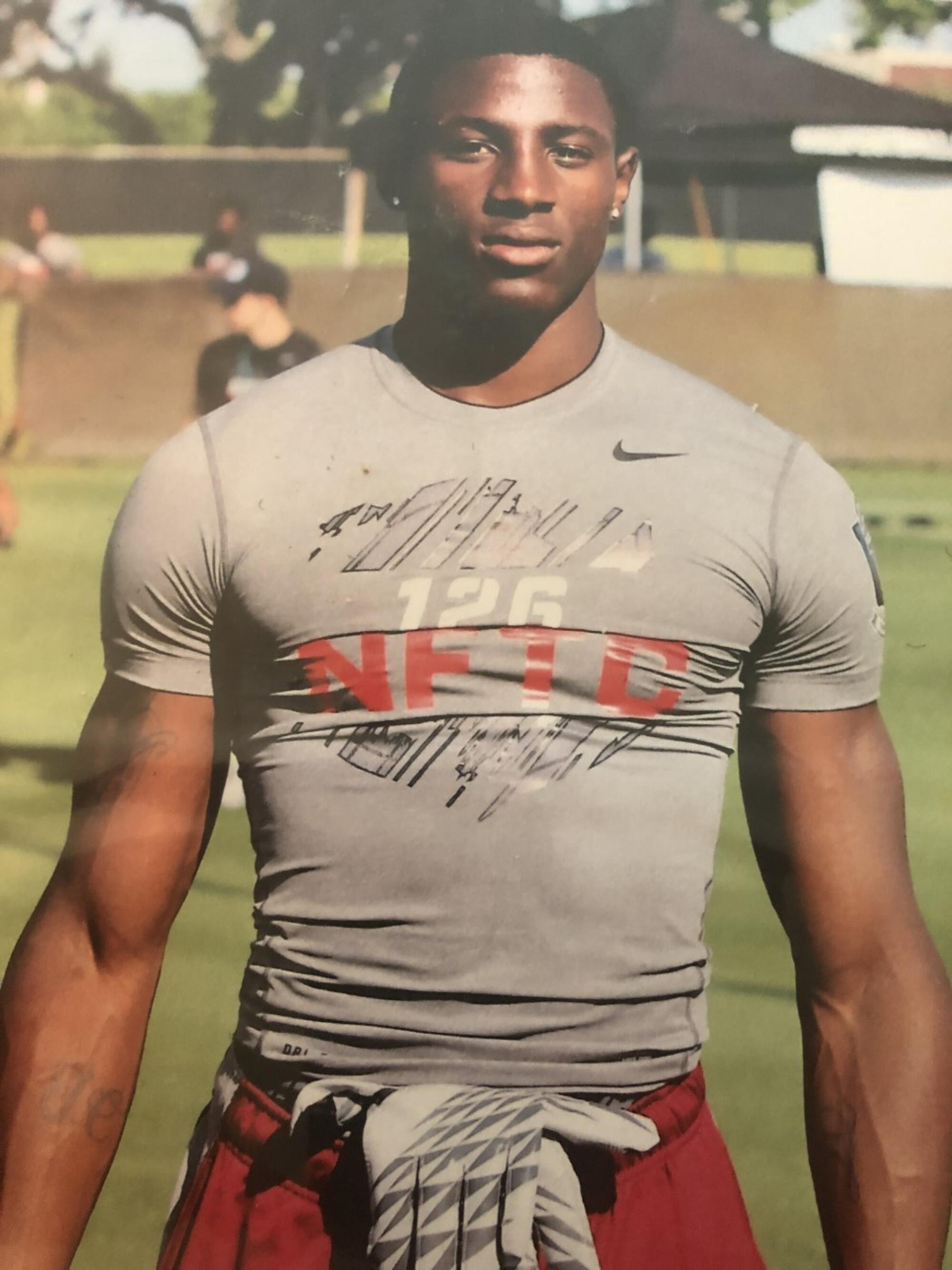

That was the plan too, after J.C. was a four-year varsity starter at Immokalee, his two all-state plaques as a wide receiver now hanging near the school’s main entrance, not far from the plaque commemorating his All-America selection as a defensive back.

“He lit up the stadium right from the start.”

— John Thomas, a longtime Immokalee football coach

Thomas has spent a quarter-century coaching at Immokalee and was in charge of the receivers when he convinced Chris that his son was too talented to play on the freshman team and instead belonged on varsity.

J.C. needed roughly one-half of one game to prove his position coach correct.

“He lit up the stadium right from the start,” said Thomas, who recalls sitting in film sessions on Saturday mornings and wondering what the opposing coaches were thinking trying to cover J.C. one-on-one.

