The deeper he wades into the conversation, the deeper Al Michaels is transported back in time, 35 years doing nothing to dull the memory of that warm Sunday afternoon in Anaheim, where the Angels and Boston Red Sox staged one of the most thrilling and head-spinning 75 minutes of October baseball ever.

“To this day, man, I can still feel everything,” Michaels, now 76, said in a recent phone interview. “That freaking game … I mean, the drama from the top of the ninth inning through the bottom of the 11th was just insane.”

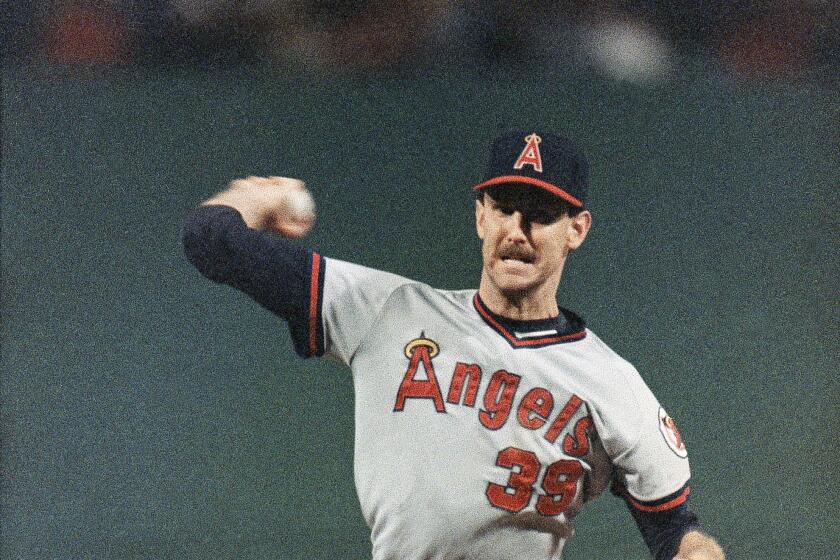

One strike away from delivering the Angels to their first World Series, closer Donnie Moore gave up a crowd-silencing, two-run homer to Dave Henderson in Game 5 of the 1986 American League Championship Series, a dagger that capped a stunning, four-run ninth inning and gave the Red Sox a one-run lead.

The Angels rallied to tie it in the bottom of the ninth and had the bases loaded with one out, needing only a sacrifice fly or well-placed grounder to restore the full-throated roar to an Anaheim Stadium crowd of 64,223. Two of their top hitters, Doug DeCinces and Bobby Grich, failed to bring home the winning run.

Boston left fielder Jim Rice made a game-saving catch of a Gary Pettis drive at the wall to end the 10th inning, and Henderson’s bases-loaded sacrifice fly in the 11th gave the Red Sox a 7-6 comeback victory.

