Dolores Canales fights for an end to solitary confinement

Dolores Canales remembers the cold cement floor, indifferent brick walls and the thick metal door that separated her from the rest of the world.

Like many in solitary confinement, she craved a shred of human contact.

“You could yell out the door to people … so we would do that sometimes as a form of communication,” Canales said. “But at the end of the day, you still know you are in isolation.

“You still have those brick walls to stare at. You still have the anxiety that comes at night. It just feels like you are being buried alive.”

Years later, Canales — decades removed from her drug-related struggle with the criminal justice system — advocated for her son, John Martinez, as he took part in hunger strikes at Pelican Bay State Prison to demand an end to indeterminate solitary confinement. The hunger strike was the largest prison protest in the state’s history.

Canales and several families started the group California Families Against Solitary Confinement in 2011 to support and advocate for their incarcerated family members involved in the highly publicized hunger strike in the state’s highest-security prison.

The strike and a related lawsuit resulted in the end of indeterminate solitary confinement in California.

“Why did a thousand people even have to go without eating for a few days to get these things resolved?” Canales said. “It’s the only way to get people to listen.”

Today, Canales, 60, of Fullerton, helps lead the group as they attend hearings, speak with legislators, hold rallies and advocate for an end to solitary confinement.

Canales has brought her advocacy to Orange County, where she’s partnered with several groups to work towards ending solitary confinement.

“She is the perfect example of why this work and movement should be led by impacted people,” said Daisy Ramirez, Orange County jails conditions and policy coordinator at the ACLU. “She knows firsthand what it’s like to be confined in a cage for years on end. She knows what the treatment is like behind bars. She knows what families go through when they have families that are incarcerated.”