The talent was obvious, and so were the other gifts, most notably the long and athletic body that suggested J.C. could be special, as Chris remembers it, as early as elementary school.

Fort Myers-based trainer LeDondrick Rowe first worked with J.C. during the kid’s sophomore season in high school. All the Immokalee players were lined up in the end zone as Rowe walked along and introduced himself one by one.

“I got to J.C. and asked him what position he played,” Rowe said. “He told me wide receiver. I said, ‘Dude, you’re a defensive back.’ Those were our first words: ‘You look like an NFL defensive back.’ ”

All that work J.C. and his father logged in the backyard — sometimes out there past midnight — was boosted by another level of training, a tough-love regimen Chris employed throughout his son’s development.

Kyle Van Noy, who won two Super Bowls with New England, signed with the Chargers because he is a fan of coach Brandon Staley and sees super potential.

He explained that he “used to cuss J.C. out, just talk harsh to him, ’cause I knew what it takes to make it.” Lisa said she often defended her son as Chris assured her his methods would paid dividends.

During an NFL game two seasons ago, while playing with New England, Jackson was beaten twice by receiver Breshad Perriman for touchdowns — 50 yards in the second quarter and 15 in the third — the latter putting the New York Jets up 27-17.

Following the second score, a television camera caught Jackson slumped on the bench, his head hanging.

“I said, ‘Lisa, I’m in his ear again right now,’ ” Chris said, edging forward in his seat. “J.C. was hearin’ his daddy. I said, ‘Watch, he’s gonna make a play.’ ”

In the final six minutes of the fourth quarter, Jackson picked off Joe Flacco. Four minutes later, New England tied the score en route to a 30-27 victory secured on the game’s last snap.

“All that talking,” Lisa said, “I think that’s what kept J.C. strong through everything.”

During his four years of two-way high school stardom, J.C. emerged as a recruit so sought after that Lisa remembers hiding when someone would show up unannounced and knock on the door.

She also recalled how the Miami coaches arrived one day for dinner in a series of black SUVs with dark-tinted windows. “They rolled up,” Lisa said, “like the President.”

But J.C. chose Florida — fulfilling his mother’s Pop Warner projection — because he was drawn to then-coach Will Muschamp and his defensive coordinator, D.J. Durkin.

It was a shoulder injury that resulted in Jackson redshirting his first season. It was an off-field incident that cost him the rest of his Gators career.

In April 2015, Jackson was arrested and charged with four felonies in connection with an armed robbery in Gainesville. He and two companions were involved, though Jackson no longer was present when the robbery occurred, according to the police report.

Still, he faced those four counts, each carrying a minimum sentence of 10 years and a maximum of life in prison.

“I was scared. Forty years in jail? I might be dead and gone when he gets out.”

— Chris Jackson, on the charges his son faced in connection to a 2015 armed robbery

When officials at Florida informed Jackson he no longer was welcome there, his desire to continue playing led him to Riverside City College, three time zones from Gainesville and an immeasurable distance from SEC country.

That November, Jackson’s lone season at Riverside was interrupted when he had to return to Florida for his trial, which included five days of excruciating uncertainty for parents convinced their son had done nothing wrong but knowing a jury would make the ultimate decision.

Each morning, Chris and J.C. would drive from the cramped apartment in Lakeland to Gainesville, leaving before the sun came up, traveling the 120 miles one way in Chris’ orange Dodge Charger.

Chris said they had to “scrape up gas money” to make it through the week. One of the attorneys the family hired bought J.C. a suit to wear in court.

On those otherwise quiet drives, Chris played what he called “my church music” — “Be Encouraged” by gospel singer William Becton was in heavy rotation.

J.C. would sit back in the passenger seat and, in the darkness, Chris would stroke his son’s head. “Just lovin’ on him,” Chris said.

“I was scared,” the father acknowledged. “Forty years in jail? I might be dead and gone when he gets out.”

On the morning of the final day, Lisa said she wept while wrapping her arms around J.C.

“I hugged him hard ’cause I didn’t know what the verdict was going to be,” she said. “I told him, ‘Remember this: I love you so much.’ He said, ‘Ma, I’ll be back.’ I’m looking at him like, Do you not know what you’re up against?”

Chris said he sat in the back of the courtroom each day with tears in his eyes as he listened to the prosecutor characterize his son as a criminal. At some point during the week, Chris said he stopped eating.

Lisa couldn’t bring herself to attend the proceedings. She remained in Lakeland where she had just started a new job, working in early child care.

She wasn’t allowed to have her cell phone on during business hours, meaning she spent that entire final afternoon unaware of her son’s fate. Asked to explain the experience, Lisa said, “H-e-l-l.”