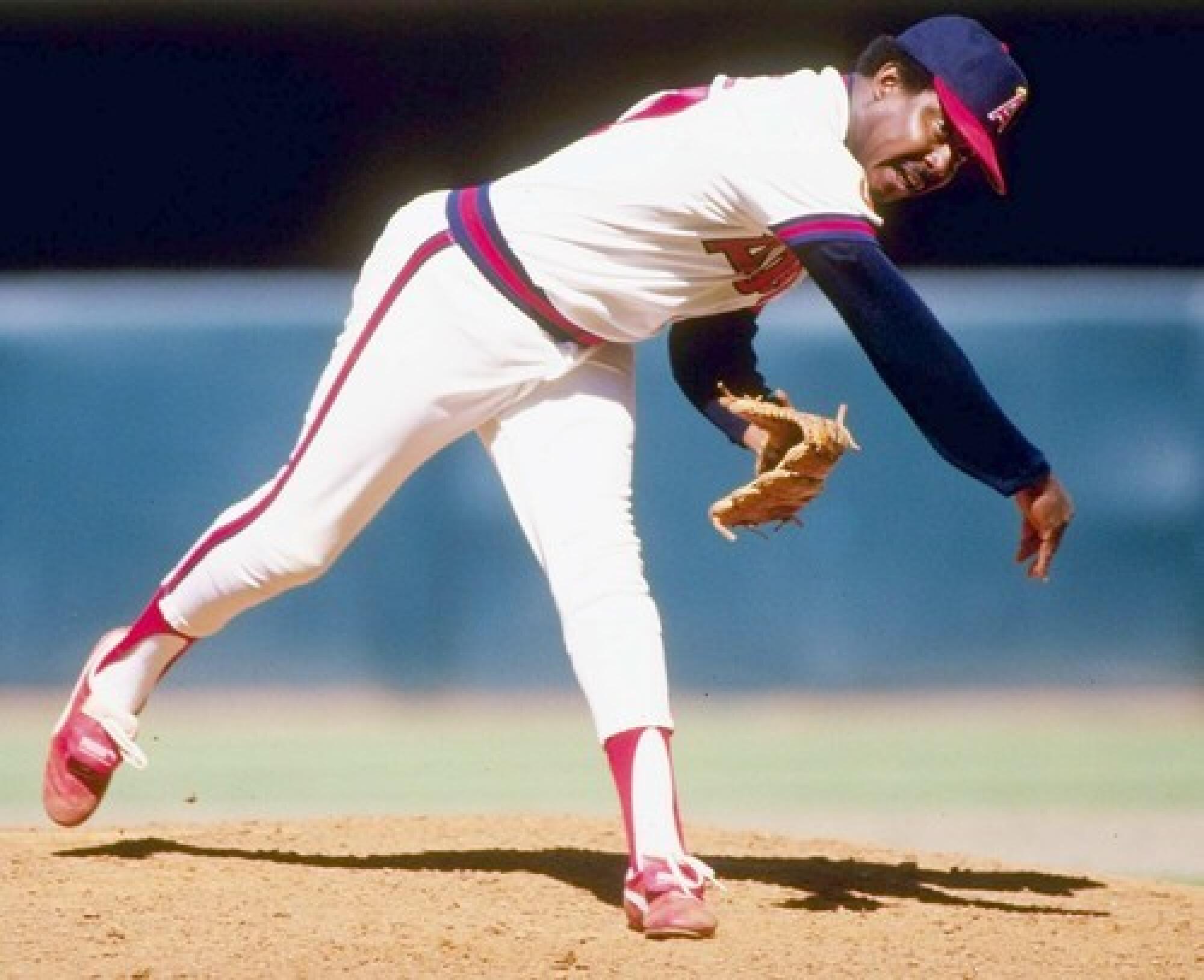

The shellshocked Angels barely put up a fight in Games 6 and 7 losses in Fenway Park. Three-and-a-half decades later, however, it’s Game 5 that still eats at the left-hander who got the final out in the top of the 11th inning but had been bypassed for another southpaw for a key at-bat in the ninth.

The Angels almost wrapped up the 1986 ALCS against the Boston Red Sox until everything changed in the ninth inning of Game 5. Here’s a recap of that series.

“You can’t get any closer,” former Angels pitcher Chuck Finley said. “You almost feel like you can touch it. When you have something in your hands, it’s almost like you were pick-pocketed.”

Tuesday, Oct. 12, marks the 35th anniversary of the most devastating loss in Angels history, 3 hours and 54 minutes of twists and turns that played out like a Shakespearean tragedy.

This is a look back at Game 5 through the eyes of a 23-year-old rookie reliever on that team and a Hall-of-Fame broadcaster who ranks the game just behind the “Miracle on Ice,” the U.S. hockey team’s upset of the Soviet Union in the 1980 Winter Olympics, on his list of greatest sporting events he’s called.

PROLOGUE

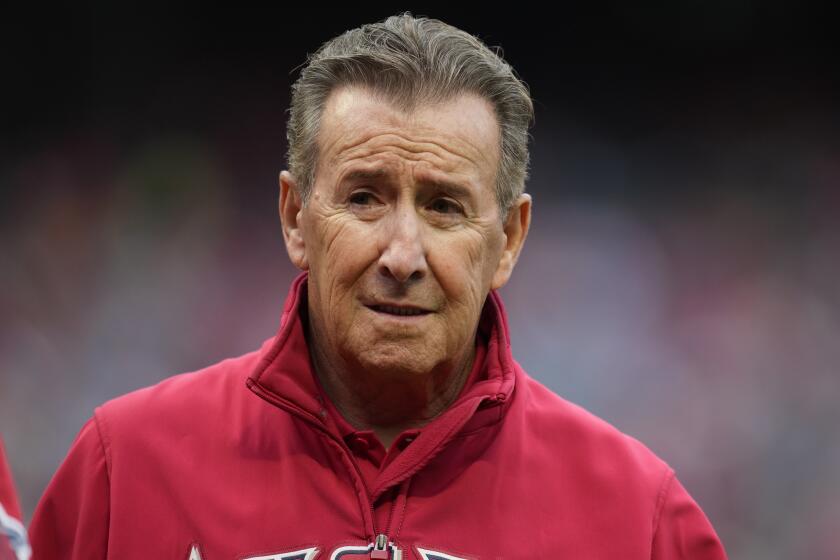

The 1986 Angels, managed by 60-year-old Gene Mauch, were an eclectic mix of crusty veterans, eager youngsters and a sprinkling of players in their prime.