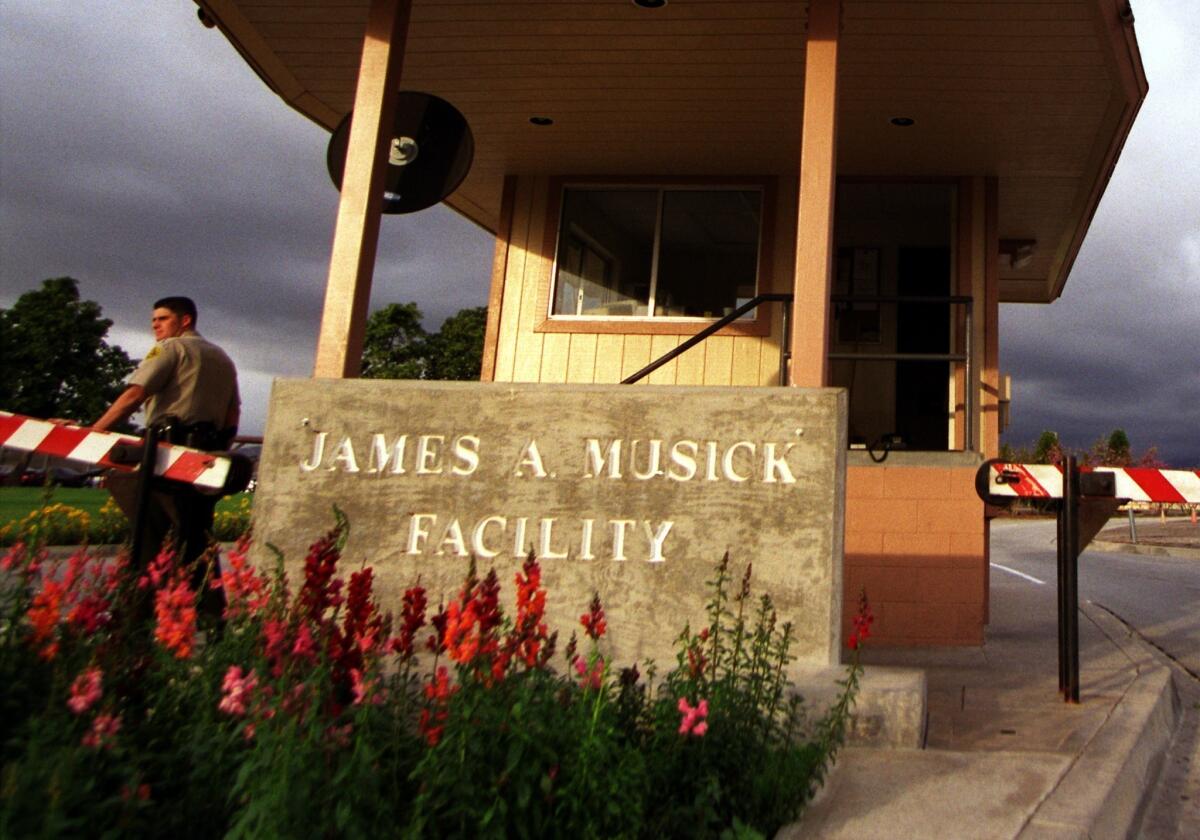

Ramirez and Canales have been working together since 2018, when Orange County inmates organized a seven-day hunger strike to protest jailhouse conditions. Canales said Martinez committed second-degree murder as a young adult and is now incarcerated in the Theo Lacy facility in Orange. He took part in that hunger strike.

The ACLU has set its sights on solitary confinement for years.

“Long-term isolation costs too much, does nothing to rehabilitate prisoners, and exacerbates mental illness — or even causes it in prisoners who were healthy when they entered solitary,” the ACLU‘s website says.

Ramirez said Orange County jails use solitary confinement but call it “disciplinary housing.”

“Disciplinary housing is short-term temporary housing used for inmates who violate rules designed to keep themselves, other inmates and staff safe,” Orange County Sheriff’s Department spokeswoman Carrie Braun said in an email. “We utilize a progressive discipline model for inmates who violate jail rules, and disciplinary housing is a last resort. The Orange County Sheriff’s Department is committed to providing a safe environment for the inmates entrusted to our care.”

Ramirez said inmates are confined for 23 hours a day with limited access. She said they hear from inmates who are placed in disciplinary housing for “arbitrary reasons.”

According to the Sheriff’s Department custody operations manual, Orange County jail inmates cannot be placed into disciplinary housing for more than 30 days without three “relief” days.

An inmate in disciplinary housing loses privileges for television, outdoor recreation, public visits, personal phone calls, access to newspapers and other publications, cards or games and “unnecessary inmate movement” outside of the cell.

Orange County jail inmates may be placed into disciplinary housing for not obeying directives from staff, not showing respect to staff or causing a disturbance in the jail, according to the manual.

Rules for respecting staff include not making “false statements” to jail staff and referring to them by their title — “Deputy,” “Sir” and “Nurse” are the examples given by the manual. Inmates cannot call staff by their first name.

Medical and mental health staff is supposed to clear inmates prior to being placed in disciplinary housing.

However, Ramirez is concerned that inmates with mental health issues are wrongfully subjected to disciplinary housing, which further exacerbates their psychological issues.

“Someone in a full mental health crisis may be experiencing some level of paranoia and doesn’t really comprehend what is being asked of them — those folks are often written up for failing to obey a directive from jail staff,” Ramirez said.

“People with mental health needs are essentially being punished for being in a mental health crisis and because the department has no idea how to deal with the situation, those people get written up and thrown in the hole, which we know will only exacerbate the trauma they are experiencing.”

Canales and Ramirez said the Orange County jails have been using disciplinary housing as a means to social distance during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Braun denied that the department is doing this. However, the custody operations manual states that disciplinary housing may be used for “medical quarantine.”

More recently, Canales helped advocate for Orange County inmates during a hunger strike at Theo Lacy jail in early July. Inmates demanded a return to hot meals and family visitations, which had been discontinued due to the virus. Martinez took part in that strike as well.

Canales said she has been working to get the Sheriff’s Department to allow those in disciplinary housing to be able to purchase food from the commissary to supplement the minimal food they are getting during the pandemic.

The Sheriff’s Department manual states that inmates in confinement are suspended from using the commissary.

Canales said she doesn’t trust Orange County law enforcement due to a track record of misleading the public, pointing to the evidence mishandling and illegal jailhouse informant scandals. The Orange County jails were also caught recording thousands of calls between inmates and their attorneys over several years.

“There is zero accountability for misconduct in Orange County,” Canales said.

The ACLU has been working to get better conditions in Orange County jails and two Orange County Grand Jury reports over the last few years found deficiencies with jail conditions.

Canales said she will continue to advocate for an end to solitary confinement in Orange County and at the state level, drawing on her experiences and those of her son.

“There is no one better equipped to lead this fight,” Ramirez said.

All the latest on Orange County from Orange County.

Get our free TimesOC newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Daily Pilot.