The Seven Deadly Sins of Angels’ Playoff

BOSTON — Reggie Jackson had taken off his cap and tucked away his glasses in preparation for the inevitable crush of fans on the field.

Champagne bottles in the Angel clubhouse had been opened.

Police were in the Boston dugout and bullpen to make sure the Red Sox were escorted to safety.

The votes had already been tabulated, and Gary Pettis was going to be christened most valuable player of the 1986 American League championship series.

The Angels were going to the World Series.

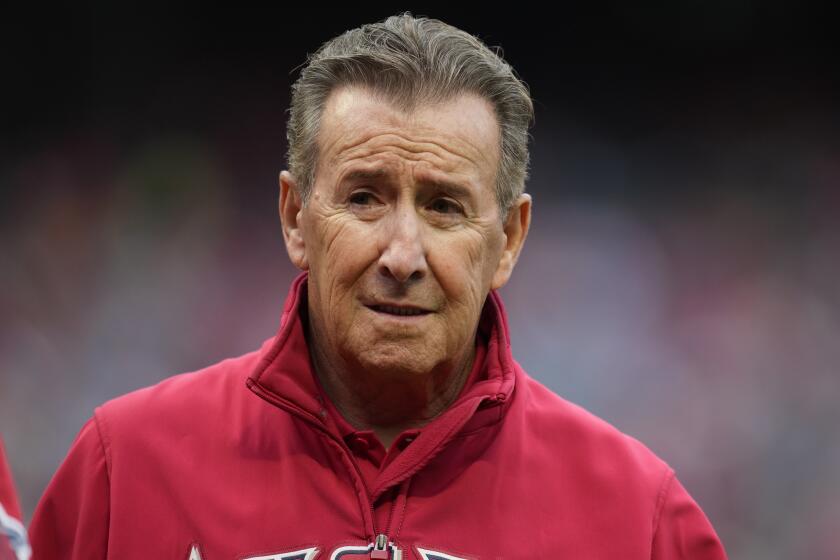

This was going to be the last out of Game 5--and the first hour of Manager Gene Mauch’s deliverance. The count was 2 and 2. Donnie Moore, the Angels’ best relief pitcher, was on the mound. Dave Henderson, a .196-hitting Boston benchwarmer, was at the plate.

Moore pitched. Henderson swung.

Suddenly, for the Angels, everything was blurred.

Henderson’s stunning, crushing two-run homer triggered a chain of events that brought the Angels to where they are today.

Eliminated. Finished for ’86. Also-rans again.

Not even Mauch’s worst nightmare could have equaled the reality of the Angels’ most recent defeat in postseason competition. After 1964 with the fading Phillies, after 1982 with the collapsing Angels, after 25 years of being taunted and haunted by the fates, Mauch had come within one pitch of vindication.

One pitch.

One pitch out of the millions Mauch has watched. One tick of the clock. One note in the sound track of a lifetime.

One pitch.

And now this. The Angel charter has returned to Southern California. The Red Sox, after an 11-year absence, have returned to the World Series. Boston will oppose the New York Mets after obliterating the Angels in Games 6 and 7 at Fenway Park. With the pennant on the line at Boston, the Red Sox outscored the Angels in the final two games, 18-5.

What happened? How, in the span of a mere four days, did the Angels make the plunge from a franchise first to a franchise worst?

After picking through the rubble of this shattered playoff series, a 3-games-to-1 Angel advantage that deteriorated into a 3-4 over-and-out, here are the top seven reasons the Angels bottomed out against Boston:

1. DONNIE MOORE Thirty-five years after the Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff, a baseball playoff delivers another Ralph Branca.

In 1951, Branca of the Brooklyn Dodgers pitches to Bobby Thomson of the New York Giants in a one-game playoff. The Giants win the pennant! In 1986, Donnie Moore pitches to Dave Henderson. The Angels lose the pennant!

In fact, there was more to the Angels’ demise than Moore’s fateful 2-and-2 pitch in the ninth inning of Game 5. The Angels tied the score in the bottom of the ninth--and lost in the 11th--and traveled back to Boston, where they had two opportunities to right this wrong.

But it could be argued that the Angels were finished as soon as Henderson’s two-run homer off Moore cleared the fence. The blow ravaged the spirits of the Angels and resuscitated the Red Sox.

“I’ll shoulder the blame,” Moore said in the aftermath of Game 7. “Somebody’s got to take the blame, so I’ll take it. We were one pitch away from going to the World Series . . . and I threw that pitch. I lost that game.”

In fairness to Moore, he was playing with pain. Immediately after Game 5, he received not one, but two cortisone injections--in his right shoulder and in his right rib cage. Moore should have been handled with extraordinary care in this series.

Which brings us to . . .

2. MOVES BY MAUCH The ninth inning of Game 5 will be inspected and dissected by baseball historians for years.

Should Mauch have stayed with starting pitcher Mike Witt, who had thrown just 121 pitches and was one out from his 16th complete game of 1986?

Should Mauch have brought in Moore, who was obviously off form? Moore had saved Game 3 but looked awful in doing it--yielding three hits, a walk and two runs in the eighth inning. In Game 4, during which the Angels used four relief pitchers, Moore was so sore he didn’t even warm up.

By Game 5, Moore declared his arm to be “85-90% sound”--which may have been an optimistic appraisal.