The lineup included designated hitter Reggie Jackson (40), catcher Bob Boone (38), second baseman Grich (37), third baseman DeCinces (35), outfielders George Hendrick (36) and Brian Downing (35) and infielder Rick Burleson (35).

The kids were first baseman Wally Joyner (24) and shortstop Dick Schofield (23).

Don Sutton (41) was the dean of a rotation that included 25-year-old right-handers Mike Witt and Kirk McCaskill. Terry Forster (34) was the elder in the bullpen. Finley was called up from Class-A Quad Cities in late May and saw a blend of personalities and temperaments that was borderline toxic.

“It was almost like a Desperate Housewives for Men the whole year,” said Finley, who lives in Newport Beach and does charity work for the team. “That clubhouse was a mess. Guys were just fighting all the time. There was so much pressure on Gene just to keep that team together.”

Finley recalled the team bus ride in which Moore, angered after being told Mauch had called a workout for an off day, hurled a piece of fruit at the skipper, only to have it splatter on the windshield of the bus. Players could be prickly with the media. And each other.

“It was a mixed bag of nuts,” Finley said. “It was like going to a bar and they give you that bowl. Some are a little sweet, some are a little sour, some are a little salty, but you just keep putting your hands in there and eating it, you know?”

“It was almost like a Desperate Housewives for Men. That clubhouse was a mess.”

— -Chuck Finley

The clubhouse tension, however, did not affect their performance. The Angels went 23-25 in April and May but caught fire in June, going 69-45 over the final four months to finish at 92-70. They sealed the division title with a 21-5 run from Aug. 24 through Sept. 22.

Joyner (.290, 22 homers, 100 RBIs), DeCinces (.256, 26, 96) and Downing (.267, 20, 95) paced the offense. Witt (18-10, 2.84 ERA, 208 strikeouts), McCaskill (17-10, 3.36, 202) and Sutton (15-11, 3.74) led the rotation.

Moore fought through shoulder and rib-cage injuries to go 4-5 with a 2.97 ERA and 21 saves in 49 games, and Doug Corbett (4-2, 3.66 ERA in 46 games), Forster (4-1, 3.15 in 41 games) and left-hander Gary Lucas (4-1, 3.15 in 27 games) were reliable in relief.

“Man, once that national anthem was played, it was just true professionalism,” said Finley, who went 3-1 with a 3.30 ERA in 25 games after his summer call-up. “Those guys knew how to win.”

PENNANT FEVER

The Angels closed the season at Texas and flew to Boston to start the ALCS. Two sloppy, half-well-pitched games yielded two lopsided scores. Witt threw a complete game in an 8-1 Game 1 victory, and Red Sox left-hander Bruce Hurst threw one in Boston’s 9-2 Game 2 win.

The series shifted to Anaheim, where the Angels scored three seventh-inning runs in a 5-3 Game 3 victory and rallied in Game 4 for three ninth-inning runs off Roger Clemens, with DeCinces (homer) and Pettis (RBI double) providing the big blows, in a 4-3, 11-inning win.

The Angels were up 3-1 in the series.

A sense of anticipation filled Anaheim Stadium the next day when the teams met at high noon under sunny, 80-degree skies. The Angels started Witt, their best pitcher. Hurst started for the Red Sox on three days’ rest.

But across the 57 Freeway in a St. Joseph’s Hospital bed sat Joyner, the Angels’ rookie-of-the-year candidate who had a staph infection in his right shin and would watch the game on a 19-inch TV. (That was a fairly big size in those days, kids.)

Grich moved from second base to first, and Burleson started at second. The Red Sox took a 2-0 lead when Rich Gedman, their left-handed-hitting catcher, lined a two-run homer just inside the right-field foul pole in the second inning. Boone’s solo shot to left made it 2-1 in the third.

Grich followed DeCinces’ two-out double in the sixth with a drive to deep center, where Henderson, who had replaced injured starter Tony Armas in the fifth, nearly made a leaping catch on the warning track.

