An O.C. deputy filed evidence late in a majority of his cases. Then he got promoted

An Orange County sheriff’s deputy accused of mishandling evidence was promoted to sergeant less than a year after the Sheriff’s Department referred his case for possible criminal prosecution, a public defender alleged recently in court filings.

The sergeant, Philip Avalos, failed or was late to book weapons, drugs and other property in 51 cases, according to internal Sheriff’s Department documents filed by Assistant Public Defender Scott Sanders in court March 2. The documents, detailing cases from 2016 to 2018, were submitted as part of Sanders’ discovery motion in a drug case.

The revelation marks the latest development in a growing scandal involving improper booking practices by more than a dozen deputies. The department’s policy requires evidence to be booked by the end of each shift, but an internal audit in 2018 found that deputies routinely booked evidence late or failed to book evidence completely.

Avalos, in one instance, took nine months to book a machete he seized from a suspected gang member during a 2017 traffic stop in Anaheim, according to Sheriff’s Department investigation.

“This casts a tremendous shadow of doubt on the department’s willingness to stop this kind of conduct if he’s put in a leadership role over other deputies,” Sanders said in an interview last week. “At its core, the willingness to promote someone like him says this kind of conduct is absolutely acceptable in this department.”

Sheriff’s officials declined to comment on Avalos’ case.

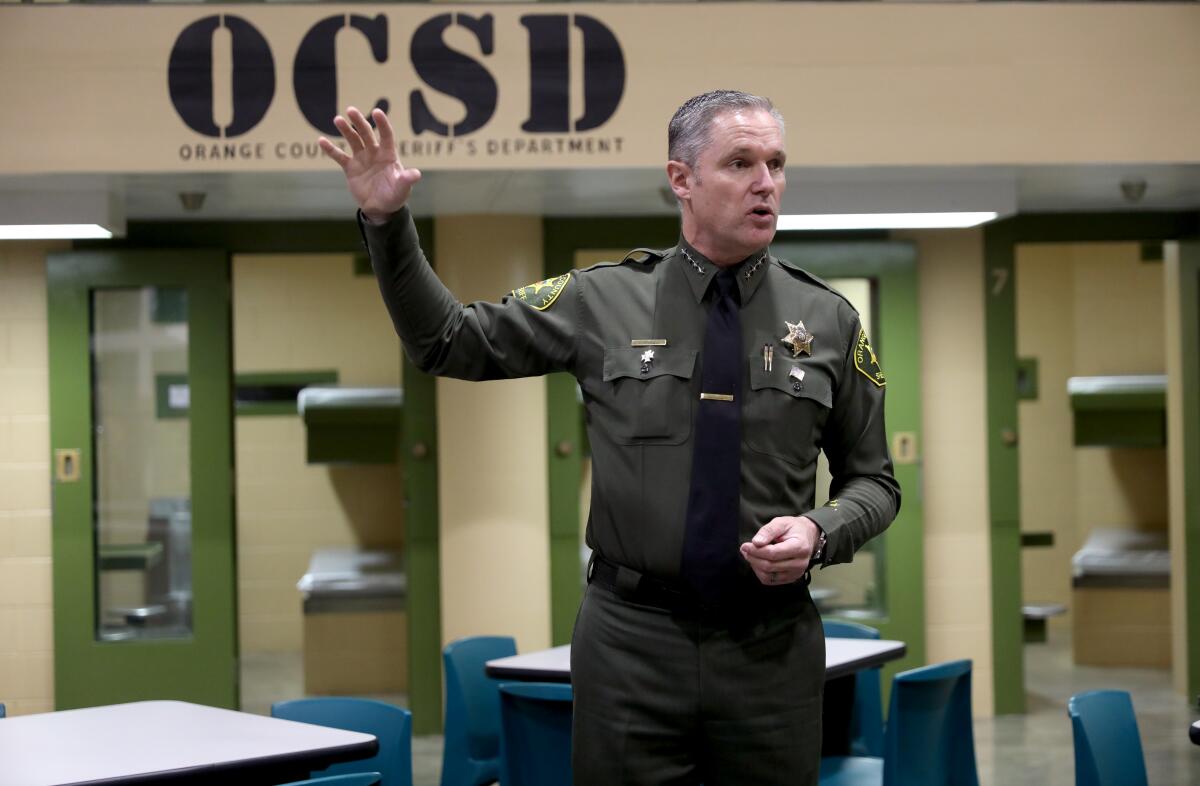

Sheriff Don Barnes said last week that the Sheriff’s Department identified issues with evidence booking, investigated it and held people accountable when it was necessary. He said that while he was “tremendously disappointed” in the individuals who were identified during the probe, he added that “the purpose of discipline is not to permanently banish somebody.”

“In fact, by law, I cannot separate out or treat somebody differently because of discipline,” he said. “Discipline is intended to correct behavior, and once that discipline is imposed and served, they come back to the organization with the expectation that they will be a contributing member of the Sheriff’s Department ....”

The department’s booking protocol requires deputies to enter evidence information in a computer database and then tag and place the evidence in a secure locker.

In 2018, the Sheriff’s Department submitted information on 15 deputies — including Avalos — who were identified as having mishandled evidence to the Orange County district attorney’s office for possible criminal charges. The office initially declined to prosecute any of the deputies.

The Sheriff’s Department then conducted an internal affairs investigation, which resulted in the termination of five deputies. Nine more faced disciplinary measures, which included forcing them to take unpaid hours off.

Dist. Atty. Todd Spitzer has since reopened the criminal investigations in conjunction with sheriff’s officials. Spitzer said he was not aware of the scope of the issue given that each of the cases was submitted to his office individually rather than all at once.

“It is entirely inappropriate for your staff to publicly assert that my office had knowledge of the existence of a department-wide audit when we clearly did not,” Spitzer wrote in a letter to Barnes last year.

“To insert a single line in your submissions to the effect as a result of an audit did not in any way address the department-wide review in which your department was actually engaged. There was no effort by your department to put these cases in context.”

Two more deputies have been accused of wrongdoing since the new probe was opened.

Avalos’ booking practices, according to Sanders, “were among the worst in the agency.” Avalos’ average delay in booking evidence in his cases was nine times that of a typical deputy in the department, according to the filing. It took Avalos on average 30.6 days to book evidence, which is 27.2 days longer than the department’s average of 3.4 days.

Sanders also raised questions about how Avalos kept track of methamphetamine, heroin and cocaine that he seized in various cases. He contends that Avalos kept collected items “mixed together in a desk stuffed with evidence from other cases.”

In response to the internal affairs probe, the department placed Avalos on unpaid leave for 60 hours. He was promoted to sergeant last year and moved from the investigations division to the men’s central jail, according to court records.

Avalos could not be reached for comment. But during an interview in 2018, Avalos described his booking procedure as “bad habits.”

“Deputy Avalos explained that he now realizes that what he was doing was not the best practice. His routine or personal procedure for booking evidence was in an effort to spend less time in the office and more time helping his partners or search for criminal activity. This practice eventually led to poor endings to cases,” the sheriff’s investigator wrote in a report.

Avalos told the investigator that he was disappointed and his behavior did not reflect “how he wants to portray himself.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.