Witt’s arm was 100% sound. He had given up a two-run homer in the ninth to Don Baylor, making the score 5-4, but had just retired Dwight Evans on a pop-up for the second out.

“Mike gave up the home run to Don Baylor, but against Evans, he looked like typical Mike Witt,” said Doug DeCinces, who caught Evans’ popup. “I thought Mike was going to do it.”

But Witt didn’t get the chance. Mauch relieved him, first with Gary Lucas and then with Moore--and the Red Sox got back off the floor.

“I’ve never had much success relieving Mike Witt,” Mauch admitted. “The other team is always so glad to see him go.”

The Red Sox certainly were. Said Evans, summing up Boston’s mood when Mauch made the move: “Thank you.”

Games 6 and 7 were blowouts, but Mauch might have kept things closer by moving sooner. Instead, he let Kirk McCaskill pitch until he was down, 7-2, and John Candelaria pitch until he was down, 7-0.

Yet in Game 5, Mauch pulled Witt, 18-game winner and Cy Young Award contender with a 5-4 lead.

3. DOUG DeCINCES, GAME 5 Sure, DeCinces had two doubles in his first four at-bats Sunday, scoring on Bobby Grich’s sixth-inning homer that traveled into and out of Henderson’s glove. But in the bottom of the ninth, with the score tied and the bases loaded with one out, DeCinces swung at the first pitch and lofted it to shallow right field--far too short for a sacrifice fly.

DeCinces was facing a young pitcher, Steve Crawford, who was making his first postseason appearance and who hadn’t retired a batter, having given up a single and an intentional walk. Crawford might have exposed some nerves had DeCinces waited him out.

In this case, a walk or a wild pitch is as good as a hit.

Instead, DeCinces went for broke right away. And he hit a ball to the only part of the outfield--Dwight Evans’ territory--where that ball could not have scored Rob Wilfong from third base.

Even Mauch admitted surprise.

“I got no place to sleep tonight because I bet my house DeCinces would get that run in from third,” he said.

4. WALLY JOYNER’S SHIN It’s an easy excuse, but it’s a legitimate one. Without Wally Joyner, the Angels are a different team.

With Joyner, the Angels had a 2-1 edge over the Red Sox. Joyner doubled twice in an 8-1 victory over Roger Clemens in Game 1. In Game 2, he became the first American League rookie to hit a home run in the playoffs. In Game 3, he singled and scored a run, raising his playoff batting average to .455.

The Angels were on their way to the World Series, and Joyner was on his way to MVP.

Then came the infection in Joyner’s right shin that kept the first baseman out of his club’s last four games. The Angels lost three of them--and had to go 11 innings to win one.

Without Joyner, the Angels came up lacking both offensively and defensively. His replacements at first base, Grich and George Hendrick, batted .208 and .083, respectively. Grich made a crucial error at first base in Game 6, and Hendrick, basically, is a sieve.

With Joyner hospitalized, the Angels were left with just two dangerous bats in their batting order. The Red Sox strategy was reduced to pitching around DeCinces and Brian Downing--a strategy that proved a major success.

5. KIRK McCASKILL Not much needs to be said about Kirk McCaskill’s performance in this playoff series. A look at the pitching lines in both of his starts will suffice.

Game 2: 7 innings, 6 runs, 10 hits, 3 walks, 9-2 Angel defeat.

Game 6: 2 innings, 7 runs, 6 hits, 2 walks, 10-4 Angel defeat.

Playoff record: 0-2, 7.71 earned-run average.

At 25, McCaskill won 17 games. But against Boston, those 25 years were more evident than the ability that enabled him to win those 17 games. In two of their four victories, the Red Sox shook young McCaskill, rattled him and rolled over him.

6. DEFENSE “This team doesn’t beat itself,” Mauch said before Game 1. The 1986 Angels had the best fielding percentage in the franchise’s history, said the record book.

So what happened when the Angels needed their defense the most?

It rested.

In a farcical Game 2, the Angels tied a playoff record by committing three errors in one inning. And that wasn’t including the pop fly that Grich couldn’t track down or the ground ball that McCaskill claimed he lost in the sun.

In Game 6, Grich threw a ball into the photo area behind first base during a five-run third inning for the Red Sox.

In Game 7, the team’s two most respected glove men, Pettis and Dick Schofield, both made errors, opening the gates for seven unearned runs.

The Angels ended up tying another record--most errors in a series, 8.

7. MR. OCTOBER It’s time to scrap that nickname once and for all. Reggie Jackson had undeniably great World Series in 1977 and ’78 and has been living off them ever since.

This is how Mr. October has fared in the postseason this decade:

1980: No home runs, no RBIs, a .273 average against Kansas City in the playoffs. Kansas City wins.

1981: A .333 average but only one home run and one RBI against the Dodgers in the World Series. Jackson also drops a ball in right field that leads to a Dodger victory. Dodgers win.

1982: One home run, two RBIs, a .111 average against Milwaukee in the playoffs. Milwaukee wins.

1986: No home runs, two RBIs, a .192 average against Boston in the playoffs. Boston wins.

In what may be his last playoff appearance, Jackson struck out seven times in 26 at-bats and left a total of 13 runners stranded--including a ground-out with the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth in Game 4.

Mr. October? For Jackson and the Angels, who have now collapsed twice in the playoffs in the last five years, a more accurate tag would be Missed in October.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.