But Henderson’s momentum sent him smashing into the fence, and his left arm hit the top of the wall. The ball squirted out of his glove and over the fence for a two-run homer and a 3-2 Angels lead, which Anaheim increased to 5-2 in the seventh on Rob Wilfong’s pinch-hit RBI double and Downing’s sacrifice fly off reliever Bob Stanley.

Witt, meanwhile, was cruising. He took a six-hitter into the ninth with three of the hits — the second-inning homer, a fifth-inning double and seventh-inning single — coming off the bat of Gedman, who was due up fifth in the inning. With that in mind, Mauch had Lucas warming up alongside Moore as the inning began. Lucas had struck out Gedman twice during the season and again the night before.

An interview platform was constructed in the Angels clubhouse. Clear plastic wrapping was draped over each locker to protect against the anticipated fusillade of champagne. Officers on horseback gathered in the bullpen. California Highway Patrol officers manned the dugouts.

In a 1987 story about the game, former Times staff writer Mike Penner wrote that Jackson walked over to congratulate Mauch, who was on the verge of finally shedding his reputation as the best manager to never win a pennant. But Mauch kept staring ahead from the third-base dugout, watching Witt warm up for the ninth.

“It isn’t over yet,” Mauch said quietly.

“It had merely begun,” Penner wrote.

HEARTBREAK HILL

Bill Buckner opened the ninth with a ground-ball single to center, just beyond the reach of a diving Schofield. Dave Stapleton came on to pinch-run. Rice struck out looking.

Up stepped Don Baylor, the former Angels designated hitter who led the team to its first two playoff appearances in 1979 and 1982. Witt thought he struck out Baylor with a 2-and-2 curve on the inside corner, but umpire Rocky Roe called it a ball.

Witt’s full-count offering was another breaking ball, this one down and away, a pitch Witt later said he “would throw him 100 out of 100 times, and I guarantee you he wouldn’t hit a home run.” Baylor yanked it over the left-field fence for a two-run homer to cut the lead to 5-4.

Dwight Evans popped out to third for the second out. Pitching coach Marcel Lachemann went to the mound and raised his left arm to summon Lucas. The crowd groaned. So did a few Angels players.

“When they took Witt out, it was like, ‘Wow,’ ” Finley said. “He was dominating that game. I know Gedman had decent numbers against him, but I thought Witt was on a roll and he’d figure out a way to get through this.”

Lucas had not hit a batter in four seasons. His first pitch rode up and in and hit Gedman on the right hand.

Out came Lachemann again to summon Moore to face Henderson, who hit .196 with one homer and three RBIs in 36 games for Boston after an August trade from Seattle.

Henderson fouled off a pair of 2-and-2 pitches, a split-fingered pitch and fastball. Moore, whose shoulder was so sore he took a cortisone injection after the game, threw another splitter on the outer half, but this one tumbled instead of breaking sharply toward the dirt.

Henderson reached out and swatted a high fly to left. Four steps out of the box, he leaped high into the air. Finley, from the right-field bullpen, had a perfect view of the ball’s flight. He knew from the sound of the bat, the arc of the ball and the atmospheric conditions, this was not good.

“I watched it come off the bat and went, ‘Oh, sh--,’ because it was a day game and the ball flies,” Finley said. “Then I saw [Henderson] jump and went, ‘Uh-oh.’ We’re one strike away from going to the World Series and boom, that ball goes flying out, and that stadium went silent.”

“To this day, man, I can still feel everything,”

— -Al Michaels

Michaels called Henderson’s homer “unbelievable” and “astonishing” on the broadcast. Henderson floated around the bases and was greeted by jubilant teammates in the dugout.

“Anaheim Stadium was a strike away from turning into Fantasyland,” Michaels said on the air, “and now the Red Sox lead 6-5!”

Moore got Ed Romero to fly to right to end the inning. A stoic Mauch stood in the dugout, arms folded across his chest, a blank look on his face.

“He looked frozen in time,” Michaels said.

PUSH BACK

The Angels clawed back in the bottom of the ninth. Boone singled and was replaced by pinch-runner Ruppert Jones and was bunted to second by Pettis.

Red Sox manager John McNamara summoned left-hander Joe Sambito to face Wilfong, who singled sharply to right. Jones beat a one-hop throw from the strong-armed Evans with a head-first slide to the back of the plate to tie the score 6-6 and re-spark pandemonium in the stadium.

Wilfong should have advanced on the throw home but froze at first. Right-hander Steve Crawford replaced Sambito and gave up a single to right to Schofield, moving Wilfong to third. Had Wilfong taken second on the play at the plate, he likely would have scored on Schofield’s hit.