Up in Gainesville, the jury deliberated for approximately two hours before — in the late morning four days before J.C.’s 20th birthday — acquitting him on all four counts.

At the end of her work day, Lisa retrieved her phone from a desk drawer and turned it on.

“There was so many calls, so many messages,” she said. “ ‘Not guilty! Not guilty! Not guilty!’ All of a sudden, I’m crying and crying and trying to call everybody back at once.”

The jury sided with J.C. after hearing testimony that he arranged the visit in which the robbery occurred but was not otherwise involved. His attorneys argued that the evidence against him was circumstantial.

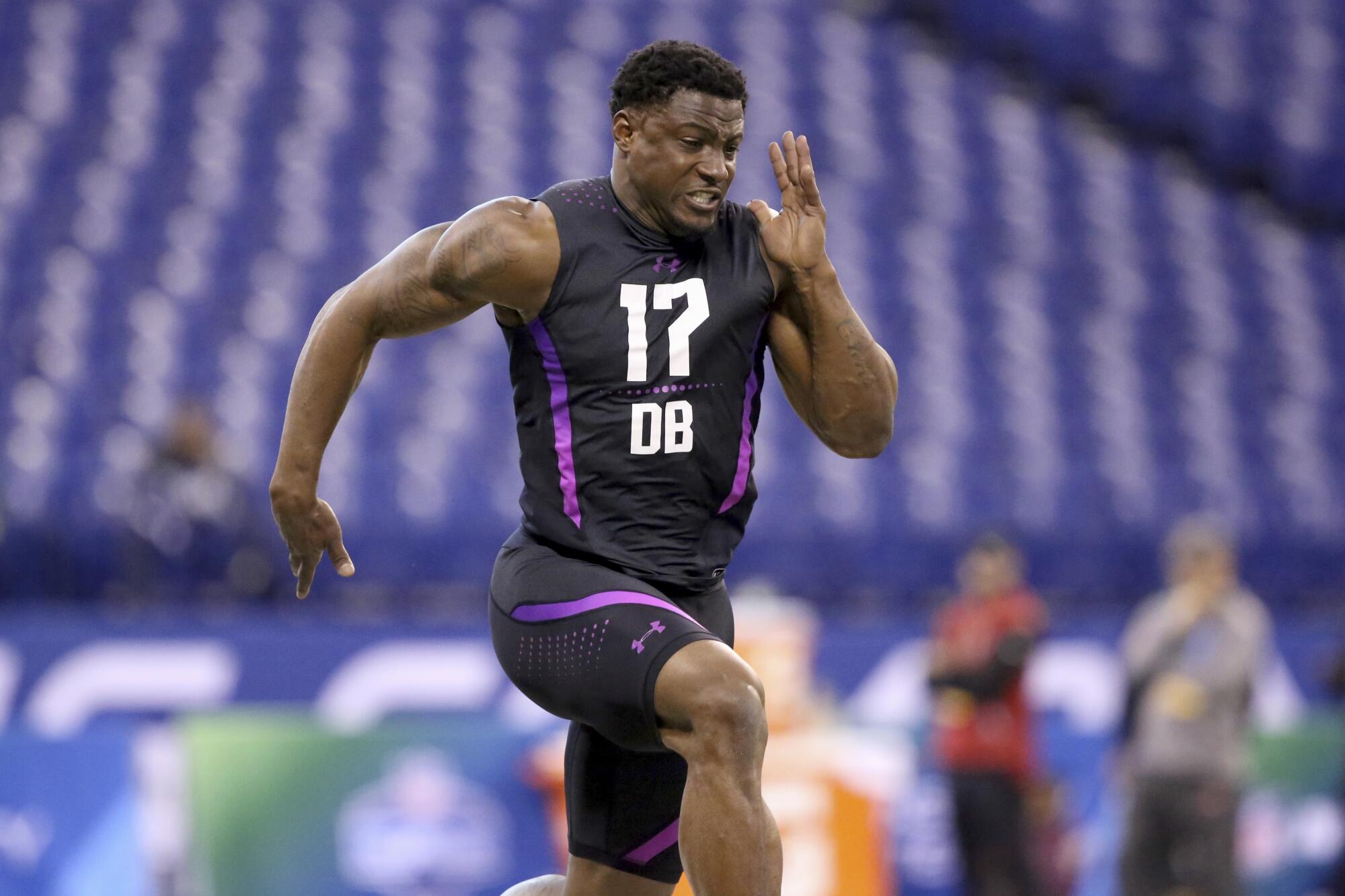

After being cleared, Jackson returned to Riverside, a step that helped put his football career back on track, leading him to Maryland, where he reunited with Durkin, then the Terrapins coach.