Downing was intentionally walked to load the bases to set up a force play at home. That brought DeCinces to the plate. Crawford, who was making his first appearance of the series, was so nervous he couldn’t produce any saliva to spit.

“If there was a toilet on the mound,” Crawford said after the game, “I would have used it.”

Instead, the Angels flushed an opportunity down the drain. DeCinces swung at a first-pitch fastball and flied to shallow right, Wilfong holding at third. Grich hit a soft liner that Crawford snagged to end the inning.

“I got no place to sleep tonight,” Mauch quipped after the game. “I bet my house that DeCinces would get that run in from third.”

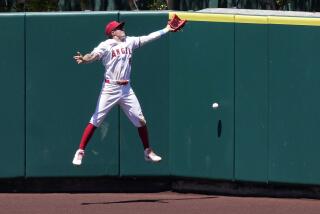

Moore escaped a first-and-third, one-out jam in the 10th by getting Rice to ground into a double play. Crawford walked Jerry Narron with two outs in the bottom of the 10th, and the switch-hitting Pettis, with Narron running on a full-count pitch, drove a pitch to deep left.

Pettis had hit a similar ball over Rice’s head during the big ninth-inning rally the previous night, so Rice took a few steps back for this Pettis at-bat. That allowed him to make a leaping, two-hand catch near the top of the wall to rob Pettis of a game-winning double.

“He had to look in his glove to make sure he caught it,” Michaels said. “Narron was running with the 3-2 pitch, and he scores easily if Rice doesn’t catch it.”

Michaels recalled the stadium becoming “eerily quiet” as the 11th inning started.

“If there was a toilet on the mound, I would have used it.”

— Red Sox reliever Steve Crawford

“I remember saying on the air that the crowd is wrung out,” Michaels said. “They had been screaming for 45 minutes and were just wrung out.”

Moore hit Baylor with a pitch to open the 11th. Evans singled to center. Gedman, the unsung hero of the game, popped up a sacrifice-bunt attempt that fell in front of DeCinces for a single to load the bases with no outs.

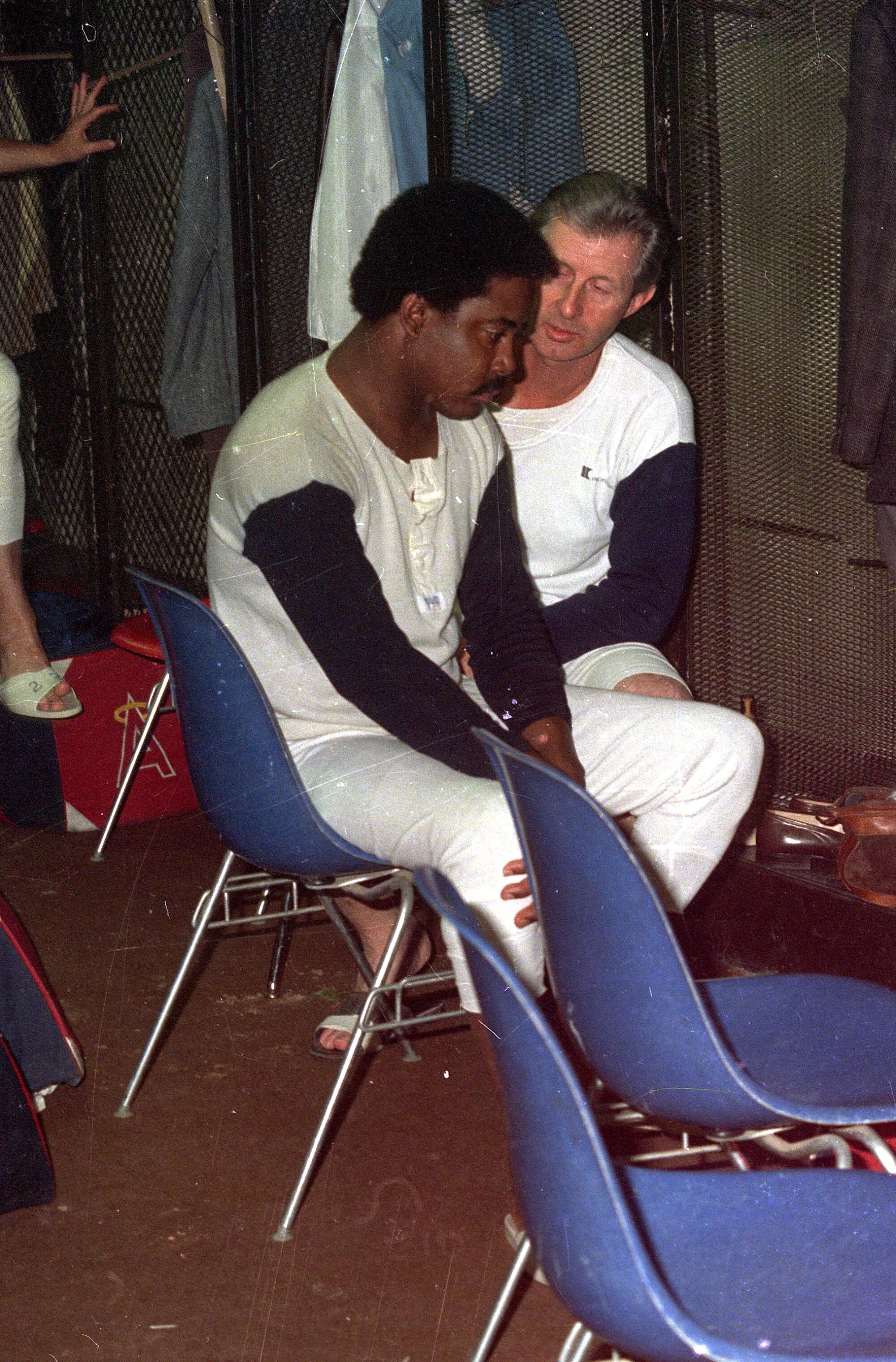

Henderson’s sacrifice fly to center scored Baylor to give Boston a 7-6 lead. Downing made a leaping catch of Romero’s drive before slamming face-first into the wall for the second out, saving a run, maybe two. Finley replaced Moore and got Wade Boggs to ground out to second to end the inning.

Red Sox closer Calvin Schiraldi struck out Wilfong and Schofield to open the bottom of the 11th, and Downing lofted a fly ball into foul territory near first.

“Popped up … here comes Stapleton,” Michaels said on the broadcast. “Next plane to Boston!”

POSTSCRIPT

The Angels’ team flight to Boston was funereal. “It was mute,” Finley said. “Everybody was staring out the windows going, ‘What happened?’ ”

Run-scoring doubles by Jackson and DeCinces in the first inning of Game 6 provided some hope, which was dashed when Boston scored twice in the bottom of the first and five runs in the third in an eventual 10-4 win.

The Red Sox steamrolled the Angels 8-1 in Game 7 to reach the World Series, where they suffered their own one-strike-away collapse against the New York Mets, when Mookie Wilson’s 10th-inning grounder in Game 6 famously rolled through Buckner’s legs to allow the winning run to score. The Mets won Game 7 two nights later.

The career of Moore, who had a history of alcohol abuse and domestic violence, spiraled in the wake of Game 5. He struggled in two more injury-marred seasons with the Angels and was released by the Royals in 1989.

In July 1989, Moore had an argument with his wife, Tonya, and shot her three times with a .45 pistol in their Anaheim Hills home. While the couple’s 17-year-old daughter drove Tonya to the hospital — she survived — Moore, with two younger sons in the house, put the gun to his head and committed suicide. He was 35.

“He was a great guy, he just had some demons he couldn’t tame,” Finley said of Moore. “It’s sad the way it ended up and the way Donnie’s life ended.”

Finley can’t help but wonder if he could have ended Game 5 in the top of the ninth had he been summoned instead of fellow lefty Lucas.

“I think about it all the time,” Finley said. “I don’t know if I would have gotten Gedman out, but I’d like to have had the chance to try. Gary was kind of thumbing it. He was a finesse guy, and I was throwing pretty hard back then. But Gene wanted to go with veterans, so he made what he thought was the book move.”

Finley went on to have a stellar 17-year career, going 200-173 with a 3.85 ERA in 524 games and making five All-Star teams. But he left the Angels to sign with Cleveland in 2000, hoping for a chance to win a championship, two years before the Angels won their only World Series title in 2002.

Finley made seven playoff appearances for the Indians and St. Louis Cardinals in 2001-02 but never reached the World Series.

The closest he would come, it turned out, was with the Angels in 1986.

“I was 23, up from A-ball and one strike away from the World Series — you think it would happen every year,” Finley said. “Then you have a 17-year drought, you’re retired and you don’t have a ring … man, you get that close, it makes you appreciate how hard it is to win one.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.