In his first Maryland practice, an oft-repeated story goes, Jackson intercepted three passes. He made 23 starts over two seasons and became a draft prospect some observers forecast to go as high as the second round.

“I can’t let it go unknown how much we appreciate what the people at Maryland did for J.C.,” said Lisa, now 48. “We thank them so much.”

“I think J.C. is Immokalee. I saw a kid struggle. I saw a kid grow. I saw a kid overcome. If you’re not tough, Immokalee can overwhelm you.”

— LeDondrick Rowe, trainer who worked extensively with J.C. Jackson

It was after the combine that Jackson — back home and sitting at a Tropical Smoothie Cafe having lunch with his mother — revealed how depressed he was at times in Riverside.

“He just started crying,” Lisa recalled. “I said, ‘J.C., what’s wrong?’ He said, ‘You just don’t know. It was so hard out in California. I was sleeping on floors, not having food. That was the time I wanted to just forget it all.’ It hurt me to my heart hearing that because I had no idea that he was struggling that bad. None of us knew.”

Now, though, all the pain, all the sacrifice would be swept away by the 2018 draft. Having since moved into their own apartment in Lakeland, Chris and Lisa hosted a viewing party.

J.C. was surrounded by the love and support of more than a dozen family members and friends. There was food, including cupcakes made to look like little footballs.

Over three days and 256 selections, the name J.C. Jackson was never announced. Teams took 28 cornerbacks and passed on him every chance they had.

If he was going to make it in the NFL, this cornerback with all the ball skills was going to have to reach out and steal someone else’s roster spot as an undrafted free agent.

And that’s exactly what Jackson did with New England, first starring during scout-team repetitions, flustering at times even all-everything quarterback Tom Brady.

The Chargers have been very cautious with star safety Derwin James, who is recovering from a shoulder injury, but negotiations for a new contract have been deliberate.

As training camp unfolded, Jackson began getting time with the first-stringers. He ended his rookie season appearing in 13 games, with five starts, and launched a four-year stretch in which he intercepted an NFL-best 25 passes.

Those hands, first trained by Dad, soon secured the second-largest signing bonus in Chargers history while offering another example of Jackson’s perseverance.

When his boy was just 7 or 8, Chris got J.C. a job at a watermelon processing plant to expose him to the exact sort of existence he wanted his son to avoid in life.

While he was positioned along a conveyor belt, J.C.’s hand became entangled in the machinery. Seeing blood oozing everywhere, Chris grabbed his son and carried him to a nearby fire station.

The boy spent almost a week in the hospital and required surgery to restore the mangled mess hanging from his arm. In his right hand today, Jackson literally holds the scars of his hometown.

“J.C. is Immokalee,” said Rowe, the Fort Myers-based trainer. “I saw a kid struggle. I saw a kid grow. I saw a kid overcome. If you’re not tough, Immokalee can overwhelm you.”

Over his first three NFL seasons, Jackson played on an entry-level deal before receiving a one-year, $3.4-million contract for 2021.

When he signed with the Chargers, he earned a $25-million bonus on the spot. During the next two seasons, he is guaranteed another $15 million in base salary. The kid from Immokalee had made it, had indeed gotten it from the mud.

His big payday came after Jackson watched his father work in everything from corrections to sanitation — “throwin’ trash,” Chris described it — before becoming a delivery driver.

Lisa has worked extensively with teenage mothers and is employed at Pace Center for Girls.

There are plans for Jackson to buy his parents a new home, something closer to Tampa ... maybe near the water.

In May, he bought each an Audi. Lisa drives hers regularly, while Chris has his in storage. For now, he prefers the 2011 orange Charger, which has eclipsed 200,000 miles.

Chris’ Audi was delivered while he was at work, with no advance warning, a surprise that came with a sticker price of $181,790.

He simply was called outside to the parking lot, where the car was hidden under a cover, with a big red bow on the hood.

There also was a note from J.C., who signed it “#27.”

“Without U,” the note read, “There Is No Me.”

More to Read

About this series

There were stops in Lakeland, Auburndale, Immokalee, Fort Pierce, Vero Beach, Haines City and Davenport.

All in the name of exploring the roots of three of the Chargers’ top defenders — cornerback J.C. Jackson, edge rusher Khalil Mack and safety Derwin James Jr.

Each a small-town legend from a rural Florida outpost before now joining forces some 2,500 miles from home in the intense glare of the NFL.

Along with edge rusher Joey Bosa and cornerback Asante Samuel Jr., both of whom attended St. Thomas Aquinas in Fort Lauderdale, the Chargers’ 2022 defense is, as James smartly noted this spring, “Florida’d out.”

So, presented in three parts over three days, here are the origin stories of Jackson, Mack and James, told largely through the eyes of the parents who raised them.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.